'On the Third Hand…'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I

JEWISH REVIEW Number 2, Summer 2010 $6.95 OF BOOKS Ruth R. Wisse The Poet from Vilna Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I. Cohen on Camondo Treasure David Sorkin on Steven J. Moses Zipperstein Montefiore The Spy who Came from the Shtetl Anita Shapira The Kibbutz and the State Robert Alter Yehuda Halevi Moshe Halbertal How Not to Pray Walter Russell Mead Christian Zionism Plus Summer Fiction, Crusaders Vanquished & More A Short History of the Jews Michael Brenner Editor Translated by Jeremiah Riemer Abraham Socher “Drawing on the best recent scholarship and wearing his formidable learning lightly, Michael Publisher Brenner has produced a remarkable synoptic survey of Jewish history. His book must be considered a standard against which all such efforts to master and make sense of the Jewish Eric Cohen past should be measured.” —Stephen J. Whitfield, Brandeis University Sr. Contributing Editor Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-14351-4 July Allan Arkush Editorial Board Robert Alter The Rebbe Shlomo Avineri The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson Leora Batnitzky Samuel Heilman & Menachem Friedman Ruth Gavison “Brilliant, well-researched, and sure to be controversial, The Rebbe is the most important Moshe Halbertal biography of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson ever to appear. Samuel Heilman and Hillel Halkin Menachem Friedman, two of the world’s foremost sociologists of religion, have produced a Jon D. Levenson landmark study of Chabad, religious messianism, and one of the greatest spiritual figures of the twentieth century.” Anita Shapira —Jonathan D. Sarna, author of American Judaism: A History Michael Walzer Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-13888-6 J. -

Can It Be That Our Dormant Language Has Been Wholly Revived?”: Vision, Propaganda, and Linguistic Reality in the Yishuv Under the British Mandate

Zohar Shavit “Can It Be That Our Dormant Language Has Been Wholly Revived?”: Vision, Propaganda, and Linguistic Reality in the Yishuv Under the British Mandate ABSTRACT “Hebraization” was a project of nation building—the building of a new Hebrew nation. Intended to forge a population comprising numerous lan- guages and cultural affinities into a unified Hebrew-speaking society that would actively participate in and contribute creatively to a new Hebrew- language culture, it became an integral and vital part of the Zionist narrative of the period. To what extent, however, did the ideal mesh with reality? The article grapples with the unreliability of official assessments of Hebrew’s dominance, and identifies and examines a broad variety of less politicized sources, such as various regulatory, personal, and commercial documents of the period as well as recently-conducted oral interviews. Together, these reveal a more complete—and more complex—portrait of the linguistic reality of the time. INTRODUCTION The project of making Hebrew the language of the Jewish community in Eretz-Israel was a heroic undertaking, and for a number of reasons. Similarly to other groups of immigrants, the Jewish immigrants (olim) who came to Eretz-Israel were required to substitute a new language for mother tongues in which they were already fluent. Unlike other groups Israel Studies 22.1 • doi 10.2979/israelstudies.22.1.05 101 102 • israel studies, volume 22 number 1 of immigrants, however, they were also required to function in a language not yet fully equipped to respond to all their needs for written, let alone spoken, communication in the modern world. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Early Zionist-Kurdish Contacts and the Pursuit of Cooperation: the Antecedents of an Alliance, 1931-1951 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2ds1052b Author Abramson, Scott Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Early Zionist-Kurdish Contacts and the Pursuit of Cooperation: the Antecedents of an Alliance, 1931-1951 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Scott Abramson 2019 © Copyright by Scott Abramson 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Early Zionist-Kurdish Contacts and the Pursuit of Cooperation: the Antecedents of an Alliance, 1931-1951 by Scott Abramson Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles Professor Lev Hakak, Co-Chair Professor Steven Spiegel, Co-Chair This study traces the progress of the contacts between Zionists/Israelis and Kurds—two non-Arab regional minorities intent on self-government and encircled by opponents—in their earliest stage of development. From the early 1930s to the early 1950s, the Political Department of the Jewish Agency (later, the Israeli Foreign Ministry) and several eminent Kurdish leaders maintained contact with a view to cooperation. The strategic calculus behind a Zionist/Israeli-Kurdish partnership was the same that directed Zionist/Israeli relations with all regional minorities: If demographic differences from the region’s Sunni Arab majority had made ii them outliers and political differences with them had made them outcasts, the Zionists/Israelis and the Kurds, together with their common circumstance as minorities, had a common enemy (Arab nationalists) against whom they could make common cause. -

Forms, Ideals, and Methods. Bauhaus Transfers to Mandatory Palestine

Ronny Schüler Forms, Ideals, and Methods. Bauhaus Transfers to Mandatory Palestine Introduction A “Bauhaus style” would be a setback to academic stagnation, into a state of inertia hostile to life, the combatting of which the Bauhaus was once founded. May the Bauhaus be saved from this death. Walter Gropius, 1930 The construction activities of the Jewish community in the British Mandate of Palestine represents a prominent paradigm for the spread of European avant-garde architecture. In the 1930s, there is likely no comparable example for the interaction of a similar variety of influences in such a confined space. The reception of architectural modernism – referred to as “Neues Bauen” in Germany – occurred in the context of a broad cultural transfer process, which had already begun in the wake of the waves of immigration (“Aliyot”) from Eu- rope at the end of the nineteenth century and had a formative effect within the emancipating Jewish community in Palestine (“Yishuv”). Among the growing number of immigrants who turned their backs on Europe with the rise of fas- cism and National Socialism were renowned intellectuals, artists, and archi- tects. They brought the knowledge and experience they had acquired in their 1 On the transfer process of modernity European homelands. In the opposite direction too, young people left to gain using the example of the British Mandate of Palestine, see. Heinze-Greenberg 2011; 1 professional knowledge, which was beneficial in their homeland. Dogramaci 2019; Stabenow/Schüler 2019. Despite the fact that, in the case of Palestine, the broad transfer processes were fueled by a number of sources and therefore represent the plurality of European architectural modernism, the Bauhaus is assigned outstanding 2 importance. -

The Promise and Failure of the Zionist-Maronite Relationship, 1920-1948

The Promise and Failure of the Zionist-Maronite Relationship, 1920-1948 Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Ilan Troen, Graduate Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Scott Abramson February 2012 Acknowledgements I cannot omit the expression of my deepest gratitude to my defense committee, the formidable triumvirate of Professors Troen, Makiya, and Salameh. To register my admiration for these scholars would be to court extravagance (and deplete a printer cartridge), so I shall have to limit myself to this brief tribute of heartfelt thanks. ii ABSTRACT The Promise and Failure of the Zionist-Maronite Relationship, 1920-1948 A thesis presented to the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Scott Abramson Much of the historiography on the intercourse between Palestinian Jews and Lebanese Maronites concerns only the two peoples’ relations in the seventies and eighties. This thesis, in contrast, attempts a departure from this scholarship, joining the handful of other works that chart the history of the Zionist-Maronite relationship in its earliest incarnation. From its inception to its abeyance beginning in 1948, this almost thirty-year relationship was marked by a search of a formal alliance. This thesis, by presenting a panoptical survey of early Zionist-Maronite relations, explores the many dimensions of this pursuit. It details the Zionists and Maronites’ numerous commonalities that made an alliance desirable and apparently possible; it profiles the specific elements among the Zionists and Maronites who sought an entente; it examines each of the measures the two peoples took to this end; and it analyzes why this protracted pursuit ultimately failed. -

Israel: Finding the Levant Within the Mediterranean

The Levantine Review Volume 1 Number 1 (Spring 2012) ISRAEL: FINDING THE LEVANT WITHIN THE MEDITERRANEAN Rachel S. Harris Alexandra Nocke. The Place of the Mediterranean in Modern Israeli Identity. Brill 2010, Cloth $70. ISBN 9789004173248 Amy Horowitz. Mediterranean Israeli Music and the Politics of the Aesthetic. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. Paper $29.95. ISBN 9780814334652. Karen Grumberg. Place and Ideology in Contemporary Hebrew Literature. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011. Cloth $39.95. ISBN 9780815632597. Zionism as a national movement sought to unite a dispersed people under a single conception of political sovereignty, with shared symbols of flag, anthem and language. Irrespective of where Jews had found a home during 2500 years of (at least symbolic) nomadic wandering, as guests in other lands, they would now return to their ancient homeland. For such an enterprise to succeed, a degree of homogenisation was required, where differences would be erased in favour of shared commonalities. These universalised conceptions for the new Jew were debated, explored, and decided upon by the leaders of the movement whose ideas were shaped by European theories of nationalism. From the beginning of the Zionist movement in the late nineteenth century and its territorialisation in Palestine, Jews faced the challenge of looking towards Europe socially and intellectually, while simultaneously attempting to situate themselves economically and physically within the landscape of the Middle East. This hybridity can be seen in a self-portrait by Shimon Korbman, a photographer working in Tel Aviv in the 1920s: Sitting on a small stool on the sand next to the sea, he faces the camera, dressed in his white tropical summer suit, an Arabic water pipe – Nargila –in his hand. -

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Jewish Statehood and the History of the Middle East Conflict First edition published by Ferdinand Schöningh GmbH & Co. KG in 2012: Das zionistische Israel. Jüdischer Nationalismus und die Geschichte des Nahostkonflikts An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-049663-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049880-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049564-5 ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, © 2017 Tamar Amar-Dahl, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. -

The Settler-Colonial Mythology Of

“GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 by Dustin Michael Naegle Bachelor of Science, 2004 Utah State University Logan, UT Master of Theological Studies, 2007 Brite Divinity School Fort Worth, TX Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Biblical Interpretation Fort Worth, TX April 2017 “GO UP (AGAIN) TO JERUSALEM IN JUDAH”: THE SETTLER-COLONIAL MYTHOLOGY OF “RETURN” AND “RESTORATION” IN EZRA 1–6 APPROVED BY THESIS COMMITTEE Claudia V. Camp Thesis Director David M. Gunn Reader Jeffrey Williams Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Joretta Marshall Dean For Dad (1958–1985) iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The list of people to whom I am indebted for the completion of this project exceeds far beyond what space allows. I am particularly thankful to my director and mentor Claudia V. Camp, who taught me what good scholarship is by challenging me intellectually and fostering my research interests. I am particularly thankful for the countless hours she devoted to reviewing and commenting on my work. Her guidance and support has profoundly influenced me as a scholar and as a human being. I am honored to have been her student. I am also thankful to David M. Gunn for his willingness to serve as a reader for this project. His insight and support proved to be invaluable. I also wish to thank Lorenzo Veracini, Patricia Lorcin, and Tamara Eskenazi who all provided helpful feedback. I would also like to thank the many teachers who helped shape my understanding of the world, particularly Warren Carter, Toni Craven, Steve Sprinkle, and Elaine Robinson. -

F Ine J Udaica

F INE J UDAICA . PRINTED BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHED LETTERS, MANUSCRIPTS AND CEREMONIAL &GRAPHIC ART K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 8TH, 2005 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 7 Catalogue of F INE J UDAICA . PRINTED BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHED LETTERS, MANUSCRIPTS AND CEREMONIAL &GRAPHIC ART From the Collection of Daniel M. Friedenberg, Greenwich, Conn. To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 8th February, 2005 at 2:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 6th February: 10:00 am–5:30 pm Monday, 7th February: 10:00 am–6:00 pm Tuesday, 8th February: 10:00 am–1:30 pm Important Notice: A Digital Image of Many Lots Offered in This Sale is Available Upon Request This Sale may be referred to as “Highgate” Sale Number Twenty Seven. Illustrated Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager : Margaret M. Williams Client Accounts: S. Rivka Morris Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Bezalel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Art Director & Photographer: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale please contact: Daniel E. Kestenbaum ❧ ❧ ❧ ORDER OF SALE Printed Books: Lots 1 – 222 Autographed Letters & Manuscripts: Lots 223 - 363 Ceremonial Arts: Lots 364 - End of Sale A list of prices realized will be posted on our Web site, www.kestenbaum.net, following the sale. -

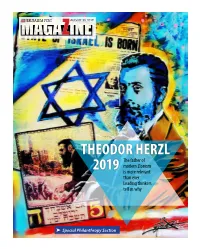

THEODOR HERZL the Father of Modern Zionism 2019 Is More Relevant Than Ever: Leading Thinkers Tell Us Why

Z AUGUST 30, 2019 THEODOR HERZL The father of modern Zionism 2019 is more relevant than ever: Leading thinkers tell us why ➤ Special Philanthropy Section CONTENTS August 30, 2019 Cover Philanthropy Sections 6 When and how did Herzl develop Zionism? 20 JDC 4 Prime Minister’s Special Message • By GOL KALEV 22 Yad Labanim Editor’s Note 10 Statehood and spirit 16 Arab Press • By BENNY LAU 18 Three Ladies – Three Lattes 12 On the 70th anniversary of Mount Herzl 24 Wine Talk • By ARIEL FELDSTEIN 26 Food 13 Firsthand tales of Herzl from my grandfather 28 Tour Israel • By DAVID FAIMAN 32 Profle – Dr. Yitzhak Levy 14 Herzl’s ‘Altneuland’ mirrors today’s society 34 Observations • Interview with SHLOMO AVINERI 38 Books 42 Judaism 6 26 44 Games 46 Readers’ Photos 47 Arrivals COVER PHOTO: Dan Groover Arts (053-221-3734) Photos (from left) : Pascale Perez-Rubin and Neta Livneh; Marc Israel Sellem SAY WHAT? PHOTO OF THE WEEK | MARC ISRAEL SELLEM By LIAT COLLINS Tzchapha צ’פחה Meaning: A friendly, strong pat on the back/head Literally: From Arabic for a slap on the head Example: When they met up, the two guys gave each other a tzchapha. Z Editor: Erica Schachne Literary Editor: David Brinn Graphic Designer: Moran Snir Email: [email protected] Www.jpost.com >> Magazine 2 AUGUST 30, 2019 COVER NOTES A SPECIAL MESSAGE FROM PRIME MINISTER BENJAMIN NETANYAHU TO ‘MAGAZINE’ READERS erzl is our modern Moses. To and intelligence prowess is universally millions of our people would have been his people in bondage, he respected. -

Narration of Palestine in Public Discursive Space in Canada

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-12-2014 12:00 AM The Violence of Representation: The (Un) Narration of Palestine in Public Discursive Space in Canada Peige Desjarlais The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Randa Farah The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Peige Desjarlais 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Desjarlais, Peige, "The Violence of Representation: The (Un) Narration of Palestine in Public Discursive Space in Canada" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2438. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2438 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VIOLENCE OF REPRESENTATION: THE (UN) NARRATION OF PALESTINE IN PUBLIC DISCURSIVE SPACE IN CANADA Monograph by Peige Desjarlais Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Peige Desjarlais 2014 Abstract The thesis examines representations of Palestine and Palestinians in Canada by drawing on the historical literature, statements from Canadian officials, media items, and through interviews conducted with Palestinian exiles in London and Toronto. Based on this research, I argue that the colonization of Palestine went, and still goes, hand in hand with a particular narrative construction in North America.