Chronology of Key Titles in Science Fiction and Developments in Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decades of Science Fiction Quarter 4 – 2016 – Reading & Assignment Schedule Read Each Story with the Class And/Or on Your Own

Decades of Science Fiction Quarter 4 – 2016 – Reading & Assignment Schedule Read each story with the class and/or on your own. Write or type your short answers to the five Discussion Questions you will find at the end of each story. These are thoughtful, interpretive questions, so your answers will be original and unique. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ March 30: “The Disintegration Machine” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, pages 65-75 Due April 1 Doyle is the creator of the character Sherlock Holmes. Respond to Discussion Questions 1 through 5 on pages 75 & 76. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ April 1: “The Metal Man” by Jack Williamson, pages 78-87 Due April 5 Answer all five Discussion Questions on page 87. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ April 5: “Misfit” by Robert Heinlein, pages 119-137 Due April 7 Robert Heinlein is perhaps most well-known for his 1959 novel Starship Troopers. “Misfit” is also military science fiction. Discussion Questions 1 through 5 are on page 137. Answer them all. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ April 7: “Robbie” by Isaac Asimov, pages 149-165 Due April 11 “Robbie” is one of Asimov’s collected stories in I, Robot. Asimov created the “Three Laws of Robotics” in his extensive Robot series. “1. A Robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. 2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law. 3. A robot must protect its own existence, except where such protection would conflict with the First or Second Law.” Answer Discussion Questions 1, 2, 3, 4, & 5 on page 165. -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

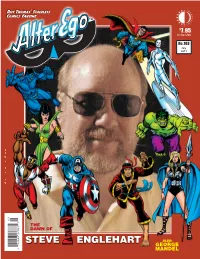

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Review 330 Fall 2019 SFRA

SFRA RREVIEWS, ARTICLES,e ANDview NEWS FROM THE SFRA SINCE 1971 330 Fall 2019 FEATURING Area X: Five Years Later PB • SFRA Review 330 • Fall 2019 Proceedings of the SFRASFRA 2019 Review 330Conference • Fall 2019 • 1 330 THE OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF THE Fall 2019 SFRA MASTHEAD ReSCIENCE FICTIONview RESEARCH ASSOCIATION SENIOR EDITORS ISSN 2641-2837 EDITOR SFRA Review is an open access journal published four times a year by Sean Guynes Michigan State University the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA) since 1971. SFRA [email protected] Review publishes scholarly articles and reviews. The Review is devoted to surveying the contemporary field of SF scholarship, fiction, and MANAGING EDITOR media as it develops. Ian Campbell Georgia State University [email protected] Submissions ASSOCIATE EDITOR SFRA Review accepts original scholarly articles; interviews; Virginia Conn review essays; individual reviews of recent scholarship, fiction, Rutgers University and media germane to SF studies. [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR All submissions should be prepared in MLA 8th ed. style and Amandine Faucheux submitted to the appropriate editor for consideration. Accepted University of Louisiana at Lafayette pieces are published at the discretion of the editors under the [email protected] author's copyright and made available open access via a CC-BY- NC-ND 4.0 license. REVIEWS EDITORS NONFICTION EDITOR SFRA Review does not accept unsolicited reviews. If you would like Dominick Grace to write a review essay or review, please contact the appropriate Brescia University College [email protected] review editor. For all other publication types—including special issues and symposia—contact the editor, managing, and/or ASSISTANT NONFICTION EDITOR associate editors. -

Astronomy and Astronomers in Jules Verne's Novels

The Rˆole of Astronomy in Society and Culture Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 260, 2009 c 2009 International Astronomical Union D. Valls-Gabaud & A. Boksenberg, eds. DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X Astronomy and astronomers in Jules Verne’s novels Jacques Crovisier Observatoire de Paris, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France email: [email protected] Abstract. Almost all the Voyages Extraordinaires written by Jules Verne refer to astronomy. In some of them, astronomy is even the leading theme. However, Jules Verne was basically not learned in science. His knowledge of astronomy came from contemporaneous popular publications and discussions with specialists among his friends or his family. In this article, I examine, from the text and illustrations of his novels, how astronomy was perceived and conveyed by Jules Verne, with errors and limitations on the one hand, with great respect and enthusiasm on the other hand. This informs us on how astronomy was understood by an “honnˆete homme” in the late 19th century. Keywords. Verne J., literature, 19th century 1. Introduction Jules Verne (1828–1905) wrote more than 60 novels which constitute the Voyages Extraordinaires series†. Most of them were scientific novels, announcing modern science fiction. However, following the strong suggestions of his editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel, Jules Verne promoted science in his novels, so that they could be sold as educational material to the youth (Fig. 1). Jules Verne had no scientific education. He relied on popular publications and discussions with specialists chosen among friends and relatives. This article briefly presents several examples of how astronomy appears in the text and illustrations of the Voyages Extraordinaires. -

Holiday Reading 2001

Holiday reading A selection of children’s and young adults’ books 10/01 G CH-128-B This list is only a small selection of the many books added to Christchurch City Libraries during 2001. We hope you will find some to interest you. Previous Holiday Reading lists can be found on the library’s web site at: http://library.christchurch.org.nz/Childrens/HolidayReading/index.asp Some recent award winning books are listed at the end of this publication while more award winners can be found on the library’s web site at: http://library.christchurch.org.nz/Guides/ LiteraryPrizes/Childrens/index.asp In Memoriam: Christchurch writers & illustrators Elsie Locke Gwenda Turner Douglas Adams Betty Cavanna Mirra Ginsberg Adrian Henri Tove Jannson Eloise McGraw Fred Marcellino Robert Kraus Catherine Storr This edition of Holiday Reading is dedicated to Alf Baker, a long-time supporter of children’s literature, literacy and libraries, who died during the year. Holiday reading page 1 Picture books Agee, Jon Milo’s hat trick In the busy city there are lots of people with hats, but only Milo the magician has a bear in his hat. Ahlberg, Allan The adventures of Bert Three very short stories, illustrated by Raymond Briggs. Ahlberg, Allan The snail house Grandma tells Michael, Hannah and their baby brother the story of three children who shrink to such a small size they move into a snail’s shell. Alborough, Jez Fix-It Duck Duck’s attempts to deal with various minor disasters only lead to more problems. Observant readers will notice in the initial pictures the clue to the first cause of the trouble. -

The Imagined Wests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies

Portland State University PDXScholar Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Publications and Presentations Planning Spring 2003 Falling into History: The Imagined Wests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies Carl Abbott Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Abbott, C. Falling into History: The Imagined Wests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies. The Western Historical Quarterly , Vol. 34, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 27-47. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Falling into History: The ImaginedWests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies Carl Abbott California science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson has imagined the future of Southern California in three novels published 1984-1990, and the settle ment of Mars in another trilogy published 1993-1996. In framing these narratives he worked in explicitly historical terms and incorporated themes and issues that characterize the "new western history" of the 1980s and 1990s, thus providing evidence of the resonance of that new historiography. .EDMars is Kim Stanley Robinson's R highly praised science fiction novel published in 1993.1 Its pivotal section carries the title "Falling into History." More than two decades have passed since permanent human settlers arrived on the red planet in 2027, and the growing Martian communities have become too complex to be guided by simple earth-made plans or single individuals. -

Planets, Comets and Small Bodies in Jules Verne's Novels

DPS-EPSC joint meeting Nantes, 2-7 October 2011 Planets, comets and small bodies in Jules Verne's novels J. Crovisier Observatoire de Paris LESIA, CNRS, UPMC, Université Paris-Diderot 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France Jules Verne Nantes – 8 February 1828 Amiens – 24 March 1905 An original binding of Almost all the Voyages Extraordinaires written by Jules Verne refer to astronomy. In some of From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon them, astronomy is even the leading theme. However, Jules Verne was basically not learned in science. His knowledge of astronomy came from contemporaneous popular publications and discussions with specialists among his friends or his family. Here, we examine, from selected texts and illustrations of his novels, how astronomy — and especially planetary science — was perceived and conveyed by Jules Verne, with errors and limitations on the one hand, with great respect and enthusiasm on the other hand. Jules Verne was born in Nantes, where most of the manuscripts of his novels are now deposited in the municipal library. They were heavily edited by the publishers Pierre-Jules and Louis-Jules Hetzel, by Jules Verne himself, and (for the last ones) by his son Michel Verne. This poster briefly discusses how astronomy appears in the texts and illustrations of the Voyages Extraordinaires, concentrating on several examples among planetary science. More material can be found in the abstract and in the web page : http://www.lesia.obspm.fr/perso/jacques-crovisier/JV/verne_gene_eng.html De la Terre à la Lune (1865, From the Earth to the Moon) and Autour de la Lune (1870, Around Palmyrin Rosette, the free-lance The rival astronomers in The Chase of the Golden Meteor. -

![N38wr [Read Now] Oceanic (English Edition) Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6953/n38wr-read-now-oceanic-english-edition-online-296953.webp)

N38wr [Read Now] Oceanic (English Edition) Online

n38wr [Read now] Oceanic (English Edition) Online [n38wr.ebook] Oceanic (English Edition) Pdf Free Par Greg Egan audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #280493 dans eBooksPublié le: 2009-09-24Sorti le: 2009-09- 24Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 50.Mb Par Greg Egan : Oceanic (English Edition) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Oceanic (English Edition): Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Sci-Fi genre to explore human psychologyPar jmbfrIt may not be usual for Mr. Egan, but this book is less about hard science- fiction than the exploration of the human psychology and emotions.I was surprised by Oceanic but it turned out to express much of my inner thoughts about religion and faith.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. De la SF moderne!Par ALEXANDREDe la SF moderne, qui part de l'état connu de la science et qui extrapole.C'est puissant, riche, philosophique, très bien écrit...Un auteur à découvrir! Présentation de l'éditeurCollected together here for the first time are twelve stories by the incomparable Greg Egan, one of the most exciting writers of science fiction working today.In these dozen glimpses into the future Egan continues to explore the essence of what it is to be human, and the nature of what - and who - we are, in stories that range from parables of contemporary human conflict