Liminal Figures, Liminal Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust : the Documentary Evidence / Introduction by Henry J

D 804 .3 H655 1993 ..v** \ ”>k^:>00'° * k5^-;:^C ’ * o4;^>>o° • ’>fe £%' ’5 %^S' w> «* O p N-4 ^ y° ^ ^ if. S' * * ‘/c*V • • •#• O' * ^V^A. f ° V0r*V, »■ ^^hrJ 0 ° "8f °^; ^ " ^Y> »<<■ °H° %>*,-’• o/V’m*' ( ^ »1 * °* •<> ■ 11 • 0Vvi » » !■„ V " o « % Jr % > » *"'• f ;M’t W ;• jfe*-. w 4»Yv4-W-r ' '\rs9 - ^ps^fc 1 v-v « ^ o f SI ° ^SJJV o J o cS^f) 2 IISII - ?%^ * .v W$M : <yj>A. * * A A, o WfyVS? =» _ 0 c^'Tn ft / /, , *> -X- V^W/.ov o e b' j . &? \v 'Mi.»> 'Sswr o, J?<v.v w lv4><k\NJ * ^ ^ . °o \V<<> x<P o* Sffli: "£? iiPli5 XT i^sm” TT - W"» w *<|E5»; •J.oJ%P/ y\ %^p»# j*\ °*Ww; 4?% « ^WmW^O . *S° * l>t-»^\V, ” * CTo4;^o° * * : • o°^4oo° • V'O « •: v .••gpaV. \* :f •: K:#i K •#;o K il|:>C :#• !&: V ; ", *> Q *•a- vS#^.//'n^L;V *y* >wT<^°x- *** *jt 1' , ,»*y co ' >n 9 v3 ^S'J°'%‘,“'" V’t'^X,,“°y°>*e,°'S,',n * • • C\,'“K°,45»,-*<>A^'” **^*. f°C 8 ^\W- A/.fef;^ tM; i\ ^ # # ^ *J0g§S 4'°* ft V4°/ rv j- ^ O >?'V 7!&l'ev ❖ ft r Oo ^4#^irJ> 1fS‘'^s3:i ^ O >P-4* ^ rf-^ *2^70^ -r ^ ^ ._ * \44\§s> u _ ^,§<!, <K 4 L< « ,»9vyv%s« »,°o,'*»„;,* 4*0 “» o°, 1.0, -r X*MvV/'Sl'" *>4v >X'°*°y'(• > /4>-' K ** <T ^ r 4TSS "oz Vv «r >j,'j‘ cpS'a" WMW » » ,©fi^ * c^’tw °,ww * <^v4 *1 3 V/fF'-k^k z “y^3ts.\N ^ <V'’ ^V> , '~^>S/ ji^ * »j, o a> ’Cf' Q ,7—-. -

Education with Testimonies, Vol.4

Education with Testimonies, Vol.4 Education with Testimonies, Vol.4 INTERACTIONS Explorations of Good Practice in Educational Work with Video Testimonies of Victims of National Socialism edited by Werner Dreier | Angelika Laumer | Moritz Wein Published by Werner Dreier | Angelika Laumer | Moritz Wein Editor in charge: Angelika Laumer Language editing: Jay Sivell Translation: Christopher Marsh (German to English), Will Firth (Russian to English), Jessica Ring (German to English) Design and layout: ruf.gestalten (Hedwig Ruf) Photo credits, cover: Videotaping testimonies in Jerusalem in 2009. Eyewitnesses: Felix Burian and Netty Burian, Ammnon Berthold Klein, Jehudith Hübner. The testimonies are available here: www.neue-heimat-israel.at, _erinnern.at_, Bregenz Photos: Albert Lichtblau ISBN: 978-3-9818556-2-3 (online version) ISBN: 978-3-9818556-1-6 (printed version) © Stiftung „Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” (EVZ), Berlin 2018 All rights reserved. The work and its parts are protected by copyright. Any use in other than legally authorized cases requires the written approval of the EVZ Foundation. The authors retain the copyright of their texts. TABLE OF CONTENTS 11 Günter Saathoff Preface 17 Werner Dreier, Angelika Laumer, Moritz Wein Introduction CHAPTER 1 – DEVELOPING TESTIMONY COLLECTIONS 41 Stephen Naron Archives, Ethics and Influence: How the Fortunoff Video Archive‘s Methodology Shapes its Collection‘s Content 52 Albert Lichtblau Moving from Oral to Audiovisual History. Notes on Praxis 63 Sylvia Degen Translating Audiovisual Survivor Testimonies for Education: From Lost in Translation to Gained in Translation 76 Éva Kovács Testimonies in the Digital Age – New Challenges in Research, Academia and Archives CHAPTER 2 – TESTIMONIES IN MUSEUMS AND MEMORIAL SITES 93 Kinga Frojimovics, Éva Kovács Tracing Jewish Forced Labour in the Kaiserstadt – A Tainted Guided Tour in Vienna 104 Annemiek Gringold Voices in the Museum. -

Italian Cinema As Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr

ENGL 2090: Italian Cinema as Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr. Lisa Verner [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys Italian cinema during the postwar period, charting the rise and fall of neorealism after the fall of Mussolini. Neorealism was a response to an existential crisis after World War II, and neorealist films featured stories of the lower classes, the poor, and the oppressed and their material and ethical struggles. After the fall of Mussolini’s state sponsored film industry, filmmakers filled the cinematic void with depictions of real life and questions about Italian morality, both during and after the war. This class will chart the rise of neorealism and its later decline, to be replaced by films concerned with individual, as opposed to national or class-based, struggles. We will consider the films in their historical contexts as literary art forms. REQUIRED TEXTS: Rome, Open City, director Roberto Rossellini (1945) La Dolce Vita, director Federico Fellini (1960) Cinema Paradiso, director Giuseppe Tornatore (1988) Life is Beautiful, director Roberto Benigni (1997) Various articles for which the instructor will supply either a link or a copy in an email attachment LEARNING OUTCOMES: At the completion of this course, students will be able to 1-understand the relationship between Italian post-war cultural developments and the evolution of cinema during the latter part of the 20th century; 2-analyze film as a form of literary expression; 3-compose critical and analytical papers that explore film as a literary, artistic, social and historical construct. GRADES: This course will require weekly short papers (3-4 pages, double spaced, 12- point font); each @ 20% of final grade) and a final exam (20% of final grade). -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The American Film Musical and the Place(Less)Ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’S “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis

humanities Article The American Film Musical and the Place(less)ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’s “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis Florian Zitzelsberger English and American Literary Studies, Universität Passau, 94032 Passau, Germany; fl[email protected] Received: 20 March 2019; Accepted: 14 May 2019; Published: 19 May 2019 Abstract: This article looks at cosmopolitanism in the American film musical through the lens of the genre’s self-reflexivity. By incorporating musical numbers into its narrative, the musical mirrors the entertainment industry mise en abyme, and establishes an intrinsic link to America through the act of (cultural) performance. Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope and its recent application to the genre of the musical, I read the implicitly spatial backstage/stage duality overlaying narrative and number—the musical’s dual registers—as a means of challenging representations of Americanness, nationhood, and belonging. The incongruities arising from the segmentation into dual registers, realms complying with their own rules, destabilize the narrative structure of the musical and, as such, put the semantic differences between narrative and number into critical focus. A close reading of the 1972 film Cabaret, whose narrative is set in 1931 Berlin, shows that the cosmopolitanism of the American film musical lies in this juxtaposition of non-American and American (at least connotatively) spaces and the self-reflexive interweaving of their associated registers and narrative levels. If metalepsis designates the transgression of (onto)logically separate syntactic units of film, then it also symbolically constitutes a transgression and rejection of national boundaries. In the case of Cabaret, such incongruities and transgressions eventually undermine the notion of a stable American identity, exposing the American Dream as an illusion produced by the inherent heteronormativity of the entertainment industry. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Myth of the Good Italian in the Italian Cinema

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 16 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy July 2014 The Myth of the Good Italian in the Italian Cinema Sanja Bogojević Faculty of Philosophy, University of Montenegro Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n16p675 Abstract In this paper we analyze the phenomenon called the “myth of the good Italian” in the Italian cinema, especially in the first three decades of after-war period. Thanks to the recent success of films such as Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds or Academy Award- winning Benigni’s film La vita è bella and Spielberg’s Schindler’s List it is commonly believed that the Holocaust is a very frequent and popular theme. Nevertheless, this statement is only partly true, especially when it comes to Italian cinema. Soon after the atrocities of the WWII Italian cinema became one of the most prominent and influential thanks to its national film movement, neorealism, characterized by stories set amongst the poor and famished postwar Italy, celebrating the fight for freedom under the banners of Resistance and representing a nation opposed to the Fascist and Nazi regime. Interestingly, these films, in spite of their very important social engagement, didn’t even mention the Holocaust or its victims and it wasn’t until the 1960’s that Italian cinema focused on representing and telling this horrific stories. Nevertheless, these films represented Italians as innocent and incapable of committing cruel acts. The responsibility is usually transferred to the Germans as typically cold and sadistic, absolving Italians of their individual and national guilt. -

Fondo Liliana Cavani Elenco Di Consistenza Aggiornato A

)RQGR/LOLDQD&DYDQL (OHQFRGLFRQVLVWHQ]DDJJLRUQDWRD RWWREUH (HFRQVXFFHVVLYHDJJLXQWH) &2//2&$=,21(H %5(9('(6&5,=,21( 48$17,7$¶ &21',=,21$0(172 0$7(5,$/('2&80(17$5,2 Armadio ) RIPIANO N. SCATOLA n. 1a 1) Articoli/interviste del periodo in cui Cavani è Consigliere Amm. RAI 2) Varie del 2000 (articoli e lettere) 3) Redazione 2000 4) Revisione del 2000 5) “Progetto Moro” (articoli di giornale dal 1967 al 1979) SCATOLA n. 2a 1) “Galileo”, copione originale, con 1 vol. acclusi documenti. 2) “Milarepa” Documentazione diversa relativa alla lavorazione del film”, anno 1971/1972. 3) Appunti per Francesco, 1965. SCATOLA n. 3a 1) “Oltre la porta” copione in lingua 1 vol. inglese 2) “La pelle “ copione in italiano per il 1 vol. cinema 3) “La pelle” copione in italiano per la 1 vol. televisione 4) “Al di là del bene e del male” 1 vol. dialoghi in inglese 5) “Al di là del bene e del male” 1 vol. dialoghi in italiano 6) “La pelle” copione bilingue per il 1 vol. cinema 7) “La pelle” copione bilingue per la 1 vol. televisione SCATOLA n. 4a 1) “Il portiere di notte” dialoghi 2 vol. aggiornati in inglese 2) “Il portiere di notte” dialoghi 1 vol. aggiornati in inglese e italiano 3) “Il portiere di notte” master, 1 vol. dialoghi in italiano 4) “Il portiere di notte” copione 2 vol. 5) “The Night Porter” 1 vol. copione in inglese 6) “Galileo” fotocopie dialoghi 7) “Francesco e Galileo: due film”, fotocopie del libro SCATOLA n. 5a 1) “L’Ospite” dialoghi in italiano 1 vol. -

William A. Seiter ATTORI

A.A. Criminale cercasi Dear Brat USA 1951 REGIA: William A. Seiter ATTORI: Mona Freeman; Billy DeWolfe; Edward Arnold; Lyle Bettger A cavallo della tigre It. 1961 REGIA: Luigi Comencini ATTORI: Nino Manfredi; Mario Adorf; Gian Maria Volont*; Valeria Moriconi; Raymond Bussires L'agente speciale Mackintosh The Mackintosh Man USA 1973 REGIA: John Huston ATTORI: Paul Newman; Dominique Sanda; James Mason; Harry Andrews; Ian Bannen Le ali della libert^ The Shawshank Redemption USA 1994 REGIA: Frank Darabont ATTORI: Tim Robbins; Morgan Freeman; James Whitmore; Clancy Brown; Bob Gunton Un alibi troppo perfetto Two Way Stretch GB 1960 REGIA: Robert Day ATTORI: Peter Sellers; Wilfrid Hyde-White; Lionel Jeffries All'ultimo secondo Outlaw Blues USA 1977 REGIA: Richard T. Heffron ATTORI: Peter Fonda; Susan Saint James; John Crawford A me la libert^ A nous la libert* Fr. 1931 REGIA: Ren* Clair ATTORI: Raymond Cordy; Henri Marchand; Paul Olivier; Rolla France; Andr* Michaud American History X USA 1999 REGIA: Tony Kaye ATTORI: Edward Norton; Edward Furlong; Stacy Keach; Avery Brooks; Elliott Gould Gli ammutinati di Sing Sing Within These Walls USA 1945 REGIA: Bruce H. Humberstone ATTORI: Thomas Mitchell; Mary Anderson; Edward Ryan Amore Szerelem Ung. 1970 REGIA: K‡roly Makk ATTORI: Lili Darvas; Mari T*r*csik; Iv‡n Darvas; Erzsi Orsolya Angelo bianco It. 1955 REGIA: Raffaello Matarazzo ATTORI: Amedeo Nazzari; Yvonne Sanson; Enrica Dyrell; Alberto Farnese; Philippe Hersent L'angelo della morte Brother John USA 1971 REGIA: James Goldstone ATTORI: Sidney Poitier; Will Geer; Bradford Dillman; Beverly Todd L'angolo rosso Red Corner USA 1998 REGIA: Jon Avnet ATTORI: Richard Gere; Bai Ling; Bradley Whitford; Peter Donat; Tzi Ma; Richard Venture Anni di piombo Die bleierne Zeit RFT 1981 REGIA: Margarethe von Trotta ATTORI: Jutta Lampe; Barbara Sukowa; RŸdiger Vogler Anni facili It. -

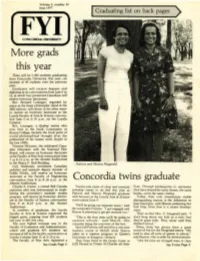

Grads Thi~ Year Concordia Twins Graduate

Volume 3, number 27 Ju11e 1977 Graduating list on back pages ) ,. I.,___ _ _____, FYI~ ... CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY More grads thi~ year There will be 2,383 students graduating · from Concordia University this year-an increase of 49 students over the previous year. Graduates will receive degrees and diplomas it six convocations from June 5 to 12, at which four prominent Canadians will receive honorary doctorates. Rev. Bernard Lonergan, regarded by many as the finest philosophic mind of the 20th century, will return to his alma mater to receive an honorary doctorate at the Loyola Faculty of Arts & Science convoca tion June 5 at 2 :15 p.m. on the Loyola Campus. Rev. Lonergan, a Quebec native who now lives in the Jesuit Community at Boston College, became the focal point of world philosophical thought after the publication of his master work Insight in the late 1950s. Norman McLar~n, the celebrated Cana dian filmmaker with the National Film Board, will receive an honorary doctorate at the Faculty of Fine Arts convocation June 7 at 8 : 15 p.m. at the Alumni Auditorium in the Henry F. Hall Building. Patricia and Sharon Fitzgerald Guy Desbarats, prominent Canadian architect and assistant deputy minister of Public Works, will receive an honorary doctorate at the Faculty of Engineering convocation June 8 at 8:15 p.m. at the Concordia twins graduate Alumni Auditorium. Charles S. Carter, a retired Bell Canada Twenty-one years of close and constant lives. Through kindergarten to university executive who was instrumental in estab twinship comes to an end this year as they have shared the same classes, the same lishing the university's modular studies Patricia and Sharon Fitzgerald graduate books-even the same clothes. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Nonprofessional Acting in El Perro Issue 9 | Movie: a Journal of Film Criticism | 56

Nonprofessional Acting in El Perro Issue 9 | Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism | 56 interpretable, or because the performers are, from this initial is also renamed after the non-actor, which makes it easier for contact with the filmmaking devices, modifying their behav- the performer to identify with the role. On set, scripts are iour and incorporating gestures and mannerisms. For these withheld from the non-actors, favouring instead the use of filmmakers it is the contact with the camera (the recording cues and verbal explanations. (This alleviates the performer’s device) that inevitably changes the person’s behaviour and possible difficulties memorising lines.) Non-actors are also their status as film performers. encouraged to adapt words and sentences to their natural way Robert Bresson, who made the use of non-actors a dis- of speaking. Sorin also shoots in chronological order (Sorin tinctive feature of his filmmaking style, would disagree. For in Ponce 2004), a technique facilitated by the use of a small Bresson what radically altered the non-actor’s behaviour and production crew. The shooting ratio is very high, often above their status was not performing for the camera but watching thirty to one, as scenes are not rehearsed; rather, all rehearsals their own on-screen performance. Bresson explains: are filmed. Do not use the same models in two films. […] They would These choices, popular among social realist filmmak- look at themselves in the first film as one looks at one- ers such as Ken Loach, help withhold fictional events from Nonprofessional Acting self in the mirror, would want people to see them as they the performer so that actor and character discover them wish to be seen, would impose a discipline on themselves, simultaneously.4 The emphasis is on preserving a quality of in El Perro would grow disenchanted as they correct themselves.