The (Ir)Relevance of Science Fiction to Non-Binary and Genderqueer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

![N38wr [Read Now] Oceanic (English Edition) Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6953/n38wr-read-now-oceanic-english-edition-online-296953.webp)

N38wr [Read Now] Oceanic (English Edition) Online

n38wr [Read now] Oceanic (English Edition) Online [n38wr.ebook] Oceanic (English Edition) Pdf Free Par Greg Egan audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #280493 dans eBooksPublié le: 2009-09-24Sorti le: 2009-09- 24Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 50.Mb Par Greg Egan : Oceanic (English Edition) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Oceanic (English Edition): Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Sci-Fi genre to explore human psychologyPar jmbfrIt may not be usual for Mr. Egan, but this book is less about hard science- fiction than the exploration of the human psychology and emotions.I was surprised by Oceanic but it turned out to express much of my inner thoughts about religion and faith.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. De la SF moderne!Par ALEXANDREDe la SF moderne, qui part de l'état connu de la science et qui extrapole.C'est puissant, riche, philosophique, très bien écrit...Un auteur à découvrir! Présentation de l'éditeurCollected together here for the first time are twelve stories by the incomparable Greg Egan, one of the most exciting writers of science fiction working today.In these dozen glimpses into the future Egan continues to explore the essence of what it is to be human, and the nature of what - and who - we are, in stories that range from parables of contemporary human conflict -

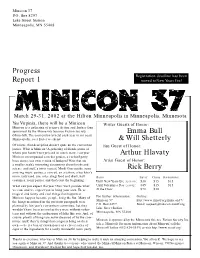

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

Merging with AI Would Be Suicide for the Human Mind

Opinion Artificial intelligence Merging with AI would be suicide for the human mind There may come a moment when the brain is so diminished it is destroyed Your mind is not a back-up drive for AI, even if it has the same memories and exact behaviours © Getty Susan Schneider 54 MINUTES AGO The idea that human and artificial intelligence should merge is in the air these days. The Tesla and SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk, for instance, suggests “having some sort of merger of biological intelligence and machine intelligence”. His company, Neuralink, aims to make implanting chips in the brain as commonplace as laser eye surgery. Underlying all this talk is a radical vision of the mind’s future. Ray Kurzweil, the futurist and director of engineering at Google, envisions a technotopia where human minds upload to the Cloud, becoming hyperconscious, immortal superintelligences. Mr Musk believes people should merge with AI to avoid losing control of superintelligent machines, and prevent technological unemployment. But are such ideas really possible? The philosophical obstacles are as pressing as the technological ones. Here is a new challenge, derived from a story by the Australian science fiction writer Greg Egan. Imagine that an AI device called “a jewel” is inserted into your brain at birth. The jewel monitors your brain’s activity in order to learn how to mimic your thoughts and behaviours. By the time you are an adult, it perfectly simulates your biological brain. At some point, like other members of society, you grow confident that your brain is just redundant meatware. -

DECK the FRIDGE with SHEETS of EINBLATT, FA LA LA LA LA JANUARY 1991 DEC 29 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 Pm On, at Home of Herm

DECK THE FRIDGE WITH SHEETS OF EINBLATT, FA LA LA LA LA JANUARY 1991 DEC 29 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 pm on, at home of Herman Schouten and Gerri Balter and more than one stuffed animal / 1381 N. Pascal Street (St. Paul). No smoking; house is not childproofed. FFI: 646-3852. DEC 31 (Mon): New Year's Eve party. 3:30 pm until next year, at home of Jerry Corwin and Julie Johnson / 3040 Grand Avenue S. (Mpls). Cats; no smoking; house is not childproofed. FFI: 824-7800. JAN 1 (Tue): New Year's Day Open House. 2 to 9 pm, at home of Carol Kennedy and Jonathan Adams / 3336 Aldrich Avenue S. (Mpls). House is described as "child-proofed, more or less." Cats. No smoking. FFI: 823-2784. 5 (Sat): Stipple-Apa 88 collation. 2 pm, at home of Joyce Maetta Odum / 2929 32nd Avenue S. (Mpls). Copy count is 32. House is childproofed. No smoking. FFI: 729-6577 (Maetta) or 331-3655 (Stipple OK Peter). 6 (Sun): Ladies' Sewing Circle and Terrorist Society. 2 pm on, at home of Jane Strauss / 3120 3rd Avenue S. (Mpls). Childproofed. FFI: 827-6706. 12 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 pm on, at home of Marianne Hageman and Mike Dorn / 2965 Payne Avenue (Little Canada). No smoking. Not childproofed. "Believable numbers of huggable stuffed animals." FFI: 483-3422. 12 (Sat): Minneapa 261 collation. 2 pm, at the Minn-STF Meeting. Copy count is 30. Believable numbers of apahacks. FFI: OE Dean Gahlon at 827-1775. 12 (Sat): World Building Group of MIFWA meets at 1 pm at Apache Wells Saloon / Apache Plaza / 37th Avenue and Silver Lake Road (St. -

Nominations�1

Section of the WSFS Constitution says The complete numerical vote totals including all preliminary tallies for rst second places shall b e made public by the Worldcon Committee within ninety days after the Worldcon During the same p erio d the nomination voting totals shall also b e published including in each category the vote counts for at least the fteen highest votegetters and any other candidate receiving a numb er of votes equal to at least ve p ercent of the nomination ballots cast in that category The Hugo Administrator reports There were valid nominating ballots and invalid nominating ballots There were nal ballots received of which were valid Most of the invalid nal ballots were electronic ballots with errors in voting which were corrected by later resubmission by the memb ers only the last received ballot for each memb er was counted Best Novel 382 nominating ballots cast 65 Brasyl by Ian McDonald 58 The Yiddish Policemens Union by Michael Chab on 58 Rol lback by Rob ert J Sawyer 41 The Last Colony by John Scalzi 40 Halting State by Charles Stross 30 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal lows by J K Rowling 29 Making Money by Terry Pratchett 29 Axis by Rob ert Charles Wilson 26 Queen of Candesce Book Two of Virga by Karl Schro eder 25 Accidental Time Machine by Jo e Haldeman 25 Mainspring by Jay Lake 25 Hapenny by Jo Walton 21 Ragamun by Tobias Buckell 20 The Prefect by Alastair Reynolds 19 The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss Best Novella 220 nominating ballots cast 52 Memorare by Gene Wolfe 50 Recovering Ap ollo -

Philosophers' Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction

Philosophers’ Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction Recommendations, Organized by Author / Director November 3, 2014 Eric Schwitzgebel In September and October, 2014, I gathered recommendations of “philosophically interesting” science fiction – or “speculative fiction” (SF), more broadly construed – from thirty-four professional philosophers and from two prominent SF authors with graduate training in philosophy. Each contributor recommended ten works of speculative fiction and wrote a brief “pitch” gesturing toward the interest of the work. Below is the list of recommendations, arranged to highlight the authors and film directors or TV shows who were most often recommended by the list contributors. I have divided the list into (A.) novels, short stories, and other printed media, vs (B.) movies, TV shows, and other non- printed media. Within each category, works are listed by author or director/show, in order of how many different contributors recommended that author or director, and then by chronological order of works for authors and directors/shows with multiple listed works. For works recommended more than once, I have included each contributor’s pitch on a separate line. The most recommended authors were: Recommended by 11 contributors: Ursula K. Le Guin Recommended by 8: Philip K. Dick Recommended by 7: Ted Chiang Greg Egan Recommended by 5: Isaac Asimov Robert A. Heinlein China Miéville Charles Stross Recommended by 4: Jorge Luis Borges Ray Bradbury P. D. James Neal Stephenson Recommended by 3: Edwin Abbott Douglas Adams Margaret -

SF Commentarycommentary 80A80A

SFSF CommentaryCommentary 80A80A August 2010 SSCCAANNNNEERRSS 11999900––22000022 Doug Barbour Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Bruce Gillespie Paul Ewins Alan Stewart SF Commentary 80A August 2010 118 pages Scanners 1990–2002 Edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia as a supplement to SF Commentary 80, The 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 1, also published in August 2010. Email: [email protected] Available only as a PDF from Bill Burns’s site eFanzines.com. Download from http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC80A.pdf This is an orphan issue, comprising the four ‘Scanners’ columns that were not included in SF Commentary 77, then had to be deleted at the last moment from each of SFCs 78 and 79. Interested readers can find the fifth ‘Scanners’ column, by Colin Steele, in SF Commentary 77 (also downloadable from eFanzines.com). Colin Steele’s column returns in SF Commentary 81. This is the only issue of SF Commentary that will not also be published in a print edition. Those who want print copies of SF Commentary Nos 80, 81 and 82 (the combined 40th Anniversary Edition), should send money ($50, by cheque from Australia or by folding money from overseas), traded fanzines, letters of comment or written or artistic contributions. Thanks to Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) for providing the cover at short notice, as well as his explanatory notes. 2 CONTENTS 5 Ditmar: Dick Jenssen: ‘Alien’: the cover graphic Scanners Books written or edited by the following authors are reviewed by: 7 Bruce Gillespie David Lake :: Macdonald Daly :: Stephen Baxter :: Ian McDonald :: A. -

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction By Kym Michelle Brindle Thesis submitted in fulfilment for the degree of PhD in English Literature Department of English and Creative Writing Lancaster University September 2010 ProQuest Number: 11003475 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003475 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis examines the significance of a ubiquitous presence of fictional letters and diaries in neo-Victorian fiction. It investigates how intercalated documents fashion pastiche narrative structures to organise conflicting viewpoints invoked in diaries, letters, and other addressed accounts as epistolary forms. This study concentrates on the strategic ways that writers put fragmented and found material traces in order to emphasise such traces of the past as fragmentary, incomplete, and contradictory. Interpolated documents evoke ideas of privacy, confession, secrecy, sincerity, and seduction only to be exploited and subverted as writers idiosyncratically manipulate epistolary devices to support metacritical agendas. Underpinning this thesis is the premise that much literary neo-Victorian fiction is bound in an incestuous relationship with Victorian studies. -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

U ILLI N I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science Books make great gifts, but pick- ing the perfect books for your favorite youngsters can be daunt- ing. Let the expert staff of The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books help you navigate the book- store wilderness full of shiny new children's books. Updated and expanded from last year's edi- tion, the Guide Book to Gift Books contains annotations for over 225 of the best books for giving (and receiving) and is available as a downloadable PDF file that you can print out and use for every holiday, birthday, or other gift-giving occasion on your calendar this year. Listed books have all been recommended in full Bulletin reviews from the last three years and are verified as currently in print. Entries are divided into age groups and include au- thor, title, publisher, and the current list price. To purchase, go to: www.lis.uiuc.edu/giftbooks/ THE BUvL LE T IN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS January 2004 Vol. 57 No. 5 A LOOK INSIDE 177 THE BIG PICTURE Luba: The Angel ofBergen-Belsen by Luba Tryszynska-Frederick; as told to Michelle R. McCann; illus. by Ann Marshall 178 NEW BOOKS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE Reviewed titles include: 184 *Prep byJake Coburn 191 * September 11, 2001: Attack on New York City by Wilborn Hampton 199 * The Beast by Walter Dean Myers 200 * Thunder Rose by Jerdine Nolen; illus. -

From Water Margins to Borderlands: Boundaries and the Fantastic in Fantasy, Native American, and Asian American Literatures

From Water Margins to Borderlands: Boundaries and the Fantastic in Fantasy, Native American, and Asian American Literatures A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota By Jennifer L. Miller In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David Treuer December 2009 © Jennifer L. Miller 2009 Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. In particular, I would like to thank the following people for their unfailing advice, support, and love: Dr. David Treuer, my advisor, for giving my project a home and for your enthusiasm for my idea. My committee members, Dr. Josephine Lee, Dr. Jack Zipes, and Dr. Qadri Ismail, for their comments, critiques, and advice. I appreciate your willingness to work with a project that exists in between categories, and for pushing your own boundaries to embrace it. The Asian American Studies dissertation writing group, headed by Dr. Josephine Lee. Thank you for including my project in your group. Your support, comments, and advice were extremely helpful, and being part of this group helped provide the impetus for seeing my project through to completion. Kathleen Howard and Lindsay Craig, for your work with me on the Fantasy Matters conference in November of 2007. Thank you for helping me organize a wonderful conference, and for being wonderful friends who helped me figure out my dissertation, academia, and life in general. My parents, Mark Ilten and the late Donna (Sieck) Ilten, for providing me with an incredible literary foundation.