Community-Based Newborn Care in Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment and Prioritization of Major Camel Diseases in Selected Areas of Afar Regional State, Samara, Ethiopia

Middle East Journal of Applied Science & Technology (MEJAST) (Peer Reviewed International Journal) Volume 3, Issue 1, Pages 23-32, January-March 2020 Assessment and Prioritization of Major Camel Diseases in Selected Areas of Afar Regional State, Samara, Ethiopia Wossene Negash1*, Nuru Seid1 & Fikru Gizaw1 1College of Veterinary Medicine, Samara University, P.O. Box, 132, Samara, Ethiopia. 1*Email: [email protected] Article Received: 11 December 2019 Article Accepted: 07 February 2020 Article Published: 17 March 2020 ABSTRACT A cross sectional study was carried out from January to July 2014 GC in an attempt to assess and prioritize major camel diseases and identify risk factors in the selected areas of Afar region. Camel owners’ interview and retrospective data analysis were the study methods employed. Relevant collected data were organized, filtered and fed into Microsoft Excel sheet and further analyzed using SPSS statistical tools at P< 0.05. Descriptive statistics was carried to determine frequencies of camel diseases camel. Based on descriptive statistics, the study identified and prioritized 16 camel diseases. Chi-Square analysis was computed to measure the degree of association between disease occurrence and risk factors (age, sex, study area and season). Binomial and multinomial logistic regression analyzes were computed at P<0.05 to measure the significance of associated risk factors on disease occurrence. Statistically significant variations (P<0.05) were observed for sex, seasons, age, and study sites on the occurrence of disease with exception kebeles (P>0.05). Though the study duly has revealed numerous diseases of the camel, the actual existence (laboratory based confirmation) and epidemiology of each disease still demands further investigative studies. -

Role of Agricultural Education in the Development of Agriculture in Ethiopia Dean Alexander Elliott Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1957 Role of agricultural education in the development of agriculture in Ethiopia Dean Alexander Elliott Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons, and the Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Elliott, Dean Alexander, "Role of agricultural education in the development of agriculture in Ethiopia " (1957). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1348. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1348 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROLE OP AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE IN ETHIOPIA by Dean Alexander Elliott A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Vocational Education Approved Signature was redacted for privacy. Charge of Major Work Signature was redacted for privacy. Hea Ma^ctr^partrnent Signature was redacted for privacy. Dé ah of Graduate Iowa State College 1957 il TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 COUNTRY AND PEOPLE .... ..... 5 History 5 Geography 16 People 30 Government 38 Ethiopian Orthodox Church lj.6 Transportation and Communication pif. NATIVE AGRICULTURE 63 Soils 71 Crops 85 Grassland and Pasture 109 Livestock 117 Land Tenure 135? GENERAL AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION 162 Organization and Administration 165 Teacher Supply and Teacher Education 175 Schools and Colleges 181}. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

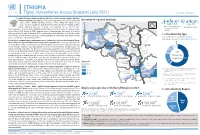

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Report on Evaluation of W SH

Report on Evaluation of WASH - Joint Action Plan (JAP) implementation in eight water insecure Woredas in Afar Regional state Submitted to UNICEF – Ethiopia WASH Section/Afar Field office Prepared by Tesfa Aklilu WASH - Consultant (CIPM, BSc, MPH, MSc (pending, AAU) November 13, 2015 Afar – Semera - Ethiopia | P a g e Table of contents Table of figures .............................................................................................................................................. i Tables ............................................................................................................................................................. i Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... ii WASHCOs: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Committees ........................................................... ii Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................ ii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ iii 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Objectives of Evaluation ............................................................................................................... 2 2.1. General -

Hum Ethio Manitar Opia Rian Re Espons E Fund D

Hum anitarian Response Fund Ethiopia OCHA, 2011 OCHA, 2011 Annual Report 2011 Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Response Fund – Ethiopia Annual Report 2011 Table of Contents Note from the Humanitarian Coordinator ................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 2011 Humanitarian Context ........................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Map - 2011 HRF Supported Projects ............................................................................................. 6 2. Information on Contributors ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Donor Contributions to HRF .......................................................................................................... 7 3. Fund Overview .................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Summary of HRF Allocations in 2011 ............................................................................................ 8 3.1.1 HRF Allocation by Sector ....................................................................................................... -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

The Case of Alamata and Atsbi-Wonberta Woredas of Tigray Region

MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS OF POULTRY: THE CASE OF ALAMATA AND ATSBI-WONBERTA WOREDAS OF TIGRAY REGION M.Sc. Thesis Dawit Gebregziabher January 2010 Haramaya University MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS OF POULTRY: THE CASE OF ALAMATA AND ATSBI-WONBERTA WOREDAS OF TIGRAY REGION A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Agricultural Economics, School of Graduate Studies HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AGRICULTURE (AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS) BY Dawit Gebregziabher January 2010 Haramaya University APPROVAL SHEET SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY As thesis research advisors, we here by certify that we have read and evaluated this thesis prepared, under our guidance, by Dawit Gebregziabher entitled “Market Chain Analysis of Poultry: the case of Alamata and Atsbi Wonberta Woredas of Tigray Region.” We recommend that it be submitted as fulfilling the thesis requirement. Berhanu Gebremedhin (PhD) __________________ ______________ Major Advisor Signature Date Dirk Hoekstra (Mr) __________________ _____________ Co-Advisor Signature Date As member of the Board of Examiners of the M.Sc Thesis Open Defense, we certify that we have read, evaluated the Thesis prepared by Dawit Gebregziabher Mekonen and examine the candidate. We recommend that the Thesis be accepted as fulfilling the Thesis requirement for the Degree of Master of Science in Agriculture (Agricultural Economics). DegnetAbebaw (PhD) __________________ _____________ Chair Person Signature Date Adem Kedir (Mr) __________________ _____________ Internal Examiner Signature Date Admasu Shbiru (PhD) __________________ _____________ External Examiner Signature Date ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis manuscript to my family for their moral and encouragement in the study period in particular and throughout my life in general. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Regreening of the Northern Ethiopian Mountains: Effects on Flooding and on Water Balance

PATRICK VAN DAMME THE ROLE OF TREE DOMESTICATION IN GREEN MARKET PRODUCT VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 129-147 REGREENING OF THE NORTHERN ETHIOPIAN MOUNTAINS: EFFECTS ON FLOODING AND ON WATER BALANCE Tesfaalem G. Asfaha (1,2), Michiel De Meyere (2), Amaury Frankl (2), Mitiku Haile (3), Jan Nyssen (2) (1) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Mekelle University, Ethiopia (2) Department of Geography, Ghent University, Belgium (3) Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, Ethiopia The hydro-geomorphology of mountain catchments is mainly determined by vegetation cover. This study was carried out to analyse the impact of vegetation cover dynamics on flooding and water balance in 11 steep (0.27-0.65 m m-1) catchments of the western Rift Valley escarpment of Northern Ethiopia, an area that experienced severe deforestation and degradation until the first half of the 1980s and considerable reforestation thereafter. Land cover change analysis was carried out using aerial photos (1936,1965 and 1986) and Google Earth imaging (2005 and 2014). Peak discharge heights of 332 events and the median diameter of the 10 coarsest bedload particles (Max10) moved in each event in three rainy seasons (2012-2014) were monitored. The result indicates a strong re- duction in flooding (R2 = 0.85, P<0.01) and bedload sediment supply (R2 = 0.58, P<0.05) with increas- ing vegetation cover. Overall, this study demonstrates that in reforesting steep tropical mountain catchments, magnitude of flooding, water balance and bedload movement is strongly determined by vegetation cover dynamics. -

IOM in Ethiopia IOM PRESENCEIOM Presence in Ethiopia in ETHIOPIA2021

0 IOM in Ethiopia IOM PRESENCEIOM Presence in Ethiopia IN ETHIOPIA2021 Dalol ERITREA TIGRAY Shire Central YEMEN Western Welkait Tselemti Afdera Zone 2 North Gondar Mekele SUDAN Metema Bidu LEGEND Kinfaz Central Gondar Ofla Teru Kurri Country Office Zone 4 Elidar West Gondar Takusa Quara Lake Tana Alfa Zone 1 DJIBOUTI Jawi North Wello Ewa Sub-Offices Chifra Semera Guba AMHARA Dangura Bahir Dar Mile Migration Response Adaa'r Awi Centres (MRCs) Metekel South Wello AFAR Ayisha Wenbera Medical Health Assessment Gablalu East Gojam Gewane Centre (MHAC) Siti BENISHANGUL GUMUZ Zone 3 Shinile Dembel Transit centres Assossa East Togochale Kemashi North Shewa Wellega Horo Guduru North Shewa SOMALIA DIRE DAWA SOUTH SUDAN West Wellega Nekemte 3 Country Capital West Shewa HARARI Jigjiga Fafan Kelem Wellega Harshin ADDIS ABABA East Hararge Regional Capitals South West Hararge West Shewa East Shewa Buno Bedele Daror Itang Ilu Aba Bora Guraghe Fik Disputed Boundaries elit, Gashamo ng ci is p i Jarar d a Gambela r e u t e t c e s Akobo n co t, me t a Arsi i r s Jimma GAMBELA lo Lege Hida Erer o d m u s p i Siltie m e r o Seru Galhamur Agnewak L Burqod Dig International Boundary Cheka Hadiya Sagag Bokh Gog Danod Garbo Kefa OROMIA Seweyna Marsin Doolo Dima Ayun Nogob Regional Boundary Bench Maji Dawuro West Arsi Konta Wolayita Hawassa SOMALI Galadi Rayitu Goglo Warder Bale East Imi SNNPR Sidama Danan Zone Boundary Korahe Gofa Mirab Omo Gamo Gedeo Countries Surma Maji Elkare/Serer Shilabo Male Amaro Meda Welabu Shabelle Bule Hora Guji Water Bodies Hargele Adadle South Omo West Guji Kelafo Konso Liben Charati Afder Ferfer Liban Hamer Filtu Arero Elwaya Yabelo Teltale Barey Dolobay Borena Wachile Mubarek Daawa Dilo Dhas Dolo Ado KENYA Dire Moyale Miyo UGANDA Sources: CSA 2007, ESRI, IOM Date: 3 February 2019 Disclaimer : This map is for illustration purposes only. -

The Effect of Community-Based Interventions on Increasing Family

The Effect of Community-Based Interventions on Increasing Family Planning Utilization in Pastoralist Community of Afar Region Ethiopia: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial By: Mussie Alemayehu Gebreselassie (B.SC, MPH/RH) Advisors: Dr.Afework Mulugeta (Ph.D., Associate Professor) Dr.Araya Abrha (Ph.D., Associate Professor) Feb, 2018 Mekelle, Ethiopia i | P a g e Summary Introduction: Pastoralism, practiced on a quarter of the globe’s surface. An estimated 50 million pastoralists live in sub-Saharan Africa. In Ethiopia, pastoralist community contributes to 12-15% of the total population and 60% of the surface area. Based on the report of Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2016 (EDHS) report, Ethiopia shows an impressive gain in family planning utilization. However, such gain is not uniformly distributed across the agrarian and pastoralist region. The Afar region was one of the regions with low performance of family planning utilization (11.6%). Therefore, this study aims at quantifying the effect of the community-based intervention which includes male involvement and women education on increasing family planning service utilization in pastoralist community from Afar region. Methods: A cluster randomized controlled trial with three arm studies will be employed in 33 clusters of pastoralist community from Afar region. The intervention includes women education and male involvement in family planning utilization and this will be compared with the control group. A total of three data at pre-intervention, midline (follow-up) and post-intervention data will be collected with a four and half months time gap. The data structure will be restructured following collecting the baseline data to enable for follow up of the mother. -

COUNTRY Food Security Update

ETHIOPIA Food Security Outlook Update June 2013 The delayed Belg harvest prolongs lean season in southern and eastern Belg-producing areas Figure 1. Current food security outcomes, June 2013 KEY MESSAGES • Following a three- to four-week delayed onset of the rains which delayed planting and crop development, Belg crops will likely not be harvested until mid-July in southern and eastern Belg-producing areas instead of mid-June. The delayed harvest prevents the timely planting of short-cycle Meher crops on the same land. • The poor performance of February to May Belg rains in the northeastern receiving areas is likely to result in a well below average and delayed Belg harvest, increasing food insecurity from July to September. In parts of the southern areas, food security will improve from Crisis (IPC Phase 3) in some areas to Stressed (IPC Phase 2) with increased supply from the Belg harvest, even if that harvest is both late and somewhat below average. Source: FEWS NET Ethiopia • The good performance of March to May Gu/Genna rains Figure 2. Projected food security outcomes, July to increased milk production, so the food security situation September 2013 in southern and southeastern pastoral areas has improved. The declines in milk prices have increased milk access for market-dependent households as well. • Above average rainfall totals since mid-May have enabled the planting of long-cycle maize and sorghum and land preparation for short-cycle crops in most parts of the country except in the northeastern areas where the total Belg rainfall was below average. With normal to above normal June to September Kiremt rains forecast, the Meher crop performance is likely to be normal in these areas.