Narration of Palestine in Public Discursive Space in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pilgrimage Through the Biblical Lands of Israel & Palestine The

A PILGRIMAGE FOR SALISBURY CATHEDRAL A Pilgrimage through the Biblical Lands of Israel & Palestine Led by The Dean of Salisbury, The Very Revd Nicholas Papadopulos 23rd May - 1st June, 2020 - The official and preferred pilgrimage partner for the Diocese of Jerusalem- www.lightline.org.uk A Pilgrimage through the Biblical Lands of Israel & Palestine I am thrilled to introduce the first pilgrimage to the Holy Land of my time as Dean. I hope that you will be able to join me. I made my first pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 2016. It was a quite overwhelming experience. Since then I have had the privilege of leading two further pilgrimages, and the prospect of returning to Israel and Palestine in 2020 is very exciting. Why? Because if you are able to come then together we will walk the landscape in which Jesus walked. Together we will pray in places where generations of Christians have prayed, and catch a fresh glimpse of our belonging in an innumerable company of faithful men and women drawn by the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. And together we hear the voices of those who live and work, rejoice and grieve in the towns and villages of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories today. In their stories above all we will come face to face with God, who made himself known in Jesus, who is among us as one who suffers, and yet who draws life eternal out of that suffering. It will be, I am confident, an unforgettable opportunity for pilgrims to encounter the living God Nicholas Lightline Pilgrimages support the work of Friends of The Holy Land and a contribution is made on behalf of each and every pilgrim that travels with Lightline Pilgrimages Day 1, Saturday 23rd May We gather at London Heathrow Airport for our morning flight to Tel Aviv. -

The Use of Cartoons in Popular Protests That Focus on Geographic, Social, Economic and Political Issues

European Journal of Geography Volume 4, Issue 1:22-35, 2013 © Association of European Geographers THE USE OF CARTOONS IN POPULAR PROTESTS THAT FOCUS ON GEOGRAPHIC, SOCIAL, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL ISSUES Mary TOTRY Oranim Academic College of Education, Tivon Post 36006, Israel http://friends.oranim.ac.il/, [email protected] Arnon MEDZINI Oranim Academic College of Education, Tivon Post 36006, Israel http://friends.oranim.ac.il/, [email protected] Abstract The comics and related arts (cartoons, graffiti, illustrated posters and signs) have always played an important role in shaping public protests. From the French Revolution to the recent Arab Spring revolutionary wave of demonstrations and protests, these visual means have stood out thanks to their ability to transmit their message quickly, clearly and descriptively. Often these means have enabled the masses to see their social, economic and political reality in a new and critical light. Social, economic and political cartoons are a popular tool of expression in the media. Cartoons appear every day in the newspapers, often adjacent to the editorials. In many cases cartoons are more successful in demonstrating ideas and information than are complex verbal explanations that require a significant investment of time by the writer and the reader as well. Cartoons attract attention and curiosity, can be read and understood quickly and are able to communicate subversive messages camouflaged as jokes that bring a smile to the reader's face. Cartoons become more effective and successful in countries with strict censorship and widespread illiteracy, among them many countries in the Arab world. Cartoonists are in fact journalists who respond to current events and express their opinions clearly and sometimes even scathingly and satirically. -

Israel: Finding the Levant Within the Mediterranean

The Levantine Review Volume 1 Number 1 (Spring 2012) ISRAEL: FINDING THE LEVANT WITHIN THE MEDITERRANEAN Rachel S. Harris Alexandra Nocke. The Place of the Mediterranean in Modern Israeli Identity. Brill 2010, Cloth $70. ISBN 9789004173248 Amy Horowitz. Mediterranean Israeli Music and the Politics of the Aesthetic. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. Paper $29.95. ISBN 9780814334652. Karen Grumberg. Place and Ideology in Contemporary Hebrew Literature. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011. Cloth $39.95. ISBN 9780815632597. Zionism as a national movement sought to unite a dispersed people under a single conception of political sovereignty, with shared symbols of flag, anthem and language. Irrespective of where Jews had found a home during 2500 years of (at least symbolic) nomadic wandering, as guests in other lands, they would now return to their ancient homeland. For such an enterprise to succeed, a degree of homogenisation was required, where differences would be erased in favour of shared commonalities. These universalised conceptions for the new Jew were debated, explored, and decided upon by the leaders of the movement whose ideas were shaped by European theories of nationalism. From the beginning of the Zionist movement in the late nineteenth century and its territorialisation in Palestine, Jews faced the challenge of looking towards Europe socially and intellectually, while simultaneously attempting to situate themselves economically and physically within the landscape of the Middle East. This hybridity can be seen in a self-portrait by Shimon Korbman, a photographer working in Tel Aviv in the 1920s: Sitting on a small stool on the sand next to the sea, he faces the camera, dressed in his white tropical summer suit, an Arabic water pipe – Nargila –in his hand. -

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Jewish Statehood and the History of the Middle East Conflict First edition published by Ferdinand Schöningh GmbH & Co. KG in 2012: Das zionistische Israel. Jüdischer Nationalismus und die Geschichte des Nahostkonflikts An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-049663-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049880-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049564-5 ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, © 2017 Tamar Amar-Dahl, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. -

Palestinian Citizens of Israel: a Perfect Coronavirus Scapegoat

Palestinian citizens of Israel: A perfect coronavirus scapegoat Lana Tatour 8 April 2020 11:36 UTC | Last update: 9 hours 59 min ago As Netanyahu continues racist incitement against Arab citizens, Israeli security forces are unleashing violence on Palestinian communities A mannequin wears a face mask with the pattern of the Palestinian keffiyeh (AFP) 235Shares In a recent meeting about Covid-19 with a delegation of doctors who are Palestinian citizens of Israel, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said: “Unfortunately, instructions are not strictly adhered to in the Arab sector … I ask for the cooperation of all Arab citizens of Israel. I ask you, for your sake and for the sake of our shared future, please follow the orders, [otherwise] a lot of people will die, and these deaths could be prevented with your help.” Clearly, controlling the proliferation of coronavirus depends on the commitment of people to self-isolate, but this is not what Netanyahu meant. Rather, he was continuing his racist incitement against Palestinian citizens, suggesting that deaths would be “your” responsibility. Portrayed as a threat Palestinian citizens are the perfect scapegoat to blame for the spread of Covid-19 in Israel. Palestinian citizens of Israel are being portrayed as a threat to the health and lives of Jewish citizens - a continuation of the longstanding discourse that portrays them as a fifth column and illegitimate citizens. In a discourse that mirrors the classic European antisemitic playbook of “Jews spreading disease”, Netanyahu is preparing the ground to blame Palestinians for the spread of coronavirus if mitigation efforts fail. He is doing what he knows best: inciting against Palestinian citizens to avoid scrutiny over his own handling of the crisis, and to deflect from his pending criminal charges. -

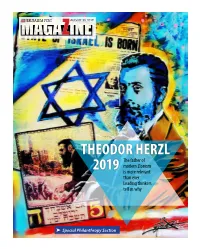

THEODOR HERZL the Father of Modern Zionism 2019 Is More Relevant Than Ever: Leading Thinkers Tell Us Why

Z AUGUST 30, 2019 THEODOR HERZL The father of modern Zionism 2019 is more relevant than ever: Leading thinkers tell us why ➤ Special Philanthropy Section CONTENTS August 30, 2019 Cover Philanthropy Sections 6 When and how did Herzl develop Zionism? 20 JDC 4 Prime Minister’s Special Message • By GOL KALEV 22 Yad Labanim Editor’s Note 10 Statehood and spirit 16 Arab Press • By BENNY LAU 18 Three Ladies – Three Lattes 12 On the 70th anniversary of Mount Herzl 24 Wine Talk • By ARIEL FELDSTEIN 26 Food 13 Firsthand tales of Herzl from my grandfather 28 Tour Israel • By DAVID FAIMAN 32 Profle – Dr. Yitzhak Levy 14 Herzl’s ‘Altneuland’ mirrors today’s society 34 Observations • Interview with SHLOMO AVINERI 38 Books 42 Judaism 6 26 44 Games 46 Readers’ Photos 47 Arrivals COVER PHOTO: Dan Groover Arts (053-221-3734) Photos (from left) : Pascale Perez-Rubin and Neta Livneh; Marc Israel Sellem SAY WHAT? PHOTO OF THE WEEK | MARC ISRAEL SELLEM By LIAT COLLINS Tzchapha צ’פחה Meaning: A friendly, strong pat on the back/head Literally: From Arabic for a slap on the head Example: When they met up, the two guys gave each other a tzchapha. Z Editor: Erica Schachne Literary Editor: David Brinn Graphic Designer: Moran Snir Email: [email protected] Www.jpost.com >> Magazine 2 AUGUST 30, 2019 COVER NOTES A SPECIAL MESSAGE FROM PRIME MINISTER BENJAMIN NETANYAHU TO ‘MAGAZINE’ READERS erzl is our modern Moses. To and intelligence prowess is universally millions of our people would have been his people in bondage, he respected. -

LEBANESE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY Identity Through Imagery: the Palestinian Case by Rebecka Naim Farraj School of Arts and Sciences J

LEBANESE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY Identity through Imagery: The Palestinian Case By Rebecka Naim Farraj A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Affairs School of Arts and Sciences June 2014 Identity through Imagery: The Palestinian Case Rebecka Naim Farraj Abstract In 1948, Palestinians were dispersed after Al-Nakba in different regions around the world. Their status as being refugees, diasporas, or even citizens has become dependent to the country they reached, the hostland, after their exile. However, Palestinians have created transnational networks, disregarding the fact that their homeland was lost. These networks have helped in maintaining their collective identity. Based on the relation between the semiotics, constructivism, and transnationalism, this paper problematizes the status of Palestinians. It shows how images, more specifically posters, have played an important role in reflecting the identity of Palestinians. As for the framework of the comparative study, the countries to be taken into account are: Palestine, Lebanon, and the United States. Keywords: Palestinian Identity, Constructivism, Semiotics, Diaspora, Transnationalism, Poster. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I- Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1- Overview and Need for the Study ............................................................................. 3 1.2- Importance of Interdisciplinary Study .................................................................... -

Video Interview at Boston, Massachusetts by Alice Rothchild

Video interview at Boston, Massachusetts By Alice Rothchild Abdelfattah Abusrour transcript AR: Tell me your name, where you were born, the date of your birth. AA: Well, my name is Abdelfattah Abusrour. You can call me Abed. I was born in Aida refugee camp on the August the 12th, 1963. AR: And where was your family in 1948? AA: My father was born in a village called Bayt Nattif, which is 17 kilometers to the southwest of Jerusalem. My mother was born in a village called Zakariyya, which is not far away from there as well. So they were living in Bayt Nattif until the 19th of October, 1948. AR: And what were they doing? AA: My father was a merchant. He had a grocery store selling cereals and selling cloaks. They had sheep, a lot of sheep and goats and animals. They were doing a lot of farming for cereals: wheat, barley, and so on. My mother at that time didn’t work, but when they moved afterwards, running away from the village and so on, she become a midwife. AR: So did she have children when she was living in that village? AA: Yes. My eldest brother was born in 1945. My second brother in ‘47, and then she had a series of children born and dying. She gave birth to 14 and only four lived. Ten boys and four girls, only four boys lived and I was the youngest and I have another brother who was born in 1956 in the camp and I was the last to be born, the last to remain alive. -

The Representation of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in Palestinian Museums

The Yasser Arafat Museum Chapter Two MASTER THESIS: MUSEUM STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM THE REPRESENTATION OF THE PALESTINIAN-ISRAELI CONFLICT IN PALESTINIAN MUSEUMS THE YASSER ARAFAT MUSEUM, THE PALESTINIAN MUSEUM AND THE WALLED OFF ART HOTEL Shirin Husseini 11386118 Supervisor: Dr. Chiara De Cesari Second Reader: Dr. Mirjam Hoijtink Date of Completion: 29 March 2018 Word Count: 28,023 Front page image: Al-Nakba (Palestinian Catastrophe in 1948) exhibit in the Yasser Arafat Museum, Ramallah. Photograph Credit: (Yasser Arafat Museum, n.d.). i The Representation of The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in Palestinian Museums The Yasser Arafat Museum, The Palestinian Museum and the ‘Walled Off’ Art Hotel A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MA Museum Studies (Heritage Studies) March 2018 ii Abstract This thesis tackles the expansion of the museum sector in Palestine, and the noticeable emergence in the last few years of museums of a larger scale and higher quality, which try to contribute to the national narrative. In exploring this topic, I discuss the statelessness of Palestine and the lack of sovereignty of the Palestinian Authority, which has created a disorganised and unattended performance of different actors in the museum field. As a result, museums create their own narratives and display national history without any unifying national strategy to lead them. Through an analysis of three museums, each of which display narratives about contemporary Palestinian history, I argue that the different affiliations of these museums, their organisational structures, funding resources, and political ideologies, shape their representation of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. As the conflict is at the centre of Palestinian collective memory and national identity, this representation could be influential in the future of the Palestinian state-building endeavour. -

Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kent Academic Repository UNIVERSITY OF KENT SCHOOL OF ENGLISH ‘Bulwark against Asia’: Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. in Postcolonial Studies at University of Kent in 2015 by Nora Scholtes CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgments ii Abbreviations iii 1 INTRODUCTION: HERZL’S COLONIAL IDEA 1 2 FOUNDATIONS: ZIONIST CONSTRUCTIONS OF JEWISH DIFFERENCE AND SECURITY 40 2.1 ZIONISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM 42 2.2 FROM MINORITY TO MAJORITY: A QUESTION OF MIGHT 75 2.3 HOMELAND (IN)SECURITY: ROOTING AND UPROOTING 94 3 ERASURES: REAPPROPRIATING PALESTINIAN HISTORY 105 3.1 HIDDEN HISTORIES I: OTTOMAN PALESTINE 110 3.2 HIDDEN HISTORIES II: ARAB JEWS 136 3.3 REIMAGINING THE LAND AS ONE 166 4 ESCALATIONS: ISRAEL’S WALLING 175 4.1 WALLING OUT: FORTRESS ISRAEL 178 4.2 WALLED IN: OCCUPATION DIARIES 193 CONCLUSION 239 WORKS CITED 245 SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY 258 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a consideration of how the ideological foundations of Zionism determine the movement’s exclusive relationship with an outside world that is posited at large and the native Palestinian population specifically. Contesting Israel’s exceptionalist security narrative, it identifies, through an extensive examination of the writings of Theodor Herzl, the overlapping settler colonialist and ethno-nationalist roots of Zionism. In doing so, it contextualises Herzl’s movement as a hegemonic political force that embraced the dominant European discourses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including anti-Semitism. The thesis is also concerned with the ways in which these ideological foundations came to bear on the Palestinian and broader Ottoman contexts. -

The Inventory of Palestinian Embroidery Heritage

The inventory of Palestinian Embroidery Heritage File name: Peasant Embroidery (Skills, Practices, Knowledge and Rituals) Prepared by: Ministry of Culture Heritage Department / National Heritage Registry This file was submitted to His Excellency Minister of Culture, Dr. Atef Abu Saif, for approval and publishing at the Ministry’s web page Signature Dr. Atef Abu Saif Minister of Culture 1 An inventory of the element of the intangible cultural heritage 1. Defining the element of intangible cultural heritage 1. 1 Element Name: The Palestinian embroidery 1. 2 The element’s other names: peasant embroidery, peasant sew, peasant stitch, cross stitch. 1. 3 Domains of the intangible cultural heritage to which the element belongs: • Social practices, rituals and celebrations. • Knowledge and practices related to nature and the universe. • Skills related to traditional craft arts. • Oral traditions and expressions, including language, as a means of intangible cultural heritage. • Traditional handicrafts. 1. 4 The society or societies concerned with the element: 1. All Palestinians wherever they live, as embroidery is intertwined in many popular practices and rituals and it is an integral part of their wear, that is taught to daughters by their grandmothers and mothers. 2. Women and girls in Palestinian society as a whole, in cities, villages, and refugee camps, and wherever Palestinian women live in Palestine or in their places of refuge. 3. Institutions supporting the embroidery heritage done by male and female employees working in the workshops of charitable societies. 4. Factories’ and workshops’ owners who use embroidery units in their products such as workshops making accessories and traditional jewelry. 5. -

The Role of Collective Memory in Solidifying Identity: the Case of Palestinian Refugees

THE ROLE OF COLLECTIVE MEMORY IN SOLIDIFYING IDENTITY: THE CASE OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES By Ghaida Hamdan, BA, University of Alberta, 2018 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Immigration and Settlement Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Ghaida Hamdan, 2019 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER (MRP) I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this Major Research Paper. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. ii THE ROLE OF COLLECTIVE MEMORY IN SOLIDIFYING IDENTITY: THE CASE OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES Ghaida Hamdan Master of Arts 2019 Immigration and Settlement Studies Ryerson University ABSTRACT Through a critical review of scholarly literature on the role of collective memory as a resistance tool to memoricide, this research paper uses an analytical approach to examine the efforts exerted by Palestinian refugees in post 1948 Nakba (catastrophe of dispossession) to preserve and consolidate their national identity through the transmission of history of displacement and cultural heritage. With a specific focus on the fourth-generation Palestinian refugees living under occupation, and through studying cultural practices, oral history, and the Great March of Return Movement, this paper examines the role played by the collective memory in consolidating the Palestinians national identity in the post-Nakba era.