Introduction to Roman Yorkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Annals of the Caledonians, Picts and Scots

Columbia (HnitJer^ftp intlifCttpufUmigdrk LIBRARY COL.COLL. LIBRARY. N.YORK. Annals of t{ie CaleDoiuans. : ; I^col.coll; ^UMl^v iV.YORK OF THE CALEDONIANS, PICTS, AND SCOTS AND OF STRATHCLYDE, CUMBERLAND, GALLOWAY, AND MURRAY. BY JOSEPH RITSON, ESQ. VOLUME THE FIRST. Antiquam exquirite matrem. EDINBURGH PRINTED FOR W. AND D. LAING ; AND PAYNE AND FOSS, PALL-MALL, LONDON. 1828. : r.DiKBURnii FIlINTEn I5Y BAI.LANTTNK ASn COMPAKV, Piiiri.'S WOKK, CANONGATK. CONTENTS. VOL. I. PAGE. Advertisement, 1 Annals of the Caledonians. Introduction, 7 Annals, -. 25 Annals of the Picts. Introduction, 71 Annals, 135 Appendix. No. I. Names and succession of the Pictish kings, .... 254 No. II. Annals of the Cruthens or Irish Picts, 258 /» ('^ v^: n ,^ '"1 v> Another posthumous work of the late Mr Rlt- son is now presented to the world, which the edi- tor trusts will not be found less valuable than the publications preceding it. Lord Hailes professes to commence his interest- ing Annals with the accession of Malcolm III., '* be- cause the History of Scotland, previous to that pe- riod, is involved in obscurity and fable :" the praise of indefatigable industry and research cannot there- fore be justly denied to the compiler of the present volumes, who has extended the supposed limit of authentic history for many centuries, and whose labours, in fact, end where those of his predecessor hegi7i. The editor deems it a conscientious duty to give the authors materials in their original shape, " un- mixed with baser matter ;" which will account for, and, it is hoped, excuse, the trifling repetition and omissions that sometimes occur. -

Playing Purple in Avalon Hill Britannia

Sweep of History Games Magazine #2 Page 1 Sweep of History Games Magazine #2, Spring 2006. Published and edited by Dr. Lewis Pulsipher, [email protected]. This approximately quarterly electronic magazine is distributed free via http://www.pulsipher.net/sweepofhistory/index.htm, and via other outlets. The purpose of the magazine is to entertain and educate those interested in games related to Britannia ("Britannia-like games"), and other games that cover a large geographical area and centuries of time ("sweep of history games"). Articles are copyrighted by the individual authors. Game titles are trademarks of their respective publishers. As this is a free magazine, contributors earn only my thanks and the thanks of those who read their articles. This magazine is about games, but we will use historical articles that are related to the games we cover. This copyrighted magazine may be freely distributed (without alteration) by any not-for-profit mechanism. If you are in doubt, write to the editor/publisher. The “home” format is PDF (saved from WordPerfect); it is also available as unformatted HTML (again saved from WP) at www.pulsipher.net/sweepofhistory/index.htm. Table of Contents strategy article in Issue 1, is one of the “sharks” from the World Boardgaming Championships. 1 Introduction Nick has twice won the Britannia tournament 1 Playing Purple in Avalon Hill there, and is also (not surprisingly) successful at Britannia by Nick Benedict WBC Diplomacy. 7 Britannia by E-mail by Jaakko Kankaanpaa 11 Review of game Mesopotamia: I confess, I’m fascinated to see what strategies the “sharks” will devise for the Second Edition, which by George Van Voorn Birth of Civilisation I understand will be used at this year’s 12 Trying to Define Sweep of History tournament. -

Churches with Viking Stone Sculpture 53

Durham E-Theses Early ecclesiastical organization:: the evidence from North-east Yorkshire Kroebel, Christiane How to cite: Kroebel, Christiane (2003) Early ecclesiastical organization:: the evidence from North-east Yorkshire, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3183/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Albstnllct Christiane Kroebel Early Ecclesiastical Organisation: the Evidence from North-east Yorkshire MA Thesis, University of Durham, Department of History, 2003 The aim of this thesis is to discover how parishes evolved in North-east Yorkshire. It seeks the origin ofthe parish system in the 7th century with the establishment of monasteria in accordance with the theory, the 'minster' hypothesis, that these were the minsters of the Middle Ages and the ancient parish churches of today. The territory of the monasterium, its parochia, was that of the secular royal vill, because kings granted these lands with the intention that monasteries provided pastoral care to the royal vill. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

~ 170 ~ 8. Bibliography

Peat exploitation on Thorne Moors. A case- study from the Yorkshire-Lincolnshire border 1626-1963, with integrated notes on Hatfield Moors Item Type Thesis Authors Limbert, Martin Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 28/09/2021 03:56:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/5454 8. BIBLIOGRAPHY Anon. (1867) Handbook for Travellers in Yorkshire. London: John Murray. Anon. [1876] The Life and Eccentricities of Lionel Scott Pilkington, alias Jack Hawley, of Hatfield, near Doncaster. Doncaster: Edward Dale, Free Press Office. Anon. (1885) Turf-bedding. Chambers’s Journal 2 (Fifth Series): 535-536. Anon. (1900) Peat as a Substitute for Coal. The Colliery Guardian, and Journal of the Coal and Iron Trades 80: 373. Anon. (1907) The Ziegler System of Peat Utilisation. Engineering 84: 671-675. Anon. [1946] The Process of Warping. In: Goole Rural District. The Official Handbook. Guide No. 121. London: Pyramid Press. Anon. (1949) Horticultural Peat. Sport and Country 187: 39-41. Anon. [1993] Thorne Landowners & Tenants 1741. Thorne Local History Society Occasional Papers No.13. [Appleton, E.V.] (1954) Report of the Scottish Peat Committee. 31 July 1953. House of Lords Papers and Bills No. 49-393. Scottish Home Department. Edinburgh: HMSO. Ashforth, P., Bendall, I. -

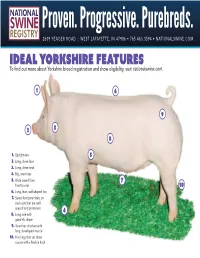

Yorkshire Features to find out More About Yorkshire Breed Registration and Show Eligibility, Visit Nationalswine.Com

Proven. Progressive. Purebreds. 2639 YEAGER ROAD :: WEST LAFAYETTE, IN 47906 • 765.463.3594 • NATIONALSWINE.COM Ideal yorkshire Features To find out more about Yorkshire breed registration and show eligibility, visit nationalswine.com. 1 6 9 2 3 8 1. Upright ears 5 2. Long, clean face 3. Long, clean neck 4. Big, even toes 5. Wide based from 7 front to rear 10 6. Long, lean, well-shaped top 7. Seven functional teats on each side that are well spaced and prominent 4 8. Long side with good rib shape 9. Good hip structure with long, developed muscle 10. Hind legs that set down square with a flexible hock Yorkshire AMERICA’S MATERNAL BREED Yorkshire boars and gilts are utilized as Grandparents (GP) in the production of F1 parent stock females that are utilized in a ter- minal crossbreeding program. They are called “The Mother Breed” and excel in litter size, birth and weaning weight, rebreeding interval, durability and longevity. They produce F1 females that exhibit 100% maternal heterosis when mated to a Landrace. Yorkshire breeders have led the industry in utilization History of the Yorkshire Breed of the "STAGES™" genetic evaluation program. From Yorkshires are white in color and have erect ears. They are 1990-2006, Yorkshire breeders submitted over 440,000 the most recorded breed of swine in the United States growth and backfat records and over 320,000 sow and in Canada. They are found in almost every state, productivity records. This represents the largest source with the highest populations being in Illinois, Indiana, of documented performance records in the world. -

Ripon City Plan Submission Draft

Submission Draft Plan Supporting Document D Supporting the Ripon Economy Ripon City Plan Submission Draft Supporting Document: Supporting the Ripon Economy March 2018 Submission Draft Plan Supporting Document D Supporting the Ripon Economy Contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 1 2 National Planning Context .................................................................................................. 2 2.1 National Planning Policy Framework................................................................................. 2 2.2 Planning Practice Guidance ............................................................................................... 4 3 Local Planning Authority Context ........................................................................................ 9 3.1 Harrogate District Local Plan – February 2001 (Augmented Composite) ......................... 9 3.2 Harrogate District Local Development Framework – Core Strategy ............................... 16 3.3 Harrogate District Local Plan: Draft Development Management Policies ...................... 21 3.4 Harrogate District Draft Local Plan .................................................................................. 23 4 Ripon City Plan Vision and Objectives ............................................................................... -

The Industrial Archaeology of West Yorkshire

The Industrial Archaeology of West Yorkshire Introduction: The impact of the Industrial Revolution came comparatively late to the West Yorkshire region. The seminal breakthroughs in technology that were made in a variety of industries (e.g. coal mining, textile, pottery, brick, and steam engine manufacture) during the 17th and 18th centuries, and the major production centres that initially grew up on the back of these innovations, were largely located elsewhere in the country. What distinguishes Yorkshire is the rate and density at which industry developed in the region from the end of the 18th century. This has been attributed to a wide variety of factors, including good natural resources and the character of the inhabitants! The portion of the West Riding north and west of Wakefield had become one of most heavily industrialised areas in the Britain by the end of the 19th century. It was also one of the most varied - there were some regional specialities, but at one time or another Yorkshire manufacturers supplied everything from artificial manure to motorcars. A list of local products for the 1890s would run into hundreds of items. Textile Manufacturing: The most prominent industry in the region has always been textile manufacture. There was a long tradition in the upland areas of the county of cloth production as a home-based industry, which supplemented farming. The scale of domestic production could hardly be considered negligible - the industry in Calderdale was after all so large that in 1779 it produced the Piece Hall in Halifax as an exchange centre and market. However, the beginnings of the factory system, and the birth of modern textile mills, dates to the introduction of mass-production techniques for carding and spinning cotton. -

Defra Statistics: Agricultural Facts – Yorkshire & the Humber

Defra statistics: Agricultural facts – Yorkshire & the Humber (commercial holdings at June 2019 (unless stated) The Yorkshire & the Humber region comprises the East Riding, Kingston upon Hull, N & NE Lincolnshire, City of York, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire. Parts of the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Parks are within the region. For the Yorkshire & the Humber region: Total Income from Farming increased by 26% between 2015 and 2019 to £452 million. The biggest contributors to the value of the output (£2.5 billion), which were pigs for meat (£382 million), wheat (£324 million), poultry meat (£267 million) and milk (£208 million), together account for 48%. (Sourced from Defra Aggregate agricultural accounts) In the Yorkshire & the Humber the average farm size in 2019 was 93 hectares. This is larger than the English average of 87 hectares. Predominant farm types in the Yorkshire & the Humber region in 2019 were Grazing Livestock farms and Cereals farms which accounted for 32% and 30% of farmed area in the region. Although Pig farms accounted for a much smaller proportion of the farmed area, the region accounted for 37% of the English pig population. Land Labour Yorkshire & England Yorkshire & England the Humber the Humber Total farmed area (thousand 1,136 9,206 Total Labour(a) hectares People: 32,397 306,374 Average farm size (hectares) 93 87 Per farm(b) 2.7 2.9 % of farmed area that is: Regular workers Rented (for at least 1 year) 33% 33% People: 7,171 68,962 Arable area(a) 52% 52% Per farm(b) 0.6 0.6 Permanent pasture 35% 36% Casual workers (a) Includes arable crops, uncropped arable land and temporary People: 2,785 45,843 grass. -

An Introduction to Brigantia

Brigantia Yorkshire Moors Wolds,Coast and Dales Art and Craft Workers 1. What is Brigantia? Brigantia is an association, which brings together the very best of art and craft workers in the North York Moors, Wolds, Coast and Dales areas. 2. What is Brigantia's Objective? Being a non-profit making association, Brigantia has been formed to promote and improve the market potential of its members. The association carries a “label” of craftsmanship, which identifies products of originality and quality made within the area; the strength of that label provides professional and powerful marketing support to the craft and art worker. 3. What are the benefits to Brigantia members? the right to use a nationally recognised trademark of quality in the sale of their goods; retail opportunities through Brigantia exhibitions and participation in some shows, benefits from a presence on the World Wide Web; newsletters containing opportunities and other news; Other potential opportunities are always being identified and the association endeavours to develop initiatives, which have been identified by members including exhibitions, & short term retail outlets. We will always endeavour to meet the needs of our members. 4. Why Brigantia chose its name? Inspired by the countryside in which they operate the local art and craft workers chose Brigantia, the ancient name for part of North Yorkshire, as their sign of distinction, the Brigantes being renowned for their craft working skills. Brigantia’s logo is a Celtic knot, symbolising quality and craftsmanship. Brigantia was launched at Duncombe Park, Helmsley in October 1995. 5. Membership Only those art and craft workers who operate in the North York Moors and surrounding area will be eligible to join Brigantia. -

PDF (Volume 1)

Durham E-Theses Aspects of late iron age and Romano-British settlement in the lower Hull valley Didsbury, Michael Peter Townley How to cite: Didsbury, Michael Peter Townley (1990) Aspects of late iron age and Romano-British settlement in the lower Hull valley, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6477/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT The lower Hull valley is an extensive tract of estuarine alluvium between Kingston upon Hull and Beverley, North Humberside. The thesis examines the evidence for later Iron Age and Romano-British settlement in a landscape block of £. 330 km , incorporating the valley proper and the higher glacial deposits at its margins. The discussion utilises a comprehensive and critical gazetteer of some two hundred and twenty sites and findspots, and seven detailed site-studies present the results of the author's fieldwork or analysis of previously unpublished material assemblages.