Mr. Wet-Brain” !

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Character Athlete Awards 2019

WINTER 2019 CHAMPIONSHIP RESULTS SPRING 2019 The Bulletin Character Athlete Awards 2019 - 2020 OFSAA Championship Calendar OFSAA Conference EDUCATION THROUGH SCHOOL SPORT LE SPORT SCOLAIRE : UN ENTRAINEMENT POUR LA VIE Ontario Federation of School Athletic Associations 305 Milner Avenue, Suite 207 Toronto, Ontario M1B 3V4 Website: www.ofsaa.on.ca Phone: (416) 426-7391 Publications Mail Agreement Number: 40050378 STAFF Executive Director Doug Gellatly P: 416.426.7438 [email protected] Sport Manager Shamus Bourdon P: 416.426.7440 [email protected] Program Manager Denise Perrier P: 416.426.7436 [email protected] Communications Coordinator Pat Park P: 416.426.7437 [email protected] Operations Coordinator Beth Hubbard P: 416.426.7439 [email protected] Sport Coordinator Peter Morris P: 905.826.0706 [email protected] Sport Coordinator Jim Barbeau P: 613.962.0148 [email protected] Sport Coordinator Brian Riddell P: 416.904.6796 [email protected] EXECUTIVE COUNCIL President Jennifer Knox, Kenner CI P: 705.743.2181 [email protected] Past President Ian Press, Bayside SS P: 613.966.2922 [email protected] Vice President Nick Rowe, Etobicoke CI P: 416.394.7840 [email protected] Metro Region Eva Roser, Blessed Cardinal Newman P: 416.393.5519 [email protected] East Region Kendra Read, All Saints HS P: 613.271.4254 x 5 [email protected] West Region Michele Van Bargen, Strathroy DCI P: 519.245.8488 [email protected] South Region Rob Thompson, St Aloysius Gonzaga P: 905.820.3900 [email protected] Central Region Shawn Morris, Stephen -

Director's Bulletin

Moving Forward as a Catholic Community of Hope December 15, 2008 Subjects: 1. CHRISTMAS MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION T 2. SAINTS OF THE TORONTO CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD H DIRECTOR’S E 3. ADVENT MESSAGES BULLETIN 4. CELEBRATING THE YEAR OF ST. PAUL 2008-2009 5. MEDIA SERVICES: CHRISTMAS VIDEOS--repeat 6. FEBRUARY IS PSYCHOLOGY MONTH: INVITATION TO SUBMIT ARTWORK In a school community 7. JUNIOR W5H formed by Catholic beliefs and traditions, 8. SPEECH & LANGUAGE “FOOD FOR TALK” COOKBOOK--repeat our Mission is to 9. SNOW PASS--repeat educate students 10. NO EARLY DISMISSAL NOTICE to their full potential 11. 2009 TD1 12. TRAVEL ALLOWANCE EXPENSE REPORTS--repeat 13. PAYROLL BULLETIN--repeat Charity 14. DEFERRED SALARY PLANS--repeat Virtue for the - Principals, Vice Principals & Coordinators Month of December - TSU - TECT - CUPE 3155 International Language Instructors Elementary 15. CATEGORY UPGRADING FORM, SECONDARY TEACHERS--repeat 16. CATEGORY UPGRADING FORM, ELEMENTARY TEACHERS— REVISED--repeat 17. FRENCH PUBLIC SPEAKING CONTESTS--repeat 18. TCDSB GOES GREEN!--repeat 19. AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIPS, BURSARIES & CONTESTS The year of St. Paul - Victor Angelosante Award--repeat Faith in Your Child The Toronto Catholic District School Board educates close to .......Cont’d 90,000 students from diverse cultures and language backgrounds in its 201 Catholic elementary and secondary schools and serves 475,032 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Toronto Catholic District School Board, 80 Sheppard Avenue East, Toronto, Ontario, M2N 6E8 Catholic school supporters across Telephone: 416-222-8282 the City of Toronto PLEASE ENSURE THAT A COPY OF THE WEEKLY DIRECTOR’S BULLETIN IS MADE ACCESSIBLE TO ALL STAFF #16 December 15, 2008 …continued Subjects: 20. -

Director's Bulletin

Validating our Mission/Vision May 16, 2005 T Subjects: RD H DIRECTOR’S CATHOLIC MISSIONS OF CANADA WEEK , WEEK OF MAY 23 E 1 SAINTS OF THE TORONTO CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD BULLETIN 2. MESSAGE FROM THE INTERIM DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION 2004-2005 3. FROM THE BOARD, HUMAN RESOURCES, PROGRAM & RELIGIOUS AFFAIRS COMMITTEE, May 5, 2005 We are Partners in 4. PAYROLL SCHEDULE--repeat - Secondary Teachers, Chaplains, Principals, Vice-Principals, Co-ordinators Catholic Education, - Elementary Teachers, Principals, Vice-Principals, Co-ordinators a Fellowship of - International Language Instructors - A.P.S.S.P. – 10-Month, 6-Day Employees Inspiration - CUPE 1328 SBESS and Unending - Payroll Bulletin Dedication. 5. SUMMERTIME SECURITY TIPS FOR SCHOOL EQUIPMENT 6. PORTUGUESE HISTORY AND HERITAGE MONTH 7. EDUCATIONAL STUDY TOUR IN ISRAEL 8. SPECTAGULAR—repeat A Community of Faith 9. RESULTS FROM GEOGRAPHY CHALLENGE 10. AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIPS, BURSARIES AND CONTESTS - Sapori e Saperi - 4th Annual Settimana Calabrese - CUPE Local 1328 Student Bursary--repeat With Heart in Charity 11. SCHOOL ANNIVERSARIES, OFFICIAL OPENINGS & BLESSINGS - Fr. Henry Carr’s 30th Anniversary--repeat - St. Michael’s 25th Anniversary--repeat 12. EVENTS/NOTICES - TCPVA Appreciation Dinner and Annual Awards--repeat Anchored in Hope - Beauty and the Beast, Staff Arts--repeat 13. SHARING OUR GOOD NEWS - St. Bruno Catholic School - St. Jerome Catholic School - St. Rose of Lima Catholic School - Brebeuf College School - Neil McNeil High School - Blessed Mother Teresa & Senator O’Connor - St. Michael’s Choir School - Notre Dame Catholic Secondary School - Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic School - St. Joseph Catholic School - TCDSB 20-Minute Make-Over - James Cardinal McGuigan Catholic High School - James Cardinal McGuigan C.H.S. -

31 Coventry St 416.466.1888 Scarborough, on Francisteam.Ca HOODQ HIGHLIGHTS

Robert Francis 31 Coventry St 416.466.1888 Scarborough, ON francisteam.ca HOODQ HIGHLIGHTS ELEMENTARY TRANSIT SAFETY SCHOOLS HIGH PARKS CONVENIENCE SCHOOLS PUBLIC SCHOOLS Your neighbourhood is part of a community of Public Schools offering Elementary, Middle, and High School programming. See the closest Public Schools near you below: Oakridge Junior Public School about a 7 minute walk - 0.5 KM away Elementary 110 Byng Ave, North York, ON M2N 4K4, Canada Oakridge Junior Public School is a Junior Kindergarten to Grade 4 community school with an enrolment of 800 students. As part of the Model Schools for Inner City initiative, the staff, parents and community are committed to providing a wide range of educational opportunities and rich learning experiences for all students. The Oakridge Way is the cornerstone of our school code of conduct and is in line with the Board's Character Development Program. At our monthly assemblies, we recognize excellence in academic achievement and social skills. At Oakridge we value our partnership with our parents who are actively involved in the education of their children through Family Nights, School Council, Nutrition programs, and school functions. http://www.tdsb.on.ca/FindYour/Schools.aspx?schno=4696 Address 110 Byng Ave, North York, ON M2N 4K4, Canada Language English Date Opened 01-09-1969 Grade Level Elementary School Code 4696 School Type Public Phone Number 416-396-6505 School Board Toronto DSB School Number 414387 Grades Offered PK to 4 School Board Number B66052 District Description Toronto and Area Regional Office Samuel Hearne Middle School about a 9 minute walk - 0.68 KM away Middle 21 Newport Ave, Scarborough, ON M1L, Canada We are a community of learners made up of students, teachers, support staff and parents. -

Appendix a Vendor No

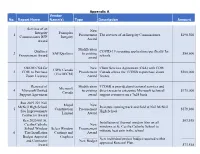

Appendix A Vendor No. Report Name Name(s) Type Description Amount Services of an New Integrity Principles 1 Procurement The services of an Integrity Commissioner. $190,500 Commissioner RFP Integrity Award Award Modification Qualtrics COVID-19 screening application specifically for 2 SAP/Qualtrics to existing $80,600 Procurement Award schools award OECM CSA for New Client Services Agreement (CSA) with CDW CDW Canada 3 CDW to Purchase Procurement Canada allows the TCDSB to purchase Zoom $300,000 (Via OECM) Zoom Licenses Award license Renewal of Modification TCDSB is provided professional services and Microsoft 4 Microsoft Unified to existing direct access to enterprise Microsoft technical $175,000 Canada Support Agreement award support resources on a 7x24 basis Ren 2019 221 Neil Mopal New McNeil High School Reinstate running track and field at Neil McNeil 5 Construction Procurement $579,860 Site Improvements High School Limited Award Contractor Award Ren 2020 001 St. $63,518 Installation of thermal window film on all Cecilia Catholic New windows at St. Cecilia Catholic School to School Window Select Window Procurement mitigate heat gain in the school 6 Tint Installation Coatings and Award _______________________ Budget Approval Graphics ________ _______ New individual project budget required within and Contractor New Budget approved Renewal Plan. Award $73,518 Appendix A Vendor No. Report Name Name(s) Type Description Amount Ren 2020 002 Immaculate New Energy conservation measures including Conception Catholic Procurement Upgrades and Retrocommissioning of HVAC $330,021 School Upgrades Active Award System at Immaculate Conception 7 and Mechanical ___________ ________________________________ _______ Retrocommissioning Budget Budget Increase and Scope Increase $377,899 of HVAC System - Increase Contractor Award Ren 2020 003 St. -

IBSC 15Th Annual Conference: New Worlds for Boys Toronto, Ontario, Canada

IBSC 15th Annual Conference: New Worlds for Boys Toronto, Ontario, Canada CONFERENCE COORDINATOR Richard Hood, Upper Canada College PARTNER SCHOOLS Brebeuf College Principal: Nick D'Avella Committee Member: Marianne Loranger Crescent School Head: Geoff Roberts Committee Member: Colin Lowndes Neil McNeil High School Principal: John Shanahan Committee Member: Mike Fellin Royal St. George's College Head: Hal Hannaford Committee Member: Catherine Kirkland St. Andrew's College Head: Ted Staunton Committee Member: Kevin McHenry The Sterling Hall School Head: Ian Robinson Committee Member: Luke Coles Upper Canada College Principal: Jim Power Committee Member: Mary Gauthier THE INTERNATIONAL BOYS’ SCHOOLS COALITION Brad Adams: Executive Director, IBSC Chris Wadsworth: Associate Executive Director, IBSC Kathleen Blaisdell: Executive Assistant, IBSC 1 IBSC 15th Annual Conference: New Worlds for Boys Toronto, Ontario, Canada Welcome to Toronto – and the 15th annual IBSC conference! It’s said that “Toronto” is derived from a local aboriginal word for “plenty of people” or “meeting place”. And indeed the city today is one of the world’s most multicultural cities – home to more than seventy differ- ent nationalities speaking some one hundred languages. It is thus fitting that Toronto is this year’s “meeting place” for IBSC educators from so many nations – Ja- pan, China, Spain, the United Kingdom, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, the United States and Can- ada. At its creation, the founders of the IBSC saw that it should be global in purpose and ambition, and we reap the benefits of this vision every time we meet. We hope that New Worlds for Boys will inspire you to envision dynamic ways to prepare boys for new worlds. -

Director's Bulletin

Validating our Mission/Vision May 30, 2005 T H DIRECTOR’S E Subjects: BULLETIN 1. SAINTS OF THE TORONTO CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD 2004-2005 2. PAYROLL SCHEDULE--repeat - Secondary Teachers, Chaplains, Principals, Vice-Principals, Co-ordinators - Elementary Teachers, Principals, Vice-Principals, Co-ordinators We are Partners in - International Language Instructors - A.P.S.S.P. – 10-Month, 6-Day Employees Catholic Education, - CUPE 1328 SBESS - Payroll Bulletin a Fellowship of Inspiration 3. EARLY DISMISSAL PRIOR TO SUMMER VACATION and Unending 4. READ-ALOUDS SUPPORT, LIBRARY SERVICES Dedication. 5. POPE JOHN PAUL II LIMITED EDITION PRINT 6. AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIPS, BURSARIES & CONTESTS - TCSB Employees’ Credit Union Limited Bursary 7. SCHOOL ANNIVERSARIES, OFFICIAL OPENINGS & BLESSINGS - St. Francis of Assisi’s Blessing & Spring Carnaval--repeat th A Community of Faith - Father Henry Carr’s 30 Anniversary 8. EVENTS/NOTICES - CUPE Local 1328 Year-End Soirée--repeat - Redmond Rocks Concert - St. Philip Neri presents Annie Jr. With Heart in Charity - Senator O’Connor’s Closing Time 9. SHARING OUR GOOD NEWS - St. John Catholic School - St. Louis Catholic School - Regina Mundi Catholic School Anchored in Hope - St. Joseph’s Catholic School - St. Andrew Catholic School - Neil McNeil High School - Michael Power/St. Joseph High School - St. Michael’s Choir School - Bishop Marrocco/Thomas Merton Catholic Secondary School - St. Joseph Morrow Park Catholic Secondary School - ESP Program 10. MEMORIALS 11. BIRTHS AND ADOPTIONS 12. CURRICULUM AND -

List of Schools and Boards Using Etms - October 23, 2020

List of Schools and Boards Using eTMS - October 23, 2020 Board Name School Name Algoma DSB ADSB Virtual Secondary School Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB ALCDSB Summer School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre-Con Ed Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Nicholson Catholic College Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Theresa Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Paul Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Regiopolis/Notre-Dame Catholic High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Holy Cross Catholic Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB South Huron District High School Avon Maitland DSB Stratford Ctr For Employment and Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Wingham Employment And Learning NS Avon Maitland -

Spiritan Magazine Vol. 31 No. 4 Calendar

Spiritan Magazine Volume 31 Number 4 Calendar Article 1 11-2007 Spiritan Magazine Vol. 31 No. 4 Calendar Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-tc Recommended Citation (2007). Spiritan Magazine Vol. 31 No. 4 Calendar. Spiritan Magazine, 31 (4). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-tc/vol31/iss4/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Spiritan Collection at Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spiritan Magazine by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Catholic Education: Nurturing Faith and Learning November 2007 / $2.50 From the Editor Volume 31, No. 4 Bringing Catholic November 2007 Spiritan is produced by The Congregation of the Holy Ghost TransCanada Province Education to Life Editors: Fr. Gerald FitzGerald Fr. Patrick Fitzpatrick glance along just one bookshelf in my room reveals the many-sided diamond Design & Production: Tim Faller Design Inc. that is Catholic Education: Educating for Life, Formation for Evangelization, A Strengthening the Heartbeat, Teaching with Fire, Reimagining the Catholic School, CONTENTS Teaching and Religious Imagination, Catholic Education and Politics in Ontario. More than forty years immersion in the sometimes turbulent waters of Catholic 2 From the Editor: Education has taught me a thing or two. My students, my colleagues, the parents, some Catholic Education insightful speakers and writers have educated me. I was far from fully prepared when I 3 Neil McNeil High School 1958-2008 stood in front of my first French class at Neil McNeil in 1964. I needed the challenge of the A Spiritan Endeavour religion classes in the 1970s, the four summers at Boston College’s Institute for Religious January — Thunder Bay CDSB. -

Liste Des Écoles Et Des Conseils Qui Utilisent Le Sgérn - 24 Juin 2021

Liste des écoles et des conseils qui utilisent le SGéRN - 24 juin 2021 Conseil École Algoma DSB ADSB Virtual Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Avon Maitland DSB Avon Maitland District E-Learning Centre Avon Maitland DSB Avon Maitland DSB Summer School Avon Maitland DSB Bluewater SS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Central Huron Adult Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Central Huron Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Dublin School - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB F E Madill Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Goderich District Collegiate Institute Avon Maitland DSB Listowel Adult Learning Centre NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Listowel District Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Milverton DHS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Mitchell Adult Learning Centre NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Mitchell District High School Avon Maitland -

List of Schools and Boards Using Etms - July 16, 2019

List of Schools and Boards Using eTMS - July 16, 2019 Board Name School Name Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB ALCDSB Summer School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre-Con Ed Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Nicholson Catholic College Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Theresa Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Paul Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Regiopolis/Notre-Dame Catholic High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Holy Cross Catholic Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB South Huron District High School Avon Maitland DSB Stratford Ctr For Employment and Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Wingham Employment And Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Seaforth DHS Night School - CLOSED -

Founders Wish Their Schools Farewell Spring 2014 / Volume 38, No

Founders wish their schools farewell Spring 2014 / Volume 38, No. 2 Spiritan is produced by The Congregation of the Holy Ghost, TransCanada Province Editor: Fr. Patrick Fitzpatrick CSSp Design & Production: Tim Faller Design Inc. contents 3 from the editor In weakness, strength 4 Farewell to the Beach Fond memories of other days From student to teacher to principal 4 10 Ukraine A spiritual journey in a political guise 12 Kindle in us the fire of your love 14 Brazil A presence in the favela 17 Youth in Latin America 10 Start where they find themselves 20 Papua New Guinea revisited 22 food for thought 23 home and away 14 Front cover: Photo courtesy of Neil McNeil High School Spiritan is published four times a year by the Spiritans, The Congregation of the Holy Ghost, 34 Collinsgrove Road, Scarborough, Ontario, M1E 3S4. Tel: 416-691-9319. Fax: 416-691-8760. E-mail: [email protected]. All correspon dence and changes of address should be sent to this address. One year subscription: $10.00. Printed by Torpedo Marketing, Vaughan, ON. Canadian Publications Mail Agreement no. 40050389. Registration No. 09612. Postage paid at Toronto, ON. Visit our website at www.spiritans.com from the editor In weakness, strength Pat Fitzpatrick CSSp entecost has come and gone. We recalled a frightened Today we are being invited to embrace a sense of mission group, huddled together in a borrowed building, the based not on strength, as perhaps in former times, but rooted Pdoors locked, the future uncertain, the present far in fragility and powerlessness.” from safe.