Restoring the Navigli in Milan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arena 2015 93° Festival Lirico

ARENA 2015 93° FESTIVAL LIRICO Garda Lake Regular and private excursions GARDA LAKE GARDA ISLAND Isola del Garda is a place of rare and special beauty, REGULAR EXCURSIONS Tour around the lake. Tour surrounded by the clear waters of the lake: a by coach along the romantic Gardesana, one of the picturesque rock that has welcomed ancient people most beautiful roads in Europe with its particular from the Romans to the Longobards. At long last it is vegetation like olive trees, cypresses and flowers with now possible to admire its trasures: the neogothic Venetian villa, the artificial caves, but above all the an extraordinary beauty. Stops on the most beautiful spots. A visit to several picturesque villages to see amazing gardens which date back to the 1880. monuments dating from the period of Roman, Scaliger, Venetian and Austrian possessors. A part of the lake will be crossed by ferryboat. PRIVATE EXCURSIONS An amazing itinerary on the largest lake in Italy to visit its beatiful villages, island and to taste typical wines and products. Pickup at the hotel with the hostess to go to Garda for a quick visit of the village. Transfer by private roofed motorboat to Punta San Vigilio and Isola del Garda. Visit of the beautiful island. Isola del Garda is a place of rare and special beauty. A precious jewel, plenty of history, memories and legends. Historical italian Gardens Experience Guerrieri Rizzardi Garden (Bardolino Giardino Giusti (Verona) Garda lake) In Verona you will find one of Italy’s finest Renaissance The estate in Bardolino, on Lake Garda, dates back to gardens: Giardino Giusti. -

Vertical Facility List

Facility List The Walt Disney Company is committed to fostering safe, inclusive and respectful workplaces wherever Disney-branded products are manufactured. Numerous measures in support of this commitment are in place, including increased transparency. To that end, we have published this list of the roughly 7,600 facilities in over 70 countries that manufacture Disney-branded products sold, distributed or used in our own retail businesses such as The Disney Stores and Theme Parks, as well as those used in our internal operations. Our goal in releasing this information is to foster collaboration with industry peers, governments, non- governmental organizations and others interested in improving working conditions. Under our International Labor Standards (ILS) Program, facilities that manufacture products or components incorporating Disney intellectual properties must be declared to Disney and receive prior authorization to manufacture. The list below includes the names and addresses of facilities disclosed to us by vendors under the requirements of Disney’s ILS Program for our vertical business, which includes our own retail businesses and internal operations. The list does not include the facilities used only by licensees of The Walt Disney Company or its affiliates that source, manufacture and sell consumer products by and through independent entities. Disney’s vertical business comprises a wide range of product categories including apparel, toys, electronics, food, home goods, personal care, books and others. As a result, the number of facilities involved in the production of Disney-branded products may be larger than for companies that operate in only one or a limited number of product categories. In addition, because we require vendors to disclose any facility where Disney intellectual property is present as part of the manufacturing process, the list includes facilities that may extend beyond finished goods manufacturers or final assembly locations. -

5. Leasure Day 3-9 July

THINGS TO DO & SEE IN MILAN Milan Cathedral Milan Cathedral (Italian: Duomo di Milano) is the cathedral church of Milan, Italy. Dedicated to St Mary of the Nativity (Santa Maria Nascente), it is the seat of the Archbishop of Milan, currently Cardinal Angelo Scola. The Gothic cathedral took nearly six centuries to complete. It is the largest church in Italy (the larger St. Peter's Basilica is in the State of Vatican City) and the fifth largest in the world. Milan Historical Center Underground Line M1 and M3 stop Duomo Everyday from 8.00 to 21.00 For info and reservations www.duomomilano.it Santa Maria delle Grazie "Holy Mary of Grace“ (Italian: Santa Maria delle Grazie) is a church and Dominican convent in Milan, northern Italy, included in the UNESCO World Heritage sites list. The church contains the mural of ”The Last Supper" by Leonardo da Vinci, which is in the refectory of the convent. Piazza Santa Maria delle Grazie Underground Line 1: Cadorna or Conciliazione Underground Line 2: Cadorna or Sant’Ambrogio Tue – Sun 8:15 – 19:15. Last ingress at 18:45. Max. 25 people every 15 minutes. For info and reservations www.vivaticket.it Pinacoteca di Brera The Pinacoteca di Brera ("Brera Art Gallery") is the main public gallery for paintings in Milan, Italy. It contains one of the foremost collections of Italian paintings, an outgrowth of the cultural program of the Brera Academy, which shares the site in the Palazzo Brera. The Palazzo Brera owes its name to the Germanic braida, indicating a grassy opening in the city structure: compare the Bra of Verona. -

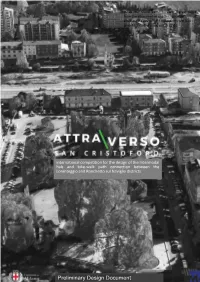

Preliminary Design Document

[Grab your reader’s attention with a great quote from the document or use this space to emphasize a key point. To place this text box anywhere on the page, just drag it.] international competition for the design of the Intermodal hub and bike-walk path connection between the Lorenteggio and Ronchetto sul Naviglio districts 2 | Municipality of Milan Preliminary Design Document 2| Municipality of Milan Preliminary Design 2 Document International design competition for the new cycling- pedestrian connecting path between Lorenteggio and Ronchetto sul Naviglio December 2018 Municipality of Milan |3 4 | Municipality of Milan INDEX INTRODUCTION 1. COMPETITION SCOPE [1.1] General theme and objectives of the competition 1.2] Identification of the areas of intervention [1.3] Specific objectives for each area 2. GENERAL OVERVIEW [2.1] The Lorenteggio and Giambellino districts [2.2] Naviglio Grande [2.3] Ronchetto sul Naviglio and the Parco Agricolo Sud 3. FUTURE SCENARIOS: THE CONTEXT DESIGN MEDIUM [3.1] The vision for Milan 2030 [3.2] The San Cristoforo stop [3.3] The M4 metro line [3.4] The Circle Line [3.5] Interchange and interventions on mobility 4. PROJECT THEMES [4.1] Context relationship [4.2] Urban quality [4.3] Efficiency of the intermodal exchange [4.4] The connection as an environmental infrastructure [4.5] Architectural quality, materials and finishes 5. CONSTRAINTS [5.1] Environmental constraints [5.2] Infrastructure and interference constraints 6. SUMMARY: REQUIREMENTS AND CONSTRAINTS 7. FEE CALCULATION [7.1] Financial limits to be respected [7.2] Procedure adopted for the calculation of the tender starting bid [7.3] Economic framework and calculation parameters [7.4] Economic statement of the overall service charges 8. -

Herons Round Milan '

cover_INGL 20-02-2008 10:24 Pagina 1 MILAN AND ITS PROVINCE MILAN AND ITS PROVINCE MILAN AND ITS PROVINCE HERONS ROUND MILAN ‘ This guide is part HERONS of a project that the Province of Milan is carrying out with all the main local ‘ actors in order ROUND to boost tourism in the Abbiategrasso- MILAN Magenta area. A TOURIST GUIDEBOOK A TOURIST GUIDEBOOK Abbiategrasso, Magenta, Canals and Parks cover_INGL 20-02-2008 10:24 Pagina 2 ABBIATEGRASSO MAGENTA AREA Highways Main roads Important roads Parco Lombardo della Valle del Ticino Parco Agricolo Sud Milano Places mentioned in the guidebook MILAN AND ITS PROVINCE HERONS‘ ROUND MILAN A TOURIST GUIDEBOOK Abbiategrasso, Magenta, Canals and Parks DIREZIONE CENTRALE TURISMO E AGRICOLTURA Viale Piceno 60 20129 Milano [email protected] Director of the Tourism Text by and Agricolture Department Roberto Peretta Pia Benci Art Director Tourism Department Barbara Vitale Monica Giudici Andrea Vitale Anna Zetti Editing and Layout Digital Art sas Thanks to Via Rimini, 24 - 20144 Milano Paolo Ambrosoni, Rossana Arioli, e-mail: [email protected] Maurizio Bianchi, Tiziano Binfarè, Franco Del Grandi, Raffaele Forni, Photo credits Maurizio Bianchi Piero Gabelli, Giovanna Gualeni, Toni Nicolini Vittorio Malvezzi, Alberto Marini, Massimo Pizzigoni Silva Martinis, Alessandro Mola, Romano Vitale Simone Moroni, Roberta Nencini, Archivio Digital Art Gianni Oggioni, Dario Oliverio, Daniela Paci, Giovanni Pioltini, Maps Elisabetta Porro, Fabrizio Scelsi, LS International Margherita Scirpa, Danilo Taglietti, Illustrations Giuseppe Zanoni … Adelchi Galloni Our thanks also go to all those who have been collaborating English Version with us for months Studio Associato ScriptoriA to reach this goal. -

5. Leasure Day 3-9 July

THINGS TO DO & SEE IN MILAN Milan Cathedral Milan Cathedral (Italian: Duomo di Milano) is the cathedral church of Milan, Italy. Dedicated to St Mary of the Nativity (Santa Maria Nascente), it is the seat of the Archbishop of Milan, currently Cardinal Angelo Scola. The Gothic cathedral took nearly six centuries to complete. It is the largest church in Italy (the larger St. Peter's Basilica is in the State of Vatican City) and the fifth largest in the world. Milan Historical Center Underground Line M1 and M3 stop Duomo Everyday from 8.00 to 21.00 For info and reservations www.duomomilano.it Santa Maria delle Grazie "Holy Mary of Grace“ (Italian: Santa Maria delle Grazie) is a church and Dominican convent in Milan, northern Italy, included in the UNESCO World Heritage sites list. The church contains the mural of ”The Last Supper" by Leonardo da Vinci, which is in the refectory of the convent. Piazza Santa Maria delle Grazie Underground Line 1: Cadorna or Conciliazione Underground Line 2: Cadorna or Sant’Ambrogio Tue – Sun 8:15 – 19:15. Last ingress at 18:45. Max. 25 people every 15 minutes. For info and reservations www.vivaticket.it Pinacoteca di Brera The Pinacoteca di Brera ("Brera Art Gallery") is the main public gallery for paintings in Milan, Italy. It contains one of the foremost collections of Italian paintings, an outgrowth of the cultural program of the Brera Academy, which shares the site in the Palazzo Brera. The Palazzo Brera owes its name to the Germanic braida, indicating a grassy opening in the city structure: compare the Bra of Verona. -

Ref. 1911 – VILLA SUL NAVIGLIO € 3.900.000

Ref. 1911 – VILLA SUL NAVIGLIO € 3.900.000 Milan – Milan – Lombardy www.romolini.co.uk/en/1911 Interiors Bedrooms Bathrooms Swimming pool 660 sqm 4 6 4 × 3 m Exteriors 255 sqm, including courtyards and terraces Along the Naviglio Pavese, in a very convenient location in the city of Milan, this luxury villa offers three residential units for a total of 660 sqm, 4 bedrooms and 6 bathrooms. Two nice gardened terraces with summer kitchen and a central courtyard with heated pool offer pleasant outdoor spaces to relax with friends. © Agenzia Romolini Immobiliare s.r.l. Via Trieste n. 10/c, 52031 Anghiari (AR) Italy Tel: +39 0575 788 948 – Fax: +39 0575 786 928 – Mail: [email protected] REFERENCE #: 1911 – VILLA SUL NAVIGLIO TYPE: luxury villa with guesthouse and pool CONDITIONS: luxury finishes LOCATION: city, along the Naviglio Pavese MUNICIPALITY: Milan PROVINCE: Milan REGION: Lombardy INTERIORS: 660 square meters (7,100 square feet) TOTAL ROOMS: 15 BEDROOMS: 4 BATHROOMS: 6 MAIN FEATURES: terraces, ample living rooms, fireplaces, wooden beams, parquet floors, heated pool, summer kitchen, glass-covered veranda, ample paved courtyard with portico EXTERIORS: 255 square meters (0.06 acres) GARDEN: yes, well-maintained on the terraces ANNEXES: guesthouse ACCESS: excellent SWIMMING POOL: 4 × 3 m ELECTRICITY: already connected WATER SUPPLY: mains water TELEPHONE: already connected ADSL: yes GAS: municipal network HEATING SYSTEM: radiators + air conditioning Historic center of Milan (13km; 20’), Pavia (39km; 35’), Lodi (42km; 40’), Bergamo (60km; 1h 5’), Como (61km; 55’), Crema (61km; 50’), Desenzano del Garda (137km; 1h 30’), Genoa (141km; 1h 40’), Turin (152km; 1h 55’) Milano Linate (13km; 20’), Bergamo Caravaggio (60km; 55’), Milano Malpensa (61km; 45’), Parma Verdi (130km; 1h 20’), Torino Pertini (154km; 1h 30’), Verona Catullo (167km; 1h 45’), Bologna Marconi (212km; 2h), Venezia Marco Polo (287km; 2h 55’) © Agenzia Romolini Immobiliare s.r.l. -

State of Art Metropolitan City of Milan

State of the Art of Area of Metropolitan City of Milan Authors Edo Brichetti – External expert of Metropolitan City of Milan Dario Parravicini – Metropolitan City of Milan Carla Bottazzi – Metropolitan City of Milan Katia Rossetto – Metropolitan City of Milan December, 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 Methodology 2. The regional context 2.1 The geo-institutional context 2.1.1 About the territory 2.1.2 About the culture 2.1.3 About the economic system 2.1.4 Description of Metropolitan City of Milan 2.1.5 About the water system 2.1.5.1 About the water system of the Navigli (historic canals) 2.2 The socio –economic context 2.2.1 Demographic statistics 2.2.2 Labour market conditions and its change in the past 6 years 2.2.3 Economic accounts and their change in the past 10 years 2.2.4 Structural business statistics and its change in the past 10 years 2.2.5 The Metropolitan City of Milan firms by sector and geographical area 2015 2.2.6 The socio economic context about the water system of Navigli 2.2.6.1 About hospitality in the Navigli area 2.2.6.2 About agriculture in the Navigli area 2.2.6.3 Overview of environment, landscape and culture in the Navigli area 2.3 Governance 2.3.1 Regional Government 2.3.2 MCM Government 2 2.3.3 Spatial regional-economic waterway management 2.4 Tourism and Culture 2.4.1 Natural heritage sites 2.4.1.1 Natural vacation in Lombardy 2.4.1.2 Lake vacation in Lombardy 2.4.1.3 Mountain vacation in Lombardy 2.4.2 Water system and water network 2.4.2.1 About the recreational water network 2.4.2.2 Water system and tourism 2.4.2.3 Watersystem: monitoring system and the status of surface waters 2.4.2.4 The water resources sector of the Metropolitan City of Milan 2.4.3 Cultural heritage sites 2.4.3.1 Unesco sites in Lombardy 2.4.3.2 Events in Lombardy 2.4.3.3 Monuments and landscape sceneries in Lombardy 2.4.4 Characteristics of tourism and culture 2.5 Strengths and weaknesses of tourism, heritage management and culture 3. -

WM April 2013.Pdf

APRIL APRIL 2013 ALL YOU CAN DO THE COMplETE GUIDE TO GO® IN THIS CITY Milan ® wheremilan.com WELCOME SHOPPING, DINING and ENTERTAINMENT DON’T MISS TO THE WHAT’S neW IN THE CITY CONTAINS GENERAL AND THEMATIC MAPS OF MILAN ADVENTURE WITH AFRICA’S MAKERS,ADVENT THINKERSUR EAND WITH DREAMERS AFRICA’S MAKEForget whatRS, you think TH you knowIN aboutKE Africa,RS the world’s AN D DREAMERS second-largest continent is journeying to new frontiers. Come face to face with this inspiring vision as you adventure with la Rinascente into an Afrofuturist design culture. WELCOME COME IN-STORE AND EXPLORE THE AFROFUTURE MilanoTO Piazza THEDuomo. Design Supermarket. OPENING HOURS: Monday - Friday 09:30-22:00 | Saturday - Sunday 09:30-23:00 Africa Lab programme curated by Beatrice Galilee. Pick up a free guide in-store. ADVENTURE WITH AFRICA’S MAKERS, THINKERS AND DREAMERS afrofuture.com #afrofuture MILANO PIAZZA DUOMO ENJOY YOUR SHOPPING font cohin bold GIVE THIS COUPON AT LA RINASCENTE STORE IN Recommendedlogo nuovo_35x35.pdf 7-05-2008 by 21:36:47 WHERE MILAN PROJECT MILAN YOU’LL GET 10%* OFF ON YOUR PURCHASES. IS ENDORSED BY * Exclusively for foreignTOWARDS individual customers upon presentation of a valid foreign passport. Valid except for regional restriction Clefs d’Or Clefs d’Or regulations and only on brands which support the initiative. The discount cannot be combined with other promotions and Clefs d’Or st “ does not apply on cafeterias and restaurants on the 7th floor (valid on food market purchases). Valid till July 31 , 2013. Le ro” Chiavi d’O -

State of the Art MCM 30 12 2016 EB

State of the Art of Area of Metropolitan City of Milan Authors Edo Bricchetti – External expert of Metropolitan City of Milan Dario Parravicini – Metropolitan City of Milan Carla Bottazzi – Metropolitan City of Milan Katia Rossetto – Metropolitan City of Milan December, 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 Methodology 2. The regional context 2.1 The geo-institutional context 2.1.1 About the territory 2.1.2 About the culture 2.1.3 About the economic system 2.1.4 Description of Metropolitan City of Milan 2.1.5 About the water system 2.1.5.1 About the water system of the Navigli (historic canals) 2.2 The socio –economic context 2.2.1 Demographic statistics 2.2.2 Labour market conditions and its change in the past 6 years 2.2.3 Economic accounts and their change in the past 10 years 2.2.4 Structural business statistics and its change in the past 10 years 2.2.5 The Metropolitan City of Milan firms by sector and geographical area 2015 2.2.6 The socio economic context about the water system of Navigli 2.2.6.1 About hospitality in the Navigli area 2.2.6.2 About agriculture in the Navigli area 2.2.6.3 Overview of environment, landscape and culture in the Navigli area 2.3 Governance 2.3.1 Regional Government 2.3.2 MCM Government 2 2.3.3 Spatial regional-economic waterway management 2.4 Tourism and Culture 2.4.1 Natural heritage sites 2.4.1.1 Natural vacation in Lombardy 2.4.1.2 Lake vacation in Lombardy 2.4.1.3 Mountain vacation in Lombardy 2.4.2 Water system and water network 2.4.2.1 About the recreational water network 2.4.2.2 Water system and tourism 2.4.2.3 Watersystem: monitoring system and the status of surface waters 2.4.2.4 The water resources sector of the Metropolitan City of Milan 2.4.3 Cultural heritage sites 2.4.3.1 Unesco sites in Lombardy 2.4.3.2 Events in Lombardy 2.4.3.3 Monuments and landscape sceneries in Lombardy 2.4.4 Characteristics of tourism and culture 2.5 Strengths and weaknesses of tourism, heritage management and culture 3. -

2. Drinking Water Supply from Groundwater 20 3

blue book water protection and management in Lombardy blue book water protection and management in Lombardy Blue Book – Protection and Management of waters in Lombardy 2008 Regione Lombardia Direzione Generale Reti e Servizi di Pubblica Utilità e Sviluppo sostenibile Project leader and coordinator: Nadia Chinaglia Working group DG Reti e Servizi di Pubblica Utilità e Sviluppo Sostenibile: Nadia Andreani, Maria Teresa Babuscio, Rebecca Brumana, Silvio Carta, Carlo Enrico Cassani, Silvia Castelli, Roberto Cerretti, Nadia Chinaglia, Viviane Iacone, Giovanni Mancini, Marco Nicolini, Laura Rossi, Noemi Salvoni, Giliola Verza. DG Agricoltura: Sauro Coffani, Andrea Pietro Corapi. DG Protezione Civile, Prevenzione e Polizia locale: Maurizio Molari. DG Territorio e Urbanistica: Marina Credali, Raffaele Occhi. DG Infrastrutture e Trasporti: Egle Freppa. ARPA: Roberto Serra, Enrico Zini. IREALP: Daniele Magni. Photos Cover: C.Bollini, C. Bollini, Nadia Chinaglia © Nadia Chinaglia: photos pages 7, 15, 16, 18, 22, 30, 33, 38, 45, 48, 55, 57, 62, 63, 67, 70, 73, 74, 76, 78 © C. Bollini: photos pages 19, 35, 39, 52, 53, 56, 59, 69, 77 © Marco Nicolini: photos pages 17, 47, 51 © Alberto Maffiotti: photos pages 29, 71 © Carmelo di Mauro: photo page 8 © Raffaele Occhi: photo page 26 © Coordinamento Turistico lago di Como – foto di Alberto Locatelli: photo page 60 © Provincia di Varese – settore Marketing Territoriale e Rapporti Istituzionali: photo page 65 Graphic design and printing: Morbegno (SO) Indice 1 - Water protection 9 Environmental quality of surface water 10 1. Environmental quality of surface water 10 1.1 Watercourses 11 1.2 Lakes 13 1.3 Suitability for fish life 14 2. Groundwater 15 Drinking water 18 1. -

Analysis of Groundwater Environment Change in the Milan Metropolitan Area by Hydrostratigraphic, Groundwater Quality and Flow Modeling

SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO-BICOCCA Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences PhD program in Chemical, Geological, and Environmental Sciences XXX Cycle Geological Sciences Curriculum Analysis of groundwater environment change in the Milan Metropolitan area by hydrostratigraphic, groundwater quality and flow modeling De Caro Mattia Number 718931 Tutor: Prof. Crosta Giovanni Battista Coordinator: Prof. Frezzotti Maria Luce ACADEMIC YEAR 2017/2018 Abstract Groundwater plays a fundamental role in shaping the economic and the social health of many urban areas. Due to its relatively low-cost and generally high quality, groundwater has been widely exploited for private domestic, irrigational, and industrial use. However, industrial use has decreased dramatically in the last few decades leading to a groundwater level rise causing geotechnical and environmental problems. Many urban areas are currently suffering this situation with consequent concerns about damage to subsurface engineering structures, inundation of subsurface facilities, and the mobilization of contaminants. As results, in recent years it has been recognised that urban groundwater is a potentially valuable resource due to problems associated with its under exploitation. The objective of this thesis is to tackle four main issues: (i) developing a robust hydro-stratigraphic model and providing a comprehensive hydraulic parametrization of glaciofluvial aquifers, (ii) providing a hydrogeochemical characterization and assessing the groundwater quality status relative to baseline conditions in a complex framework (i.e. urban), (iii) monitoring groundwater level and understanding the spatial variability of groundwater recharge (i.e. effective rainfall recharge and canal infiltration) to unconfined aquifer in urban areas, and (iv) developing both a regional and an urban scale groundwater flow model for simulating future withdrawals and climate (i.e.