Beyond Modern Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UT Jazz Jury Repertoire – 5/2/06 Afternoon in Paris 43 a Foggy Day

UT Jazz Jury Repertoire – 5/2/06 Level 1 Tunes JA Level 2 Tunes JA Level 3 Tunes JA Level 4 Tunes JA Afternoon in Paris 43 A Foggy Day 25 Alone Together 41 Airegin 8 All Blues 50 A Night in Tunisia 43 Anthropology (Thrivin’ from a Riff) 6 Along Came Betty 14 A Time for Love 40 Afro Blue 64 Blue in Green 50 Beyond All Limits 9 Autumn Leaves 54 All the Things You Are 43 Body and Soul 41 Blood Count 66 Blue Bossa 54 Angel Eyes 23 Ceora 106 Bolivia 35 But Beautiful 23 Bird Blues (Blues 4 Alice) 2 Chelsea Bridge 66 Brite Piece 19 C Jam Blues 48 Bluesette 43 Children of the Night 33 Cherokee 15 Cantaloupe Island (96) 54 But Not for Me 65 Come Rain or Come Shine 25 Clockwise 35 Cantaloupe Island (132) 11 Cottontail 48 Confirmation 6 Countdown 28 Days of Wine and Roses 40 Don’t Get Around Much Anymore48 Corcovado-Quiet Nights 98 Dolphin Dance 11 Doxy (134) 54 Easy Living 52 Desafinado (184) 74 E.S.P. 33 Doxy (92) 8 Everything Happens to Me 23 Desafinado (136) 98 Giant Steps 28 Freddie the Freeloader 50 Footprints 33 Donna Lee 6 I'll Remember April 43 For Heaven’s Sake 89 Four 7 Embraceable You 51 Infant Eyes 33 Georgia 49 Groovin’ High 43 Estate 94 Inner Urge 108 Honeysuckle Rose 71 Have You Met Miss Jones 25 Fee Fi Fo Fum 33 It’s You or No One 61 I Got It Bad 48 Here’s That Rainy Day 23 Goodbye 94 Joshua 50 Impressions (112) 54 How Insensitive 98 I Can’t Get Started 25 Katrina Ballerina 9 Impressions (224) 28 I Didn’t Know About You 48 I Mean You 56 Lament for Booker 60 Killer Joe 70 I Hear a Rhapsody 80 In Case You Haven’t Heard 9 Love for -

How Democratic Is Jazz?

Accepted Manuscript Version Version of Record Published in Finding Democracy in Music, ed. Robert Adlington and Esteban Buch (New York: Routledge, 2021), 58–79 How Democratic Is Jazz? BENJAMIN GIVAN uring his 2016 election campaign and early months in office, U.S. President Donald J. Trump was occasionally compared to a jazz musician. 1 His Dnotorious tendency to act without forethought reminded some press commentators of the celebrated African American art form’s characteristic spontaneity.2 This was more than a little odd. Trump? Could this corrupt, capricious, megalomaniacal racist really be the Coltrane of contemporary American politics?3 True, the leader of the free world, if no jazz lover himself, fully appreciated music’s enormous global appeal,4 and had even been known in his youth to express his musical opinions in a manner redolent of great jazz musicians such as Charles Mingus and Miles Davis—with his fists. 5 But didn’t his reckless administration I owe many thanks to Robert Adlington, Ben Bierman, and Dana Gooley for their advice, and to the staffs of the National Museum of American History’s Smithsonian Archives Center and the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Copyright © 2020 by Benjamin Givan. 1 David Hajdu, “Trump the Improviser? This Candidate Operates in a Jazz-Like Fashion, But All He Makes is Unexpected Noise,” The Nation, January 21, 2016 (https://www.thenation.com/article/tr ump-the-improviser/ [accessed May 14, 2019]). 2 Lawrence Rosenthal, “Trump: The Roots of Improvisation,” Huffington Post, September 9, 2016 (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-the-roots-of-improv_b_11739016 [accessed May 14, 2019]); Michael D. -

8LJAIJ/1 Victoires Mull Changes 6 New Italian Dance Chart 7 Special: Jazz10 Off the Record26

Goddard Out At Kiss 4 GEMA Fees Up12% 5 8LJAIJ/1 Victoires Mull Changes 6 New Italian Dance Chart 7 Special: Jazz10 Off The Record26 Europe's Music Radio Newsweekly . Volume 8 . Issue 24 . June 15, 1991. 3, US$ 5, ECU 4 New Feature: RESEARCH BIDDING POOL GROWS M&M Debuts Nielsen To Bid For Jazz Page Jazz followers get a double treat Radio Contract this week in M&M, as we high- our media research resources here light the world of jazz music (see by Hugh Fielder page11)andlauncha new and we have also submitted an monthly page covering the jazz US broadcast research firm A. C. application for the JICNAR read- radio and record industries (see Nielsen has thrown its hat into ership contract." Last year the page 10). the ring for the new joint inde- company vied unsuccessfully for Coordinated by M&M chart pendent radio/BBC audience the BARB TV audience survey. reports manager and jazzafi- research contract (RAJAR). Nielsen joins a growing list of cionado Terry Berne, this new Nielsen UK media sales exec- biddersfortheproject. A monthly page will include airplay utive Lisa Rudman confirms, spokesperson for RSGB, which reports from jazz stations/presen- "We shall definitely be in the run- currently holds the JICRAR con - ters, Top 20 album sales,the THE BEST OF FRIENDS - Old friends Cliff Richard and popular ning. We have been building up (continueson page26) Most -PlayedAlbums,reviews, Yugoslav singer Alexander Mezek relax with Phonogram executives after station/presenterprofiles,label performing their single "To A Friend" (Mercury) on Germany's most popu- marketing/promotion activities, lar game show "Wetten Dass". -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

A Search and Retrieval Based Approach to Music Score Metadata Analysis

A Search and Retrieval Based Approach to Music Score Metadata Analysis Jamie Gabriel FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY SYDNEY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2018 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as part of the collaborative doctoral degree and/or fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This research is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program. Production Note: Signature: Signature removed prior to publication. _________________________________________ Date: 1/10/2018 _________________________________________ i ACKNOWLEGEMENT Undertaking a dissertation that spans such different disciplines has been a hugely challenging endeavour, but I have had the great fortune of meeting some amazing people along the way, who have been so generous with their time and expertise. Thanks especially to Arun Neelakandan and Tony Demitriou for spending hours talking software and web application architecture. Also, thanks to Professor Dominic Verity for his deep insights on mathematics and computer science and helping me understand how to think about this topic in new ways, and to Professor Kelsie Dadd for providing me with some amazing opportunities over the last decade. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

Roberto Miranda Dewey Johnson

ENCORE played all those instruments and he taught those taught me.” instruments to me and my brother. One of the Miranda recalls that he made his first recording at ROBERTO favorite memories I have of my life is watching my age 21 with pianist Larry Nash and drummer Woody parents dance to Latin music. Man! That still is an “Sonship” Theus, who were both just 16 at the time. incredible memory.” The name of the album was The Beginning and it also Years later in school, his brother played percussion featured saxophonists Herman Riley and Pony MIRANDA in concert band and Miranda asked for a trumpet. All Poindexter and trumpeter Luis Gasca (who, under those chairs were taken, he was told, so he requested contract elsewhere, used a pseudonym). The drummer by anders griffen a guitar, but was told that was not a band instrument. became a dear friend and was instrumental in Miranda They did need bass players, however, so that’s when he ending up on a record with Charles Lloyd (Waves, Bassist Roberto Miranda has been on many musical first played bass but gave it up after the semester. The A&M, 1972), even though, as it was happening, adventures, performing and recording with his brothers had formed a band together in which Louis Miranda didn’t even know he was being recorded. mentors—Horace Tapscott, John Carter and Bobby played drum set and Roberto played congas. As “Sonship Theus was a very close friend of mine. Bradford and later, Kenny Burrell—as well as artists teenagers they started a social club and held dances. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

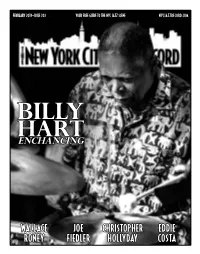

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

Eartrip7.Pdf Download

CONTENTS Editorial An internet-related rant and a summary of the delights to follow in the rest of the current issue. By David Grundy. [pp.3-4] Listening to Sachiko M 12,000 words (count' em) – a lengthy, and no-doubt futile attempt to get to grips with some of the recordings of empty-sampler player (or, in her own words, 'non-musician'), Sachiko M, including interminable ramblings on such albums as 'Bar Sachiko,' 'Filament 1', and 'Tears'. By David Grundy. [pp.5-26] The Drop at the Foot of the Ladder: Musical Ends and Meanings of Performances I Haven't Been To, Fluxus and Today 11,000 words (count 'em), covering the delicate and indelicate negotiations between music and performance, audience and performer, art and non-art, that take place in the 1960s works of Fluxus and their distant inheritors, Mattin and Taku Unami. By Lutz Eitel. [pp.27-52] Feature: Live in Seattle Two solo takes and a duo relating to Coltrane's 1965 recording, made at the breaking point of his 'Classic Quartet', poised between old and new, music that pushes at the limits and drops back only to push again with furious persistence. By David Grundy and Sean Bonney. [pp.53-74] Interview: The Rent To call The Rent a Steve Lacy 'tribute band' would be to do them an immense disservice, though their repertoire consists mainly of Lacy compositions. Their conversation with Ted Harms covers such topics as inter-disciplinarity, the Lacy legacy, and the notion of jazz repertoire. [pp.75-83] You Tube Watch: Billy Harper A feature devoted this issue to the great Texan tenor Billy Harper.