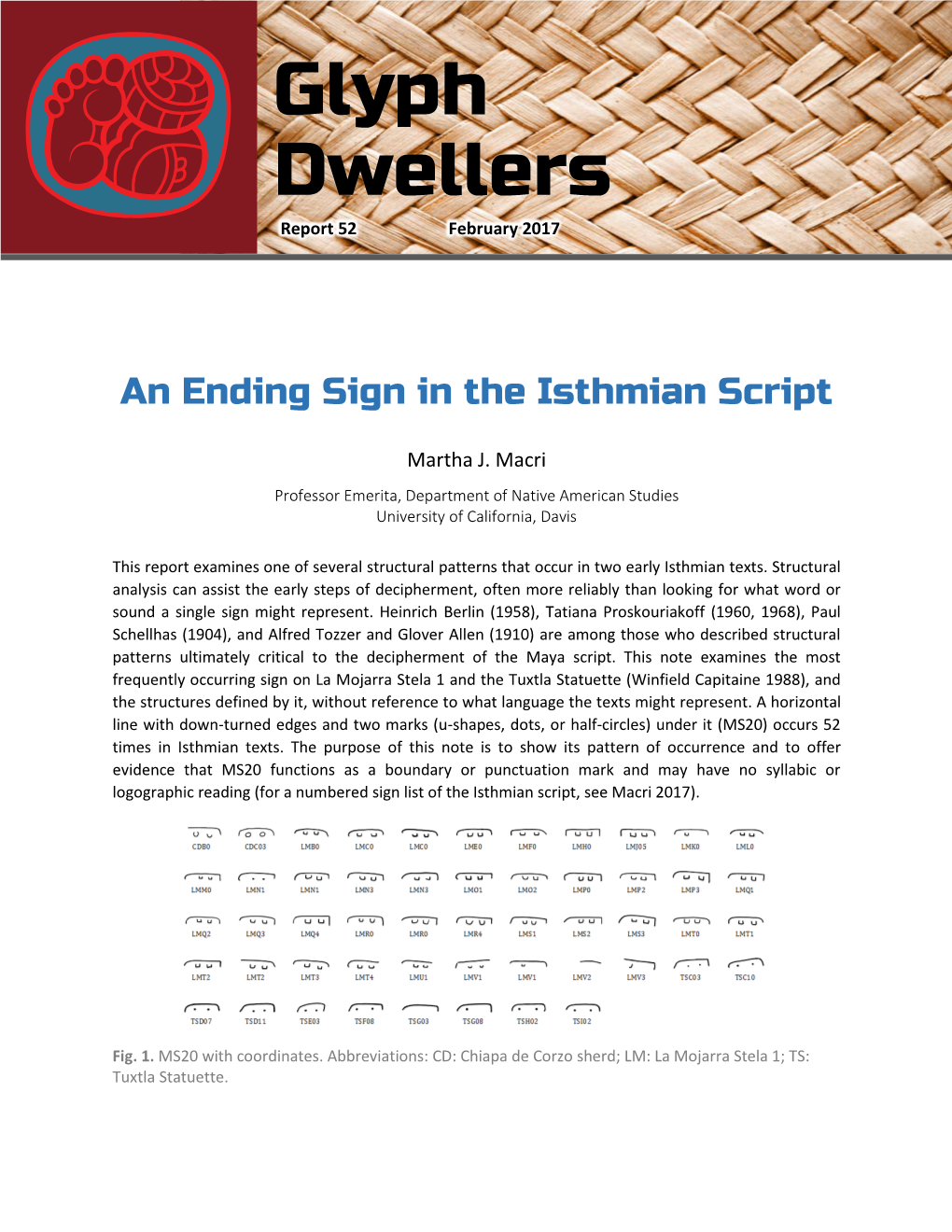

Report 52 February 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sign Catalog of the Isthmian Script

Glyph Dwellers Report 51 February 2017 A Sign Catalog of the Isthmian Script Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis It has been 110 years since the publication of the inscription on a six-inch jade figurine, the Tuxtla Statuette, found in a field in San Andrés, Tuxtla, Veracruz (Holmes 1907; Holmes 1916), and 30 years since the six-foot La Mojarra Stela was pulled out of the Acula River in the municipio of Alvarado, Veracruz (Winfield Capitaine 1988). Since that time the script has seen a somewhat overstated claim of decipherment (Justeson and Kaufman 1993), and the discovery of an extended text on the back of a feldspar mask resulting in a challenge to that decipherment (Houston and Coe 2003). E. Logan Wagner's photographs of the La Mojarra inscription were shown at the Maya Meetings at the University of Texas at Austin in March of 1987 to an amazed audience—this author included. Immediately upon the publication of the monument by George Stuart and Winfield Capitaine (1988), Laura Stark and I began analysis of the two texts and began to put together a sign list. One of the first tasks necessary for decipherment is to establish the list of signs, also called graphemes, which represent the minimal meaningful graphic elements of the script. This involves determining the number of occurrences of a grapheme, identifying the variants of a single sign, and distinguishing between compound graphemes (signs composed of two or more elements) and compound signs (sign groups composed of two or more graphemes). -

An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala

Glyph Dwellers Report 65 October 2020 An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis A dichotomy between Olmec and Maya art styles on the stone monuments of the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj was proposed a number of years ago (e.g., Graham 1979). Researchers now recognize a more nuanced division between Olmec and developing Isthmian/Maya1 traditions (Graham 1989; Mora- Marín 2005; Popenoe de Hatch, Schieber de Lavarreda, and Orrego Corzo 2011; Schieber de Lavarreda 2020; Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010). John Graham proposed the term "Early Isthmian" rather than "Olmec" to describe examples of the Preclassic texts of southern Mesoamerica (Graham 1971:134). In this paper the term "Isthmian" is restricted to the script found on the Tuxtla Statuette (Holmes 1907), La Mojarra Stela 1 (Winfield Capitaine 1988), and related texts. Internal evidence within Isthmian texts themselves, specifically variation in both sign use and sign form, suggests that the origin of the Isthmian script dates significantly earlier than the long count dates on the two earliest known examples: La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette (Macri 2017a). Two items of stratigraphic evidence from Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas show a presence of the script at that site, beyond the Gulf region, pushing the origin of the script even further back in time (Macri 2017b). This report considers several texts from the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj, specifically two monuments, that have long count dates only slightly earlier those on La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette, to suggest an even broader geographic and temporal range for the Isthmian script tradition. -

Photographic Documentation of Monuments with Epi-Olmec Script/Imagery

FAMSI © 2006: Jorge Pérez de Lara and John Justeson Photographic Documentation of Monuments with Epi-Olmec Script/Imagery Research Year : 2005 Culture : epi-Olmec Chronology : Pre-Classic Location : Xalapa Anthropology Museum, National Museum of Anthropology - Mexico City, Tres Zapotes Site Museum Sites : Xalapa, Tres Zapotes, Cerro de las Mesas, El Mesón Table of Contents Introduction Background Working Universe Technique Known epi-Olmec Texts A sketch of prior documentation of epi-Olmec texts The Tuxtla Statuette Cerro de las Mesas Stela 5, 6, 8, 15 The Chapultepec Stone Tres Zapotes Stela C Chiapa de Corzo The O’Boyle "mask" The La Mojarra Stela The Teotihuacan-style Mask The "Alvarado Stela" Some epi-Olmec Monuments that do not bear text Our Work The La Mojarra Stela Tres Zapotes Stela C Monuments of or relating to Cerro de las Mesas The Alvarado Stela Epi-Olmec monuments from El Mesón Acknowledgements List of Photographs Sources Cited Introduction This photographic documentation project provides photographic documentation of monuments in Mexican museums belonging to the so-called epi-Olmec tradition. The main purpose of this report is to disseminate a set of photographs that constitute part of the primary documentation of epi-Olmec monuments, with particular emphasis on those bearing epi-Olmec texts, and of a few monuments from a tradition that we suspect replaced it at Cerro de las Mesas. It does not include objects that are well-published elsewhere, nor does it include two objects to which we have been unable to gain access to. Its first aim is to marry a trustworthy photographic record and the web presence of FAMSI for the purpose of making widely available a large percentage of the corpus of monuments belonging to this cultural tradition. -

Desde La Matriz De Olman: the Birth of Writing in Formative Era Mesoamerica

Desde la matriz de Olman: The Birth of Writing in Formative Era Mesoamerica by Stephanie Michelle Strauss B.A. in Anthropology & Latin American Studies, May 2011, Yale University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 19, 2013 Thesis directed by Jeffrey P. Blomster Associate Professor of Anthropology © Copyright 2013 by Stephanie Michelle Strauss All rights reserved ii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this work to Stephen, for love, support, and never losing hope; to Debbie and Dale, for 23 years of encouragement and brave draft reading; to Scott, Aiden, Gregg, Laura, and Nathan, for providing love and levity; and to Dean, for keeping me company along the way. iii Acknowledgements The author wishes to acknowledge and sincerely thank Dr. Jeffrey Blomster for two years of guidance, encouragement, instruction, and support. I have become a better scholar, writer, and thinker under his excellent tutelage, and owe him a debt of gratitude. I would further like to thank Dr. Catherine Allen and Dr. Alexander Dent, both of who have deepened and enriched my theoretical work, and Dr. Linda Brown for her enthusiasm and suggestions. Lastly, I would like to thank Dr. Mary Miller for inspiring me to both begin and formally pursue this journey into Mesoamerican archaeology and epigraphy. iv Table of Contents Dedication..........................................................................................................................iii -

10 Writing in Early Mesoamerica Before It Can Be Clearly Defined

Writing in early Mesoamerica 275 time and space; a script with weaker boundaries will need closer scrutiny 10 Writing in early Mesoamerica before it can be clearly defined. One way of understanding such boundaries is in terms of "open" and STEPHEN D. HOUSTON "closed" writing systems (Houston 1994b). Eric Wolf first applied these labels in an entirely different context, to certain kinds of peasant societies (1955:462). "Open" implied a near-constant state of interaction with other societies, "closed" quite the opposite, having the connotation of a marked From about 500 years before Christ until the beginning of the Common state of isolation. As with any social typology, the terms do not correspond era, the peoples of Mesoamerica innovated, used, and developed a series precisely to any one society, nor are they altogether successful in charac of graphic systems that encoded language: in short, they created "writing" terizing the actual history of peasant communities (Monaghan 1995:61-62; where none existed before, almost certainly in isolation from Old World Wolf 1986:327). They do, however, emphasize an important point, that some inputs. That such systems were writing by any definition of the word (cf. properties of societies - or writing systems - transcend or supersede local Damerow 1999b:4-5; Gelb 1963:58) is now beyond dispute, especially in conditions while others accentuate them. The irony is that terms which the case of Maya script (Coe 1999). This chapter reviews how these develop fail to work for Wolf's peasants may apply persuasively -

The Peten and the Maya Lowlands the Mirador Region San Bartolo from Preclassic to Classic in the Maya Lowlands

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: Breaking the Maya Code Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs Angkor and the Khmer Civilization India: A Short History The Incas The Aztecs See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com CONTENTS Preface Chronological table 1 INTRODUCTION The setting Natural resources Areas Periods Peoples and languages Climate change and its cultural impact 2 THE EARLIEST MAYA Early hunters Archaic collectors and cultivators Early Preclassic villages The Middle Preclassic expansion Preclassic Kaminaljuyu The Maya lowlands 3 THE RISE OF MAYA CIVILIZATION The birth of the calendar Izapa and the Pacific Coast The Hero Twins and the Creation of the World (box) Kaminaljuyu and the Maya highlands The Peten and the Maya lowlands The Mirador region San Bartolo From Preclassic to Classic in the Maya lowlands 4 CLASSIC SPLENDOR: THE EARLY PERIOD Defining the Early Classic Teotihuacan: military giant The Esperanza culture Cerén: a New World Pompeii? Tzakol culture in the Central Area Copan in the Early Classic The Northern Area 5 CLASSIC SPLENDOR: THE LATE PERIOD Classic sites in the Central Area Copan and Quirigua Tikal Calakmul Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and Bonampak The Petexbatun Palenque Comalcalco and Tonina Classic sites in the Northern Area: Río Bec, Chenes, and Coba Art of the Late Classic 6 THE TERMINAL CLASSIC The Great Collapse Ceibal and the Putun Maya Puuc sites in the Northern Area The Terminal Classic at Chichen Itza Ek’ Balam The Cotzumalhuapa problem The end of -

University of Nevada, Reno Writing of the Americas a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degre

University of Nevada, Reno Writing of the Americas A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Jaycob A. Nolte Dr. Ian Clayton/Thesis Advisor Dr. Valerie Fridland/Thesis Co-Advisor May, 2021 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Jaycob Nolte entitled Writing of the Americas be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Dr. Ian Clayton Advisor Dr. Valerie Fridland Co-advisor Dr. Ignacio Montoya Committee Member Dr. Jenanne Ferguson Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean Graduate School May, 2021 i Abstract This paper aims to highlight the different forms of writing within the Americas, establish connections between the systems, and discuss the impact of European colonization. Writing systems within the American Continents contain a vast array of different indigenous systems that first started around 1000-900 BCE and spread throughout Mesoamerica into varying communities innovated to make their writing systems. The writing systems discussed are Olmec, Zapotec, Maya, Epi-Olmec, Teotihuacan, Aztec, Mixtec, Khipus, Cree, Cherokee, and Inuktitut writing systems. Primary sources of each system, secondary sources that discuss and synthesize these primary sources, policies, laws, and other cultural materials discussed within these indigenous communities are used throughout the paper to further the discussion. The impact of colonization on the writing systems of the Americas creates a division between pre-and post-contact systems that show the extent of colonial powers. This paper also discusses the writing systems that are still in use and their community's development of revitalization tools and resources. -

Isthmian Script at Chiapa De Corzo

Glyph Dwellers Report 56 July 2017 Isthmian Script at Chiapa de Corzo Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis The archaeological site of Chiapa de Corzo in Chiapas, Mexico, has a history that spans from the early Formative period, perhaps as early as 1150 BCE, to about 600 CE, well into the Classic period (Bachand and Lowe 2011). Situated in the Grijalva River valley, it was, in addition to being a major ceremonial center, a crossroads between the Gulf Coast region and the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala. Its affinity with the Olmec of La Venta can be seen from the similarity in placement of a number of architectural features, as well as from Olmec style jade celts, stone carvings, and figurines (Bachand and Lowe 2011). The site is unique in providing archaeological contexts for three artifacts from Middle and Late Preclassic periods that relate directly to the Isthmian script: an inscribed potsherd, a stela with a cycle seven long count date with a day name and number, and a tortoise shell pendant depicting an Olmec style carving of a person with a distinctive Isthmian-style ear ornament. All three of these items, including the stela fragment, are small enough to be considered portable objects—that is, they could easily be moved from one location to another. The incised sherd seems to represent a local manufacture; Stela 2 is unique among stela fragments in its light color and smooth finish; and the pendant of course, could easily have been manufactured elsewhere. Nevertheless, the information they offer about the Isthmian script, minimal though it may be, suggests that the script was known to the people of Chiapa de Corzo and was used by them in varying contexts for a significant amount of time.