SFRA Newsletter, 183, December 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

SF Commentary 41-42

S F COMMENTARY 41/42 Brian De Palma (dir): GET TO KNOW YOUR RABBIT Bruce Gillespie: I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (86) . ■ (SFC 40) (96) Philip Dick (13, -18-19, 37, 45, 66, 80-82, 89- Bruce Gillespie (ed): S F COMMENTARY 30/31 (81, 91, 96-98) 95) Philip Dick: AUTOFAC (15) Dian Girard: EAT, DRINK AND BE MERRY (64) Philip Dick: FLOW MY TEARS THE POLICEMAN SAID Victor Gollancz Ltd (9-11, 73) (18-19) Paul Goodman (14). Gordon Dickson: THINGS WHICH ARE CAESAR'S (87) Giles Gordon (9) Thomas Disch (18, 54, 71, 81) John Gordon (75) Thomas Disch: EMANCIPATION (96) Betsey & David Gorman (95) Thomas Disch: THE RIGHT WAY TO FIGURE PLUMBING Granada Publishing (8) (7-8, 11) Gunter Grass: THE TIN DRUM (46) Thomas Disch: 334 (61-64, 71, 74) Thomas Gray: ELEGY WRITTEN IN A COUNTRY CHURCH Thomas Disch: THINGS LOST (87) YARD (19) Thomas Disch: A VACATION ON EARTH (8) Gene Hackman (86) Anatoliy Dneprov: THE ISLAND OF CRABS (15) Joe Haldeman: HERO (87) Stanley Donen (dir): SINGING IN THE RAIN (84- Joe Haldeman: POWER COMPLEX (87) 85) Knut Hamsun: MYSTERIES (83) John Donne (78) Carey Handfield (3, 8) Gardner Dozois: THE LAST DAY OF JULY (89) Lee Harding: FALLEN SPACEMAN (11) Gardner Dozois: A SPECIAL KIND OF MORNING (95- Lee Harding (ed): SPACE AGE NEWSLETTER (11) 96) Eric Harries-Harris (7) Eastercon 73 (47-54, 57-60, 82) Harry Harrison: BY THE FALLS (8) EAST LYNNE (80) Harry Harrison: MAKE ROOM! MAKE ROOM! (62) Heinz Edelman & George Dunning (dirs): YELLOW Harry Harrison: ONE STEP FROM EARTH (11) SUBMARINE (85) Harry Harrison & Brian Aldiss (eds): THE -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

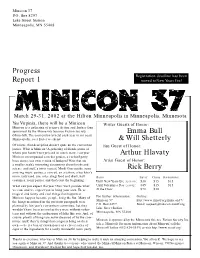

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

Science Fiction Review 54

SCIENCE FICTION SPRING T)T7"\ / | IjlTIT NUMBER 54 1985 XXEj V J. JL VV $2.50 interview L. NEIL SMITH ALEXIS GILLILAND DAMON KNIGHT HANNAH SHAPERO DARRELL SCHWEITZER GENEDEWEESE ELTON ELLIOTT RICHARD FOSTE: GEIS BRAD SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 FEBRUARY, 1985 - VOL. 14, NO. 1 PHONE (503) 282-0381 WHOLE NUMBER 54 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher ALIEN THOUGHTS.A PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR BY RICHARD E. GE1S ALIEN THOUGHTS.4 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY RICHARD E, GEIS FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. interview: L. NEIL SMITH.8 SINGLE COPY - $2.50 CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS THE VIVISECT0R.50 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER NOISE LEVEL.16 A COLUMN BY JOUV BRUNNER NOT NECESSARILY REVIEWS.54 SUBSCRIPTIONS BY RICHARD E. GEIS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ONCE OVER LIGHTLY.18 P.O. BOX 11408 BOOK REVIEWS BY GENE DEWEESE LETTERS I NEVER ANSWERED.57 PORTLAND, OR 97211 BY DAMON KNIGHT LETTERS.20 FOR ONE YEAR AND FOR MAXIMUM 7-ISSUE FORREST J. ACKERMAN SUBSCRIPTIONS AT FOUR-ISSUES-PER- TEN YEARS AGO IN SF- YEAR SCHEDULE. FINAL ISSUE: IYOV■186. BUZZ DIXON WINTER, 1974.57 BUZ BUSBY BY ROBERT SABELLA UNITED STATES: $9.00 One Year DARRELL SCHWEITZER $15.75 Seven Issues KERRY E. DAVIS SMALL PRESS NOTES.58 RONALD L, LAMBERT BY RICHARD E. GEIS ALL FOREIGN: US$9.50 One Year ALAN DEAN FOSTER US$15.75 Seven Issues PETER PINTO RAISING HACKLES.60 NEAL WILGUS BY ELTON T. ELLIOTT All foreign subscriptions must be ROBERT A.Wi LOWNDES paid in US$ cheques or money orders, ROBERT BLOCH except to designated agents below: GENE WOLFE UK: Wm. -

Agenda Settimanale Degli Eventi Al Cinema Massimo

Agenda settimanale degli eventi al Cinema Massimo da venerdì 4 maggio a giovedì 10 maggio 2012 Cinema Massimo - via Verdi 18, Torino Sommario: 05.05 – I CARTONI ANIMATI DELLA WARNER BROS .– Il meglio di Bugs Bunny (ore 15.00) 06.05 – I CARTONI ANIMATI DELLA WARNER BROS .– Il meglio di Beep Beep & Wile E.Coyote (ore15.00) 08.05 – MAGNIFICHE VISIONI – Lo strangolatore di Boston di Richard Fleischer (ore 20.45) 09.05 – CULT! - Rolling Thunder di John Flynn (20.30/22.15) -SABATO 5 MAGGIO e DOMENICA 6 MAGGIO, ORE 15.00 – SALA TRE In occasione della mostra Bugs, Daffy, Silvestro & Co. I cartoni animati della Warner Bros. il Museo Nazionale del Cinema presenta al Cinema Massimo Il meglio di Bugs Bunny e Il meglio di Beep Beep & Wile E. Coyote. Visto il grande successo di pubblico ottenuto dalle proiezioni del week-end dedicate ai personaggi animati del mondo Warner, il Museo Nazionale del Cinema propone, anche per il mese di maggio, una divertente incursione nell’universo dei Looney Tunes. Sabato 5 e domenica 6 maggio , alle ore 15.00 , verranno replicati, nella Sala Tre del Cinema Massimo, Il meglio di Bugs Bunny e Il meglio di Beep Beep & Wile E. Coyote , una selezione delle migliori storie dei personaggi più popolari della serie. Proiettata nei cinema dal 1930 al 1969, Looney Tunes (melodie pazzerelle) è la prima serie animata della Warner Bros nonché la seconda più lunga mai trasmessa. Bugs Bunny - la lepre “nata” nel 1938 a Brooklyn da molti padri - ne è uno dei protagonisti più famosi. Ottenuto il primo posto della classifica dei 50 più grandi personaggi animati di tutti i tempi redatta dalla rivista TVGuide nel 2002, Bugs Bunny è un equivalente moderno della figura mitologica dell’imbroglione. -

Thri-Kreen of Athas

Official Game Accessory Tkri-Kreen of Athas by Tim Beach and Don Hein Credits Sourceboolc Design: Tim Beach Adventure Design: Don Jean Hein Editing: Jon Pickens Cover Art: Ned Dameron Interior Art: John Dollar Art Coordination: Peggy Cooper Graphics Coordination: Sarah Feggestad CartographySample: Diese filel Typography: Angelika Lokotz Thank T(ou: Tom FVusa, Kari Landsverk, Wolfgang Baur, Bill Slavicsek, Rich Baker, Kim Baker, Michele Carter, William W Connors, Colin McComb, Skip Williams, Lisa Smedman, Andria Hayday, Tim Brown, and Bruce Heard. TSR, Inc. TSR Ltd. 201 Sheridan Springs Rd. 120 Church End Lake Geneva Cherry Hinton WI53147 Cambridge CB13LB U.SA United Kingdom 2437 ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, AD&D, DUNGEON MASTER, DARK SUN, GREYHAWK, FORGOTTEN REALMS, DRAGONLANCE, SPELUAMMER, RAVENLOFT, ALQADIM, DRAGONS CROWN, and MONSTROUS COMPENDIUM are registered trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. PLANESCAPE, MONSTROUS MANUAL, RED STEEL, MYSTARA, DM, and tke TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. All TSR characters, character names, and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Random House and its affiliate companies have worldwide distribution rights in the book trade for English-language products of TSR, Inc. Distributed to the book and hobby trade in the United Kingdom by TSR Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. This product is protected by the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

DECK the FRIDGE with SHEETS of EINBLATT, FA LA LA LA LA JANUARY 1991 DEC 29 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 Pm On, at Home of Herm

DECK THE FRIDGE WITH SHEETS OF EINBLATT, FA LA LA LA LA JANUARY 1991 DEC 29 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 pm on, at home of Herman Schouten and Gerri Balter and more than one stuffed animal / 1381 N. Pascal Street (St. Paul). No smoking; house is not childproofed. FFI: 646-3852. DEC 31 (Mon): New Year's Eve party. 3:30 pm until next year, at home of Jerry Corwin and Julie Johnson / 3040 Grand Avenue S. (Mpls). Cats; no smoking; house is not childproofed. FFI: 824-7800. JAN 1 (Tue): New Year's Day Open House. 2 to 9 pm, at home of Carol Kennedy and Jonathan Adams / 3336 Aldrich Avenue S. (Mpls). House is described as "child-proofed, more or less." Cats. No smoking. FFI: 823-2784. 5 (Sat): Stipple-Apa 88 collation. 2 pm, at home of Joyce Maetta Odum / 2929 32nd Avenue S. (Mpls). Copy count is 32. House is childproofed. No smoking. FFI: 729-6577 (Maetta) or 331-3655 (Stipple OK Peter). 6 (Sun): Ladies' Sewing Circle and Terrorist Society. 2 pm on, at home of Jane Strauss / 3120 3rd Avenue S. (Mpls). Childproofed. FFI: 827-6706. 12 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 pm on, at home of Marianne Hageman and Mike Dorn / 2965 Payne Avenue (Little Canada). No smoking. Not childproofed. "Believable numbers of huggable stuffed animals." FFI: 483-3422. 12 (Sat): Minneapa 261 collation. 2 pm, at the Minn-STF Meeting. Copy count is 30. Believable numbers of apahacks. FFI: OE Dean Gahlon at 827-1775. 12 (Sat): World Building Group of MIFWA meets at 1 pm at Apache Wells Saloon / Apache Plaza / 37th Avenue and Silver Lake Road (St. -

0 OPĆENITO 001 ZNANOST I ZNANJE OPĆENITO 001 CORSO Dan CORSO, Philip J

POINT Software Varaždin Str. 1 0 OPĆENITO 001 ZNANOST I ZNANJE OPĆENITO 001 CORSO dan CORSO, Philip J. 001 Dan poslije Roswella / Philip J. Corso u suradnji Williama J. Birnesa ; s engleskog preveo Predrag Raos. - Zagreb : AGM, 2010. - 443 str. : ilustr. ; 22 cm. - (Biblioteka Obelisk : koja razotkriva svijet zagonetnih sila i rubnih područja ljudskog znanja) znanja) Prijevod djela : The day after Roswell. ISBN 978-953-174-374-7 Prema Corsu, temelj američke politike prema NLO-ima udaren je ubrzo nakon pada NLO-a kraj Roswella. U konfuznim satima nakon otkrića srušene letjelice vojska je odlučila da, u nedostatku drugačijih informacija, smatra da je riječ o izvanzemaljskoj letjelici. Te su letjelice nadgledale vojne instalacije tehnologijom za koju su već znali da su s njom bili upoznati i nacisti, što je potaknulo vojsku da pretpostavi da imaju neprijateljske namjere i da su interferirali sa ljudima tijekom rata. Nije se znalo što su htjela bića u letjelicama, ali su iz njihova ponašanja, kao što su intervencije u ljudske živote ('otmice') i sakaćenje stoke, zaključili da su potencijalni neprijatelji. 001 FORBE mac FORBES, Peter 001 Macaklinovo stopalo / Peter Forbes ; s engleskoga prevela Snježana Ercegovac. - Zagreb : Profil multimedija, 2010. - 362 str. ; 21 cm. - (Biblioteka Indigo) Prijevod djela: Gecko's foot. ISBN 978-953-319-013-6 Ovo je knjiga o suvremenim znanstvenicima koji proučavanjem prirode nastoje iskoristiti njezina načela i izume te ih primijeniti u svakodnevnom ljudskom životu, ovo je knjiga o nanotehnologiji. 001 GJURI kru GJURINEK, Stjepan 001 Krugovi nove budućnosti / Stjepan Gjurinek. - Zagreb : AGM, 2010. - 166 str. ; 22 cm. - (Biblioteka Obelisk : koja razotkriva svijet zagonetnih sila i rubnih područja ljudskoga znanja) znanja) ISBN 978-953-174-376-1 Piktogrami u usjevima jedan su od najvećih misterija današnjice, koji se uporno opiru brojnim pokušajima njihova objašnjenja, kako onima znanstvene naravi, tako i onim egzotičnijima. -

1566563531375.Pdf

Introduction In the year 1954, the United States government performed 6 nuclear weapons tests in and around the Pacific Ocean. However, this is just the official story. The truth of the matter is that the U.S. Government and Monarch, a multinational, cryptozoological research organization, were trying to kill an ancient and terrifying apex predator. A Titan. This titans name is Titanus Gojira, more recognizably called Gojira or Godzilla. Godzilla’s species ruled the Earth hundreds of millions of years ago, when radiation levels on the planet were astronomically higher. The advent and testing of nuclear weapons awoke Godzilla from his hibernation on the bottom of Earth’s sea floor, where he was feeding off of the planets geothermal radiation. Despite being the first titan to awake, Godzilla is not the only titan that exists on Earth. There are countless others that still sleep or dwell in hidden areas around the world. You begin your stay within this world in 2014, just a scant few weeks before Joe and Ford Brody witness the awakening of the titan known as the MUTO. A scant few weeks before Godzilla becomes known to the world. Location San Francisco, California (1) San Francisco is a massive American metropolis with an area of about 231 square miles. It is bustling with a population nearing one million and holds some of America’s most iconic landmarks. However, this could all change very quickly in the coming years. This city will become the site of an incredible battle between Godzilla and the two MUTO in the year 2014, which will cause severe damage to the city as a whole.