Yangtze Patrol: American Naval Forces in China: a Selected, Partially-Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiral David G. Farragut

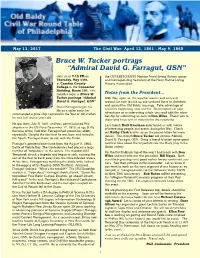

May 11, 2017 The Civil War: April 12, 1861 - May 9, 1865 Bruce W. Tucker portrays “Admiral David G. Farragut, USN” Join us at 7:15 PM on the USS LEHIGH/USS Monitor Naval Living History group Thursday, May 11th, and Corresponding Secretary of the Navy Marine Living at Camden County History Association. College in the Connector Building, Room 101. This month’s topic is Bruce W. Notes from the President... Tucker portrays “Admiral With May upon us, the weather warms and we travel David G. Farragut, USN” around; be sure to pick up our updated flyers to distribute David Farragut began his and spread the Old Baldy message. Take advantage of life as a sailor early; he activities happening near and far. Share reports of your commanded a prize ship captured in the War of 1812 when adventures or an interesting article you read with the mem- he was just twelve years old. bership by submitting an item to Don Wiles. Thank you to those who have sent in material for the newsletter. He was born July 5, 1801, and was commissioned Mid- Last month Herb Kaufman entertained us with stories shipman in the US Navy December 17, 1810, at age 9. By of interesting people and events during the War. Check the time of the Civil War, Farragut had proven his ability out Kathy Clark’s write up on the presentation for more repeatedly. Despite the fact that he was born and raised in details. This month Bruce Tucker will portray Admiral the South, Farragut chose to side with the Union. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Fighting Hunger As a Young Cavalryman in Vietnam, Bob 22 Nice Try Taliban Martin Saved a Baby in a Bombed-Out 26 Vietnam Vet Saves Baby Bunker

‘NICE TRY TALIBAN’ SEVERELY WOUNDED VET RETURNS TO AFGHANISTAN Fighting HungerON THE FRONT LINES ‘I CAN’T JUST LEAVE HER HERE’ A VFW member searches for a woman he saved 48 years ago in Vietnam REBUILDING MOTORCYCLES & VETS FOR THE MANY REASONS YOU SERVED, thank you. There are many reasons why you served, and our reason to serve is you. That’s why USAA is dedicated to helping support VFW members and their families. USAA means United Services Automobile Association and its affi liates. The VFW receives fi nancial support for this sponsorship. © 2018 USAA. 248368-0318 PHOTO BY TOM M. JOHNSON ‘NICE TRY TALIBAN’ SEVERELY WOUNDED VET RETURNS TO AFGHANISTAN Fighting HungerON THE FRONT LINES ‘I CAN’T JUST LEAVE HER HERE’ A VFW member searches for a woman he saved 48 years ago in Vietnam REBUILDING MOTORCYCLES & VETS AUGUST 2018 Vol. 105 No. 10 COVER PHOTO: Rich Synek, a member of VFW’s Department of New York, displays AFGHANISTAN VET RETURNS products available at his food pantry in After being blown up and losing parts of both legs in a 2011 IED Utica. Synek and his wife, Michele, created 22 the nonprofi t Feed Our Vets, providing explosion in Afghanistan, Justin Lane revisited the country earlier free food to veterans and their families. It this year. The trip allowed the former combat engineer to fulfi ll a goal includes a pantry in Watertown, a mobile he had carried with him for seven years. BY JIM SERVI unit in Syracuse and a gift card program that helps hungry vets around the country. -

Andrew Hull Foote, Gunboat Commodore

w..:l ~ w 0 r:c Qo (:.L..Q r:c 0 (Y) ~OlSSIJr;v, w -- t----:1 ~~ <.D ~ r '"' 0" t----:1 ~~ co ~ll(r~'Sa ~ r--1 w :::JO ...~ I ' -I~~ ~ ~0 <.D ~~if z E--t 0 y ~& ~ co oQ" t----:1 ~~ r--1 :t.z-~3NNO'l ............. t----:1 w..:l~ ~ o::z z0Q~ ~ CONNECTICUT CIVIL WAR CENTENNIAL COMMISSION • ALBERT D. PUTNAM, Chairman WILLIAM J. FINAN, Vice Chairman WILLIAM J. LoWRY, Secretary ALBERT D. PUTNAM (CHAJRMAN) .. ......................... Hartf01'd HAMILTON BAsso .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ...... .. Westport PRoF. HAROLD J. BINGHAM ................................... New Britain lHOMAs J. CALDWELL ............................................ Rocky Hill J. DoYLE DEWITT ............................................ West Hartford RoBERT EISENBERG .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Stratford WILLIAM J. FINAN ..................................................... W oodmont DANIEL I. FLETCHER . ........ ... ..... .. ... .... ....... .. ... Hartf01'd BENEDICT M. HoLDEN, JR. ................................ W est Hartford ALLAN KELLER . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Darien MRs. EsTHER B. LINDQUIST .................................. ......... Gltilford WILLIAM J. LoWRY .. .......................................... Wethersfield DR. WM. J. MAsSIE ............................................. New Haven WILLIAM E. MILLs, JR. ........................ ,....... ......... ........ Stamford EDwARD OLSEN .............................. .............. .. ..... Westbrook. -

Shipbuilding Industry 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Shipbuilding Industry Content

UKRINMASH SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY CONTENT 24 М15-V Marine Powerplant CONTENT М15-A Marine Powerplant 25 М35 Marine Powerplant М10/M16 Marine Powerplant 4 PROJECT 958 Amphibious Assault Hovercraft 26 UGT 3000R Gas-Turbine Engine KALKAN-МP Patrol Water-Jet Boat UGT 6000 Gas-Turbine Engine 5 GAYDUK-M Multipurpose Corvette 27 UGT 6000+ Gas-Turbine Engine GYURZA Armored River Gunboat UGT 15000 Gas-Turbine Engine 6 PROJECT 58130S Fast Patrol Boat 28 UGT 15000+ Gas-Turbine Engine CORAL Patrol Water-Jet Boat UGT 16000R Gas-Turbine Engine 7 BOBR Landing Craft/Military Transport 29 UGT 25000 Gas-Turbine Engine TRITON Landing Ship Tank 457KM Diesel Engine 8 BRIZ-40М Fast Patrol Boat 30 NAVAL AUTOMATED TACTICAL DATA SYSTEM BRIZ-40P Fast Coast Guard Boat MULTIBEAM ACTIVE ARRAY SURVEILLANCE RADAR STATION 9 PC655 Multipurpose Fast Corvette MUSSON Multipurpose Corvette 31 SENS-2 Optical Electronic System Of Gun Mount Fire Control 10 CARACAL Fast Attack Craft SAGA Optical Electronic System Of The Provision Corvette 58250 PROJECT Of Helicopter Take-Off, Homing And Ship Landing 11 GURZA-M Small Armored Boat 32 SARMAT Marine Optoelectronic Fire Control System Offshore Patrol Vessel DOZOR Of Small And Middle Artillery Caliber 12 KENTAVR Fast Assault Craft SONAR STATION MG – 361 (“CENTAUR”) PEARL-FAC Attack Craft-Missile 33 TRONKA-MK Hydroacoustic Station For Searching 13 NON-SELF-PROPELLED INTEGRATED SUPPORT VESSEL Of Saboteur Underwater Swimmers FOR COAST GUARD BOATS HYDROACOUSTIC STATION KONAN 750BR Fast Armored -

66-3392 KOGINOS, Emmanuel Theodore, 1933— the PANAY INCIDENT: PRELUDE to WAR. the American University, Ph.D„ 1966 History

66-3392 KOGINOS, Emmanuel Theodore, 1933— THE PANAY INCIDENT: PRELUDE TO WAR. The American University, Ph.D„ 1966 History, modern Please note: Author also indicates first name as Manny on the title page. University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by EMMANUEL THEODORE KOGINOS 1966 THE PANAY INCIDENT: PRELUDE TO WAR by y $anny)T^Koginos Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Signatures of Committee: f A Vk 0 Chairman: O* lOctMr**- /~) y\ 7 ■ * Graduate Dean: Date: 2 7./9CS- Thewf^Mna?nnUnnVerSity AMERICAN UNIVERSITY Washington, D. C. LIBRARY ffOV 8 1965 WASHINGTON. D.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE i CHAPTER Page I. Diplomatic Background .......... 1 II. The Crisis ............. hi III. The Settlement ........ 101 IV. The Ludlow Referendum............ 150 V. Naval Expansion ............. 190 VI. Conclusion........................... 2k2 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................... ....250 APPENDICES ........................................ 267 PREFACE The Panav incident in retrospect was the most dramatic single event in Japanese-American relations during the 1930's. i-.-. The attack upon the American gunboat in December, 1937 by Japanese forces contributed greatly to the general deterior ation and eventual breakdown in American-Japanese diplomatic relations. Though the immediate impact of the incident did not result in any radical departure from America's isola tionist position, it did modify American opinion in respect to foreign and domestic affairs. Indeed, pacifist influ ence was to reach its highest crest during the Panav epi sode. At the same time, the crisis vividly dramatized America's unwillingness to pursue a more positive policy in the Far East. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs British ships and West China, 1875-1941: With special reference to the Upper Yangtze. Thesis How to cite: Blue, Archibald Duncan (1978). British ships and West China, 1875-1941: With special reference to the Upper Yangtze. The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 1977 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000f7cc Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk BRITISH SHIPS AND WEST CHINA, l8?3 ~ 19^1 With special reference to the Upper Yangtze A DISSERTATION Submitted for the Degree of Bachelor of Philosophy to the Open University by Archibald Duncan Blue March 1978 (J ProQ uest Number: 27919402 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. in the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 27919402 Published by ProQuest LLC (2020). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. Ail Rights Reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

VMI Men Who Wore Yankee Blue, 1861-1865 by Edward A

VMI Men Who Wore Yankee Blue, 1861-1865 by Edward A. Miller, ]r. '50A The contributions of Virginia Military Institute alumni in Confed dent. His class standing after a year-and-a-half at the Institute was erate service during the Civil War are well known. Over 92 percent a respectable eighteenth of twenty-five. Sharp, however, resigned of the almost two thousand who wore the cadet uniform also wore from the corps in June 1841, but the Institute's records do not Confederate gray. What is not commonly remembered is that show the reason. He married in early November 1842, and he and thirteen alumni served in the Union army and navy-and two his wife, Sarah Elizabeth (Rebeck), left Jonesville for Missouri in others, loyal to the Union, died in Confederate hands. Why these the following year. They settled at Danville, Montgomery County, men did not follow the overwhelming majority of their cadet where Sharp read for the law and set up his practice. He was comrades and classmates who chose to support the Common possibly postmaster in Danville, where he was considered an wealth and the South is not difficult to explain. Several of them important citizen. An active mason, he was the Danville delegate lived in the remote counties west of the Alleghenies where to the grand lodge in St. Louis. In 1859-1860 he represented his citizens had long felt estranged from the rest of the state. Citizens area of the state in the Missouri Senate. Sharp's political, frater of the west sought to dismember Virginia and establish their own nal, and professional prominence as well as his VMI military mountain state. -

Battles of Mobile Bay, Petersburg, Memorialized on Civil War Forever Stamps Today Fourth of Five-Year Civil War Sesquicentennial Stamps Series Continues

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts July 30, 2014 VA: Freda Sauter 401-431-5401 [email protected] AL: Debbie Fetterly 954-298-1687 [email protected] National: Mark Saunders 202-268-6524 [email protected] usps.com/news To obtain high-resolution stamp images for media use, please email [email protected]. For broadcast quality video and audio, photo stills and other media resources, visit the USPS Newsroom. Battles of Mobile Bay, Petersburg, Memorialized on Civil War Forever Stamps Today Fourth of Five-Year Civil War Sesquicentennial Stamps Series Continues MOBILE, AL — Two of the most important events of the Civil War — the Battle of Mobile Bay (AL) and the siege at Petersburg, VA — were memorialized on Forever stamps today at the sites where these conflicts took place. One stamp depicts Admiral David G. Farragut’s fleet at the Battle of Mobile Bay (AL) on Aug. 5, 1864. The other stamp depicts the 22nd U.S. Colored Troops engaged in the June 15-18, 1864, assault on Petersburg, VA, at the beginning of the Petersburg Campaign. “The Civil War was one of the most intense chapters in our history, claiming the lives of more than 620,000 people,” said Postmaster General Patrick Donahoe in dedicating the Mobile Bay stamp. “Today, through events and programs held around the country, we’re helping citizens consider how their lives — and their own American experience — have been shaped by this period of history.” In Petersburg, Chief U.S. Postal Service Inspector Guy Cottrell dedicated the stamps just yards from the location of an underground explosion — that took place150 years ago today — which created a huge depression in the earth and led to the battle being named “Battle of the Crater.” Confederates — enraged by the sight of black soldiers — killed many soldiers trapped in the crater attempting to surrender. -

THE JERSEYMAN 5 Years - Nr

1st Quarter 2007 "Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if again sounded, to provide firepower for freedom…” THE JERSEYMAN 5 Years - Nr. 53 USS NEW JERSEY Primerman - Turret Two... “I was a primerman left gun, and for a short time, in right gun of turret two on the New Jersey. In fact there was a story written by Stars and Stripes on the gun room I worked in about July or August 1986. But to your questions, yes we wore a cartridge belt, the belt was stored in a locker in the turret, and the gun captain filled the belts. After the gun was loaded with rounds, six bags of powder (large bags were 110 lbs. each) and lead foil, the gun elevated down to the platform in the pit where loaded, and the primer was about the same size as a 30-30 brass cartridge. After I loaded the primer I would give the gun captain a "Thumbs up," the gun captain then pushed a button to let them know that the gun was loaded and ready to fire. After three tones sounded, the gun fired, the gun captain opened the breech and the empty primer fell Primer cartridge courtesy of Volunteer into the pit. Our crew could have a gun ready to fire Turret Captain Marty Waltemyer about every 27 seconds. All communicating was done by hand instructions only, and that was due to the noise in the turret. The last year I was in the turrets I was also a powder hoist operator...” Shane Broughten, former BM2 Skyberg, Minnesota USS NEW JERSEY 1984-1987 2nd Div. -

Gunboat Economics?

Andreas Exenberger, Dr. Research Area “Economic and Social History” Faculty of Economics and Statistics, Leopold-Franzens-University Innsbruck Universitaetsstrasse 15, A-6020 Innsbruck Tel.: (+43)-(0)512-507-7409 E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.uibk.ac.at/economics/exenberger Paper for AHE 08 (London, July 14-16, 2006) (Version of June 1, 2006; rough draft, no citation without explicit permission) Gunboat Economics? An Essay about some of the Relationships between Wealth and Violence Introduction By working on the relevance of violence in economics (from an historical perspective) I discovered something seeming rather strange at first site: although there are a lot of historical examples that the performance (and appearance) of “gunboats” (not necessarily in the literal sense) directly influenced economic relations, there is no conceptual approach about that interrelation neither in economics nor in history. And while the term “gunboat diplomacy” is cited extensively in political and historical (and sometimes even in economical) contexts und even more, is commonly understood, there is no such thing as “gunboat economics” at all. To be correct, this is not completely true. In 1985 Jeffrey Garten published an article in Foreign Affairs even entitled “Gunboat Economics”. In the text however, he did not mention the term again and confuses it throughout the article, which is mainly a critique of Reaganomics and the unilateral (and economically protectionist) foreign policy of the administration Reagan I (1981-84), with gunboat diplomacy. Interestingly enough, during the last twenty years U.S. problem-solving did not change very much and both Bushes as well as Clinton continued and even intensified a foreign policy resting on means that can be summarized as “gunboats” (as I said, not necessarily in the literal sense, because the “gunboats” of our times are not battleships, but long-distance missiles, intervention forces and diplomatic pressure). -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph.