James I and Gunpowder Treason Day.', Historical Journal., 64 (2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stratford's the Merchant of Venice and Alabama Shakespeare Festival's the Winter's Tale

Vol. XVI THE • VPSTART • CR.OW Editor James Andreas Clemson University Founding Editor William Bennett The University of Tennessee at Martin Associate Editors Michael Cohen Murray State University Herbert Coursen Bowdoin College Charles Frey The University of Washington Marjorie Garber Harvard University Walter Haden The University of Tennessee at Martin Chris Hassel Vanderbilt University Maurice Hunt Baylor University Richard Levin The University of California, Davis John McDaniel Middle Tennessee State University Peter Pauls The University of Winnipeg Jeanne Roberts American University Production Editors Tharon Howard, Suzie Medders, and Deborah Staed Clemson University Editorial Assistants Martha Andreas, Kelly Barnes, Kati Beck, Dennis Hasty, Victoria Hoeglund, Charlotte Holt, Judy Payne, and Pearl Parker Copyright 1996 Clemson University All Rights Reserved Clemson University Digital Press Digital Facsimile Vol. XVI About anyone so great as Shakespeare, it is probable that we can never be right, it is better that we should from time to time change our way of being wrong. - T. S. Eliot What we have to do is to be forever curiously testing new opinions and courting new impressions. -Walter Pater The problems (of the arts) are always indefinite, the results are always debatable, and the final approval always uncertain. -Paul Valery Essays chosen for publication do not necessarily represent opin ions of the editor, associate editors, or schools with which any contributor is associated. The published essays represent a diver sity of approaches and opinions which we hope will stimulate interest and further scholarship. Subscription Information Two issues- $14 Institutions and Libraries, same rate as individuals- $14 two issues Submission of Manuscripts Essays submitted for publication should not exceed fifteen to twenty double spaced typed pages, including notes. -

The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack

TTHHEE GGUUNNPPOOWWDDEERR PPLLOOTT The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack Welcome to Heritage Doncaster’s the Gunpowder Plot activity pack. This booklet is filled with ideas that you can have a go at as a family at home whilst learning about the Gunpowder Plot. Some of these activities will require adult supervision as they require using an oven, a sharp implement, or could just be a bit tricky these have been marked with this warning triangle. We would love to see what you create so why not share your photos with us on social media or email You can find us at @doncastermuseum @DoncasterMuseum [email protected] Have Fun! Heritage Doncaster Education Service Contents What was the Gunpower Plot? Page 3 The Plotters Page 4 Plotters Top Trumps Page 5-6 Remember, remember Page 7 Acrostic poem Page 8 Tunnels Page 9 Build a tunnel Page 10 Mysterious letter Page 11 Letter writing Page 12 Escape and capture Page 13 Wanted! Page 14 Create a boardgame Page 15 Guy Fawkes Night Page 16 Firework art Page 17-18 Rocket experiment Page 19 Penny for a Guy Page 20 Sew your own Guy Page 21 Traditional Bonfire Night food Page 22 Chocolate covered apples Page 23 Wordsearch Page 24 What was the Gunpowder Plot? The Gunpowder Plot was a plan made by thirteen men to blow up the Houses of Parliament when King James I was inside. The Houses of Parliament is an important building in London where the government meet. It is made up of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. -

Th E Year in Review

2012 – 2013 T HE Y EAR IN R EVIEW C AMBRIDGE T HEOLOGICAL F EDERATION Contents Page Foreword from the Bishop of Ely 3 Principal’s Welcome 4 Highlights of the Year 7 The Year in Pictures 7 Cambridge Theological Federation 40th anniversary 8 Mission, Placements and Exchanges: 10 • Easter Mission 10 USA Exchanges 11 • Yale Divinity School 11 • Sewanee: The University of the South 15 • Hong Kong 16 • Cape Town 17 • Wittenberg Exchange 19 • India 20 • Little Gidding 21 Prayer Groups 22 Theological Conversations 24 From Westcott to Williams: Sacramental Socialism and the Renewal of Anglican Social Thought 24 Living and Learning in the Federation 27 Chaplaincy 29 • ‘Ministry where people are’: a view of chaplaincy 29 A day in the life... • Bill Cave 32 • Simon Davies 33 • Stuart Hallam 34 • Jennie Hogan 35 • Ben Rhodes 36 New Developments 38 Westcott Foundation Programme of Events 2013-2014 38 Obituaries and Appreciations 40 Remembering Westcott House 48 Ember List 2013 49 Staff contacts 50 Members of the Governing Council 2012 – 2013 51 Editor Heather Kilpatrick, Communications Officer 2012 – 2013 THE YEAR IN REVIEW Foreword from the Bishop of Ely It is a great privilege to have become the Chair of the Council of“ Westcott House. As a former student myself, I am conscious just how much the House has changed through the years to meet the changing demands of ministry and mission in the Church of England, elsewhere in the Anglican Communion and in the developing ecumenical partnerships which the Federation embodies. We have been at the forefront in the deliberations which have led to the introduction of the Common Awards. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5tv2w736 Author Harkins, Robert Lee Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. -

Tudors and the Reformation

Knowledge Organiser: Tudors and the Reformation The Catholic Church faced criticism in the Chronology: what happened on these dates? Vocabulary: define these words 16th century, leading to the Reformation. Martin Luther pins his ‘95 theses’ to the A promise to reduce time spent Some rulers left it and set up their own 1517 Indulgence churches, causing plots, revolts and wars. church door in Wittenberg. in purgatory. Summarise your learning Henry VIII declares himself head of the A movement that divided the 1534 Reformation Church of England. Christian Church in Europe. Criticisms The quality and practices of the of the Church were criticised by Martin The process of dissolving England’s A person that disagrees with the Catholic 1536 Heretic Luther. monasteries begins. official Church. Church Edward VI becomes king and begins to A group of Christians, who broke 1547 Protestant accelerate the Reformation in England. away from the Catholic Church. The Reformation spread across The belief that Jesus Christ is The Mary I becomes queen and tries to reverse Europe, weakening the position 1553 Transubstantiation physically present in the bread Reformation the Reformation in England. of the Catholic Church. and wine during mass. Elizabeth I succeeds Mary and sets up her Declaration that a marriage is 1559 Annulment Henry’s Henry VIII wanted a divorce and own Religious Settlement. invalid. ‘Great had to break from Rome to get Who were these people? What were these events? Matter’ one. The closure and sale of A former monk, who started the Protestant Dissolution Martin Luther England’s monasteries. Reformation in Europe. Impact of In England, the monasteries were Mary, Queen of A rival to the English throne, who fled there the dissolved and the Church Scots after her nobles revolted. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

The Story of a Man Called Daltone

- The Story of a Man called Daltone - “A semi-fictional tale about my Dalton family, with history and some true facts told; or what may have been” This story starts out as a fictional piece that tries to tell about the beginnings of my Dalton family. We can never know how far back in time this Dalton line started, but I have started this when the Celtic tribes inhabited Britain many yeas ago. Later on in the narrative, you will read factual information I and other Dalton researchers have found and published with much embellishment. There also is a lot of old English history that I have copied that are in the public domain. From this fictional tale we continue down to a man by the name of le Sieur de Dalton, who is my first documented ancestor, then there is a short history about each successive descendant of my Dalton direct line, with others, down to myself, Garth Rodney Dalton; (my birth name) Most of this later material was copied from my research of my Dalton roots. If you like to read about early British history; Celtic, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Knight's, Kings, English, American and family history, then this is the book for you! Some of you will say i am full of it but remember this, “What may have been!” Give it up you knaves! Researched, complied, formated, indexed, wrote, edited, copied, copy-written, misspelled and filed by Rodney G. Dalton in the comfort of his easy chair at 1111 N – 2000 W Farr West, Utah in the United States of America in the Twenty First-Century A.D. -

5302 the LONDON GAZETTE, 12 SEPTEMBER, 1941 Harold Ernest ANDREWS (103624)

5302 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12 SEPTEMBER, 1941 Harold Ernest ANDREWS (103624). John Charles William CODLING (103697). Richard Frank Dean ANDREWS (103625). Stanley Fife COLLINGS (103698). Leslie Kemp APPLETON (103626). Harold William Edward COLLINS (103699). Alan William Mason APPS''(103627). Roy Legassick COLLINS (103700). William Maurice ARCHER (103628). Edward Newcombe Gahan COOKE George Benjamin ARNOLD (103629). (103701). Wallace Haydn BASER (103630). Frederick Arthur COOKE (103702). Francis Howard BAGNALL (103631). Gordon Frederick COOKE (103703). Sidney Walter John BAKER (103632). Geoffrey Thomas COOMBS (103704). William Frederick BAKER (103633)? Thomas Hamilton COUTTS (103705). Charles Frederick BANNISTER (103634). Howard Hendley COUZENS (103706). Francis William BARNES (103635). Richard Macleod CUNNINGHAM (103707). Samuel George Gordon BARNHAM (103636). Paul Anderton Macgregor CURNOCK Clive Bernard BARRETT (103637). (103708). Harold Stanley George BARSON (103638). Ronald Parker CURTIS (103709). William Leslie BATH (103639). ° Reginald James DALE (103710). Norman Wardley BEARDSELL (103640). John DALGLEISH (103711). John Michael Lucas BEAUMONT (103641). Kenneth Ernest DARBY (103712). Harry Fisher BECKETT (103642).' Arthur Roydon DAVIES (103713). Herbert Valentine BEECROFT (103643). Ewart Glynne DAVIES (103714). Edgar William BELL (103644). Leslie DAVIES (103715). William Gordon BENNETT (103645). Oberlin Aylwin DAVIES (103716). Leslie Grainger BENTLEY (103646). Ronald Lewis DAVIES (103717). James William BERRY (103647). Thomas Reginald Daniel DAVIES (103718). Frederick Reginald BESTWICK (103648). Norman Leslie DAVIS (103719). Norman Cecil BETTLES (103649).. Wilfred Neville DEAN (103720). Frederick Maurice BEVAN (103650). Thomas Sanderson DEAS (103721). Eric Sidney BIRD (103651). Stuart Thomas James DENNIFORD Henry Alexander BIRD (103652).' (103722). Alan William BIRKETT (103653). Francis Sime DEWAR (103723). Thomas BISSETT (103654). Samuel William Charles DODWELL Harold William BLAKELEY (103655). (103724). Frederick Norman BLYTHE (103656). -

Queen Anne and the Arts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library TRANSITS Queen Anne and the Arts EDITED BY CEDRIC D. REVERAND II LEWISBURG BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS 14_461_Reverand.indb 5 9/22/14 11:19 AM Published by Bucknell University Press Copublished by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannery Street, London SE11 4AB All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data <insert CIP data> ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America 14_461_Reverand.indb 6 9/22/14 11:19 AM CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 1 “Praise the Patroness of Arts” 7 James A. Winn 2 “She Will Not Be That Tyrant They Desire”: Daniel Defoe and Queen Anne 35 Nicholas Seager 3 Queen Anne, Patron of Poets? 51 Juan Christian Pellicer 4 The Moral in the Material: Numismatics and Identity in Evelyn, Addison, and Pope 59 Barbara M. Benedict 5 Mild Mockery: Queen Anne’s Era and the Cacophony of Calm 79 Kevin L. -

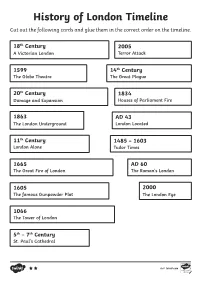

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four Hundred Years Ago, in 1605, a Man Called Guy Fawkes and a Group Of

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four hundred years ago, in 1605, a man called Guy Fawkes and a group of plotters attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London with barrels of gunpowder placed in the basement. They wanted to kill King James and the king’s leaders. Houses of Parliament, London Why did Guy Fawkes want to kill King James 1st and the king’s leaders? When Queen Elizabeth 1st took the throne of England she made some laws against the Roman Catholics. Guy Fawkes was one of a small group of Catholics who felt that the government was treating Roman Catholics unfairly. They hoped that King James 1st would change the laws, but he didn't. Catholics had to practise their religion in secret. There were even fines for people who didn't attend the Protestant church on Sunday or on holy days. James lst passed more laws against the Catholics when he became king. What happened - the Gunpowder Plot A group of men led by Robert Catesby, plotted to kill King James and blow up the Houses of Parliament, the place where the laws that governed England were made. Guy Fawkes was one of a group of men The plot was simple - the next time Parliament was opened by King James l, they would blow up everyone there with gunpowder. The men bought a house next door to the parliament building. The house had a cellar which went under the parliament building. They planned to put gunpowder under the house and blow up parliament and the king.