Eartrip7.Pdf Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Ensemble of Chicago Thelonious Sphere Monk

Art ensemble of chicago thelonious sphere monk Find a Art Ensemble Of Chicago* With Cecil Taylor - Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming Of The Masters Vol.2 first pressing or reissue. Complete your Art. Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters Series Vol. 2 is an album by the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Cecil Taylor released on the Japanese DIW. Art Ensemble of Chicago, Cecil Taylor - Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol.2 - Music. This CD promises much more than it delivers, appearing to be a tribute to Thelonious Monk that features the Art Ensemble of Chicago and guest pianist Cecil. Find album release information for Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol. 2 - The Art Ensemble of Chicago on AllMusic. Thelonious Sphere Monk - Dreaming of the Masters Vol. 2 Recorded in , at Systems Two Studios, Brooklyn. Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol. 2, an Album by Art Ensemble of Chicago With Cecil Taylor. Released in on (catalog no. CK Albuminformatie voor Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the masters ; vol.2 van Art Ensemble of Chicago. ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO WITH CECIL TAYLOR ~ Thelonious Sphere Monk - Dreaming Of The Masters Vol. 2 []. C'est comme un. Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol. 2 by The Art Ensemble of Chicago release on May 06, Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the. "Dreaming of the Masters"、"Intro to Fifteen"、"Excerpt from Fifteen, Pt. 3A" とその他を含む、アルバム「Thelonious Sphere Monk」の曲を聴こう。 . Acquista il CD album Thelonious Sphere Monk di Art Ensemble Of Chicago in offerta; album e dischi in vendita online a prezzi scontati su La Feltrinelli. -

The Rock of Our Salvation

THE ROCK OF OUR SALWATION: A TREATISE - RESPECTING THE NATURES, PERSON, OFFICES, WORK SUFFERINGS, AND GLORY OF JESUS CHRIST. BY WILLIAM S. PLUMER, D.D., LL.D. A Let us make a joyful noise to the Rock of our salvation. PSA. 95:1. PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY, 150 NASSAU-STREET, NEW YORK. ENTERED according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by the AMERICAN TRACT SoCIETY, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for - ern District of New York. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. CHRIST ALL IN ALL, page 7: opposed, 8, 17; his Names and Titles, 10–13; Christ much loved, 13; what God's People say of Him, 18, 19. CHAPTER II. • THE DIVINITY of CHRIST, 22: proven by his Names, 22, 23; by his Attributes, 23–28; by his Works, 28–34; by his Worship, 35–38; Inferences, 38–40. CHAPTER III. THE SoNSHIP or CHRIST, 41: above that of Angels, of Adam, of Believers, 41; not merely because supernaturally conceived, 42; or by Designation to Office, or by his Resurrection, 43; or by being Heir of all Things. He has the same Nature with the Father, his Sonship real and proper, 45; eternal, 48; more than Mediatorship, ineffable, 49; long held, 51; proven, 53–56. CHAPTER IV. THE INCARNATION of CHRIST, 58: how effected, 59; true, 61; made under the Law, 62; foretold by Prophets, 64; often declared, 65; incomprehensible, 67–76; at the Right Time, 69; a Great Event, 73; perpetual, 76; Inferences, 76–79. CHAPTER W. THE MEssIAHSHIP or JESUs oF NAZARETH, 80: expected, 80; proven, 82–95; Remarks, 95–99. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

The History of Women in Jazz in Britain

The history of jazz in Britain has been scrutinised in notable publications including Parsonage (2005) The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935 , McKay (2005) Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain , Simons (2006) Black British Swing and Moore (forthcoming 2007) Inside British Jazz . This body of literature provides a useful basis for specific consideration of the role of women in British jazz. This area is almost completely unresearched but notable exceptions to this trend include Jen Wilson’s work (in her dissertation entitled Syncopated Ladies: British Jazzwomen 1880-1995 and their Influence on Popular Culture ) and George McKay’s chapter ‘From “Male Music” to Feminist Improvising’ in Circular Breathing . Therefore, this chapter will provide a necessarily selective overview of British women in jazz, and offer some limited exploration of the critical issues raised. It is hoped that this will provide a stimulus for more detailed research in the future. Any consideration of this topic must necessarily foreground Ivy Benson 1, who played a fundamental role in encouraging and inspiring female jazz musicians in Britain through her various ‘all-girl’ bands. Benson was born in Yorkshire in 1913 and learned the piano from the age of five. She was something of a child prodigy, performing on Children’s Hour for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) at the age of nine. She also appeared under the name of ‘Baby Benson’ at Working Men’s Clubs (private social clubs founded in the nineteenth century in industrial areas of Great Britain, particularly in the North, with the aim of providing recreation and education for working class men and their families). -

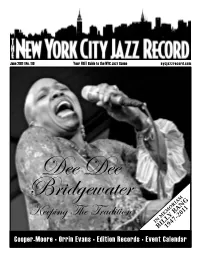

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Islam and Revolution

Imam Khomeini Islam and Revolution www.islamic-sources.com ISLAM and REVOLUTION 1 2 ISLAM and REVOLUTION Writings and Declarations of Imam Khomeini Translated and Annotated by Hamid Algar Mizan Press, Berkeley Contemporary Islamic Thought, Persian Series 3 Copyright © 1981 by Mizan Press All Rights Reserved Designed by Heidi Bendorf LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Khumayni, Ruh Allah. Islam and revolution. 1. Islam and state-Iran-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Iran-Politics and government-1941-1979-Addresses, essays, lectures. 3. Shiites-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Algar, Hamid. II. Title. ISBN 0-933782-04-7 hard cover ISBN 0-933782-03-9 paperback Manufactured in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS FOREWORD 9 INTRODUCTION BY THE TRANSLATOR 13 Notes 22 I. Islamic Government 1. INTRODUCTION 27 2. THE NECESSITY FOR ISLAMIC GOVERNMENT 40 3. THE FORM OF ISLAMIC GOVERNMENT 55 4. PROGRAM FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AN ISLAMIC GOVT. 126 Notes 150 II. Speeches and Declarations A Warning to the Nation/1941 169 In Commemoration of the Martyrs at Qum/ April 3, 1963 174 The Afternoon of ‘Ashura/June 3, 1963 177 The Granting of Capitulatory Rights to the U.S./ October27, 1964 181 Open Letter to Prime Minister Hoveyda/April 16, 1967 189 Message to the Pilgrims/February 6, 1971 195 The Incompatibility of Monarchy With Islam/ October 13, 1971 200 5 Message to the Muslim Students in North America/ July 10, 1972 209 In Commemoration of the First Martyrs of the Revolution/February 19, 1978 212 Message to the People of Azerbayjan/ -

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world. -

Vision Festival 21 Brochure

THE CREATIVE OPTION TOGETHER WE CONTINUE TO MAKE VISIONS REAL Our goal is to keep alive, in hearts and minds, the idealism, integrity and sense of responsibility that has inspired generations. We support the Present by remembering & respecting the Past & Prepare a Future where Improvisation and Freedom have a place. THIS IS ONLY POSSIBLE WITH YOUR HELP Charlotte Ka, ‘Dance a Celebration of Life’ Arts for Art presents Free Jazz as a sacred art-form, based in the Ideals of Freedom, Artist Info Page 24 Marcy Rosenblat, ‘Reveal’ Justice and Excellence. The art expresses our sense of hope and belief in the possibility of freedom, A Freedom to be our most unique self. So we push ourselves to do more, to redefine our self, our art and our communities. The music was built by self-determination. Where the artist defines, presents their work, not waiting for permission. Hope, Freedom, Self-determination are powerful ideas in any time, and particularly in this time. VISUAL ART AT VISION 21 AT ART VISUAL What we do or don’t do – does matter. We make a difference in our world and in our Lives by supporting what feeds our Souls. Bill Mazza, If the Vision Festival and the Work of Arts for Art feeds Souls then you should support it. ‘Vision 20, Day 5, Set 3, Wadada Leo Smith/Aruan Ortiz Duo’’ Our Humanity and Creativity needs a community of supporters who share our ideals. Jonas Hidalgo ENSURE ARTS FOR ART’S FUTURE ■ BE A MEMBER / DONATE TO ARTS FOR ART ■ BECOME ACTIVE IN THE AFA COMMUNITY Visit: www.artsforart.org/support or stop by the Arts for Art table at the Vision Festival. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

A Clear Apparance

A Clear Apparence 1 People in the UK whose music I like at the moment - (a personal view) by Tim Parkinson I like this quote from Feldman which I found in Michael Nyman's Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond; Anybody who was around in the early fifties with the painters saw that these men had started to explore their own sensibilities, their own plastic language...with that complete independence from other art, that complete inner security to work with what was unknown to them. To me, this characterises the music I'm experiencing by various composers I know working in Britain at the moment. Independence of mind. Independence from schools or academies. And certainly an inner security to be individual, a confidence to pursue one's own interests, follow one's own nose. I donʼt like categories. Iʼm not happy to call this music anything. Any category breaks down under closer scrutiny. Post-Cage? Experimental? Post-experimental? Applies more to some than others. Ultimately I prefer to leave that to someone else. No name seems all-encompassing and satisfying. So Iʼm going to describe the work of six composers in Britain at the moment whose music I like. To me itʼs just that: music that I like. And why I like it is a question for self-analysis, rather than joining the stylistic or aesthetic dots. And only six because itʼs impossible to be comprehensive. How can I be? Thereʼs so much good music out there, and of course there are always things I donʼt know. So this is a personal view. -

Keeping the Tradition by Marilyn Lester © 2 0 1 J a C K V

AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM P EE ING TK THE R N ADITIO DARCY ROBERTA JAMES RICKY JOE GAMBARINI ARGUE FORD SHEPLEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : ROBERTA GAMBARINI 6 by ori dagan [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : darcy james argue 7 by george grella General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : preservation hall jazz band 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ricky ford by russ musto Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : joe shepley 10 by anders griffen [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : weekertoft by stuart broomer US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 31 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Event Calendar 32 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mathieu Bélanger, Marco Cangiano, Ori Dagan, George Grella, George Kanzler, Annie Murnighan Contributing Photographers “Tradition!” bellowed Chaim Topol as Tevye the milkman in Fiddler on the Roof.