BTNG | RBHC, XXXIII, 2003, 3-4, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petroleum in the Spanish Iberian Peninsula

J. E. Ortiz, 0. Puche, I. Rabano and L. F. Mazadiego (eds.) History of Research in Mineral Resources. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, 13. Institute Geologico y Minero de Espana, Madrid. ISBN 978-84-7840-856-6 © Institute Geologico y Minero de Espana 2011 PETROLEUM IN THE SPANISH IBERIAN PENINSULA Octavio Puche Riart, Luis F. Mazadiego Martinez and Jose E. Ortiz Menendez E.T.S. de Ingenieros de Minas, Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, Rios Rosas 21, 28003 Madrid, Spain. [email protected] Abstract. The main events of the history of petroleum in Spain are the following: 1) The mining concession of petroleum named El Progreso is the first one in Spain and occurred only seven years after Edwin Drake (1819-1880) drilled the first oil well in Pennsylvania. 2) The first survey of oil production in Spain, well known as the Tejon borehole, was conducted by the Sondeos de Huidobro Company in 1900, in Huidobro (Burgos), and reached 501 m of depth. 3) In 1964 CAMPSA and AMOSPAIN found petroleum in the Ayoluengo field (Burgos), with a borehole of 1,349 m of depth. This was the first and only petroleum field in the continental Spain in this zone. The Ayoluengo petroleum field has been active during 35 years. In this paper we will review the history of petroleum in peninsular Spain. 1. INTRODUCTION It has been historically known the existence of several oil evidences of solid, liquid and gaseous seeps in Spain. These evidences have guided the identification of areas that are favorable for the research of petroleum deposits. -

AAPG EXPLORER (ISSN 0195-2986) Is Published Monthly for Members by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 1444 S

EXPLORER 2 FEBRUARY 2016 WWW.AAPG.ORG Vol. 37, No. 2 February 2016 EXPLORER PRESIDENT’SCOLUMN What is AAPG ? By BOB SHOUP, AAPG House of Delegates Chair s I have met with increase opportunities for delegates and AAPG our members to network Aleaders around the with their professional peers. world, there has been Ideally, we can address these considerable discussion two priorities together. about what AAPG is, or Our annual meeting should be. There are many (ACE) and our international who believe that AAPG meetings (ICE) provide high- is, and should remain, an quality scientific content association that stands for and professional networking professionalism and ethics. opportunities. However, This harkens back to we can host more regional one of the key purposes Geosciences Technology of founding AAPG in the Workshops (GTWs) and first place. One hundred Hedberg conferences. These years ago, there were types of smaller conferences many charlatans promoting can also provide excellent drilling opportunities based on anything opportunities it offers asked how they view AAPG, the answer scientific content and professional but science. AAPG was founded, in part, at conferences, field was overwhelmingly that they view networking opportunities. to serve as a community of professional trips and education AAPG as a professional and a scientific Another priority for the Association petroleum geologists, with a key emphasis events. association. leadership should be to leverage Search on professionalism. AAPG faces a When reviewing the comments, and Discovery as a means to bring Many members see AAPG as a number of challenges which are available on AAPG’s website, professionals into AAPG. -

Offering Circular Dated November 4Th, 2003

∆ OFFERING CIRCULAR REPSOL INTERNATIONAL FINANCE B.V. (A private company with limited liability incorporated under the laws of the Netherlands and having its statutory seat in Rotterdam) EURO 5,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme Guaranteed by REPSOL YPF, S.A. (A sociedad anónima organised under the laws of the Kingdom of Spain) On October 5, 2001, Repsol International Finance B.V. and Repsol YPF, S.A. (both as defined below) entered into a euro 5,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme. A further Offering Circular describing the Programme was issued on October 21, 2002. With effect from the date hereof, the Programme has been updated and this Offering Circular supersedes any previous Offering Circular issued in respect of the Programme. Any Notes to be issued after the date hereof under the Programme are issued subject to the provisions set out herein, save that Notes which are to be consolidated and form a single series with Notes issued prior to the date hereof will be issued subject to the Conditions of the Notes applicable on the date of Issue for the first tranche of Notes of such series. Subject as aforesaid, this does not affect any Notes issued prior to the date hereof. Under the Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme described in this Offering Circular (the ‘‘Programme’’), Repsol International Finance B.V. (the ‘‘Issuer’’), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Notes guaranteed by Repsol YPF, S.A. (the ‘‘Guarantor’’) (the ‘‘Notes’’). -

A Guide to Sources of Information on Foreign Investment in Spain 1780-1914 Teresa Tortella

A Guide to Sources of Information on Foreign Investment in Spain 1780-1914 Teresa Tortella A Guide to Sources of Information on Foreign Investment in Spain 1780-1914 Published for the Section of Business and Labour Archives of the International Council on Archives by the International Institute of Social History Amsterdam 2000 ISBN 90.6861.206.9 © Copyright 2000, Teresa Tortella and Stichting Beheer IISG All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar worden gemaakt door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Stichting Beheer IISG Cruquiusweg 31 1019 AT Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction – iii Acknowledgements – xxv Use of the Guide – xxvii List of Abbreviations – xxix Guide – 1 General Bibliography – 249 Index Conventions – 254 Name Index – 255 Place Index – 292 Subject Index – 301 Index of Archives – 306 Introduction The purpose of this Guide is to provide a better knowledge of archival collections containing records of foreign investment in Spain during the 19th century. Foreign in- vestment is an important area for the study of Spanish economic history and has always attracted a large number of historians from Spain and elsewhere. Many books have already been published, on legal, fiscal and political aspects of foreign investment. The subject has always been a topic for discussion, often passionate, mainly because of its political im- plications. -

Full Annual Report

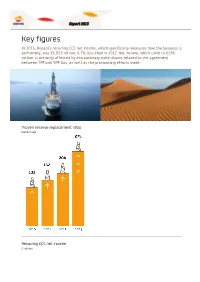

Report 2013 Key figures In 2013, Repsol's recurring CCS net income, which specifically measures how the business is performing, was €1,823 million, 6.7% less than in 2012. Net income, which came to €195 million, is primarily affected by extraordinary write-downs related to the agreement between YPF and YPF Gas, as well as the provisioning efforts made. Proven reserve replacement ratio Percentage Recurring CCS net income € million 2012 2013 1,954 1,823 Net debt * € million * Excluding Gas Natural Fenosa and including preference shares Attracting talent New permanent contracts in 2013 Contribution to society € million Occupational safety Injury frequency rate 0.91 0.59 2012 2013 © Repsol 2000-2014 | www.repsol.com | Legal notice | Accessibility | Contact | Request this report Report 2013 Letter from the Chairman Dear Shareholders, I am pleased to inform you of the most notable events affecting Repsol in 2013 and the first few weeks of 2014. It was precisely during these past few weeks that we finally saw the results of almost two years of intense efforts to achieve suitable compensation for the expropriation from Repsol of 51% of the share capital of YPF and YPF Gas, which took place in April 2012. During these past two years, Repsol's strategy was based on defending the rights and interests of all its shareholders, through a two-pronged approach: a broad and firm legal offensive before the courts and international arbitration bodies, coupled with a willingness to engage in open dialogue toward an amicable compensation agreement that would be satisfactory for the company. "The agreement regarding the expropriation of YPF guarantees suitable financial compensation and allows us to move into a new era free from uncertainty, to shore up our financial strength and to increase our options for growth" This two-pronged strategy finally proved successful. -

Catching Cartels

Catching Cartels An evaluation of using structural breaks to detect cartels in retail markets Author: Sebastian Mårtensson Supervisor: Håkan J. Holm 2nd year Master Thesis in Economics Department of Economics Lund University June 2021 Abstract This thesis evaluates a new method for detecting cartels based on the idea that cartels create structural breaks in their price generating process. The method is evaluated along certain criteria and is further explored using more detailed data on Spanish retail fuel prices. A novel contribution with this thesis is to present an improvement of the method. The method fails to detect cartels and fails to live up to some of the criteria presented. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Håkan J. Holm for his advice and guidance in writing this thesis. It would not have been possible without him and the experience would have not been as interesting. I would also like to thank Meera and Albert for giving valuable feedback and for friends and family for their encouragement. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2. Method evaluation .............................................................................................................. 2 3. Spanish fuel retailers .......................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... -

Base Prospectus Dated October 25Th, 2010

BASE PROSPECTUS REPSOL INTERNATIONAL FINANCE B.V. (A private company with limited liability incorporated under the laws of The Netherlands and having its statutory seat in The Hague) EURO 10,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme Guaranteed by REPSOL YPF, S.A. (A sociedad anónima organised under the laws of the Kingdom of Spain) On 5 October 2001, Repsol International Finance B.V. and Repsol YPF, S.A. entered into a euro 5,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the Programme) and issued an Offering Circular in respect thereof. Further Offering Circulars describing the Programme were issued on 21 October 2002, 4 November 2003, 10 November 2004, 2 February 2007, 28 October 2008 and 23 October 2009. With effect from the date hereof, the Programme has been updated and this Base Prospectus supersedes any previous Offering Circular issued in respect of the Programme. Any Notes (as defined below) to be issued on or after the date hereof under the Programme are issued subject to the provisions set out herein, save that Notes which are to be consolidated and form a single series with Notes issued prior to the date hereof will be issued subject to the Conditions of the Notes applicable on the date of issue for the first tranche of Notes of such series. Subject as aforesaid, this does not affect any Notes issued prior to the date hereof. Under the Programme, Repsol International Finance B.V. (the Issuer), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Notes guaranteed by Repsol YPF, S.A. -

Comercialización Al Por Menor Del Combustible De Automoción En España: Del Monopolio Al Oligopolio

COMERCIALIZACIÓN AL POR MENOR DEL COMBUSTIBLE DE AUTOMOCIÓN EN ESPAÑA: DEL MONOPOLIO AL OLIGOPOLIO BLANCA SÁNCHEZ-FERNÁNDEZ Mª MERCEDES DEL CORO FERNÁNDEZ-FEAL Universidad de A Coruña En los comienzos del siglo XX, en España, ni existía un gran parque automovilístico ni un gran desarrollo industrial que demandasen grandes cantidades de productos petrolíferos. Por ello, los combustibles y carburantes que se comercializaban se importaban de países en los TXH\DH[LVWtDQFHQWURVGHUHÀQRGHOFUXGRGHSHWUyOHR La política arancelaria existente en España ejercía $OÀQDOL]DUODJXHUUDFLYLOHVSDxRODHQ(VSDxDHQ- XQD JUDQ SUHVLyQ ÀVFDO VREUH ORV FUXGRV GH SHWUyOHR WUDHQXQSHULRGRGHJUDQFULVLVHFRQyPLFDSROtWLFD\ este hecho, junto a lo reducido del mercado en esos VRFLDO OD SRVJXHUUD VH DODUJy GHELGR DO DLVODPLHQWR PRPHQWRV GHVDFRQVHMDED OD LQVWDODFLyQ GH XQD LQ- SROtWLFR \ HFRQyPLFR DO TXH VH YLR VRPHWLGD (VSDxD GXVWULD UHÀQHUD TXH H[LJtD XQ FRQVLGHUDEOH YROXPHQ como consecuencia de su régimen político (la dictadu- GH SURGXFFLyQ SDUD VHU UHQWDEOH 3RU HOOR ORV LPSRU- UDGHO*HQHUDO)UDQFR (OQXHYRUpJLPHQFUHyHQ tadores adquirían en el exterior productos intermedios un Patronato, dependiente del Ministerio de Hacienda, SDUD VX SRVWHULRU WUDQVIRUPDFLyQ (Q HO SHUtRGR FRP- SDUDODSURYLVLyQGH$JHQFLDVGH$SDUDWRV6XUWLGRUHVGH prendido entre 1900 y 1927, como consecuencia del Gasolina (Ley 22 de julio de 1939 y sus normas com- FUHFLPLHQWRHFRQyPLFRH[SHULPHQWDGRHQHVRVPR- SOHPHQWDULDV SRUHOTXHVHDGMXGLFDEDHOGHODV PHQWRVMXQWRDODGLIXVLyQGHODXWRPyYLOVHSURGXMRHQ vacantes de agentes de -

Merger Decision IV/M.111 of 29.07.1991

EN Case No IV/M.111 - BP / PETROMED Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 29.07.1991 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 391M0111 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg Brussels 29.07.1991 MERGER PROCEDURE ARTICLE 6(1)b DECISION PUBLIC VERSION Registered with advice of delivery To notifying party Dear Sirs, Subject: Case No. IV/M111 - BP/Petromed Your notification persuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation Mo. 4064/89 1. The above mentioned notification concerns the agreement between BANCO ESPAÑOL DE CREDITO S.A. and CORPORACION INDUSTRIAL Y FINANCIERA DE BANESTO S.A. (the vendors), and BP ESPAÑA S.A., a wholly owned indirect subsidiary of the British Petroleum Company plc ("BP"), by which BP ESPAÑA S.A. will acquire the totality of the shares of PETROLEOS DEL MEDITERRANEO S.A. (PETROMED) owned by the vendors. Additionally, BP ESPAÑA S.A. undertakes to launch a public bid for the remaining shares of PETROMED. The public bid was announced on 30.6.1991. 2. After examination of the notification, the Commission has concluded that the notified operation falls within the scope of Council Regulation No. 4064/89 (Merger Regulation) and does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibily with the common market. Rue de la Loi 200 - B-1049 Brussels - Belgium ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Telephone: direct line 29..... exchange 299.11.11 - Telex COMEU B 21822 - Telegraphic address COMEUR Brussels telefax 29....... - 2 - I. CONCENTRATION 3. -

REPSOL YPF Executive

Toledo, 1988 III CONTENTS FOREWORD............................................................................... V OPENING SESSION WELCOMING REMARKS MR. GUZMÁN SOLANA........................................... 1 «THE FUTURE OF SPAIN´S OIL SECTOR» MR. VÍCTOR PÉREZ PITA......................................... 3 SESSION I: OIL MARKET OUTLOOK INTRODUCTORY REMARKS MR. BIJAN MOSSAVAR - RAHMANI ......................... 7 «WORLD OIL MARKET OUTLOOK FOR THE 1990S» MR. JOHN PIERCE FERRITER .................................... 13 «OIL MARKETS AND OIL PRICES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS» MR. WILLIAM W. HOGAN ...................................... 25 «PROSPECTS FOR THE WORLD OIL INDUSTRY» MR. ALAN NAISMITH BINDER .................................. 53 SESSION II: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN OIL AND MONEY INTRODUCTORY REMARKS MRS. EIJA MALMIVIRTA .......................................... 67 «CRUDE OIL FORWARD AND FUTURE MARKETS: A COMPARISON OF BRENT AND WTI» MR. ROBERT J. WEINER .......................................... 73 «THE ROLE OF FUTURES IN A GLOBAL ENERGY MARKET» MR. ROBERT RYAN................................................. 83 IV «A PRACTITIONER´S VIEW OF THE OIL AND MONEY MARKETS» MR. ERNST WEIL .................................................... 95 SESSION III: ENERGY IN WESTERN EUROPE IN THE RUN-UP TO 1992 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS MR. JOSÉ SIERRA .................................................... 101 «THE WEST EUROPEAN NATURAL GAS MARKET IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF INTEGRATION AND ELECTRICITY DEMAND: NEW CHALLENGES TO ENERGY POLICY» MR. OYSTEIN NORENG -

The Spanish Distribution System of Oil Products: an Economic Analysis

The Spanish distribution system of oil products: an economic analysis Ignacio Contín*, Aad Correljé**, and Emilio Huerta*** This paper is concerned with the structure and regulation of the Spanish distribution system of oil products. Spanish-based refiners have a dominant position on the commercialisation of oil products. The Compañía Logística de Hidrocarburos (CLH), a joint venture between the three Spanish-based refiners and Shell, is the only firm that distributes oil products by pipelines in Spain. It also owns most of the storage capacity ex-refineries. CLH constitutes a “bottleneck” in the recently liberalised Spanish oil market, in particular, for transport inland. As a result, the government decided to regulate CLH in June 1996. However, more transparency should be achieved in this regulation. 1. Introduction The Spanish oil industry was dominated by a state monopoly between 1927 and 1993. The oil sector was vertically disintegrated while the government strictly regulated the commercial relationships between companies involved. Ex-refinery and retail prices were imposed administratively. The government established the size of the deliveries from the refiners to the monopoly. The monopoly was operated by CAMPSA (Compañía Arrendataria del Monopolio de Petróleos Sociedad Anónima) which took care of distribution and marketing, either by its own service stations or by concessionaires. Following a rigorous reorganisation from the early 1980s onwards, Spain began to gradually liberalise its oil industry in order to adapt it to European competition rules and to address the instabilities inherent in the prevailing system of regulation. Access to various segments of the oil chain (distribution, transport, storage, and retail trade) was gradually opened up to new domestic and foreign operators. -

Dígitos Manuales EE.SS. DIGIT·M Para Marcadores De Precios De EE

MODULARSIGNS Dígitos Manuales EE.SS. DIGIT·M para marcadores de precios de EE. SS. Dígitos manuales para EE. SS. DIGIT·M es un producto desarrollado especí- fi camente para marcadores de precios en es- taciones de servicio. Digit·M es una evolución de los existentes en el mercado, en acabado, duración del mate- rial y servicio al cliente, con una amplia gama de colores homologados en stock y la posibi- lidad de suministrar otros colores. En la fabri- cación de los dígitos, se ha estudiado la resis- tencia de los materiales para obtener mayor rendimiento, garantizando una larga duración y continuidad en colores y acabados. PAT.U9901830 2 señalización | DIGIT·M 1 PINZA TAPA 2 Dígit M 3 4 elementos de un dígito Dígitos manuales Proceso de montaje Dígitos 1. Corte del vinilo con plóter. 2. Pelado del vinilo. GDC60 c a 3. Taladro y montaje de pinzas. c 2 (Negro), 3 (Gris Repsol RAL 7016), 4 (Gris Repsol RAL 7011), 4. Inserción de los fl aps. 5 (Rojo Cepsa RAL 3020), 6 (Azul Repsol RAL 5004), 7 (Azul Campsa RAL 5002), 8 (Verde BP RAL 6029) a 15 (Altura 153 mm), 23 (Altura 230 mm), 30 (Altura 300 mm) Dígito formado por 7 tapas abatibles y 14 pinzas con muelle para sujec- www.modular-signs.net, sección descargas. ción posterior inyectado en negro y colores. Dibujos a E 1:1, con la posición de los tala- wwwdros. Tapas numeradas según su posición. Pinzas para dígitos COMPOSICIÓN DEL FLAP: GDC60 c 51 ASA c 2 (Negro), 3 (Gris Repsol RAL 7016), 4 (Gris Repsol RAL 7011), COMPOSICIÓN DE LA PINZA: 5 (Rojo Cepsa RAL 3020), 6 (Azul Repsol RAL 5004), 7 (Azul Campsa POM RAL 5002), 8 (Verde BP RAL 6029) Fabricado bajo control ISO 9001 con materiales de alta Pinzas con muelle para dígitos.