English Literature 1590 – 1798

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Dryden and the Late 17Th Century Dramatic Experience Lecture 16 (C) by Asher Ashkar Gohar 1 Credit Hr

JOHN DRYDEN AND THE LATE 17TH CENTURY DRAMATIC EXPERIENCE LECTURE 16 (C) BY ASHER ASHKAR GOHAR 1 CREDIT HR. JOHN DRYDEN (1631 – 1700) HIS LIFE: John Dryden was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was made England's first Poet Laureate in 1668. He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the “Age of Dryden”. The son of a country gentleman, Dryden grew up in the country. When he was 11 years old the Civil War broke out. Both his father’s and mother’s families sided with Parliament against the king, but Dryden’s own sympathies in his youth are unknown. About 1644 Dryden was admitted to Westminster School, where he received a predominantly classical education under the celebrated Richard Busby. His easy and lifelong familiarity with classical literature begun at Westminster later resulted in idiomatic English translations. In 1650 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1654. What Dryden did between leaving the university in 1654 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 is not known with certainty. In 1659 his contribution to a memorial volume for Oliver Cromwell marked him as a poet worth watching. His “heroic stanzas” were mature, considered, sonorous, and sprinkled with those classical and scientific allusions that characterized his later verse. This kind of public poetry was always one of the things Dryden did best. On December 1, 1663, he married Elizabeth Howard, the youngest daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st earl of Berkshire. -

Actresses (Self) Fashioning

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE INTERNATIONAL STUDIES INTERDISCIPLINARY POLITICAL AND CULTURAL JOURNAL, Vol. 16, No. 1/2014 97–110, DOI: 10.2478/ipcj-2014-0007 ∗ Raquel Serrano González,* Laura Martínez-García* HOW TO REPRESENT FEMALE IDENTITY ON THE ∗∗ RESTORATION STAGE: ACTRESSES (SELF) FASHIONING ABSTRACT: Despite the shifting ideologies of gender of the seventeenth century, the arrival of the first actresses caused deep social anxiety: theatre gave women a voice to air grievances and to contest, through their own bodies, traditional gender roles. This paper studies two of the best-known actresses, Nell Gwyn and Anne Bracegirdle, and the different public personae they created to negotiate their presence in this all—male world. In spite of their differing strategies, both women gained fame and profit in the male—dominated theatrical marketplace, confirming them as the ultimate “gender benders,” who appropriated the male role of family’s supporter and bread-winner. KEY WORDS: Actresses, Restoration, Bracegirdle, Gwyn, gender notions, deployment of alliance, deployment of sexuality. Introduction: Men, Women and Changing Gender Notions The early seventeenth century was an eventful time for Britain, a moment when turmoil and war gave way to a strict regime, which then resulted in the return of peace and stability in the form of Parliamentary Monarchy. The 1600s saw two of the most significant events in the history of the British Isles: the Civil War and the execution of Charles I. ∗ University of Oviedo, Dpto. Filología Anglogermánica y Francesa Teniente Alfonso Martínez s/n 33011 – Oviedo (Asturias). E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ∗∗ We gratefully acknowledge financial suport from FICYT under the research grant Severo Ochoa (BP 10-028). -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn As Life-Writing

This is a postprint! The Version of Record of this manuscript has been published and is available in Life Writing 13.4 (Taylor & Francis, 2016): 449-64. http://www.tandfonline.com/DOI: 10.1080/14484528.2015.1073715. ‘Rais’d from a Dunghill, to a King’s Embrace’: Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn as Life-Writing Dr. Julia Novak University of Salzburg Hertha Firnberg Research Fellow (FWF) Department of English and American Studies University of Salzburg Erzabt-Klotzstraße 1 5020 Salzburg AUSTRIA Tel. +43(0)699 81761689 Email: [email protected] This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under Grant T 589-G23. Abstract Nell Gwyn (1650-1687), one of the very early theatre actresses on the Restoration stage and long-term mistress to King Charles II, has today become a popular cultural icon, revered for her wit and good-naturedness. The image of Gwyn that emerges from Restoration satires, by contrast, is considerably more critical of the king’s actress-mistress. It is this image, arising from satiric references to and verse lives of Nell Gwyn, which forms the focus of this paper. Creating an image – a ‘likeness’ – of the subject is often cited as one of the chief purposes of biography. From the perspective of biography studies, this paper will probe to what extent Restoration verse satire can be read as life-writing and where it can be situated in the context of other 17th-century life-writing forms. It will examine which aspects of Gwyn’s life and character the satires address and what these choices reveal about the purposes of satire as a form of biographical storytelling. -

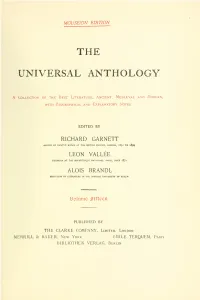

The Universal Anthology

MOUSEION EDITION THE UNIVERSAL ANTHOLOGY A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient, Medieval and Modern, WITH Biographical and Explanatory Notes EDITED BY RICHARD GARNETT KEEPER OF PRINTED BOOKS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, 185I TO 1899 LEON VALLEE LIBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQJJE NATIONALE, PARIS, SINCE I87I ALOIS BRANDL PKOFESSOR OF LITERATURE IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OP BERLIN IDoluine ififteen PUBLISHED BY THE CLARKE COMPANY, Limited, London MERRILL & BAKER. New York EMILE TERQUEM. Paris BIBLIOTHEK VERLAG, Berlin Entered at Stationers' Hall London, 1899 Droits de reproduction et da traduction reserve Paris, 1899 Alle rechte, insbesondere das der Ubersetzung, vorbehalten Berlin, 1899 Proprieta Letieraria, Riservate tutti i divitti Rome, 1899 Copyright 1899 by Richard Garnett IMMORALITY OF THE ENGLISH STAGE. 347 Young Fashion — Hell and Furies, is this to be borne ? Lory — Faith, sir, I cou'd almost have given him a knock o' th' pate myself. A Shoet View of the IMMORALITY AND PROFANENESS OF THE ENG- LISH STAGE. By JEREMY COLLIER. [Jeremy Collier, reformer, was bom in Cambridgeshire, England, in 1650. He was educated at Cambridge, became a clergyman, and was a " nonjuror" after the Revolution ; not only refusing the oath, but twice imprisoned, once for a pamphlet denying that James had abdicated, and once for treasonable corre- spondence. In 1696 he was outlawed for absolving on the scaffold two conspira- tors hanged for attempting William's life ; and though he returned later and lived unmolested in London, the sentence was never rescinded. Besides polemics and moral essays, he wrote a cyclopedia and an " Ecclesiastical IILstory of Great Britain," and translated Moreri's Dictionary. -

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

Studies in the Work of Colley Cibber

BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS HUMANISTIC STUDIES Vol. 1 October 1, 1912 No. 1 STUDIES IN THE WORK OF COLLEY CIBBER BY DE WITT C.:'CROISSANT, PH.D. A ssistant Professor of English Language in the University of Kansas LAWRENCE, OCTOBER. 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY CONTENTS I Notes on Cibber's Plays II Cibber and the Development of Sentimental Comedy Bibliography PREFACE The following studies are extracts from a longer paper on the life and work of Cibber. No extended investigation concerning the life or the literary activity of Cibber has recently appeared, and certain misconceptions concerning his personal character, as well as his importance in the development of English literature and the literary merit of his plays, have been becoming more and more firmly fixed in the minds of students. Cibber was neither so much of a fool nor so great a knave as is generally supposed. The estimate and the judgment of two of his contemporaries, Pope and Dennis, have been far too widely accepted. The only one of the above topics that this paper deals with, otherwise than incidentally, is his place in the development of a literary mode. While Cibber was the most prominent and influential of the innovators among the writers of comedy of his time, he was not the only one who indicated the change toward sentimental comedy in his work. This subject, too, needs fuller investigation. I hope, at some future time, to continue my studies in this field. This work was suggested as a subject for a doctor's thesis, by Professor John Matthews Manly, while I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago a number of years ago, and was con• tinued later under the direction of Professor Thomas Marc Par- rott at Princeton. -

I the POLITICS of DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS

THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 by Loring Pfeiffer B. A., Swarthmore College, 2002 M. A., University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Loring Pfeiffer It was defended on May 1, 2015 and approved by Kristina Straub, Professor, English, Carnegie Mellon University John Twyning, Professor, English, and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, Courtney Weikle-Mills, Associate Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, English ii Copyright © by Loring Pfeiffer 2015 iii THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 Loring Pfeiffer, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 The Politics of Desire argues that late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women playwrights make key interventions into period politics through comedic representations of sexualized female characters. During the Restoration and the early eighteenth century in England, partisan goings-on were repeatedly refracted through the prism of female sexuality. Charles II asserted his right to the throne by hanging portraits of his courtesans at Whitehall, while Whigs avoided blame for the volatility of the early eighteenth-century stock market by foisting fault for financial instability onto female gamblers. The discourses of sexuality and politics were imbricated in the texts of this period; however, scholars have not fully appreciated how female dramatists’ treatment of desiring female characters reflects their partisan investments. -

Women, Written in Stone Taking a Closer Look at Some of Chelsea’S Statues

Women, Written in Stone Taking a closer look at some of Chelsea’s statues Walking along the Embankment between Chelsea Old Church and Albert Bridge, the imposing statues of St Thomas More and Thomas Carlyle are hard to miss. Less obvious is a more modest commemoration, aptly doubling as bird-bath, featuring a line from the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, ‘He prayeth best who lovest best all things great and small’. It was commissioned as a memorial to Margaret Damer Dawson OBE (1873-1920), who lived opposite at 10 Cheyne Row. As Secretary of the Animal Defence and Anti-vivisection Society, she was one of the earliest animal rights campaigners. During the First World War, she broke the gender barrier by creating a volunteer cadre of women police officers, out of which the national Women’s Police Service would emerge. The Commemoration to Margaret Damer Dawson on Chelsea Embankment Damer Dawson has been commemorated with a fountain in her name, but are there any other sculptures in Chelsea depicting women, or celebrating their feats 25 WOMEN, WRITTEN IN Stone and talents? The short answer is yes, and…no. Figurative nudes, there are a plenty. In the gardens of Cadogan Place there are two: Girl with Doves and The Dancers. Both were sculpted by David Wynne OBE, another of whose works, Dancer with Bird can be found in Cadogan Square. Young Girl by karin Jonzen is located in Sloane Gardens. Retracing our steps back to Chelsea Embankment we will find Atalanta by Francis Derwent Wood RA and Awakening by his fellow Royal Academician, Gilbert Ledward. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

"Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2011 "Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World Jarred Wiehe Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wiehe, Jarred, ""Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 148. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/148 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/playyourfanexploOOwieh "Play your fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through The Country Wife, The Man of Mode, The Rover, and The Way of the World By Jarred Wiehe A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program For Honors in the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In English Literature, College of Letters and Sciences, Columbus State University x Thesis Advisor Date % /Wn l ^ Committee Member Date Rsdftn / ^'7 CSU Honors Program Director C^&rihp A Xjjs,/y s z.-< r Date <F/^y<Y'£&/ Wiehe 1 'Play your fan': Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage through The Country Wife, The Man ofMode, The Rover, and The Way of the World The full irony and wit of Restoration comedies relies not only on what characters communicate to each other, but also on what they communicate to the audience, both verbally and physically. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials .....................................................................................................................................