The Non-Jurors and Their History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

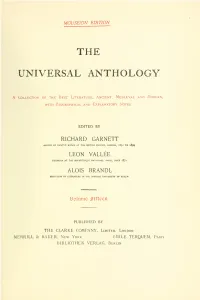

The Universal Anthology

MOUSEION EDITION THE UNIVERSAL ANTHOLOGY A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient, Medieval and Modern, WITH Biographical and Explanatory Notes EDITED BY RICHARD GARNETT KEEPER OF PRINTED BOOKS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, 185I TO 1899 LEON VALLEE LIBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQJJE NATIONALE, PARIS, SINCE I87I ALOIS BRANDL PKOFESSOR OF LITERATURE IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OP BERLIN IDoluine ififteen PUBLISHED BY THE CLARKE COMPANY, Limited, London MERRILL & BAKER. New York EMILE TERQUEM. Paris BIBLIOTHEK VERLAG, Berlin Entered at Stationers' Hall London, 1899 Droits de reproduction et da traduction reserve Paris, 1899 Alle rechte, insbesondere das der Ubersetzung, vorbehalten Berlin, 1899 Proprieta Letieraria, Riservate tutti i divitti Rome, 1899 Copyright 1899 by Richard Garnett IMMORALITY OF THE ENGLISH STAGE. 347 Young Fashion — Hell and Furies, is this to be borne ? Lory — Faith, sir, I cou'd almost have given him a knock o' th' pate myself. A Shoet View of the IMMORALITY AND PROFANENESS OF THE ENG- LISH STAGE. By JEREMY COLLIER. [Jeremy Collier, reformer, was bom in Cambridgeshire, England, in 1650. He was educated at Cambridge, became a clergyman, and was a " nonjuror" after the Revolution ; not only refusing the oath, but twice imprisoned, once for a pamphlet denying that James had abdicated, and once for treasonable corre- spondence. In 1696 he was outlawed for absolving on the scaffold two conspira- tors hanged for attempting William's life ; and though he returned later and lived unmolested in London, the sentence was never rescinded. Besides polemics and moral essays, he wrote a cyclopedia and an " Ecclesiastical IILstory of Great Britain," and translated Moreri's Dictionary. -

I the POLITICS of DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS

THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 by Loring Pfeiffer B. A., Swarthmore College, 2002 M. A., University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Loring Pfeiffer It was defended on May 1, 2015 and approved by Kristina Straub, Professor, English, Carnegie Mellon University John Twyning, Professor, English, and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, Courtney Weikle-Mills, Associate Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, English ii Copyright © by Loring Pfeiffer 2015 iii THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 Loring Pfeiffer, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 The Politics of Desire argues that late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women playwrights make key interventions into period politics through comedic representations of sexualized female characters. During the Restoration and the early eighteenth century in England, partisan goings-on were repeatedly refracted through the prism of female sexuality. Charles II asserted his right to the throne by hanging portraits of his courtesans at Whitehall, while Whigs avoided blame for the volatility of the early eighteenth-century stock market by foisting fault for financial instability onto female gamblers. The discourses of sexuality and politics were imbricated in the texts of this period; however, scholars have not fully appreciated how female dramatists’ treatment of desiring female characters reflects their partisan investments. -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY A

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY A comparative study of the High Church party in the dioceses of Chester and Bangor between 1688 and 1715. Wood, Craig David Award date: 2002 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 A Comparative Study of the High Church Party in the Dioceses of Chester and Bangor between 1688 and 1715 Craig David Wood i U.wem. v' ,,,. r>> . ýýYý_, 'd *************** ********************************************* ****** The following material has been excluded from the digitised copy due to 3`d Party Copyright restrictions: NONE Readers may consult the original thesis if they wish to see this material ***************** **************************ý********************* A Comparative Study of the High Church Party in the Dioceses of Chester and Bangor between 1688 and 1715 A Definition of High Churchmanship According to Diocesan Consensus Modern scholarship defines High Churchmanship as a distinct and partisan branch of the Anglican Church in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, especially in the context of religious intrigues in the houses of civil and church government in London. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

English Literature 1590 – 1798

UGC MHRD ePGPathshala Subject: English Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Paper 02: English Literature 1590 – 1798 Paper Coordinator: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad Module No 31: William Wycherley: The Country Wife Content writer: Ms.Maria RajanThaliath; St. Claret College; Bangalore Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad William Wycherley’s The Country Wife Introduction This lesson deals with one of the most famous examples of Restoration theatre: William Wycherley’s The Country Wife, which gained a reputation in its time for being both bawdy and witty. We will begin with an introduction to the dramatist and the form and then proceed to a discussion of the play and its elements and conclude with a survey of the criticism it has garnered over the years. Section One: William Wycherley and the Comedy of Manners William Wycherley (b.1640- d.1716) is considered one of the major Restoration playwrights. He wrote at a time when the monarchy in England had just been re-established with the crowning of Charles II in 1660. The newly crowned king effected a cultural restoration by reopening the theatres which had been shut since 1642. There was a proliferation of theatres and theatre-goers. A main reason for the last was the introduction of women actors. Puritan solemnity was replaced with general levity, a characteristic of the Caroline court. Restoration Comedy exemplifies an aristocratic albeit chauvinistic lifestyle of relentless sexual intrigue and conquest. The Comedy of Manners in particular, satirizes the pretentious morality and wit of the upper classes. -

The Development of the Study of Seventeenth-Century History Author(S): C

The Development of the Study of Seventeenth-Century History Author(s): C. H. Firth Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 7 (1913), pp. 25-48 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678415 Accessed: 26-06-2016 17:12 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press, Royal Historical Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society This content downloaded from 128.110.184.42 on Sun, 26 Jun 2016 17:12:47 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE STUDY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY HISTORY By Professor C. H. FIRTH, LL.D., F.B.A., President (1913). Read May 15, 1913. MY purpose is to trace the development of the study of one particular century in our national history, to show how the knowledge we now possess of it was acquired; how gradually the darkness which overhung the time was dissipated and the truth part by part revealed, and finally by what hands this work was achieved; and by what general causes its progress was promoted or retarded. -

James I and Gunpowder Treason Day.', Historical Journal., 64 (2)

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 01 October 2020 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Williamson, P. and Mears, N. (2021) 'James I and Gunpowder treason day.', Historical journal., 64 (2). pp. 185-210. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X20000497 Publisher's copyright statement: This article has been published in a revised form in Historical Journal https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X20000497. This version is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND. No commercial re-distribution or re-use allowed. Derivative works cannot be distributed. c The Author(s) 2020. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk JAMES I AND GUNPOWDER TREASON DAY* PHILIP WILLIAMSON AND NATALIE MEARS University of Durham Abstract: The assumed source of the annual early-modern English commemoration of Gunpowder treason day on 5 November – and its modern legacy, ‘Guy Fawkes day’ or ‘Bonfire night’ – has been an act of parliament in 1606. -

Historical Writing in Britain from the Late Middle Ages to the Eve of Enlightenment

Comp. by: pg2557 Stage : Revises1 ChapterID: 0001331932 Date:15/12/11 Time:04:58:00 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001331932.3D OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, 15/12/2011, SPi Chapter 23 Historical Writing in Britain from the Late Middle Ages to the Eve of Enlightenment Daniel Woolf Historical writing in Britain underwent extraordinary changes between 1400 and 1700.1 Before 1500, history was a minor genre written principally by clergy and circulated principally in manuscript form, within a society still largely dependent on oral communication. By the end of the period, 250 years of print and steadily rising literacy, together with immense social and demographic change, had made history the most widely read of literary forms and the chosen subject of hundreds of writers. Taking a longer view of these changes highlights continuities and discontinuities that are obscured in shorter-term studies. Some of the continu- ities are obvious: throughout the period the past was seen predominantly as a source of examples, though how those examples were to be construed would vary; and the entire period is devoid, with a few notable exceptions, of historical works written by women, though female readership of history was relatively common- place among the nobility and gentry, and many women showed an interest in informal types of historical enquiry, often focusing on familial issues.2 Leaving for others the ‘Enlightened’ historiography of the mid- to late eighteenth century, the era of Hume, Robertson, and Gibbon, which both built on and departed from the historical writing of the previous generations, this chapter suggests three phases for the principal developments of the period from 1400 to 1 I am grateful to Juan Maiguashca, David Allan, and Stuart Macintyre for their comments on earlier drafts of this essay, which I dedicate to the memory of Joseph M. -

Manuscripts Collected by Thomas Birch (B. 1705, D. 1766)

British Library: Western Manuscripts Manuscripts collected by Thomas Birch (b. 1705, d. 1766), D.D., and bequeathed by him to the British Museum, of which he was a Trustee from 1753 until his death ([1200-1799]) (Add MS 4101-4478) Table of Contents Manuscripts collected by Thomas Birch (b. 1705, d. 1766), D.D., and bequeathed by him to the British Museum, of which he was a Trustee from 1753 until his death ([1200–1799]) Key Details........................................................................................................................................ 1 Provenance........................................................................................................................................ 1 Add MS 4106–4107 TRANSCRIPTS OF STATE PAPERS and letters from public and private collections, made by or for Birch, together with.................................................................................... 8 Add MS 4109–4124 ANTHONY BACON TRANSCRIPTS.Transcripts and extracts of the correspondence of Anthony Bacon (d. 1601), chiefly in..................................................................................................... 19 Add MS 4128–4130 ESSEX (DEVEREUX) PAPERSTranscripts of original letters and papers in the British Museum, Lambeth Palace Library,............................................................................................. 32 Add MS 4133–4146 FORBES PAPERS. Vols. II–XV.4133–4146. Collections of Dr. Patrick Forbes, consisting of lists, copies, etc., of....................................................................................................... -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Discipline and local government in the Diocese of Durham, 1660-72. Brearley, J. D. How to cite: Brearley, J. D. (1974) Discipline and local government in the Diocese of Durham, 1660-72., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3450/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT OF THESIS For the realisation of the Restoration settlement of Church and State, it was essential that the central authorities received the co-operation of local officials who shared their aims and interests, and were prepared to re-establish and maintain order in the provinces. Cosin, Bishop of Durham, 1660-72, was the chief instrument of the government in the north-east of England. Within the Diocese he attempted to enforce universal compliance with the Church of England.