10 Writing in Early Mesoamerica Before It Can Be Clearly Defined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The PARI Journal Vol. XIV, No. 2

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XIV, No. 2, Fall 2013 Mesoamerican Lexical Calques in Ancient Maya Writing and Imagery In This Issue: CHRISTOPHE HELMKE University of Copenhagen Mesoamerican Lexical Calques Introduction ancient cultural interactions which might otherwise go undetected. in Ancient Maya The process of calquing is a fascinating What follows is a preliminary treat- Writing and Imagery aspect of linguistics since it attests to ment of a small sample of Mesoamerican contacts between differing languages by lexical calques as attested in the glyphic and manifests itself in a variety of guises. Christophe Helmke corpus of the ancient Maya. The present Calquing involves loaning or transferring PAGES 1-15 treatment is not intended to be exhaus- items of vocabulary and even phonetic tive; instead it provides an insight into • and syntactic traits from one language 1 the types, antiquity, and longevity of to another. Here I would like to explore The Further Mesoamerican calques in the hopes that lexical calques, which is to say the loaning Adventures of Merle this foray may stimulate additional and of vocabulary items, not as loanwords, (continued) more in-depth treatment in the future. but by means of translating their mean- by ing from one language to another. In this Merle Greene sense calques can be thought of as “loan Calques in Mesoamerica Robertson translations,” in which only the semantic Lexical calques have occupied a privileged PAGES 16-20 dimension is borrowed. Calques, unlike place in the definition of Mesoamerica as a loanwords, are not liable to direct phono- linguistic area (Campbell et al. -

A Sign Catalog of the Isthmian Script

Glyph Dwellers Report 51 February 2017 A Sign Catalog of the Isthmian Script Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis It has been 110 years since the publication of the inscription on a six-inch jade figurine, the Tuxtla Statuette, found in a field in San Andrés, Tuxtla, Veracruz (Holmes 1907; Holmes 1916), and 30 years since the six-foot La Mojarra Stela was pulled out of the Acula River in the municipio of Alvarado, Veracruz (Winfield Capitaine 1988). Since that time the script has seen a somewhat overstated claim of decipherment (Justeson and Kaufman 1993), and the discovery of an extended text on the back of a feldspar mask resulting in a challenge to that decipherment (Houston and Coe 2003). E. Logan Wagner's photographs of the La Mojarra inscription were shown at the Maya Meetings at the University of Texas at Austin in March of 1987 to an amazed audience—this author included. Immediately upon the publication of the monument by George Stuart and Winfield Capitaine (1988), Laura Stark and I began analysis of the two texts and began to put together a sign list. One of the first tasks necessary for decipherment is to establish the list of signs, also called graphemes, which represent the minimal meaningful graphic elements of the script. This involves determining the number of occurrences of a grapheme, identifying the variants of a single sign, and distinguishing between compound graphemes (signs composed of two or more elements) and compound signs (sign groups composed of two or more graphemes). -

The Moche Lima Beans Recording System, Revisited

THE MOCHE LIMA BEANS RECORDING SYSTEM, REVISITED Tomi S. Melka Abstract: One matter that has raised sufficient uncertainties among scholars in the study of the Old Moche culture is a system that comprises patterned Lima beans. The marked beans, plus various associated effigies, appear painted by and large with a mixture of realism and symbolism on the surface of ceramic bottles and jugs, with many of them showing an unparalleled artistry in the great area of the South American subcontinent. A range of accounts has been offered as to what the real meaning of these items is: starting from a recrea- tional and/or a gambling game, to a divination scheme, to amulets, to an appli- cation for determining the length and order of funerary rites, to a device close to an accountancy and data storage medium, ending up with an ‘ideographic’, or even a ‘pre-alphabetic’ system. The investigation brings together structural, iconographic and cultural as- pects, and indicates that we might be dealing with an original form of mnemo- technology, contrived to solve the problems of medium and long-distance com- munication among the once thriving Moche principalities. Likewise, by review- ing the literature, by searching for new material, and exploring the structure and combinatory properties of the marked Lima beans, as well as by placing emphasis on joint scholarly efforts, may enhance the studies. Key words: ceramic vessels, communicative system, data storage and trans- mission, fine-line drawings, iconography, ‘messengers’, painted/incised Lima beans, patterns, pre-Inca Moche culture, ‘ritual runners’, tokens “Como resultado de la falta de testimonios claros, todas las explicaciones sobre este asunto parecen in- útiles; divierten a la curiosidad sin satisfacer a la razón.” [Due to a lack of clear evidence, all explana- tions on this issue would seem useless; they enter- tain the curiosity without satisfying the reason] von Hagen (1966: 157). -

Ladder of Cultural Evolution Is Reflected in the Terms "Formative" and "Preclassic" Generally Applied Today to These Remains

II. EARLY AND MIDDLE PRECLASSIC CULTURE IN THE BASIN OF MEXICO* Paul Tolstoy and Louise I. Paradis Between the 1st century of our era and the 16th, the Basin of Mexico saw the rise, one after the other, of what were probably the two largest cities of pre-Columbian America: Teotihuacan and Mexico-Tenochititlan. The preclassic settlements that precede these giants in the Basin are therefore of more than passing interest. Their study contributes inevitably to the perspective in which we view these two later centers of Mesoamerican civili- zation. Much of our present understanding of Preclassic cultures in the Basin of Mexico comes to us from the work of George C. Vaillant at the sites of Zacatenco (1), Ticoman (2), and El Arbolillo (X). In the late 1920's and early 1930's, Vaillant brought to light the refuse deposits of these three small farming communities,, situated on the lower slopes of the hills of Guadalupe, on what was once the north shore of a bay of Lake Texcoco, and what is today the rim of a flat plain covered by Mexico City. Vaillant's sites, the first of their kind to be thoroughly tested and reported, represent the stage preceding the appearance of native civili- zations in the Central Highlands of Mesoamerica. This position on the ladder of cultural evolution is reflected in the terms "Formative" and "Preclassic" generally applied today to these remains. Vaillant, not with- out wisdom, referred to them as the "Middle cultures" (4), recognizing in this way that they obviously did not represent the beginnings of settled life, farming, or most of the other practices and crafts known to these villagers. -

The Gentics of Civilization: an Empirical Classification of Civilizations Based on Writing Systems

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 49 Number 49 Fall 2003 Article 3 10-1-2003 The Gentics of Civilization: An Empirical Classification of Civilizations Based on Writing Systems Bosworth, Andrew Bosworth Universidad Jose Vasconcelos, Oaxaca, Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Bosworth, Bosworth, Andrew (2003) "The Gentics of Civilization: An Empirical Classification of Civilizations Based on Writing Systems," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 49 : No. 49 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol49/iss49/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Bosworth: The Gentics of Civilization: An Empirical Classification of Civil 9 THE GENETICS OF CIVILIZATION: AN EMPIRICAL CLASSIFICATION OF CIVILIZATIONS BASED ON WRITING SYSTEMS ANDREW BOSWORTH UNIVERSIDAD JOSE VASCONCELOS OAXACA, MEXICO Part I: Cultural DNA Introduction Writing is the DNA of civilization. Writing permits for the organi- zation of large populations, professional armies, and the passing of complex information across generations. Just as DNA transmits biolog- ical memory, so does writing transmit cultural memory. DNA and writ- ing project information into the future and contain, in their physical structure, imprinted knowledge. -

Rao Et Al., 2009A; Rao, 2010) Or Lee and Colleagues (Lee Et Al., 2010A) Works

Corpora and Statistical Analysis of Non-Linguistic Symbol Systems Richard Sproat January 21, 2013 Abstract We report on the creation and analysis of a set of corpora of non-linguistic symbol systems. The resource, the first of its kind, consists of data from seven systems, both ancient and modern, with two further systems under development, and several others planned. The systems represent a range of types, including heraldic systems, formal systems, and systems that are mostly or purely decorative. We also compare these systems statistically with a large set of linguistic systems, which also range over both time and type. We show that none of the measures proposed in published work by Rao and colleagues (Rao et al., 2009a; Rao, 2010) or Lee and colleagues (Lee et al., 2010a) works. In particular, Rao’s entropic measures are evidently useless when one considers a wider range of examples of real non-linguistic symbol systems. And Lee’s measures, with the cutoff values they propose, misclassify nearly all of our non-linguistic systems. However, we also show that one of Lee’s measures, with different cutoff values, as well as another measure we develop here, do seem useful. We further demonstrate that they are useful largely because they are both highly correlated with a rather trivial feature: mean text length. ⃝c 2012–2013, Richard Sproat 1 1 Introduction Humans have been using symbols for many millenia to represent many different kinds of information. In some cases a single symbol represents a single concept, and is not part of any larger symbol system: an example is the red, blue and white helical symbol for a barber shop. -

An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala

Glyph Dwellers Report 65 October 2020 An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis A dichotomy between Olmec and Maya art styles on the stone monuments of the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj was proposed a number of years ago (e.g., Graham 1979). Researchers now recognize a more nuanced division between Olmec and developing Isthmian/Maya1 traditions (Graham 1989; Mora- Marín 2005; Popenoe de Hatch, Schieber de Lavarreda, and Orrego Corzo 2011; Schieber de Lavarreda 2020; Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010). John Graham proposed the term "Early Isthmian" rather than "Olmec" to describe examples of the Preclassic texts of southern Mesoamerica (Graham 1971:134). In this paper the term "Isthmian" is restricted to the script found on the Tuxtla Statuette (Holmes 1907), La Mojarra Stela 1 (Winfield Capitaine 1988), and related texts. Internal evidence within Isthmian texts themselves, specifically variation in both sign use and sign form, suggests that the origin of the Isthmian script dates significantly earlier than the long count dates on the two earliest known examples: La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette (Macri 2017a). Two items of stratigraphic evidence from Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas show a presence of the script at that site, beyond the Gulf region, pushing the origin of the script even further back in time (Macri 2017b). This report considers several texts from the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj, specifically two monuments, that have long count dates only slightly earlier those on La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette, to suggest an even broader geographic and temporal range for the Isthmian script tradition. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

The Cult of the Book. What Precolumbian Writing Contributes to Philology

10.3726/78000_29 The Cult of the Book. What Precolumbian Writing Contributes to Philology Markus Eberl Vanderbilt University, Nashville Abstract Precolumbian people developed writing independently from the Old World. In Mesoamerica, writing existed among the Olmecs, the Zapotecs, the Maya, the Mixtecs, the Aztecs, on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and at Teotihuacan. In South America, the knotted strings or khipus were used. Since their decipherment is still ongoing, Precolumbian writing systems have often been studied only from an epigraphic perspective and in isolation. I argue that they hold considerable interest for philology because they complement the latter’s focus on Western writing. I outline the eight best-known Precolumbian writing systems and de- scribe their diversity in form, style, and content. These writing systems conceptualize writing and written communication in different ways and contribute new perspectives to the study of ancient texts and languages. Keywords Precolumbian writing, decipherment, defining writing, authoritative discourses, canon Introduction Written historical sources form the basis for philology. Traditionally these come from the Western world, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Few classically trained scholars are aware of the ancient writing systems in the Americas and the recent advances in deciphering them. In Mesoamerica – the area of south-central Mexico and western Central America – various societies had writing (Figure 1). This included the Olmecs, the Zapotecs, the people of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Maya, Teotihuacan, Mix- tecs, and the Aztecs. In South America, the Inka used knotted strings or khipus (Figure 2). At least eight writing systems are attested. They differ in language, formal structure, and content. -

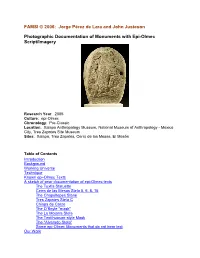

Photographic Documentation of Monuments with Epi-Olmec Script/Imagery

FAMSI © 2006: Jorge Pérez de Lara and John Justeson Photographic Documentation of Monuments with Epi-Olmec Script/Imagery Research Year : 2005 Culture : epi-Olmec Chronology : Pre-Classic Location : Xalapa Anthropology Museum, National Museum of Anthropology - Mexico City, Tres Zapotes Site Museum Sites : Xalapa, Tres Zapotes, Cerro de las Mesas, El Mesón Table of Contents Introduction Background Working Universe Technique Known epi-Olmec Texts A sketch of prior documentation of epi-Olmec texts The Tuxtla Statuette Cerro de las Mesas Stela 5, 6, 8, 15 The Chapultepec Stone Tres Zapotes Stela C Chiapa de Corzo The O’Boyle "mask" The La Mojarra Stela The Teotihuacan-style Mask The "Alvarado Stela" Some epi-Olmec Monuments that do not bear text Our Work The La Mojarra Stela Tres Zapotes Stela C Monuments of or relating to Cerro de las Mesas The Alvarado Stela Epi-Olmec monuments from El Mesón Acknowledgements List of Photographs Sources Cited Introduction This photographic documentation project provides photographic documentation of monuments in Mexican museums belonging to the so-called epi-Olmec tradition. The main purpose of this report is to disseminate a set of photographs that constitute part of the primary documentation of epi-Olmec monuments, with particular emphasis on those bearing epi-Olmec texts, and of a few monuments from a tradition that we suspect replaced it at Cerro de las Mesas. It does not include objects that are well-published elsewhere, nor does it include two objects to which we have been unable to gain access to. Its first aim is to marry a trustworthy photographic record and the web presence of FAMSI for the purpose of making widely available a large percentage of the corpus of monuments belonging to this cultural tradition. -

Lorenza López Mestas Camberos

FAMSI © 2008: Lorenza López Mestas Camberos Green Stones in Central Jalisco Translation of the Spanish by Eduardo Williams Research Year: 2004 Culture: Teuchitlán Tradition and El Grillo complex Chronology: Late Preclassic to Late Classic Location: Magdalena and Tala municipalities, Jalisco, Mexico Sites: Huitzilapa and La Higuerita Table of Contents Early use of green stones in western Mesoamerica The site of Huitzilapa during the Late Formative Green stones in Huitzilapa The site of La Higuerita during the Late Classic Green stones in La Higuerita Conclusions List of Figures Sources Cited Submitted 09/01/2006 by: Mtra. Lorenza López Mestas Camberos Centro INAH Jalisco [email protected] [email protected] Early use of green stones in western Mesoamerica Objects made out of a wide variety of green stones were greatly valued by Mesoamerican cultures since early times. The oldest dates for the use of these kinds of materials pertain to the Early Formative, in the Barra complex of the Pacific coast of Chiapas (Garber et al. 1993: 211). A little later their presence was more widespread, above all in funerary contexts of the San José phase of the Oaxaca Valley (1150-850 B.C.), as well as in Tlatilco, in the Basin of Mexico (ca. 900 B.C.) around the latter date their use seems to have been more generalized, including such sites as La Venta, on the coastal Gulf zone and Copán, Honduras (Ibid.: 212). In spite of the importance of these materials, little is known about the existence and use patterns of green stones in western Mesoamerica. This is due in part to the few systematic excavations carried out in this region, as well as the little interest shown by archaeologists on the study of this kind of materials. -

Selected Works Selected Works Works Selected

Celebrating Twenty-five Years in the Snite Museum of Art: 1980–2005 SELECTED WORKS SELECTED WORKS S Snite Museum of Art nite University of Notre Dame M useum of Art SELECTED WORKS SELECTED WORKS Celebrating Twenty-five Years in the Snite Museum of Art: 1980–2005 S nite M useum of Art Snite Museum of Art University of Notre Dame SELECTED WORKS Snite Museum of Art University of Notre Dame Published in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Snite Museum of Art building. Dedicated to Rev. Anthony J. Lauck, C.S.C., and Dean A. Porter Second Edition Copyright © 2005 University of Notre Dame ISBN 978-0-9753984-1-8 CONTENTS 5 Foreword 8 Benefactors 11 Authors 12 Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art 68 Native North American Art 86 African Art 100 Western Arts 264 Photography FOREWORD From its earliest years, the University of Notre Dame has understood the importance of the visual arts to the academy. In 1874 Notre Dame’s founder, Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., brought Vatican artist Luigi Gregori to campus. For the next seventeen years, Gregori beautified the school’s interiors––painting scenes on the interior of the Golden Dome and the Columbus murals within the Main Building, as well as creating murals and the Stations of the Cross for the Basilica of the Sacred Heart. In 1875 the Bishops Gallery and the Museum of Indian Antiquities opened in the Main Building. The Bishops Gallery featured sixty portraits of bishops painted by Gregori. In 1899 Rev. Edward W. J.