Petroleum in the Spanish Iberian Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A High-Resolution Daily Gridded Precipitation Dataset for Spain – an Extreme Events Frequency and Intensity Overview

Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 9, 721–738, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-721-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. SPREAD: a high-resolution daily gridded precipitation dataset for Spain – an extreme events frequency and intensity overview Roberto Serrano-Notivoli1,2,3, Santiago Beguería3, Miguel Ángel Saz1,2, Luis Alberto Longares1,2, and Martín de Luis1,2 1Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, 50009, Spain 2Environmental Sciences Institute (IUCA), University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, 50009, Spain 3Estación Experimental de Aula Dei, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (EEAD-CSIC), Zaragoza, 50059, Spain Correspondence to: Roberto Serrano-Notivoli ([email protected]) Received: 5 May 2017 – Discussion started: 7 June 2017 Revised: 17 August 2017 – Accepted: 18 August 2017 – Published: 14 September 2017 Abstract. A high-resolution daily gridded precipitation dataset was built from raw data of 12 858 observato- ries covering a period from 1950 to 2012 in peninsular Spain and 1971 to 2012 in Balearic and Canary islands. The original data were quality-controlled and gaps were filled on each day and location independently. Using the serially complete dataset, a grid with a 5 × 5 km spatial resolution was constructed by estimating daily pre- cipitation amounts and their corresponding uncertainty at each grid node. Daily precipitation estimations were compared to original observations to assess the quality of the gridded dataset. Four daily precipitation indices were computed to characterise the spatial distribution of daily precipitation and nine extreme precipitation in- dices were used to describe the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events. -

AAPG EXPLORER (ISSN 0195-2986) Is Published Monthly for Members by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 1444 S

EXPLORER 2 FEBRUARY 2016 WWW.AAPG.ORG Vol. 37, No. 2 February 2016 EXPLORER PRESIDENT’SCOLUMN What is AAPG ? By BOB SHOUP, AAPG House of Delegates Chair s I have met with increase opportunities for delegates and AAPG our members to network Aleaders around the with their professional peers. world, there has been Ideally, we can address these considerable discussion two priorities together. about what AAPG is, or Our annual meeting should be. There are many (ACE) and our international who believe that AAPG meetings (ICE) provide high- is, and should remain, an quality scientific content association that stands for and professional networking professionalism and ethics. opportunities. However, This harkens back to we can host more regional one of the key purposes Geosciences Technology of founding AAPG in the Workshops (GTWs) and first place. One hundred Hedberg conferences. These years ago, there were types of smaller conferences many charlatans promoting can also provide excellent drilling opportunities based on anything opportunities it offers asked how they view AAPG, the answer scientific content and professional but science. AAPG was founded, in part, at conferences, field was overwhelmingly that they view networking opportunities. to serve as a community of professional trips and education AAPG as a professional and a scientific Another priority for the Association petroleum geologists, with a key emphasis events. association. leadership should be to leverage Search on professionalism. AAPG faces a When reviewing the comments, and Discovery as a means to bring Many members see AAPG as a number of challenges which are available on AAPG’s website, professionals into AAPG. -

A Report on the Potential of Renewable Energies in Peninsular Spain

A report on the potential of renewable energies in peninsular Spain © Raúl Bartolomé Greenpeace Madrid San Bernardo, 107, 28015 Madrid Tel.: 91 444 14 00 - Fax: 91 447 15 98 [email protected] Greenpeace Barcelona Ortigosa, 5 - 2º 1ª, 08003 Barcelona Tel.: 93 310 13 00 - Fax: 93 310 51 18 Authors: José Luis García Ortega and Alicia Cantero Layout and design: De••Dos, espacio de ideas Greenpeace is a politically and economically independent organisation. Join by calling 902 100 505 or at www.greenpeace.es This report has been printed on paper recycled after use and bleached without chlorine, with Blue Angel certification, in order to preserve forests, save energy and prevent the pollution of seas and rivers. November 2005 Contents 1. Introduction 04 2. Hypothesis and methodology 06 3. The main results of the study 08 3.1. Results by technologies 08 1. Geothermal 09 2. Hydro-electric 10 3. Biomass 11 4. Waves 12 5. Off shore wind 13 6. On-shore wind 14 7. Solar chimney 15 8. Solar photovoltaic integrated into buildings 16 9. Solar photovoltaic with tracking 17 10. Concentrated solar thermal 18 3.2. Summary of results 19 Fully available renewable resources 19 Comparison with the Renewable Energy Plan 20 Meeting electricity demand: proposed generation mix 21 Meeting total energy demand: proposed mix 22 3.3. Results by Autonomous Community 24 Andalusia 24 Aragon and Asturias 25 Cantabria and Castile-La Mancha 26 Castile-Leon and Catalonia 27 Extremadura and Galicia 28 Madrid and Murcia 29 Navarre and the Basque Country 30 La Rioja and Valencia 31 4. -

Spain Groundwater Country Report.Pdf

Groundwater in the Southern Member States of the European Union: an assessment of current knowledge and future prospects Country report for Spain Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Scope ....................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Groundwater Resources .......................................................................................................... 3 4. Groundwater Use in Spain ...................................................................................................... 6 5. The Economic Aspects of Groundwater Use in Spain............................................................ 8 6. Pressures, Impacts and Measures to Achieve the Goals of the Water Framework Directive ........................................................................................ 19 7. Institutions for Groundwater Governance ............................................................................ 25 8. Conclusions ........................................................................................................................... 33 References ................................................................................................................................. 33 Relevant Websites ..................................................................................................................... 38 GROUNDWATER -

Offering Circular Dated November 4Th, 2003

∆ OFFERING CIRCULAR REPSOL INTERNATIONAL FINANCE B.V. (A private company with limited liability incorporated under the laws of the Netherlands and having its statutory seat in Rotterdam) EURO 5,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme Guaranteed by REPSOL YPF, S.A. (A sociedad anónima organised under the laws of the Kingdom of Spain) On October 5, 2001, Repsol International Finance B.V. and Repsol YPF, S.A. (both as defined below) entered into a euro 5,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme. A further Offering Circular describing the Programme was issued on October 21, 2002. With effect from the date hereof, the Programme has been updated and this Offering Circular supersedes any previous Offering Circular issued in respect of the Programme. Any Notes to be issued after the date hereof under the Programme are issued subject to the provisions set out herein, save that Notes which are to be consolidated and form a single series with Notes issued prior to the date hereof will be issued subject to the Conditions of the Notes applicable on the date of Issue for the first tranche of Notes of such series. Subject as aforesaid, this does not affect any Notes issued prior to the date hereof. Under the Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme described in this Offering Circular (the ‘‘Programme’’), Repsol International Finance B.V. (the ‘‘Issuer’’), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Notes guaranteed by Repsol YPF, S.A. (the ‘‘Guarantor’’) (the ‘‘Notes’’). -

The Landforms of Spain

UNIT The landforms k 1 o bo ote Work in your n of Spain Spain’s main geographical features Track 1 Spain’s territory consists of a large part of the Iberian Peninsula, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea and the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, located on the north coast of Africa. All of Spain’s territory is located in the Northern Hemisphere. Peninsular Spain shares a border with France and Andorra to the north and with Portugal, which is also on the Iberian Peninsula, to the west. The Cantabrian Sea and the Atlantic Ocean border the north and west coast of the Peninsula and the Mediterranean Sea borders the south and east coast. The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea. The Canary Islands, however, are an archipelago located almost 1 000 kilometres southwest of the Peninsula, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, just north of the coast of Africa. Spain is a country with varied terrain and a high average altitude. Spain’s high average altitude is due to the numerous mountain ranges and systems located throughout the country and the fact that a high inner plateau occupies a large part of the Peninsula. The islands are also mostly mountainous and have got significant elevations, especially in the Canary Islands. Northernmost point 60°W 50°W 40°W 30°W 20°W 10°W 0° 10°E 20°E 30°E 40°E 50°E 60°N Southernmost point Easternmost point s and Westernmost point itie y iv ou ct ! a m 50°N r Estaca o S’Esperó point (Menorca), f de Bares, 4° 19’ E d ATLANTIC 43° 47’ N n a L 40°N ltar Gibra Str. -

A Guide to Sources of Information on Foreign Investment in Spain 1780-1914 Teresa Tortella

A Guide to Sources of Information on Foreign Investment in Spain 1780-1914 Teresa Tortella A Guide to Sources of Information on Foreign Investment in Spain 1780-1914 Published for the Section of Business and Labour Archives of the International Council on Archives by the International Institute of Social History Amsterdam 2000 ISBN 90.6861.206.9 © Copyright 2000, Teresa Tortella and Stichting Beheer IISG All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar worden gemaakt door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Stichting Beheer IISG Cruquiusweg 31 1019 AT Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction – iii Acknowledgements – xxv Use of the Guide – xxvii List of Abbreviations – xxix Guide – 1 General Bibliography – 249 Index Conventions – 254 Name Index – 255 Place Index – 292 Subject Index – 301 Index of Archives – 306 Introduction The purpose of this Guide is to provide a better knowledge of archival collections containing records of foreign investment in Spain during the 19th century. Foreign in- vestment is an important area for the study of Spanish economic history and has always attracted a large number of historians from Spain and elsewhere. Many books have already been published, on legal, fiscal and political aspects of foreign investment. The subject has always been a topic for discussion, often passionate, mainly because of its political im- plications. -

Full Annual Report

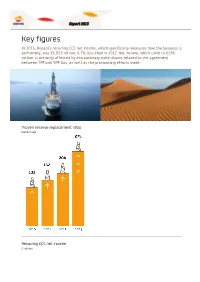

Report 2013 Key figures In 2013, Repsol's recurring CCS net income, which specifically measures how the business is performing, was €1,823 million, 6.7% less than in 2012. Net income, which came to €195 million, is primarily affected by extraordinary write-downs related to the agreement between YPF and YPF Gas, as well as the provisioning efforts made. Proven reserve replacement ratio Percentage Recurring CCS net income € million 2012 2013 1,954 1,823 Net debt * € million * Excluding Gas Natural Fenosa and including preference shares Attracting talent New permanent contracts in 2013 Contribution to society € million Occupational safety Injury frequency rate 0.91 0.59 2012 2013 © Repsol 2000-2014 | www.repsol.com | Legal notice | Accessibility | Contact | Request this report Report 2013 Letter from the Chairman Dear Shareholders, I am pleased to inform you of the most notable events affecting Repsol in 2013 and the first few weeks of 2014. It was precisely during these past few weeks that we finally saw the results of almost two years of intense efforts to achieve suitable compensation for the expropriation from Repsol of 51% of the share capital of YPF and YPF Gas, which took place in April 2012. During these past two years, Repsol's strategy was based on defending the rights and interests of all its shareholders, through a two-pronged approach: a broad and firm legal offensive before the courts and international arbitration bodies, coupled with a willingness to engage in open dialogue toward an amicable compensation agreement that would be satisfactory for the company. "The agreement regarding the expropriation of YPF guarantees suitable financial compensation and allows us to move into a new era free from uncertainty, to shore up our financial strength and to increase our options for growth" This two-pronged strategy finally proved successful. -

Catching Cartels

Catching Cartels An evaluation of using structural breaks to detect cartels in retail markets Author: Sebastian Mårtensson Supervisor: Håkan J. Holm 2nd year Master Thesis in Economics Department of Economics Lund University June 2021 Abstract This thesis evaluates a new method for detecting cartels based on the idea that cartels create structural breaks in their price generating process. The method is evaluated along certain criteria and is further explored using more detailed data on Spanish retail fuel prices. A novel contribution with this thesis is to present an improvement of the method. The method fails to detect cartels and fails to live up to some of the criteria presented. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Håkan J. Holm for his advice and guidance in writing this thesis. It would not have been possible without him and the experience would have not been as interesting. I would also like to thank Meera and Albert for giving valuable feedback and for friends and family for their encouragement. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2. Method evaluation .............................................................................................................. 2 3. Spanish fuel retailers .......................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... -

Base Prospectus Dated October 25Th, 2010

BASE PROSPECTUS REPSOL INTERNATIONAL FINANCE B.V. (A private company with limited liability incorporated under the laws of The Netherlands and having its statutory seat in The Hague) EURO 10,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme Guaranteed by REPSOL YPF, S.A. (A sociedad anónima organised under the laws of the Kingdom of Spain) On 5 October 2001, Repsol International Finance B.V. and Repsol YPF, S.A. entered into a euro 5,000,000,000 Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the Programme) and issued an Offering Circular in respect thereof. Further Offering Circulars describing the Programme were issued on 21 October 2002, 4 November 2003, 10 November 2004, 2 February 2007, 28 October 2008 and 23 October 2009. With effect from the date hereof, the Programme has been updated and this Base Prospectus supersedes any previous Offering Circular issued in respect of the Programme. Any Notes (as defined below) to be issued on or after the date hereof under the Programme are issued subject to the provisions set out herein, save that Notes which are to be consolidated and form a single series with Notes issued prior to the date hereof will be issued subject to the Conditions of the Notes applicable on the date of issue for the first tranche of Notes of such series. Subject as aforesaid, this does not affect any Notes issued prior to the date hereof. Under the Programme, Repsol International Finance B.V. (the Issuer), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue Guaranteed Euro Medium Term Notes guaranteed by Repsol YPF, S.A. -

39 • Spanish Peninsular Cartography, 1500–1700 David Buisseret

39 • Spanish Peninsular Cartography, 1500–1700 David Buisseret Introduction well aware of the value of maps, and, like his successor, Philip II, was seriously concerned with encouraging the Spanish peninsular and European cartography under the production of a good map of the peninsula. Both Habsburgs has largely been overshadowed in the literature Charles V and Philip II were surrounded by nobles and by accounts of the remarkable achievements of Spanish advisers who used and collected maps, as were their suc- mapmakers in the New World. Yet Spain’s cartographers, cessors Philip III, Philip IV, and Charles II. both of the Old World and of the New, came out of the If none of them succeeded in their various efforts to pro- same institutions, relied on the same long-established tra- duce a new and accurate printed map of the whole penin- ditions, called on the same rich scientific milieu, and in sula, it was partly due to the general decline that set in dur- many cases developed similar solutions to their respective ing the second part of the reign of Philip II. For a variety cartographic problems.1 of reasons, the economy fell into disarray, and the society In the late Middle Ages, many influences were at work became less and less open to outside influences. This had in the territories of the Catholic Monarchs (of Castile and a particularly harmful effect on intellectual life; the print- Aragon), with many different cartographic traditions. To ing industry, for instance, was crippled both by the eco- the west, the Portuguese were pushing the portolan chart nomic downturn and by rigid regulation of the press. -

Spain Country Handbook 1

Spain Country Handbook 1. This handbook provides basic reference information on Spain, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and transportation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military personnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to Spain. 2. This product is published under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Production Program (DoDIPP) with the Marine Corps Intelligence Activity designated as the community coordinator for the Country Handbook Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on Spain. 3. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, NATO member countries, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. 4. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for training. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this document, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. CONTENTS KEY FACTS. 1 U.S. MISSION . 2 U.S. Embassy. 2 U.S. Consulate . 2 Travel Advisories. 2 Entry Requirements . 3 Customs Restrictions . 3 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE . 5 Geography . 5 Bodies of Water. 6 Drainage . 6 Topography . 6 Climate. 7 Vegetation . 10 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION . 11 Transportation . 11 Roads . 11 Rail . 14 Maritime . 16 Communication . 17 Radio and Television. 17 Telephone and Telegraph . 18 Newspapers and Magazines .