A Re- Evaluation of the Romano-British Period in Cumbria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – Issues of National Identity and Proto-Celtic Substratum

Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – issues of national identity and Proto-Celtic substratum Silvana Trombetta1 Laboratory of Provincial Roman Archeology (MAE/USP) [email protected] Received: 03/29/2018 Approved: 04/30/2018 Abstract : The object of this article is to discuss the presence of the Castro Culture and of Celtic people on the Iberian Peninsula. Currently there are two sides to this debate. On one hand, some consider the “Castro” people as one of the Celtic groups that inhabited this part of Europe, and see their peculiarity as a historically designed trait due to issues of national identity. On the other hand, there are archeologists who – despite not ignoring entirely the usage of the Castro culture for the affirmation of national identity during the nineteenth century (particularly in Portugal) – saw distinctive characteristics in the Northwest of Portugal and Spain which go beyond the use of the past for political reasons. We will examine these questions aiming to decide if there is a common Proto-Celtic substrate, and possible singularities in the Castro Culture. Keywords : Celts, Castro Culture, national identity, Proto-Celtic substrate http://ppg.revistas.uema.br/index.php/brathair 39 Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 There is marked controversy in the use of the term Celt and the matter of the presence of these people in Europe, especially in Spain. This controversy involves nationalism, debates on the possible existence of invading hordes (populations that would bring with them elements of the Urnfield, Hallstatt, and La Tène cultures), and the possible presence of a Proto-Celtic cultural substrate common to several areas of the Old Continent. -

Introduction to Roman Yorkshire

ROMAN YORKSHIRE: PEOPLE, CULTURE, LANDSCAPE By Patrick Ottaway. Published 2013 by The Blackthorn Press Chapter 1 Introduction to Roman Yorkshire ‘In the abundance and variety of its Roman antiquities, Yorkshire stands second to no other county’ Frank and Harriet Wragg Elgee (1933) The Yorkshire region A Roman army first entered what we now know as Yorkshire in about the year AD 48, according to the Roman author Cornelius Tacitus ( Annals XII, 32). This was some five years after the invasion of Britain itself ordered by the Emperor Claudius. The soldiers’ first task in the region was to assist in the suppression of a rebellion against a Roman ally, Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes, a native people who occupied most of northern England. The Roman army returned to the north in about the years 51-2, once again to support Cartimandua who was, Tacitus tells us, now under attack by her former consort, a man named Venutius ( Annals XII, 40). In 69 a further dispute between Cartimandua and Venutius, for which Tacitus is again the (only) source, may have provided a pretext for the Roman army to begin the conquest of the whole of northern Britain ( Histories III, 45). England south of Hadrian’s Wall, including Yorkshire, was to remain part of the Roman Empire for about 340 years. The region which is the principal subject of this book is Yorkshire as it was defined before local government reorganisation in 1974. There was no political entity corresponding to the county in Roman times. It was, according to the second century Greek geographer Ptolemy, split between the Brigantes and the Parisi, a people who lived in what is now (after a brief period as Humberside) the East Riding. -

The Multiple Estate: a Framework for the Evolution of Settlement in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian Cumbria

THE MULTIPLE ESTATE: A FRAMEWORK FOR THE EVOLUTION OF SETTLEMENT IN ANGLO-SAXON AND SCANDINAVIAN CUMBRIA Angus J. L. Winchester In general, it is not until the later thirteenth century that surv1vmg documents enable us to reconstruct in any detail the pattern of rural settlement in the valleys and plains of Cumbria. By that time we find a populous landscape, the valleys of the Lake District supporting communi ties similar in size to those which they contained in the sixteenth century, the countryside peppered with corn mills and fulling mills using the power of the fast-flowing becks to process the produce of field and fell. To gain any idea of settlement in the area at an earlier date from documentary sources, we are thrown back on the dry, bare bones of the structure of landholding provided by a scatter of contemporary documents, including for southern Cumbria a few bald lines in the Domesday survey. This paper aims to put some flesh on the evidence of these early sources by comparing the patterns of lordship which they reveal in different parts of Cumbria and by drawing parallels with other parts of the country .1 Central to the argument pursued below is the concept of the multiple estate, a compact grouping of townships which geographers, historians and archaeologists are coming to see as an ancient, relatively stable framework within which settlement in northern England evolved during the centuries before the Norman Conquest. The term 'multiple estate' has been coined by G. R. J. Jones to describe a grouping of settlements linked -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Farmers. Dixon William, Joiner and Cartwright, Pelutho Anderson J Oseph (Hind), N Ewtown Edmondson Wm., Grocer, Provision Dealer, Ham Anm;Trong Mrs

• • 224 NORTHERN OR ESKDALE PARLIAMENTARY DIVISION. Akeshaw, that is, Oakwood, is situated on the north bank of the Crummock Beck, five miles from the Abbey. At Overby is a small Reading Room and Library containing about fifty volumes, established in 1897. CHARITIES. The late John Longcake, Esq., of Pelutho, left by will in 1873 the interest of £600 to the poor cottagers of this parish, and the residue of his estate, after the payment of certain legacies, he ordered to be invested in the names of seven trustees, and the interest thereof to be devoted to the promotion of religion and education in the townships of Holme Abbey, Holme Low, and Holme St. Cuthbert's. " The testator bequeaths to the incumbent and church wardens of Holme St. Cuthbert's, a scholarship of £40, for three years, to assist any clever boy attending the school, in obtaining a higher education, and to the incumbent and churchwardens of Holme Abbey £10 for Aldoth School; £20 to the Abbey School; and to the incumbent and wardens of St. Paul's, for Silloth School, £20 per annum, to assist any deserving boy, and the trustees are directed that within twelve months after his death to set apart, and transfer into the names of the several incumbents sufficient Government stock as wo11ld answer the several endowments. The sum of £14 18s. is distributed annually to the poor. HOLME ST. CUTHBERTS. School Board--William Edmondson, chairman; Robert Biglands, John Ostle, Joseph Osbome, Tom Beaty. Clerk to the Board G. Wood Turney, solicitor, Maryport. Post Office at William Edmondson's, Mawbray. -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

1 Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia

Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia: Late Iron Age – Second Century AD Jonathan Wynne Rees Thesis submitted in requirement of fulfilments for the degree of Ph.D. in Archaeology, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London University of London 2012 1 I, Jonathan Wynne Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changes which occurred in the cultural landscapes of northwest Iberia, between the end of the Iron Age and the consolidation of the region by both the native elite and imperial authorities during the early Roman empire. As a means to analyse the impact of Roman power on the native peoples of northwest Iberia five study areas in northern Portugal were chosen, which stretch from the mountainous region of Trás-os-Montes near the modern-day Spanish border, moving west to the Tâmega Valley and the Atlantic coastal area. The divergent physical environments, different social practices and political affinities which these diverse regions offer, coupled with differing levels of contact with the Roman world, form the basis for a comparative examination of the area. In seeking to analyse the transformations which took place between the Late pre-Roman Iron Age and the early Roman period historical, archaeological and anthropological approaches from within Iberian academia and beyond were analysed. From these debates, three key questions were formulated, focusing on -

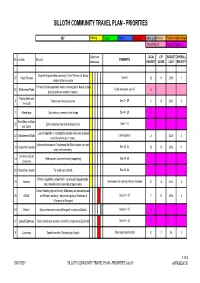

Item 09 Appendix Silloth

SILLOTH COMMUNITY TRAVEL PLAN - PRIORITIES KEY Walking Cycling Public T Car/Safety Other (n/a) Funded Transfer to other budget Linked Request Duplicate Requests Objectives LOCAL LTP BUDGET OVERALL NoLocation Request COMMENTS addressed PRIORITY SCORE COST PRIORITY Request for pedestrian crossing at Hylton Terrace for School 27 Hylton Terrace See 50 20 11 £15k 1 children & library people Primary School desperately needs crossing patrol. Needs to be a 50 Skinburness Road To be assessed - see 27 4 priority before an accident happens. Playing fields and 8 Pedestrian crossing required See 7 + 29 3 12 £12k 2 The Croft 7 After bridge Drop kerb on pavement after bridge See 8 + 29 32 Post Office and Spar 29 Zebra crossings from and to playing field. See 7 + 8 5 and Crofts Lack of footpaths. If no footpaths possible some sort of speed 32 Blitterlees to Silloth Land required 2 £20k 3 restrictions to be put in place. Continued from oppsite Tanglewood the Silloth people can walk 24 Footpath to Cemetery See 28, 44 13 12 £15k 4 safely to the cemetery. Cemetery at East 44 Path required (accidents nearly happening) See 24, 28 Causeway 28 Footpath to Cemetery To avoid early arrivals See 24, 44 Difficult negotiating wheelchairs - not enough dropped kerbs - 18 General Enforcement of existing Police & Allerdale 21 13 £10k 5 also motorists park across the dropped kerbs. Current flooding signs at Allonby & Mawbray are ignored becaus 26 B5300 are left open too long + advanced signing at Greenrow & See 33 + 47 7 9 £16k 6 Ellengrove at Maryport 33 Dubmill Sign to show when road to Maryport is closed at Dubmill. -

Ap P E N D Ix 1 P U B D E Ta

Appendix 1 Pub DetailsPub Page 30 Appendix 2 Previous Landlords Date Publicans and other details 1847 Joseph Messenger Henry Osborne 1851 Margaret Roper 1858 Henry Bishop 1883 1897 Sarah Bishop 1901 Sophie Rome 1906 John Kendal 1910 John Creighton 1914 John Kendal 1924 Albert Collister 1929 Tom Graham – Blacksmith 1934 / 1938 / 1954 1968 Gilbert & Elsie Harrison (daughter of Tom Graham) 1975 H Kirkbride 1976 Tom & Elsie Pigg 2004 Landlady Elsie Pigg died. Pub shut for 18 months 2005 Oct 22 1st Public Meeting, 56 attend incl Mandy Hodgson (Elsie’s niece who inherited the pub). 2005 Dec Hopes Estate Agents advertise pub for sale £350,000 2006 Apr Independent Valuation £175,000 2006 Jun Hopes disengaged. New Agents, Bar Agency, instructed to sell pub for £299,000 2006 Aug Offer made by Dawn Lindsay & Andrew Mattinson. Pub bought close to asking price 2006 Dec Pub reopens 2012 Pub closed and up for sale 2013 Dec Morven & Jay Anson buy pub. £95,000. Rename ‘The Lowther. Village Pub and Dining’ 2014 Jul Pub opens after refurbishment 2018 Jan Pub discreetly placed on market with Sidney Phillips May Stop serving food Dec 23 Pub Closes 2019 Mar 30 Application for Change of Use to a dwelling May 16 Parish Council Meeting to discuss the pub May 26 First Public Meeting and Public Consultation June 23 Lowther Arms Community Project formed. Jul 11 Allerdale BC suggest Jay & Morven Anson withdraw planning application Jul 18 LACP accepted onto Plunkett Foundation ‘More Than A Pub’ (MTAP) programme Jul 20 Parish Council apply for Asset of Community Value (ACV) Jul 30 ACV granted by Allerdale BC. -

Cumberland. L"Lpha

DIRECTORY.] CUMBERLAND. L"LPHA. 261 Flekher Isaac, butcher & fanner 1Blacklock Joseph, grocer &; !mb-post- Clark John, farmer ..HM'kel' Sa.rah J ane (Mrs.), stahoner master Dinwoodie David, farmer, Threapland ~ lIuh-flo1\tu.listl'ess BI,)"V'"n J ames, grocer & tailor Edmonds SI. frmr. Threapland-Lees :Highmoor William, shopkeeper Cape, Joseph, yeoman, Kirkland Ferguson Richard, farmer, Overgates Ismay JamBs, King's Arms P.B. AI; , Dixan Edward, farmer Flemingo Thomas, farmer, Threapland fa.rmer, Low Wood Nook Hanvey William, boot maker Flf'tchE'r Robinson, farmer,Low Fields .Little John, blacksmith Hayton Isaac, farmer Foster William, fanner Little Willi.am, assistant overseer & I Highmoor Sarah (Mrs.), farmer Gilbanks Eleanor (Miss), shopkeeper blacksmith Littleton Thomas, farmer, Fitz farm Graham Richard, farmer, Threapland Rome John James, farmer Mann Thomas, farmer Graham William George, boot maker &ott Thas. & Sons, farmers,Whitrigg -Miller Jane (Mrs.), farmer Graham Wilson, farmer, Threapland Smallwood Geo. farmer,Whitrigg hall Moore Robert, grocer Ha-rryman Jonathan, yeoman ,Wilson Mary (Miss), Sun inn IPattinson John, farmer Henderson Wm. farmer, Threapland Redpath Thos. Smith, market grdnr Hill J oseph, farmer, Bothel BEWALDETH. Robinson Thos. carpenter & joiner Hope George, blacksmith, cycle Letters through Mealsgate 8.0. Robinson William, builder agent &; sub-postmaster -Railton Ernest Hy. e~. Snittlegarth Tiffin Edward, farmer Horn William, farmer, Bothel (postal address,Ireby,Ylealsgate S.O J ohnstone John Wise, grocer COMMERCIAL. BOTHEL. Lowss Hy. Fearon, butcher & farmer Allinson .J~seph, farmer, ~igg- Wood PRIVATE RESIDENTS. MElfston George, farmer, Bothel Bran Wilham, farmer, High Honses i • McGuffie J ames,Greyhound beerhouse l'attinson WiUiam farmer 'Armstrong MIss Maxwell Thos. -

Allerdale Borough Council Rural Settlement List

ALLERDALE BOROUGH COUNCIL RURAL SETTLEMENT LIST In accordance with Schedule 1 of the Local Government and Rating Act 1997 the following shall be the Rural Settlement List for the Borough of Allerdale. Rural Area Rural Settlement Above Derwent Braithwaite Thornthwaite Portinscale Newlands Stair Aikton Aikton Thornby Wiggonby Allerby & Oughterside Allerby Prospect Oughterside Allhallows Baggrow Fletchertown Allonby Allonby Aspatria Aspatria Bassenthwaite Bassenthwaite Bewaldeth & Snittlegarth Bewaldeth Snittlegarth Blennerhasset & Torpenhow Blennerhasset Torpenhow Blindbothel Blindbothel Mosser Blindcrake Blindcrake Redmain Boltons Boltongate Mealsgate Bolton Low Houses Borrowdale Borrowdale Grange Rosthwaite Bothel & Threapland Bothel Threapland Bowness Anthorn Bowness on Solway Port Carlisle Drumburgh Glasson Bridekirk Bridekirk Dovenby Tallentire Brigham Brigham Broughton Cross Bromfield Blencogo Bromfield Langrigg Broughton Great Broughton Little Broughton Broughton Moor Broughton Moor Buttermere Buttermere Caldbeck Caldbeck Hesket Newmarket Camerton Camerton Crosscanonby Crosscanonby Crosby Birkby Dean Dean Eaglesfield Branthwaite Pardshaw Deanscales Ullock Dearham Dearham Dundraw Dundraw Embleton Embleton Gilcrux Gilcrux Bullgill Great Clifton Great Clifton Greysouthen Greysouthen Hayton & Mealo Hayton Holme Abbey Abbeytown Holme East Waver Newton Arlosh Holme Low Causewayhead Calvo Seaville Holme St Cuthbert Mawbray Newtown Ireby & Uldale Ireby Uldale Aughertree Kirkbampton Kirkbampton Littlebampton Kirkbride Kirkbride Little Clifton -

Brae Rigg, Oughterby, Carlisle Offers in the Region of £220,000 Oughterby, Carlisle

Brae Rigg, Oughterby, Carlisle Offers in the region of £220,000 Oughterby, Carlisle Offers in the region of £220,000 DESCRIPTION Modern detached house with fantastic views to the surrounding countryside and the Scottish Hills in the distance. The property benefits from an oil fired central heating system and double glazing and the accommodation comprises to the ground floor entrance hall, cloakroom/wc, through lounge, conservatory, kitchen/dining room, utility room and to the first floor there are three bedrooms and a modern bathroom/wc. To the outside there are gardens to the front and rear, a drive and garage. Viewing is recommended to appreciate the presentation and the location. EPC rating grade is D. A copy of the certificate will be available for inspection upon request. LOCATION The hamlet of Oughterby is approximately 1.5 miles from the village of Kirkbampton and approximately 3 miles from the village of Kirkbride and the Solway coast, approximately 6 miles from the market town of Wigton and approximately 7 miles from the border city of Carlisle. Within Kirkbampton there is a school and within Kirkbride there is a shop/post office, school, doctors surgery and bowling/tennis club. Both Carlisle and Wigton provide a wider range of social and retail amenities. From Wigton there are road and rail links to east and west Cumbria. Oughterby is also approximately 12 miles from the fringe of the Lake District National Park an area of outstanding natural beauty and approximately 6 miles from the Carlisle by-pass road which links with the M6 motorway. DIRECTIONS If travelling from Carlisle, take the B5307 towards Kirkbampton then follow the signs for Oughertby.