Dialects and Varieties in a Situation of Language Endangerment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures

( J WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU ,. PATTIMURA UNIVERSITY and THE SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS in cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE WORKPAPERS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 6 - MALUKU Nyn D. Laidig, Edi tor PAT'I'IMORA tJlflVERSITY and THE SUMMER IRSTlTUTK OP LIRGOISTICS in cooperation with 'l'BB DBPAR".l'MElI'1' 01' BDUCATIOII ARD CULTURE Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and cultures Volume 6 Maluku Wyn D. Laidig, Editor Printed 1989 Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia Copies of this publication may be obtained from Summer Institute of Linguistics Kotak Pos 51 Ambon, Maluku 97001 Indonesia Microfiche copies of this and other publications of the Summer Institute of Linguistics may be obtained from Academic Book Center Summer Institute of Linguistics 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road l Dallas, TX 75236 U.S.A. ii PRAKATA Dengan mengucap syukur kepada Tuhan yang Masa Esa, kami menyambut dengan gembira penerbitan buku Workpapers in Indonesian Languages , and Cultures. Penerbitan ini menunjukkan adanya suatu kerjasama yang baik antara Universitas Pattimura deng~n Summer Institute of Linguistics; Maluku . Buku ini merupakan wujud nyata peran serta para anggota SIL dalam membantu masyarakat umumnya dan masyarakat pedesaan khususnya Diharapkan dengan terbitnya buku ini akan dapat membantu masyarakat khususnya di pedesaan, dalam meningkatkan pengetahuan dan prestasi mereka sesuai dengan bidang mereka masing-masing. Dengan adanya penerbitan ini, kiranya dapat merangsang munculnya penulis-penulis yang lain yang dapat menyumbangkan pengetahuannya yang berguna bagi kita dan generasi-generasi yang akan datang. Kami ucapkan ' terima kasih kepada para anggota SIL yang telah berupaya sehingga bisa diterbitkannya buku ini Akhir kat a kami ucapkan selamat membaca kepada masyarakat yang mau memiliki buku ini. -

East Nusantara: Typological and Areal Analyses Pacific Linguistics 618

East Nusantara: typological and areal analyses Pacific Linguistics 618 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: John Bowden and I Wayan Arka (Managing Editors), Mark Donohue, Nicholas Evans, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Malcolm Ross, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson, and Darrell Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Marian Klamer, Universiteit Leiden Alexander Adelaar, University of Melbourne Harold Koch, The Australian National Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African University Studies Frantisek Lichtenberk, University of Byron Bender, University of Hawai‘i Auckland Walter Bisang, Johannes Gutenberg- John Lynch, University of the South Pacific Universität Mainz Patrick McConvell, Australian Institute of Robert Blust, University of Hawai‘i Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander David Bradley, La Trobe University Studies Lyle Campbell, University of Utah William McGregor, Aarhus Universitet James Collins, Universiti Kebangsaan Ulrike Mosel, Christian-Albrechts- Malaysia Universität zu Kiel Bernard Comrie, Max Planck Institute for Claire Moyse-Faurie, Centre National de la Evolutionary Anthropology Recherche Scientifique Soenjono Dardjowidjojo, Universitas Atma Bernd Nothofer, Johann Wolfgang Goethe- Jaya Universität Frankfurt am Main Matthew Dryer, State University of New York Bambang Kaswanti Purwo, Universitas Atma at Buffalo Jaya Jerold A. -

UNENGAGED BIBLELESS LANGUAGES (UBL List by Languages: ROL) September, 2018

UNENGAGED BIBLELESS LANGUAGES (UBL List by Languages: ROL) September, 2018. Version 1.0 Language ROL # Zones # Countries Country Lang. Population Anambé aan 1 1 Brazil 6 Pará Arára aap 1 1 Brazil 340 Aasáx aas 2 1 Tanzania 350 Mandobo Atas aax 1 1 Indonesia 10,000 Bankon abb 1 1 Cameroon 12,000 Manide abd 1 1 Philippines 3,800 Abai Sungai abf 1 1 Malaysia 500 Abaga abg 1 1 Papua New Guinea 600 Lampung Nyo abl 11 1 Indonesia 180,000 Abaza abq 3 1 Russia 37,800 Pal abw 1 1 Papua New Guinea 1,160 Áncá acb 2 2 Cameroon; Nigeria 300 Eastern Acipa acp 2 1 Nigeria 5,000 Cypriot Arabic acy 1 1 Cyprus 9,760 Adabe adb 1 1 Indonesia 5,000 Andegerebinha adg 2 1 Australia 5 Adonara adr 1 1 Indonesia 98,000 Adnyamathanha adt 1 1 Australia 110 Aduge adu 3 1 Nigeria 1,900 Amundava adw 1 1 Brazil 83 Haeke aek 1 1 New Caledonia 300 Arem aem 3 2 Laos; Vietnam 270 Ambakich aew 1 1 Papua New Guinea 770 Andai afd 1 1 Papua New Guinea 400 Defaka afn 2 1 Nigeria 200 Afro-Seminole Creole afs 3 2 Mexico; United States 200 Afitti aft 1 1 Sudan 4,000 Argobba agj 3 1 Ethiopia 46,940 Agta, Isarog agk 1 1 Philippines 5 Tainae ago 1 1 Papua New Guinea 1,000 Remontado Dumagat agv 3 1 Philippines 2,530 Mt. Iriga Agta agz 1 1 Philippines 1,500 Aghu ahh 1 1 Indonesia 3,000 Aizi, Tiagbamrin ahi 1 1 Côte d'Ivoire 9,000 Aizi, Mobumrin ahm 1 1 Côte d'Ivoire 2,000 Àhàn ahn 2 1 Nigeria 300 Ahtena aht 1 1 United States 45 Ainbai aic 1 1 Papua New Guinea 100 Amara aie 1 1 Papua New Guinea 230 Ai-Cham aih 1 1 China 2,700 Burumakok aip 1 1 Indonesia 40 Aimaq aiq 7 1 Afghanistan 701000 Airoran air 1 1 Indonesia 1,000 Ali aiy 2 2 Central African Republic; Congo Kinshasa 35,000 Aja (Sudan) aja 1 1 South Sudan 200 Akurio ako 2 2 Brazil; Suriname 2 Akhvakh akv 1 1 Russia 210 Alabama akz 1 1 United States 370 Qawasqar alc 1 1 Chile 12 Amaimon ali 1 1 Papua New Guinea 1,780 Amblong alm 1 1 Vanuatu 150 Larike-Wakasihu alo 1 1 Indonesia 12,600 Alutor alr 1 1 Russia 25 UBLs by ROL Page 1 Language ROL # Zones # Countries Country Lang. -

Languages of Indonesia (Maluku)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Maluku) Page 1 of 30 Languages of Indonesia (Maluku) See language map. Indonesia (Maluku). 2,549,454 (2000 census). Information mainly from K. Whinnom 1956; K. Polman 1981; J. Collins 1983; C. and B. D. Grimes 1983; B. D. Grimes 1994; C. Grimes 1995, 2000; E. Travis 1986; R. Bolton 1989, 1990; P. Taylor 1991; M. Taber 1993. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Maluku) is 132. Of those, 129 are living languages and 3 are extinct. Living languages Alune [alp] 17,243 (2000 WCD). 5 villages in Seram Barat District, and 22 villages in Kairatu and Taniwel districts, west Seram, central Maluku. 27 villages total. Alternate names: Sapalewa, Patasiwa Alfoeren. Dialects: Kairatu, Central West Alune (Niniari-Piru-Riring-Lumoli), South Alune (Rambatu-Manussa-Rumberu), North Coastal Alune (Nikulkan-Murnaten-Wakolo), Central East Alune (Buriah-Weth-Laturake). Rambatu dialect is reported to be prestigious. Kawe may be a dialect. Related to Nakaela and Lisabata-Nuniali. Lexical similarity 77% to 91% among dialects, 64% with Lisabata-Nuniali, 63% with Hulung and Naka'ela. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Central- Eastern, Central Malayo-Polynesian, Central Maluku, East, Seram, Nunusaku, Three Rivers, Amalumute, Northwest Seram, Ulat Inai More information. Amahai [amq] 50 (1987 SIL). Central Maluku, southwest Seram, 4 villages near Masohi. Alternate names: Amahei. Dialects: Makariki, Rutah, Soahuku. Language cluster with Iha and Kaibobo. Also related to Elpaputih and Nusa Laut. Lexical similarity 87% between the villages of Makariki and Rutah; probably two languages, 59% to 69% with Saparua, 59% with Kamarian, 58% with Kaibobo, 52% with Piru, Luhu, and Hulung, 50% with Alune, 49% with Naka'ela, 47% with Lisabata-Nuniali and South Wemale, 45% with North Wemale and Nuaulu, 44% with Buano and Saleman. -

Bibliography of Language and Language Use in North and Central

Bibliography of Language and Language Use In• North and Central Maluku Prepared by Gary Holton Southeast Asia Paper No. 40 Center for Southeast Asian Studies School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa February 1996 Copyright 1996 Southeast Asia Papers Published by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa Honolulu, HI 96822 All Rights Reserved. The Center for Southeast Asian Studies is pleased to make available, A Bibliography of Language and Lilnguage Use in North and Central Maluku, Southeast Asia Paper No. 40. In recent years, the number of University of Hawai'i Southeast Asia faculty and graduate students conducting research in eastern Indonesia has grown steadily. Gary Holton's detailed bibliography of the languages of this region was partially funded by the Center's Sago Project, a research program under the direction of University of Hawai'i anthropologist, P. Bion Griffin and supported by the Henry Luce Foundation. This publication will provide another valuable resource focusing on Maluku and add to those being produced by University of Hawai'i anthropologists, geographers, nutritionists, botanists and linguists. It will add an essential component to the ever increasing academic writings available on the region. INTRODUCTION In spite of the recent resurgence in scholarly interest in eastern Indonesia, the conception of Maluku as a linguistic area remains in its infancy. Though many excellent literature reviews and bibliographies have appeared (see index), none has attempted to specifically address linguistics or language. Polman's bibliographies (1981,1983) include chapters on language yet often overlook wordlists and references to language use which are buried in missionary and government publications from the colonial era. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 225 3=AUSTRONESIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector covers 72 sets of languages (1,179 outer languages, comprising 3,182 inner languages) spoken by predominantly island-dwelling communities, located from the western Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific and constituting the Austronesian intercontinental affinity. They extend more than half-way around the planet (eastwards from 43º E to 109º W; see note under phylozone 39=), and have also been associated with the languages of phylozone 47=Daic, within the "Austro-Tai" hypothesis. Zone 30= covers languages spoken on the island of Taiwan (Formosa), and zone 31= covers languages spoken by communities situated on most of the islands from the Philippines and the Celebes through Java, Southeast Asia (including Hainan island in China), Borneo and Sumatra to Madagascar: 30=TAIWANIC 31=HESPERONESIC Zones 32= to 39= cover languages spoken on most of the islands from the Nusa Tenggera archipelago through New Guinea and across the Pacific, as far as New Zealand / Aotearoa, French Polynesia and Hawaii: 32=MESONESIC 33=HALMAYAPENIC 34=NEOGUINEIC 35=MANUSIC 36=SOLOMONIC 37=KANAKIC 38=WESTPACIFIC 39=TRANSPACIFIC Before consulting the following tables, please see Guide to the Register in Volume One Les données supplémentaires -

J. Collins a Note on Cultural Vocabulary in the Moluccan Islands

J. Collins A note on cultural vocabulary in the Moluccan Islands In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 139 (1983), no: 2/3, Leiden, 357-362 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 06:16:58PM via free access KORTE MEDEDELINGEN JAMES T. COLLINS, UNIVERSITI KEBANGSAAN MALAYSIA l A NOTE ON CULTURAL VOCABULARY IN THE MOLUCCAN ISLANDS In recent years M. A. Chlenov has played a unique and important role in Austronesian linguistics. In his writings (1973,1976) he has made available some of the results and data of his extensive field work in East Indonesia. His stimulating article (1980) represents still an- other contribution reflecting a familiarity with a number of diverse languages as wel1 as a deep humanistic concern with extracting relevant conclusions from such a diversity. It is certainly not the intention of this brief note to discourage these efforts or to disparage such a wide knowledge. On the contrary, Dr. Chlenov's work remains of permanent importance in Moluccan linguistic studies. Nonetheless, it is appro- priate to comment on the procedure and some of the examples in his most recent article. Consideration of this procedure may benefit our attempts at reconstructing proto-languages and discovering the outlines of ancient cultures. There is an implicit methodology employed by Chlenov in sepa- rating Austronesian from non Austronesian vocabulary. Confronted by a large amount of data, apparently his first step was to group seemingly related words together. There followed a search for possible cognates in other languages and in reconstructed proto-languages. -

Learning and Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today

Learning & Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today Final Learning & Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today Aichi 2.indd 1 28/2/09 18:02:45 This book should be cited as: UNESCO, 2009, Learning and Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today. Edited by P. Bates, M. Chiba, S. Kube & D. Nakashima, UNESCO: Paris, 128 pp. This publication is a collaborative effort of: The Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, Natural Sciences Sector The Intangible Heritage Section, Culture Sector The Division of Cultural Policies and Intercultural Dialogue, Culture Sector Acknowledgements Ken-ichi Abe, Japan Centre for Area Studies, Osaka National Museum of Ethnology, Japan Claudia Benavides, Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, Natural Sciences Sector, UNESCO Noriko Iizuka, Japan Centre for Area Studies, Osaka National Museum of Ethnology, Japan Tetsuya Inamura, Professor, Aichi Prefectural University, Nagoya, Japan Wil de Jong, Japan Centre for Area Studies, Osaka National Museum of Ethnology, Japan Anahit Minasyan, Endangered Languages Programme, Intangible Heritage Section, Culture Sector, UNESCO Annette Nilsson, Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, Natural Sciences Sector, UNESCO Susanne Schnuttgen, Division of Cultural Policies and Intercultural Dialogue, Culture Sector, UNESCO Editors Peter Bates, Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, Natural Sciences Sector, UNESCO Moe Chiba, Division of Cultural Policies and Intercultural Dialogue, Culture Sector, UNESCO Sabine Kube, Endangered -

Missing Languages

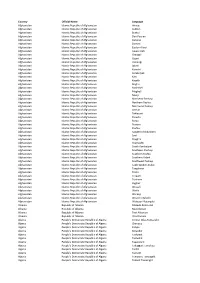

Country Official Name Language Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Aimaq Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ashkun Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Brahui Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Dari Persian Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Darwazi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Domari Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Eastern Farsi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Gawar-Bati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Grangali Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Gujari Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Hazaragi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Jakati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kamviri Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Karakalpak Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kazakh Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kirghiz Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Malakhel Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Mogholi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Munji Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northeast Pashayi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northern Pashto Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northwest Pashayi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ormuri Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Pahlavani Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Parachi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Parya Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Prasuni Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan -

Some Principles on the Use of Macro-Areas in Typological Comparison

Language Dynamics and Change 4 (2014) 167–187 brill.com/ldc Some Principles on the Use of Macro-Areas in Typological Comparison Harald Hammarström Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics & Centre for Language Studies, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, The Netherlands [email protected] Mark Donohue Department of Linguistics, Australian National University, Australia [email protected] Abstract While the notion of the ‘area’ or ‘Sprachbund’ has a long history in linguistics, with geographically-defined regions frequently cited as a useful means to explain typolog- ical distributions, the problem of delimiting areas has not been well addressed. Lists of general-purpose, largely independent ‘macro-areas’ (typically continent size) have been proposed as a step to rule out contact as an explanation for various large-scale linguistic phenomena. This squib points out some problems in some of the currently widely-used predetermined areas, those found in the World Atlas of Language Struc- tures (Haspelmath et al., 2005). Instead, we propose a principled division of the world’s landmasses into six macro-areas that arguably have better geographical independence properties. Keywords areality – macro-areas – typology – linguistic area 1 Areas and Areality The investigation of language according to area has a long tradition (dating to at least as early as Hervás y Panduro, 1971 [1799], who draws few historical © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2014 | doi: 10.1163/22105832-00401001 168 hammarström and donohue conclusions, or Kopitar, 1829, who is more interested in historical inference), and is increasingly seen as just as relevant for understanding a language’s history as the investigation of its line of descent, as revealed through the application of the comparative method.