Copyright by Jodi Heather Egerton 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Cinema As Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr

ENGL 2090: Italian Cinema as Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr. Lisa Verner [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys Italian cinema during the postwar period, charting the rise and fall of neorealism after the fall of Mussolini. Neorealism was a response to an existential crisis after World War II, and neorealist films featured stories of the lower classes, the poor, and the oppressed and their material and ethical struggles. After the fall of Mussolini’s state sponsored film industry, filmmakers filled the cinematic void with depictions of real life and questions about Italian morality, both during and after the war. This class will chart the rise of neorealism and its later decline, to be replaced by films concerned with individual, as opposed to national or class-based, struggles. We will consider the films in their historical contexts as literary art forms. REQUIRED TEXTS: Rome, Open City, director Roberto Rossellini (1945) La Dolce Vita, director Federico Fellini (1960) Cinema Paradiso, director Giuseppe Tornatore (1988) Life is Beautiful, director Roberto Benigni (1997) Various articles for which the instructor will supply either a link or a copy in an email attachment LEARNING OUTCOMES: At the completion of this course, students will be able to 1-understand the relationship between Italian post-war cultural developments and the evolution of cinema during the latter part of the 20th century; 2-analyze film as a form of literary expression; 3-compose critical and analytical papers that explore film as a literary, artistic, social and historical construct. GRADES: This course will require weekly short papers (3-4 pages, double spaced, 12- point font); each @ 20% of final grade) and a final exam (20% of final grade). -

Johnny Stecchino with Roberto Benigni and Nicoletta Braschi Selected Bibliography

Johnny Stecchino with Roberto Benigni and Nicoletta Braschi Selected Bibliography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Roberto Benigni Bullaro, Grace R. Beyond "Life Is Beautiful": Comedy and Tragedy in the Cinema of Roberto Benigni. Leicester: Troubador, 2005. Celli, Carlo. “Comedy and the Holocaust in Roberto Benigni’s Life Is Beautiful/La vita è bella.” in The Changing Face of Evil in Film and Television. Martin F. Norden (ed). Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2007. 145-158. ---. The Divine Comic: The Cinema of Roberto Benigni. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2001. Consolo, Salvatore. “The Watchful Mirror: Pinocchio’s Adventures Recreated by Roberto Benigni.” in Pinocchio, Puppets, and Modernity: The Mechanical Body. Katie Pizzi (ed). New York: Routledge, 2012. Gordon, Robert S. C. “Real Tanks and Toy Tanks: Playing Games with History in Roberto Benigni's La vita è bella/Life Is Beautiful.” Studies in European Cinema 2.1 (2005): 31-44. Kertzer, Adrienne. Like a Fable, Not a Pretty Picture: Holocaust Representation in Roberto Benigni and Anita Lobel. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2000. Kroll, Pamela L. “Games of Disappearance and Return: War and the Child in Roberto Benigni's Life Is Beautiful.” Literature Film Quarterly 30.1 (2002): 29-45. -

Ephemeral Games: Is It Barbaric to Design Videogames After Auschwitz?

Ephemeral games: Is it barbaric to design videogames after Auschwitz? © 2000 Gonzalo Frasca ([email protected]) Reproduction forbidden without written authorization from the autor. Originally published in the Cybertext Yearbook 2000. According to Robert Coover, if you are looking for "serious" hypertext you should visit Eastgate.com. While, of course, "seriousness" is hard to define, we can at least imagine what we are not going to find in these texts. We are not probably going to find princesses in distress, trolls and space ships with big laser guns. So, where should we go if we are looking for "serious" computer games? As far as we know, nowhere. The reason is simple: there is an absolute lack of "seriousness" in the computer game industry. Currently, videogames are closer to Tolkien than to Chekhov; they show more influence from George Lucas rather than from François Truffaut. The reasons are probably mainly economical. The industry targets male teenagers and children and everybody else either adapts to that content or looks for another form of entertainment. However, we do not believe that the current lack of mature, intellectual content is just due to marketing reasons. As we are going to explore in this paper, current computer game design conventions have structural characteristics that prevent them to deal with "serious" content. We will also suggest different strategies for future designers in order to overcome some of these problematic issues. For the sake of our exposition, we will use the Holocaust as an example of "serious" topic, because it is usually treated with a mature approach, even if crafting a comedy, as Roberto Benigni recently did in his film "Life is Beautiful". -

Course Outline 3/23/2018 1

5055 Santa Teresa Blvd Gilroy, CA 95023 Course Outline COURSE: HUM 6 DIVISION: 10 ALSO LISTED AS: TERM EFFECTIVE: Fall 2018 CURRICULUM APPROVAL DATE: 03/12/2018 SHORT TITLE: CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA LONG TITLE: Contemporary World Cinema Units Number of Weeks Contact Hours/Week Total Contact Hours 3 18 Lecture: 3 Lecture: 54 Lab: 0 Lab: 0 Other: 0 Other: 0 Total: 3 Total: 54 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class introduces contemporary foreign cinema and includes the examination of genres, themes, and styles. Emphasis is placed on cultural, economic, and political influences as artistically determining factors. Film and cultural theories such as national cinemas, colonialism, and orientalism will be introduced. The class will survey the significant developments in narrative film outside Hollywood. Differing international contexts, theoretical movements, technological innovations, and major directors are studied. The class offers a global, historical overview of narrative content and structure, production techniques, audience, and distribution. Students screen a variety of rare and popular films, focusing on the artistic, historical, social, and cultural contexts of film production. Students develop critical thinking skills and address issues of popular culture, including race, class gender, and equity. PREREQUISITES: COREQUISITES: CREDIT STATUS: D - Credit - Degree Applicable GRADING MODES L - Standard Letter Grade REPEATABILITY: N - Course may not be repeated SCHEDULE TYPES: 02 - Lecture and/or discussion STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Demonstrate the recognition and use of the basic technical and critical vocabulary of motion pictures. 3/23/2018 1 Measure of assessment: Written paper, written exams. Year assessed, or planned year of assessment: 2013 2. Identify the major theories of film interpretation. -

La Tigre E La Neve Motivo Di Sorgere Ed Il Mondo Di Continuare a Girare”

Cineforum G. Verdi 31°anno 12° film 14 - 15 – 16 – 17 dicembre 2005 [email protected] quale…” il sole non avrebbe più La tigre e la neve motivo di sorgere ed il mondo di continuare a girare”. La poesia quindi come principale mezzo di CAST TECNICO ARTISTICO sopravvivenza contro la miseria Regia: Roberto Benigni morale che ci circonda, ma anche Sceneggiatura: Vincenzo Cerami, come possibilità di un’identità Roberto Benigni diversa, di uno stare al mondo per Fotografia: Fabio Cianchetti trasmettere ad altri il senso del Scenografia: Maurizio Sabatini proprio sentire e rafforzare, Costumi: Louise Stjernsward attraverso l’arte, una comune Musica: Tom Waits, Nicola Piovani dispetto della sua crudeltà, di sensibilità umana, capace di Montaggio: Massimo Fiocchi inneggiare al potere del cuore contro oltrepassare le barriere religiose e Prodotto da: Nicoletta Braschi per ogni ostacolo, di incantarsi di fronte linguistiche. In questo senso Melampo alla bellezza. E' sinceramente (Italia, 2005) tornano in mente le parole, convinto, Benigni, del ruolo salvifico semplici e sacrosante, con cui Durata: 118' della poesia. Lo si scorge più volte nel Distribuzione cinematografica: 01 Nicole Kidman, in una notte degli Distribution film: quando Attilio spiega alle sue Oscar, ringraziò il pubblico:: “Molti ci figlie l'importanza di saper descrivere i chiedono se sia giusto che noi PERSONAGGI E INTERPRETI sentimenti, o quando tiene una siamo qui a festeggiare mentre i fantastica lezione ai suoi studenti che nostri soldati sono appena stati Attilio De Giovanni: Roberto Benigni riecheggia quelle di Robin Williams mandati in Iraq. E’ giusto? Si, Vittoria: Nicoletta Braschi nell' Attimo fuggente. O ancora perché l’Arte è importante. -

The Last Laugh

THE LAST LAUGH A Tangerine Entertainment Production A film by Ferne Pearlstein Featuring: Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Sarah Silverman, Robert Clary, Rob Reiner, Susie Essman, Harry Shearer, Jeffrey Ross, Alan Zweibel, Gilbert Gottfried, Judy Gold, Larry Charles, David Steinberg, Abraham Foxman, Lisa Lampanelli, David Cross, Roz Weinman, Klara Firestone, Elly Gross, Deb Filler, Etgar Keret, Shalom Auslander, Jake Ehrenreich, Hanala Sagal and Renee Firestone Directed, Photographed and Edited by: Ferne Pearlstein Written by: Ferne Pearlstein and Robert Edwards Produced by: Ferne Pearlstein and Robert Edwards, Amy Hobby and Anne Hubbell, Jan Warner 2016 / USA / Color / Documentary / 85 minutes / English For clips, images, and press materials, please visit our DropBox: http://bit.ly/1V7DYcq U.S. Sales Contacts Publicity Contacts [email protected] / 212 625-1410 [email protected] Dan Braun / Submarine Janice Roland / Falco Ink Int’l Sales Contacts [email protected] [email protected] / 212 625-1410 Shannon Treusch / Falco Ink Amy Hobby / Tangerine Entertainment THE LAST LAUGH “The Holocaust itself is not funny. There's nothing funny about it. But survival, and what it takes to survive, there can be humor in that.” -Rob Reiner, Director “I am…privy to many of the films that are released on a yearly basis about the Holocaust. I cannot think of one project that has taken the approach of THE LAST LAUGH. THE LAST LAUGH dispels the notion that there is nothing new to say or to reveal on the subject because this aspect of survival is one that very few have explored in print and no one that I know of has examined in a feature documentary.” -Richard Tank, Executive Director at the Simon Wiesenthal Center SHORT SYNOPSIS THE LAST LAUGH is a feature documentary about what is taboo for humor, seen through the lens of the Holocaust and other seemingly off-limits topics, in a society that prizes free speech. -

92ND ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® SIDEBARS (Revised)

92ND ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® SIDEBARS (revised) A record 64 women were nominated, one third of this year’s nominees. Emma Tillinger Koskoff (Joker, The Irishman) and David Heyman (Marriage Story, Once upon a Time...in Hollywood) are the sixth and seventh producers to have two films nominated for Best Picture in the same year (since 1951 when individual producers first became eligible as nominees in the category). Previous producers were Francis Ford Coppola and Fred Roos (1974), Scott Rudin (2010), Megan Ellison (2013), and Steve Golin (2015). The Best Picture category expanded from five to up to ten films with the 2009 Awards year. Parasite is the eleventh non-English language film nominated for Best Picture and the sixth to be nominated for both International Feature Film (formerly Foreign Language Film) and Best Picture in the same year. Each of the previous five (Z, 1969; Life Is Beautiful, 1998; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, 2000; Amour, 2012; Roma, 2018) won for Foreign Language Film but not Best Picture. In April 2019, the Academy’s Board of Governors voted to rename the Foreign Language Film category to International Feature Film. With his ninth Directing nomination, Martin Scorsese is the most-nominated living director. Only William Wyler has more nominations in the category, with a total of 12. In the acting categories, five individuals are first-time nominees (Antonio Banderas, Cynthia Erivo, Scarlett Johansson, Florence Pugh, Jonathan Pryce). Eight of the nominees are previous acting winners (Kathy Bates, Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks, Anthony Hopkins, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, Charlize Theron, Renée Zellweger). Adam Driver is the only nominee who was also nominated for acting last year. -

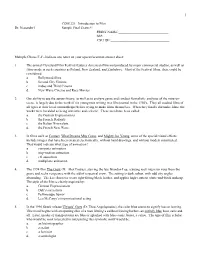

COM 221: Introduction to Film Dr. Neuendorf Sample Final Exam #1 PRINT NAME: SS

1 COM 221: Introduction to Film Dr. Neuendorf Sample Final Exam #1 PRINT NAME:_____________________________ SS#:______________________________________ CSU ID#:__________________________________ Multiple Choice/T-F--Indicate one letter on your opscan/scantron answer sheet: 1. The annual Cleveland Film Festival features American films not produced by major commercial studios, as well as films made in such countries as Poland, New Zealand, and Zimbabwe. Most of the Festival films, then, could be considered: a. Bollywood films b. Second City Cinema c. indies and Third Cinema d. New Wave Cinema and Race Movies 2. Our ability to use the auteur theory, as well as to analyze genre and conduct formalistic analyses of the mise-en- scene, is largely due to the work of six young men writing in a film journal in the 1950's. They all studied films of all types at their local cinematheque before trying to make films themselves. When they finally did make films, the works were heralded as being inventive and eclectic. These men have been called: a. the German Expressionists b. the French Dadaists c. the Italian Neorealists d. the French New Wave 3. In films such as Contact, What Dreams May Come, and Mighty Joe Young, some of the special visual effects include images that have been created electronically, without hand drawings, and without models constructed. That would indicate what type of animation? a. computer animation b. stop-motion animation c. cel animation d. multiplane animation 4. The 1994 film The Crow (D: Alex Proyas), starring the late Brandon Lee, a young rock musician rises from the grave and seeks vengeance with the aid of a spectral crow. -

Universidade Federal Do Ceará Seguindo Pinocchio

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ESTRANGEIRAS PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS DE TRADUÇÃO SIMONE LOPES DE ALMEIDA NUNES SEGUINDO PINOCCHIO: A AMBIENTAÇÃO, O FEMININO E A FUGA NA OBRA FÍLMICA DE ROBERTO BENIGNI COMO ELEMENTOS DE RESSIGNIFICAÇÃO DA OBRA LITERÁRIA DE CARLO COLLODI FORTALEZA 2016 SIMONE LOPES DE ALMEIDA NUNES SEGUINDO PINOCCHIO: A AMBIENTAÇÃO, O FEMININO E A FUGA NA OBRA FÍLMICA DE ROBERTO BENIGNI COMO ELEMENTOS DE RESSIGNIFICAÇÃO DA OBRA LITERÁRIA DE CARLO COLLODI Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Estudos de Tradução. Área de concentração: Tradução Intersemiótica. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Yuri Brunello FORTALEZA 2016 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Universidade Federal do Ceará Biblioteca Universitária Gerada automaticamente pelo módulo Catalog, mediante os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) N928s Nunes, Simone Lopes de Almeida. Seguindo Pinocchio : a ambientação, o feminino e a fuga na obra fílmica de Roberto Benigni como elementos de ressignificação da obra literária de Carlo Collodi / Simone Lopes de Almeida Nunes. – 2016. 163 f. : il. color. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Centro de Humanidades, Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Tradução, Fortaleza, 2016. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Yuri Brunello. 1. Pinocchio. 2. Ressignificação. 3. Adaptação fílmica. 4. Realístico. I. Título. CDD 418.02 SIMONE LOPES DE ALMEIDA NUNES SEGUINDO PINOCCHIO: A AMBIENTAÇÃO, O FEMININO E A FUGA NA OBRA FÍLMICA DE ROBERTO BENIGNI COMO ELEMENTOS DE RESSIGNIFICAÇÃO DA OBRA LITERÁRIA DE CARLO COLLODI Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Estudos de Tradução. -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015 General Knowledge 1 The biographical drama Straight Outta Compton, released this Friday, is an account of the rise and fall of which Los Angeles hip hop act? 2 Only two films have ever won both the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Picture. Name them. 3 Which director links the films Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News & As Good as it Gets, as well as TV show The Simpsons? 4 Which Woody Allen film won the 1978 BAFTA Award for Best Film, beating fellow nominees Rocky, Net- work and A Bridge Too Far? 5 The legendary Robert Altman was awarded a BFI Fellowship in 1991; but which British director of films including Reach for the Sky, Educating Rita and The Spy Who Loved Me was also honoured that year? Italian Film 1 Name the Italian director of films including 1948’s The Bicycle Thieves and 1961’s Two Women. 2 Anna Magnani became the first Italian woman to win the Best Actress Academy Award for her perfor- mance as Serafina in which 1955 Tennessee Williams adaptation? 3 Name the genre of Italian horror, popular during the 1960s and ‘70s, which includes films such as Suspiria, Black Sunday and Castle of Blood. 4 Name Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 debut feature film, which was based on his previous work as a novelist. 5 Who directed and starred in the 1997 Italian film Life is Beautiful, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, amongst other honours. -

The Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish

The Parkes Institute for the study of Jewish/non-Jewish relations Annual Review 2015 - 2016 In summer 2016, Kathrin Pieren and Tony Kushner organised the first Parkes International Workshop on 1 Jewish Heritage, generously supported by the Rothschild Foundation Europe (Hanadiv). See page 13 for the full report. Here, the value of the hand-in-hand of museum work and academic research was illustrated by the excellent talk by Dr Alla Sokolova, Curator at the State Museum of the History Religions in St Petersburg and Lecturer at the European University of St Petersburg. She presented the results of a field study related to an exhibition of Jewish family heirlooms that she organised a few years ago. The exhibits, many of them everyday items such as photographs or pieces of clothing, were charged with meaning by the lenders, Jewish individuals, some of whom are shown in the pictures on this page. 3 3 4 7 2 1. Natalia F. shows her 2 father’s tallit 2. Boris F. with a Kiddush glass 3. Ulia O. with candlesticks and a wine decanter 4. The Holy Union Temple in Bucharest 5. Mrs. L. during the interview 6. Mr Futeran at his home in Tomash’pol 7. INGER Hersh (cover), KHASHCHEVATSKY M. (text), In Shveren Gang, Kharkov, 1929 5 In this review Report of the Director of the Parkes Institute, Professor Joachim Schlör 4 The Parkes Jubilee Celebrations 7 In memoriam David Cesarani (1956 to 2015) 8 Parkes Institute Outreach Report 2015-16 10 Conferences, Workshops, Lecturers and Seminars 13 Journals of the Parkes Institute 16 Development 17 Internationalisation