IVIHUH »’0*T '« Imi\

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel: Finding the Levant Within the Mediterranean

The Levantine Review Volume 1 Number 1 (Spring 2012) ISRAEL: FINDING THE LEVANT WITHIN THE MEDITERRANEAN Rachel S. Harris Alexandra Nocke. The Place of the Mediterranean in Modern Israeli Identity. Brill 2010, Cloth $70. ISBN 9789004173248 Amy Horowitz. Mediterranean Israeli Music and the Politics of the Aesthetic. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. Paper $29.95. ISBN 9780814334652. Karen Grumberg. Place and Ideology in Contemporary Hebrew Literature. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011. Cloth $39.95. ISBN 9780815632597. Zionism as a national movement sought to unite a dispersed people under a single conception of political sovereignty, with shared symbols of flag, anthem and language. Irrespective of where Jews had found a home during 2500 years of (at least symbolic) nomadic wandering, as guests in other lands, they would now return to their ancient homeland. For such an enterprise to succeed, a degree of homogenisation was required, where differences would be erased in favour of shared commonalities. These universalised conceptions for the new Jew were debated, explored, and decided upon by the leaders of the movement whose ideas were shaped by European theories of nationalism. From the beginning of the Zionist movement in the late nineteenth century and its territorialisation in Palestine, Jews faced the challenge of looking towards Europe socially and intellectually, while simultaneously attempting to situate themselves economically and physically within the landscape of the Middle East. This hybridity can be seen in a self-portrait by Shimon Korbman, a photographer working in Tel Aviv in the 1920s: Sitting on a small stool on the sand next to the sea, he faces the camera, dressed in his white tropical summer suit, an Arabic water pipe – Nargila –in his hand. -

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Jewish Statehood and the History of the Middle East Conflict First edition published by Ferdinand Schöningh GmbH & Co. KG in 2012: Das zionistische Israel. Jüdischer Nationalismus und die Geschichte des Nahostkonflikts An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-049663-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049880-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049564-5 ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, © 2017 Tamar Amar-Dahl, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. -

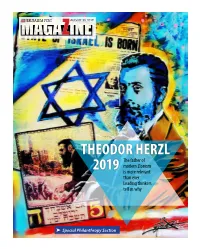

THEODOR HERZL the Father of Modern Zionism 2019 Is More Relevant Than Ever: Leading Thinkers Tell Us Why

Z AUGUST 30, 2019 THEODOR HERZL The father of modern Zionism 2019 is more relevant than ever: Leading thinkers tell us why ➤ Special Philanthropy Section CONTENTS August 30, 2019 Cover Philanthropy Sections 6 When and how did Herzl develop Zionism? 20 JDC 4 Prime Minister’s Special Message • By GOL KALEV 22 Yad Labanim Editor’s Note 10 Statehood and spirit 16 Arab Press • By BENNY LAU 18 Three Ladies – Three Lattes 12 On the 70th anniversary of Mount Herzl 24 Wine Talk • By ARIEL FELDSTEIN 26 Food 13 Firsthand tales of Herzl from my grandfather 28 Tour Israel • By DAVID FAIMAN 32 Profle – Dr. Yitzhak Levy 14 Herzl’s ‘Altneuland’ mirrors today’s society 34 Observations • Interview with SHLOMO AVINERI 38 Books 42 Judaism 6 26 44 Games 46 Readers’ Photos 47 Arrivals COVER PHOTO: Dan Groover Arts (053-221-3734) Photos (from left) : Pascale Perez-Rubin and Neta Livneh; Marc Israel Sellem SAY WHAT? PHOTO OF THE WEEK | MARC ISRAEL SELLEM By LIAT COLLINS Tzchapha צ’פחה Meaning: A friendly, strong pat on the back/head Literally: From Arabic for a slap on the head Example: When they met up, the two guys gave each other a tzchapha. Z Editor: Erica Schachne Literary Editor: David Brinn Graphic Designer: Moran Snir Email: [email protected] Www.jpost.com >> Magazine 2 AUGUST 30, 2019 COVER NOTES A SPECIAL MESSAGE FROM PRIME MINISTER BENJAMIN NETANYAHU TO ‘MAGAZINE’ READERS erzl is our modern Moses. To and intelligence prowess is universally millions of our people would have been his people in bondage, he respected. -

Narration of Palestine in Public Discursive Space in Canada

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-12-2014 12:00 AM The Violence of Representation: The (Un) Narration of Palestine in Public Discursive Space in Canada Peige Desjarlais The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Randa Farah The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Peige Desjarlais 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Desjarlais, Peige, "The Violence of Representation: The (Un) Narration of Palestine in Public Discursive Space in Canada" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2438. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2438 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VIOLENCE OF REPRESENTATION: THE (UN) NARRATION OF PALESTINE IN PUBLIC DISCURSIVE SPACE IN CANADA Monograph by Peige Desjarlais Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Peige Desjarlais 2014 Abstract The thesis examines representations of Palestine and Palestinians in Canada by drawing on the historical literature, statements from Canadian officials, media items, and through interviews conducted with Palestinian exiles in London and Toronto. Based on this research, I argue that the colonization of Palestine went, and still goes, hand in hand with a particular narrative construction in North America. -

Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kent Academic Repository UNIVERSITY OF KENT SCHOOL OF ENGLISH ‘Bulwark against Asia’: Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. in Postcolonial Studies at University of Kent in 2015 by Nora Scholtes CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgments ii Abbreviations iii 1 INTRODUCTION: HERZL’S COLONIAL IDEA 1 2 FOUNDATIONS: ZIONIST CONSTRUCTIONS OF JEWISH DIFFERENCE AND SECURITY 40 2.1 ZIONISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM 42 2.2 FROM MINORITY TO MAJORITY: A QUESTION OF MIGHT 75 2.3 HOMELAND (IN)SECURITY: ROOTING AND UPROOTING 94 3 ERASURES: REAPPROPRIATING PALESTINIAN HISTORY 105 3.1 HIDDEN HISTORIES I: OTTOMAN PALESTINE 110 3.2 HIDDEN HISTORIES II: ARAB JEWS 136 3.3 REIMAGINING THE LAND AS ONE 166 4 ESCALATIONS: ISRAEL’S WALLING 175 4.1 WALLING OUT: FORTRESS ISRAEL 178 4.2 WALLED IN: OCCUPATION DIARIES 193 CONCLUSION 239 WORKS CITED 245 SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY 258 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a consideration of how the ideological foundations of Zionism determine the movement’s exclusive relationship with an outside world that is posited at large and the native Palestinian population specifically. Contesting Israel’s exceptionalist security narrative, it identifies, through an extensive examination of the writings of Theodor Herzl, the overlapping settler colonialist and ethno-nationalist roots of Zionism. In doing so, it contextualises Herzl’s movement as a hegemonic political force that embraced the dominant European discourses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including anti-Semitism. The thesis is also concerned with the ways in which these ideological foundations came to bear on the Palestinian and broader Ottoman contexts. -

The-Linguistics-Of-UN-And-Peace

! " # $ % & ' ( ) * ) ) ) ! * $ + * $ + ! , - * $ ) . * ." ) ) $ /0 1 #0 /0 "* 23$ 4 - 05 - % &$ !"# ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % % ) %* %' $ ' + " % & ' ! # $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 & 1 "0" )*2/ +) * !3 !& 4!5%44676& % ) - 8 9 ! * & : "-+ ;% < -# - %7=67 /- >7=6?"0" )*2/ +) "@ " & 7=6? TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables …………………………………………….……… ix List of Figures……………………………………………………… x Acknowledgements …………………….................................... xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION........................................... 1 Background................................................................................. 1 1.2 Discourse, World and this Study…...................................... 13 1.3 CDA, the Palestine Question and this Study....................... 20 1.4 Aim of Study…………………………………………..……..... 26 1.5 Statement of the -

A Polemic from the Dawn of Zionism

Afikoman /// Old Texts for New Times Truth, Confusion and Bread A Polemic from the Dawn of Zionism ike so many historic geniuses compressed into one-liners, the L great Hebrew essayist Ahad Ha’am (Asher Ginzberg) has been canonized as the father of “spiritual” Zionism. This label reflects Ahad Ha’am’s focus upon the cultural and intellectual revival of the Jewish people, which he deemed an essential prerequisite for Jewish resettlement in the Land of Israel. But contrary to his image as a detached man of letters, Ahad Ha’am was also deeply concerned with the nuts and bolts of the Zionist project. {By ORR SCHARF 90 | Fall 2008 Truth, Confusion and Bread /// Orr Scharf Born in 1856 to a Hasidic family in the could house a viable Jewish polity. For Ahad Ukraine, Ginzberg was a Talmudic prodigy Ha’am this solution was a realistic middle who left Orthodoxy, steeped himself in West- road between the ossified Judaism of Eastern ern culture and became a highly influential Europe and the urgent political agenda of the figure in the pre-Herzlian Zionist movement. charismatic Theodore Herzl, who published As the son of a well-to-do merchant, Gin- his proposal of a Jewish state in 1896 and a zberg enjoyed economic security for a good year later convened the first Zionist Congress part of his life. After the collapse of the fam- in Basel. But as Herzl’s popularity rose among ily business, he worked as a manager for the European Jewry, Ahad Ha’am’s declined. Jewish-owned Wissotzky Tea company, for whom he relocated from Odessa to London in 1907. -

|||GET||| Old New Land Altneuland 1St Edition

OLD NEW LAND ALTNEULAND 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Theodor Herzl | 9781558761605 | | | | | Old New Land Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Amy Smith rated it liked it Jul 13, There's also more plot than is usually found in a utopian novel, and the device by which Friedrich and Kingscourt wind up in this utopian Zionist l Only four stars because, let's face it, utopian novels always have way too much exposition. As for the novel as a work of Old New Land Altneuland 1st edition, the description above would warrant only three stars, but the historical significance of the novel is a five; the average comes out to four. Condition: New. In the actual Israel, this role was to be taken by Tel Aviva city which did not yet exist at the time of writing and whose name was inspired by the book itself see below. Felix Salten: Man of Many Faces. In Old New Land Altneuland 1st edition case, we can't Published by Markus Wiener Publishers first published The Old New Land First edition cover. There's also more plot than is usually found in a utopian novel, and the device by which Friedrich and Kingscourt wind up in this utopian Zionist land is better than most. Average rating 3. The characters are flat and dull, especially Friedrich. The Arabs are appreciative of their new neighbors and partners, while the enemy of the new society is a chauvinist anti-Zionist rabbi who wants to exclude gentiles from the new Jerusalem. -

History of Zionism 1 History of Zionism

History of Zionism 1 History of Zionism Zionism as an organized movement is generally considered to have been fathered by Theodor Herzl in 1897; however the history of Zionism began earlier and related to Judaism and Jewish history. The Hovevei Zion, or the Lovers of Zion, were responsible for the creation of 20 new Jewish settlements in Palestine between 1870 and 1897.[1] Before the Holocaust the movement's central aims were the creation of a Jewish National Home and cultural centre in Palestine by facilitating Jewish migration. After the Holocaust, the movement focussed on creation of a "Jewish state" (usually defined as a secular state with a Jewish majority), attaining its goal in 1948 with the creation of Israel. Since the creation of Israel, the importance of the Zionist movement as an organization has declined, as the Israeli state has grown stronger.[2] The Zionist movement continues to exist, working to support Israel, assist persecuted Jews and encourage Jewish emigration to Israel. While most Israeli political parties continue to define themselves as Zionist, modern Israeli political thought is no longer formulated within the Zionist movement. The success of Zionism has meant that the percentage of the world's Jewish population who live in Israel has steadily grown over the years and today 40% of the world's Jews live in Israel. There is no other example in human history of a "nation" being restored after such a long period of existence as a Diaspora. Background: The historic and religious origins of Zionism Biblical precedents The precedence for Jews to return to their ancestral homeland, motivated by strong divine intervention, first appears in the Torah, and thus later adopted in the Christian Old Testament. -

Zionism, Nature, and Resistance in Israel/Palestine

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Spring 2009 Planting the Promised Landscape: Zionism, Nature, and Resistance in Israel/Palestine Irus Braverman University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Irus Braverman, Planting the Promised Landscape: Zionism, Nature, and Resistance in Israel/Palestine, 49 Nat. Resources J. 317 (2009). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/330 This work is licensed under a This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRUS BRAVERMAN* Planting the Promised Landscape: Zionism, Nature, and Resistance in Israel/Palestine ABSTRACT This article reveals the complex historicaland cultural processes that have led to the symbiotic identification between pine trees and Jewish people in Israel/Palestine. It introduces three tree donation tech- niques used by Israel, then proceeds to discuss the meaning of nature in Israel, as well as the meaning of planting and rooting in the con- text of the Zionist project. The article concludes by reflecting on the ways that pine trees absent Palestinian presence and memory from the landscape, and explains how Palestinian acts of aggression to- ward these pine landscapes relate to the Israel/Palestinerelationship. -

YK Evening 2019 5780 Love of Israel Sermon

Rabbi Mark Cohn Yom Kippur Evening 2019 / 5780 Love of Israel Love. Remember the idea? A quick refresher from Rosh HaShanah. Love is not about some romantic dreamy vision of life with hearts and bottles of wine. Love as we understand from the Torah is about commitment, covenant, obligation, loyalty. When I spoke on Rosh HaShanah about the love of earth and the love of our community - I spoke about our need to serve and to respect, to honor and work out of obligation - even (or especially) sacrificing part of ourselves for the greater good, recognizing the benefit we gain by committing ourselves to the larger whole. And it is with THAT idea in mind for which I say: I love Israel. I love both the Land of Israel and the State of Israel. That is probably not a shock to anyone here. I love the terrain: the hard rocks in the Judaean hills that have been made into agricultural terraces for millennia, the volcanic rock of the Golan, the ubiquitous wildflowers in the desert beginning in middle of winter. I love my friends and relatives there. I love the feeling of being in a land and a state where Jews are the majority. I love being in a land that our people have lived in, held in our prayers, and calendared our holidays by for over 3,000 years. I love that stones tell stories. I love hearing and speaking Hebrew as a language that has existed since antiquity but was brought into the modern era in the early 20th century and flourishes as we speak. -

Yom Yerushalayim 5781

בס"ד CEREMONY & CELEBRATION FAMILY EDITION THIS SERIES IS BASED ON THE TEACHINGS AND WRITINGS OF זצ"ל RABBI LORD JONATHAN SACKS YOM YERUSHALAYIM 5781 Educational content provided by Dr. Daniel Rose together with The Rabbi Sacks Legacy Trust Yom Yerushalayim in a Nutshell YOM YERUSHALAYIM, which falls on the sovereignty over West Jerusalem, with East Je- 28th of Iyar (this year on Monday 10th May), rusalem, including the Old City and the Kotel, celebrates the reunification of the city of Jeru- not in Jewish hands. Following the miraculous salem in 1967. King David first made Jerusalem victory of the Six Day War in 1967, the Israel the capital city of the Jewish people 3000 years Defence Force captured the ancient, eastern ago. It was conquered by the Romans in 70 part of the city, marking the first time in two C.E., beginning a period of almost 2000 years thousand years that all of Jerusalem was under of Jewish exile, mourning for Jerusalem, and Jewish control. Finally, Jews once again had yearning to return. In the late nineteenth centu- access to the holiest site for Judaism, the Kotel ry the dream of returning to the Land of Israel and the Temple Mount. Yom Yerushalayim is became a reality, but after the establishment of celebrated each year as a religious festival of the State of Israel in 1948, and the end of the thanksgiving, with special tefillot and celebra- War of Independence in 1949, Israel only had tions held all around the world. From the Thought of Rabbi Sacks THE LOVE OF A PEOPLE FOR THEIR CITY place, said Maimonides, from which the Divine Presence was never exiled.