2. Drinking Water Supply from Groundwater 20 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lambro River Valley Greenways System Alessandro Toccolini∗, Natalia Fumagalli, Giulio Senes

Landscape and Urban Planning 76 (2006) 98–111 Greenways planning in Italy: the Lambro River Valley Greenways System Alessandro Toccolini∗, Natalia Fumagalli, Giulio Senes Institute of Agricultural Engineering, University of Milan, Via Celoria 2, 20133 Milano, Italy Available online 11 November 2004 Abstract The greenways movement in Europe developed differently to its counterpart in the USA, influenced by geographical, economic and cultural differences as well as differences in social and urban development. Europe has seen a discontinuous and fragmented process, diversified in the various countries. The explosion of the greenway concept in Europe is a very recent phenomenon: the European Greenways Association and the Italian Greenways Association both date back only as far as 1998. Clearly, before this date the European countries did see a degree of activity both cultural and operational, but it is equally clear that there was a lack of commonality. Specifically, greenway planning in Italy while on the one hand work has been underway on green trails for many years, on the other there is a clear lack of methodology that allows for the planning of a broader network. This paper has two objectives; firstly to define a methodology useful for greenways planning in Italy at regional level, and secondly, to demonstrate the application of this methodology to a case study. The methodology adopted derives from an approach to planning inspired principally by the work of Ian McHarg and Julius Fabos and already applied by the authors to protected areas in Italy. The methodology is structured in four phases: analysis of the landscape resources, the existing green trail and historical route networks; assessment of each element; composite assessment; and definition of the Greenways Plan. -

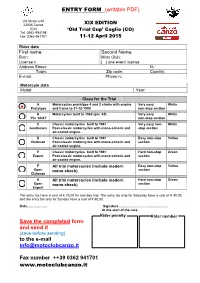

ENTRY FORM (Writable PDF) Save the Completed

ENTRY FORM (writable PDF) Via Meda n.40 22035 Canzo XIX EDITION (Co) ‘Old Trial Cup’ Caglio (CO) Tel. 0362-994198 Fax. 0362-941701 11-12 April 2015 Rider data First name: Second Name: Born: Moto Club: License n. [ ] one event license Address Street: N.: Town: Zip code: Country: E-mail: Phone n.: Motorcyle data Model: Year: Class for the Trial A Motorcycles prototype 4 and 2 stroke with engine Very easy White Prototype and frame to 31-12-1990 non-stop section B Motorcycles built to 1965 (pre ’65) Very easy White Pre ‘65/4T non-stop section C Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Ver y easy non - White Gentlemen Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and stop section air-cooled engine. D Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Easy non -stop Yellow Clubman Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. E Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Hard non -stop Green Expert Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. F All trial motorcycles (include modern Easy non -stop Yellow Open mono shock) section Clubman G All trial motorcycles (include modern Hard non -stop Green Open mono shock) section Expert The entry tax have a cost of € 75,00 for two day trial. The entry tax only for Saturday have a cost of € 40,00 and the entry tax only for Sunday have a cost of € 40,00. Data……………… Signature……………………………………… At the start of the race Rider penalty Rider number Save the completed form and send it (save before sending) to the e-mail [email protected] Fax number ++39 0362 941701 www.motoclubcanzo.it How reach the trial in Caglio (CO) From Turin : Highway Turin-Milan following on the west ring of Milan to direction Venice and exit to Cinisello Balsamo toward the highway Milan-Lecco direction Lecco. -

Lago Maggiore - Passo Dello Stelvio Tour Lago Maggiore

TOUR LAGO MAGGIORE - PASSO DELLO STELVIO TOUR LAGO MAGGIORE PASSO DELLO STELVIO TOUR LAGO MAGGIORE PASSO DELLO STELVIO PROGRAMMA PROGRAM 1° GIORNO: Arrivo e sistemazione in Hotel 1° DAY: Arrival and accomodation 2° GIORNO: 1° Tappa RANCO - ORTA S. GIULIO 2° DAY: 1° Stage RANCO - ORTA S. GIULIO 3° GIORNO: 2° Tappa RANCO - LUINO COLMEGNA 3° DAY: 2° Stage RANCO - LUINO COLMEGNA 4° GIORNO: 3° Tappa LUINO COLMEGNA - MANTELLO 4° DAY: 3° Stage LUINO COLMEGNA - MANTELLO 5° GIORNO: 4° Tappa MANTELLO - BORMIO 5° DAY: 4° Stage MANTELLO - BORMIO 6° GIORNO: 5° Tappa BORMIO - PASSO DELLO STELVIO 6° DAY: 5° Stage BORMIO - PASSO DELLO STELVIO 7° GIORNO: 6° Tappa BORMIO - PASSO GAVIA 7° DAY: 6° Stage BORMIO - PASSO GAVIA 8° GIORNO: Rientro a Milano-Malpensa 8° DAY: Back to Milano-Malpensa ST TOUR 1 DAY LAGO MAGGIORE / PASSO DELLO STELVIO FROM MALPENSA Day 1 Sunday TO RANCO PROGRAM • Arrivo all'aereoporto di Milano-Malpensa • Transfer a RANCO (VA) Hotel Belvedere (30 min.) • Accoglienza • Spuntino di benvenuto • Briefing della settimana • Fitting Bike • Cena tipica con le specialità di pesce del lago Maggiore • Arrival at Milano Malpensa Airport • Transfer (30 min.) to Hotel Belvedere in RANCO (VA) • Greeting • Welcome snack • The week’s briefing • Bike fitting • Traditional evening meal with specialities featuring fish from Lake Maggiore ST TOUR 1 Stage LAGO MAGGIORE / PASSO DELLO STELVIO FROM RANCO PLANIMETRY TO ORTA RANCO 203 mt. OSL ORTA SAN GIULIO 240 mt. OSL 95 km Average: 7% Max: 11% 780 mt Difficulty: ALTIMETRY ST TOUR 1 Stage LAGO MAGGIORE / PASSO DELLO STELVIO FROM RANCO Dal lago Maggiore al lago D’Orta TO Lake Maggiore to Lake Orta ORTA La prima tappa prevede la partenza da Ranco in direzione di Arona, in cui i primi 15 km. -

From Brunate to Monte Piatto Easy Trail Along the Mountain Side , East from Como

1 From Brunate to Monte Piatto Easy trail along the mountain side , east from Como. From Torno it is possible to get back to Como by boat all year round. ITINERARY: Brunate - Monte Piatto - Torno WALKING TIME: 2hrs 30min ASCENT: almost none DESCENT: 400m DIFFICULTY: Easy. The path is mainly flat. The last section is a stepped mule track downhill, but the first section of the path is rather rugged. Not recommended in bad weather. TRAIL SIGNS: Signs to “Montepiatto” all along the trail CONNECTIONS: To Brunate Funicular from Como, Piazza De Gasperi every 30 minutes From Torno to Como boats and buses no. C30/31/32 ROUTE: From the lakeside road Lungo Lario Trieste in Como you can reach Brunate by funicular. The tram-like vehicle shuffles between the lake and the mountain village in 8 minutes. At the top station walk down the steps to turn right along via Roma. Here you can see lots of charming buildings dating back to the early 20th century, the golden era for Brunate’s tourism, like Villa Pirotta (Federico Frigerio, 1902) or the fountain called “Tre Fontane” with a Campari advertising bas-relief of the 30es. Turn left to follow via Nidrino, and pass by the Chalet Sonzogno (1902). Do not follow via Monte Rosa but instead walk down to the sportscentre. At the end of the football pitch follow the track on the right marked as “Strada Regia.” The trail slowly works its way down to the Monti di Blevio . Ignore the “Strada Regia” which leads to Capovico but continue straight along the flat path until you reach Monti di Sorto . -

L'addio a VASCO L'uomo Che Per Tre Volte Guidò Lovere

WWWARABERARAIT COSTON BEACH WWWARABERARAIT CONCESSIONARIA MILLER REDAZIONEREDAZIONE ARABERARAITARABERARAIT DAL ACCESSORI CAMPER PREZZI FIERA TASSO ZERO NEI GIORNI DI VAL SERIANA, VAL DI SCALVE, ALTO E BASSO SEBINO, LAGO D’ENDINE, VAL CAVALLINA, BERGAMO + FORNITURE PER ASSOCIAZIONI Autorizzazione Tribunale di Bergamo: 6ZNSINHNSFQJ APERTURA Pubblicità «Araberara» PORTE APERTE Numero 8 del 3 aprile 1987 Tel. 0346/28114 Fax 0346/921252 STRAORDINARIA 9-16-23 NOVEMBRE Redazione Via S. Lucio, 37/24 - 24023 Clusone 24 Ottobre 2008 Composizione: Araberara - Clusone Tel. 0346/25949 Fax 0346/27930 DOMENICA 9-16-23 NOVEMBRE “Poste italiane Spa - Spedizione in A.P. - D.L. 353/2003 Anno XXII - n. 20 (327) - E 1,50 Stampa: C.P.Z. Costa di Mezzate (Bg) FINANZIABILI 100% (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art.1, comma 1, DCB Bergamo” Direttore responsabile: Piero Bonicelli CODICE ISSN 1723 - 1884 OMAGGIO A TUTTI I CLIENTI OTTOBRE 'JSJIJYYFLJSYJ - 1" TRA TERRA (p.b.) “Ma cos’è la destra, cos’è la sinistra?”. Come al º6}Ê personaggio di Altan, a volte mi vengono idee che non condivido. Mi preoccupo, perché ho il sospetto che mi À`ÕÀÀiʽÀ>ÀÊ E CIELO stiano asfaltando quel che resta dell’autonomia di pen- siero. Che non necessariamente deve essere “diverso” da ÃV>ÃÌV ARISTEA CANINI quello della maggioranza dei propri compaesani, quello i sono giorni che non lo rivendicano i bastian contrari di principio. Ma non mi iÊ>ÕiÌ>ÀiÊ sono come gli altri, dove convince un programma di governo che si basa sui bi- Cle cose sembrano succe- sogni indotti: prima li creano con una sapiente (?) cam- }Ê>ÕÊ dere proprio perché fanno par- pagna di omologazione e sollecitazione mediatica e poi te di una data e non viceversa, li registrano nei sondaggi, per cui fanno quello che fi n dal principio volevano fare. -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Bus LN027

Orari e mappe della linea bus LN027 LN027 Riva del Garda - Gargnano - Desenzano Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus LN027 (Riva del Garda - Gargnano - Desenzano) ha 5 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Campione: 13:30 (2) Desenzano: 05:40 - 17:10 (3) Gargnano: 12:45 (4) Gargnano: 06:45 - 15:30 (5) Riva Del Garda: 05:50 - 19:00 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus LN027 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus LN027 Direzione: Campione Orari della linea bus LN027 10 fermate Orari di partenza verso Campione: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 13:30 martedì 13:30 Riva Del Garda - Autostazione mercoledì 13:30 Riva Del Garda - Viale Canella Viale Canella, Riva del Garda giovedì 13:30 Riva Del Garda - Centrale Idroelettrica venerdì 13:30 sabato 13:30 Riva Del Garda - Strada Statale 45 domenica Non in servizio Limone - Strada Statale 45 Sentiero del Sole, Limone Sul Garda Limone - Sopino Informazioni sulla linea bus LN027 Limone - Via IV Novembre, Via Caldogno Direzione: Campione Fermate: 10 Limone - Via IV Novembre Durata del tragitto: 20 min La linea in sintesi: Riva Del Garda - Autostazione, Tremosine - Bivio Centro Riva Del Garda - Viale Canella, Riva Del Garda - Centrale Idroelettrica, Riva Del Garda - Strada Statale Tremosine - Campione 45, Limone - Strada Statale 45, Limone - Sopino, Limone - Via IV Novembre, Via Caldogno, Limone - Via IV Novembre, Tremosine - Bivio Centro, Tremosine - Campione Direzione: Desenzano Orari della linea bus LN027 57 fermate Orari di partenza -

BROCHURE INFORMATIVA COMUNE DI IDRO 0.Pdf

COMUNECOMUNE DIDI IDRO IDROIDRO Idro is ... a world waiting to be discovered In Auto come raggiungerci: Dall’Austria: Autostrada: Innsbruck - Brennero (Ita) - Bolzano - Trento (uscire dall’autostrada a Trento Nord) - Tione (seguendo per Riva fino a Le Sarche) - Lago Idro è... TRENTO km 70 MILANO km 150 d’Idro (in direzione Brescia) - Anfo - Idro. Idro un mondo da scoprire VENEZIA km 220 BRESCIA km 60 Dalla Svizzera: Autostrada: Gottardo - Bellinzona - Lugano - Chiasso (Ita) - Como MADONNA BRENNERO - Milano - Brescia (uscita dell’autostrada a Brescia Est) - Lago d’Idro (seguire le in- BOLZANO è...un mondo da scoprire DI CAMPIGLIO dicazioni per Lago di Garda - Lago d’Idro - Valle Sabbia - Madonna di Campiglio). Idro ist ... eine Welt zum entdecken Da Bologna: Autostrada: Verona - Desenzano (uscita dell’autostrada) - Salò - Tor- TRENTO is...a world waiting to be discovered mini - Lago d’Idro (seguire le indicazioni per Lago d’Idro - Valle Sabbia - Madonna di Campiglio). ist...eine Welt zum entdecken RIVA IDRO ROVERETO In Treno: Stazione di Brescia (60 km). In Autobus Lago d’Idro Da Brescia ferma a Idro (Idro-Bagolino-Madonna di Campiglio le destinazioni). TORMINI Da Trento ferma a Tione e a Baitoni-Lago d’Idro-Ponte Caffaro, cambiare per Idro MILANO (Vestone - Brescia le destinazioni). BRESCIA Lago di Garda In Aereo Aeroporti di Villafranca 95 km(Verona), Montichiari 55 km (Brescia), Orio al Serio DESENZANO VENEZIA VERONA 105 km (Bergamo) MODENA By car Mit dem Auto From Austria: Motorway: Innsbruck - Brennero (Ita) - Bolzano - Trento (exit the motorway at Von Österreich: Autobahn: Innsbruck – Brenner (Italien) – Bozen – Trient (Autobahnausfahrt Trento Nord) - Tione (head in the direction of Riva until Le Sarche) - Lago d’Idro (in the direction Trento Nord) – Tione (Richtung Riva bis Le Sarche) – Lago d’Idro (Richtung Brescia) – Anfo – Idro. -

Prontuario Per La Pesca Dilettantistica Ricreativa Nel Bacino N. 14 Sebino

PRONTUARIO PER LA PESCA DILETTANTISTICA RICREATIVA NEL BACINO N. 14 SEBINO ANNO 2021 Per informazioni: Struttura Agricoltura, Foreste, Caccia e Pesca Bergamo Via XX Settembre, 18/A - 24122 Bergamo [email protected] [email protected] 035/273.373 - 371 Orari di apertura al pubblico sportello Caccia e Pesca: • dal lunedì al venerdì dalle 9.00 alle 12.30 • mercoledì anche il pomeriggio dalle 14.30 alle 16.30 Struttura Agricoltura, Foreste, Caccia e Pesca Brescia Via Dalmazia, 94 – 25125 Brescia [email protected] [email protected] 030/3462345 – 318 -366 Orari di apertura al pubblico sportello Caccia e Pesca: • da lunedì a giovedì: 9.00-12.30 / 14.30-16.30 • venerdì: dalle 9,00 alle 12,30 INDICE IL BACINO DI PESCA Confini e acque del bacino pag. 3 Classificazione delle acque pag. 3 COSA SERVE PER PESCARE NEL BACINO 14 La licenza di pesca pag. 4 Il tesserino segnapesci pag. 4 NORME PER L’ESERCIZIO DELLA PESCA DILETTANTISTICA RICREATIVA Tempi di pesca pag. 5 Orari di pesca pag. 5 Pesca notturna pag. 5 Periodi di divieto di pesca e misure minime di cattura pag. 5 Fauna ittica protetta pag. 9 Limiti di cattura giornalieri per pescatore pag. 9 Pesca da natante pag. 10 Posto di pesca pag. 10 Attrezzi consentiti pag. 10 Esche e pasture, pesca con il pesce vivo pag. 13 Divieti pag. 13 ZONE A REGOLAMENTAZIONE SPECIALE Zone di protezione e ripopolamento pag. 15 Lago di Iseo - Zone di Tutela con divieto assoluto di pesca professionale e limitazione alla pesca dilettantistica pag. -

Cartella Stampa

Cartella stampa Galleria fotografica: www.fotocru.it/oliogarda/ Il territorio La zona di produzione delle olive del Garda è caratterizzata dalla presenza delle catene montuose a nord e del più grande lago italiano, che rendono il clima gardesano simile a quello mediterraneo e mitigano gli effetti dell’ambiente che, alla latitudine della zona del Garda, sarebbero altrimenti ostili allo sviluppo degli olivi. Le piogge, ben distribuite durante tutto l’anno, salvaguardano gli olivi da stress idrici ed evitano il formarsi di ristagni che sarebbero dannosi sia alla pianta, sia alla qualità dell’olio. Le zone di produzione I produttori dell'oro del lago di Garda sono suddivisi in 67 comuni, per un totale di una ottantina di etichette. Le cultivar più diffuse in questo microclima mediterraneo sono Casaliva, Frantoio e Leccino. Secondo il disciplinare di produzione queste sono le percentuali di cultivar che devono essere presenti per la denominazione DOP nelle tre sottozone: Garda Bresciano DOP Casaliva, Frantoio, Leccino ≥ 55% Garda Orientale DOP Casaliva, Frantoio, Leccino ≥ 55% Garda Trentino DOP Casaliva, Frantoio, Leccino, Pendolino ≥ 80% La Casaliva La cultivar principale e autoctona del territorio del Garda è la Casaliva. Si racconta che venne prescelta dagli olivicoltori della zona per l’ottima resa, la grande qualità e perché genera un olio delicato, fine, ideale per diversi abbinamenti. La Casaliva porta anche il nome di Drizzar, perché si dice che fosse in grado di raddrizzare le sorti del raccolto, maturando anche in maniera scalare e tardiva. Uno dei fattori che l'ha resa protagonista di questo territorio infatti è la sua capacità di adattarsi al clima e al terreno, di sopravvivere ad una gelata e di resistere ai parassiti. -

PROVINCIA COMUNE Adda Lago Di Como LC

IDROSFERA SEL -STATO ECOLOGICO DEI LAGHI (2009) ACQUE LACUSTRI BACINO STAZIONE DI MONITORAGGIO LAGO SEL IDROGRAFICO PROVINCIA COMUNE Adda Lago di Como LC Abbadia Lariana 3 Adda Lago di Como CO Argegno 3 Adda Lago di Piano CO Carlazzo 4 Adda Lago di Annone Est LC Civate 5 Adda Lago di Annone Ovest LC Civate 4 Adda Lago di Como CO Como 3 Adda Lago di Como LC Dervio 3 Adda Lago di Como LC Lecco 3 Adda Lago di Garlate LC Lecco 3 Adda Lago di Sartirana LC Merate 4 Adda Lago di Mezzola SO Verceia 3 Adda Lago del Gallo SO Livigno 2 Adda Lago Palù SO Chiesa in Valmalenco 2 Adda Lago Palabione SO Aprica 2 Adda Lago di Montespluga SO Madesimo 3 Lambro Lago del Segrino CO Eupilio 3 Lambro Lago di Alserio CO Monguzzo 4 Lambro Lago di Montorfano CO Montorfano 4 Lambro Lago di Pusiano CO Pusiano 4 ARPA LOMBARDIA Pagina 1 di 3 IDROSFERA SEL -STATO ECOLOGICO DEI LAGHI (2009) ACQUE LACUSTRI BACINO STAZIONE DI MONITORAGGIO LAGO SEL IDROGRAFICO PROVINCIA COMUNE Mincio Lago di Garda BS Gargnano 2 Mincio Lago di Mezzo MN Mantova 4 Mincio Lago Inferiore MN Mantova 4 Mincio Lago Superiore MN Mantova 4 Mincio Lago di Castellaro MN Monzambano 5 Mincio Lago di Garda BS Padenghe sul Garda 2 Mincio Lago di Garda BS Salo' 3 Mincio Lago di Valvestino BS Valvestino 2 Oglio Lago di Idro BS Anfo 4 Oglio Lago d'Iseo BG Castro 4 Oglio Lago di Iseo BG Predore 3 Oglio Lago di Endine BG Endine Gaiano 4 Oglio Lago di Iseo BS Monte Isola 3 Ticino Lago di Varese VA Biandronno 4 Ticino Lago Maggiore VA Angera 3 Ticino Lago di Lugano VA Lavena Ponte Tresa 4 Ticino Lago di Lugano VA Porto Ceresio 4 Ticino Lago di Monate VA Osmate 3 Ticino Lago di Ghirla VA Valganna 4 ARPA LOMBARDIA Pagina 2 di 3 IDROSFERA SEL -STATO ECOLOGICO DEI LAGHI (2009) ACQUE LACUSTRI BACINO STAZIONE DI MONITORAGGIO LAGO SEL IDROGRAFICO PROVINCIA COMUNE Ticino Lago di Ganna VA Valganna 2 Ticino Lago di Comabbio VA Varano Borghi 4 ARPA LOMBARDIA Pagina 3 di 3. -

The Italian Lakes, the Piedmont, Tuscany, Umbria & Rome

Gardens of Italy: The Italian Lakes, the Piedmont, Tuscany, Umbria & Rome 29 APR – 21 MAY 2019 Code: 21912 Tour Leaders Deryn Thorpe, David Henderson Physical Ratings Enjoy the famous gardens of northern and central Italy, including private masterpieces by Paolo Pejrone, Russell Page, Paolo Portoghesi and Pearson & Barfoot. Overview Tour Highlights Join Deryn Thorpe, award-winning print and radio garden journalist, to tour the gardens of five distinct regions of Italy. Deryn will be accompanied by award-winning artist David Henderson, who brings a profound knowledge of European art to ASA tours. Enjoy the magic of northern lakeside and island gardens including Villa Carlotta, Villa Balbianello, Isola Bella and Isola Madre. Meet Paolo Pejrone, student of Russell Page and currently Italy's leading garden designer. With him, view his own garden, 'Bramafam' and, by special appointment, the private Gardens of Casa Agnelli at Villar Perosa – one of Italy's most splendid examples of garden design. View Paolo Pejrone's work during private visits to the estate of the Peyrani family and the beautiful Tenuta Banna. See the work of Russell Page with an exclusive visit to the private gardens of Villa Silvio Pellico. Visit intimate urban gardens in Florence and Fiesole including Le Balze, designed by Cecil Pinsent; Villa di Maiano (featured in James Ivory's film A Room with a View); and the Giardini Corsini al Prato. Ramble through the historical centres of lovely old cities like Turin, Lucca, Siena, Florence and Perugia, and encounter masterpieces of Italian art in major churches and museums. Gaze out onto the Mediterranean from the spectacularly situated Abbey of La Cervara. -

Presentazione Di Powerpoint

Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale Italian Centre for River Restoration Viale Garibaldi 44/a 30173 – MESTRE (VENICE, ITALY) Tel +39-041-615410 River Restoration: basic concepts Andrea Nardini – Research & Coop. Website: www.cirf.org Email: [email protected]; [email protected] RESTORATION: Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale objective and means more safety allow anthropic activities satisfy recreation, aesthetics & identity RR improve rivers (existence value) reduce costs (investm.&management) enhance landscape and increase urban asset value OBJECTIVE Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale river “HEALTH” Hydraulic RISK Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale RISK: classic hydraulic approach and its effects Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale RISK: classic hydraulic approach and its effects Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale “solid transport”… DAMS RISK: classic hydraulic approach and its effects Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale Increase efficiency, confine flow: levees, canalization + protects against events with: T T* (200) - BUT..... less space to river: accelerated flow, increased peak, lower energy dissipation RISK: classic hydraulic approach and its effects Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale Po river (Italy) Ferrara Northern Italy Po river (Italy): result Centro Italiano per la Riqualificazione Fluviale today… 1954 1705 The “safe conditions” paradox Town Town before after EVENT B EVENT A EVENT A * = * = P D R P D R the risk