Judith Leah Cross* Enigma: Aspects of Multimodal Inter-Semiotic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

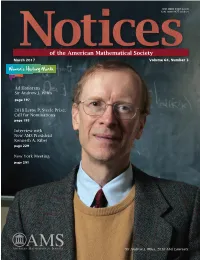

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus the Secrets of Enigma

The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life: Plus The Secrets of Enigma B. Jack Copeland, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The Essential Turing Alan M. Turing The Essential Turing Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma Edited by B. Jack Copeland CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Taipei Toronto Shanghai With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland Portugal Singapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © In this volume the Estate of Alan Turing 2004 Supplementary Material © the several contributors 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

Joan Clarke at Station X

Joan Clarke at Station X Before Joan Clarke worked at Bletchley Park’s Hut 8, she already knew Alan Turing. He was a friend of Joan’s brother. A very intelligent young woman, Joan studied mathematics at Cambridge University’s Newnham College. Gordon Welchman, who was working for the Government Code & Cypher School in the late 1930s, recruited Joan to work at Bletchley Park. He’d been her Geometry supervisor at Cambridge. At the time, women did not typically fill important jobs at Bletchley Park (or anywhere else throughout Britain). So ... at the beginning of her work at Station X ... Joan filled a clerical slot. It took very little time, however, for Joan to get her “own table” inside Hut 8. This promotion effectively placed her on Turing’s code-breaking team. Not only did Joan do great work at Bletchley, by 1944 she was deputy-head of the Hut-8 team. During the early part of her work at Station X, Joan had been promoted to a “Linguist,” even though she wasn’t fluent in other languages. (It was just a way for her to receive better pay for her work.) She once answered a questionnaire with these words: Grade: Linguist, Languages: None. When she first became a Hut-8 code breaker, Joan worked with Alan Turing, Tony Kendrick and Peter Twinn. Their actual work focused on breaking Germany’s Naval Enigma code (which the Station X workers had codenamed “Dolphin”). Joan and Alan Turing became very close friends and, in 1941, the head of Hut 8 asked his friend to become his wife. -

Simply Turing

Simply Turing Simply Turing MICHAEL OLINICK SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2020 by Michael Olinick Cover Illustration by José Ramos Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-37-7 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Contents Praise for Simply Turing vii Other Great Lives x Series Editor's Foreword xi Preface xii Acknowledgements xv 1. Roots and Childhood 1 2. Sherborne and Christopher Morcom 7 3. Cambridge Days 15 4. Birth of the Computer 25 5. Princeton 38 6. Cryptology From Caesar to Turing 44 7. The Enigma Machine 68 8. War Years 85 9. London and the ACE 104 10. Manchester 119 11. Artificial Intelligence 123 12. Mathematical Biology 136 13. Regina vs Turing 146 14. Breaking The Enigma of Death 162 15. Turing’s Legacy 174 Sources 181 Suggested Reading 182 About the Author 185 A Word from the Publisher 186 Praise for Simply Turing “Simply Turing explores the nooks and crannies of Alan Turing’s multifarious life and interests, illuminating with skill and grace the complexities of Turing’s personality and the long-reaching implications of his work.” —Charles Petzold, author of The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour through Alan Turing’s Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine “Michael Olinick has written a remarkably fresh, detailed study of Turing’s achievements and personal issues. -

A Resource for Teachers! How to Use Your Richmond

RICHMOND READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! Level 3 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least three years and up to four years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level B1. SYNOPSIS In 1939, at the beginning of World War II, the British government for homosexual activity. He is offered a choice: prison or pills. He brings together a team of top mathematicians to break the chooses the second. The medication is powerful and dangerous; German Enigma code. The most brilliant of the mathematicians it destroys his mind and his body. Alan commits suicide. is 27 year-old Alan Turing. He has no social skills, however, and soon annoys the rest of the team. He’s a homosexual, at a time THE BACK STORY when homosexual sex was illegal in Britain. Winston Churchill said that Alan Turing made the biggest single Alan wants to build a machine to break the code, an early contribution to the defeat of Nazi Germany. By brilliantly decoding version of a digital computer. The rest of the team think he’s Enigma, Turing gave the Allies a big advantage. Without Turing, wasting time and money, except for Joan Clarke who thinks the Hitler might have won. same way as Alan. The Imitation Game is a dramatised version of Alan Turing’s Joan’s parents are unhappy with her situation as a young story. The real Turing is described as warm and funny, by unmarried woman at Bletchley. Alan rescues the situation by people who knew him. Another important character in the film asking her to marry him. -

Gendering Decryption - Decrypting Gender

1 Gendering decryption - decrypting gender The gender discourse of labour at Bletchley Park 1939-1945 Photograph taken from Smith 2011. Spring 2013 MA thesis (30 hp) Author: Annie Burman Supervisor: Mikael Byström Seminar leader: Torkel Jansson Date of seminar: 4 June 2013 2 Abstract Ever since the British efforts to break Axis codes and ciphers during the Second World War were declassified in the 1970s, the subject of Government Code and Cipher School, the organisation responsible, Bletchley Park, its wartime headquarters, and the impact of the intelligence on the war has fascinated both historians and the general public. However, little attention has been paid to Bletchley Park as a war station where three-quarters of the personnel was female. The purpose of this thesis is to explore the gender discourse of labour at Bletchley Park and how it relates to the wider context of wartime Britain. This is done through the theoretical concepts of gendering (the assignation of a gender to a job, task or object), horizontal gender segregation (the custom of assigning men and women different jobs) and vertical gender segregation (the state where men hold more prestigious positions in the hierarchy than women). The primary sources are interviews, letters and memoirs by female veterans of Bletchley Park, kept in Bletchley Park Trust Archive and the Imperial War Museum’s collections, and printed accounts, in total two monographs and five articles. Surviving official documents from Bletchley Park, now kept in the National Archives, are also utilised. Using accounts created by female veterans themselves as the main source material allows for women’s perspectives to be acknowledged and examined. -

The Imitation Game – Alan & Joan.Pdf

102. STEWART MENZIES I know a lot of spies, Alan. You’re holding on to more secrets than the best of them. Menzies holds up the stolen decrypts. The threat is palpable. ALAN TURING You must promise to get Joan out of prison. STEWART MENZIES She’s at the market. She’ll be back in an hour. I lied. (puts the decrypts into his pocket) I’d better hold on to these. If anyone finds out about them, prison will be the least of her worries. ON ALAN: What choice does he have? He looks down. STEWART MENZIES (CONT’D) Oh Alan. We’re going to have such a wonderful war together. EXT. BLETCHLEY PARK - PATHWAY NEAR HUT 8 - DAY Joan walks towards Hut 8, showing her ID to the new GUARDS who are closely monitoring entry to the Huts. In front of Hut 8, Alan watches her. Steeling himself up for what he has to do. As she approaches, she sees Alan waiting for her. She smiles at him, but he doesn’t return it. Something is wrong. EXT. BLETCHLEY PARK - BEHIND HUT 8 - MOMENTS LATER Alan and Joan talk behind Hut 8. ALAN TURING ... I need you to leave Bletchley. JOAN CLARKE (annoyed) What? ALAN TURING Menzies. I don’t trust... ON ALAN: He wants to tell her, but he can’t. It’s too dangerous. 103. ALAN TURING (CONT’D) ... I don’t think it’s safe here. JOAN CLARKE You think it’s safe somewhere else? ALAN TURING You need to leave, and you need to get very far away from me. -

Jack Copeland on Enigma

Enigma Jack Copeland 1. Turing Joins the Government Code and Cypher School 217 2. The Enigma Machine 220 3. The Polish Contribution, 1932–1940 231 4. The Polish Bomba 235 5. The Bombe and the Spider 246 6. Naval Enigma 257 7. Turing Leaves Enigma 262 1. Turing Joins the Government Code and Cypher School Turing’s personal battle with the Enigma machine began some months before the outbreak of the Second World War.1 At this time there was no more than a handful of people in Britain tackling the problem of Enigma. Turing worked largely in isolation, paying occasional visits to the London oYce of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC & CS) for discussions with Dillwyn Knox.2 In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, Knox had broken the type of Enigma machine used by the Italian Navy.3 However, the more complicated form of Enigma used by the German military, containing the Steckerbrett or plug-board, was not so easily defeated. On 4 September 1939, the day following Chamberlain’s announcement of war with Germany, Turing took up residence at the new headquarters of the Govern- ment Code and Cypher School, Bletchley Park.4 GC & CS was a tiny organization 1 Letters from Peter Twinn to Copeland (28 Jan. 2001, 21 Feb. 2001). Twinn himself joined the attack on Enigma in February 1939. Turing was placed on Denniston’s ‘emergency list’ (see below) in March 1939, according to ‘StaV and Establishment of G.C.C.S.’ (undated), held in the Public Record OYce: National Archives (PRO), Kew, Richmond, Surrey (document reference HW 3/82). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Autism As Metaphor

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Autism as Metaphor: The Affective Regime of Neoliberal Masculinity A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Daniel Michael Ante-Contreras June 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith Harris, Co-Chairperson Dr. Derek Burrill Copyright by Daniel Michael Ante-Contreras 2017 The Dissertation of Daniel Michael Ante-Contreras is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This project was generously supported by a fellowship awarded from the University of California, Riverside Graduate Division for three quarters. Eternal thanks to Sherryl Vint, whose wisdom and willingness to help whenever and wherever were fundamental to shaping this project; many of the ideas in the following pages would not have existed without her insight and mentorship. With gratitude also to Keith Harris, whose suggestions about whiteness and violence were fundamental to the early stages of this project, and to Derek Burrill, who always knew the right time to check in on my writing and my personal well-being. For allowing me to know the fun, play, and love that exists in the world outside of academia, Dakota is owed so much for this project, even if she won’t realize it for many years. My love also goes to Denise, who does more good daily than exists in this entire dissertation and who has kept me accountable to life and reality. Both Dakota and Denise have showed me that this project is so much more than the sum of my ideas. -

Introduction

By what process of becoming did I myself finally appear in the world? Introduction “If you think this is going to be a history lesson, you’ve come to the wrong place.” Or, so says Christopher Morcom at the start of our play. This Actor Packet is the history lesson to accompany Single Carrot’s 2019 production of Pink Milk by Ariel Zetina, directed by Ben Kleymeyer. Here you will find information about the life and work of Alan Turing; elaborations on his relationships with Christopher Morcom, Joan Clarke, Arnold Murray and his parents; and an immersive look into the world in which Alan lived. Comments from me, your dramaturg, are throughout to offer connections between this biographical survey and the text of our play. While Pink Milk is not a history lesson, connecting the journey within the play to the rich facts of Alan’s life can help us map out “the process of becoming” by which Alan the man and Alan the character “finally appear” in both the world we live in and the world we’re creating. Please, feel free to reach out to me any time with questions, research requests, or conversations about what you read here. Thank you for letting me be part of your process of becoming. Many Thanks, Abby NOTES: Photo captions are in the alt-text for each photo. Hover over the photo to read the caption. AT:TE is for Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges; TMWKTM is for The Man Who Knew Too Much by David Leavitt. 1 Table of Contents Introduction Table of Contents Alan Turing Biography Additional Resources Alan Turing Biography Timeline Other Characters Christopher Morcom Mr. -

May 2014 Newsletter

The Felixstowe Society Newsletter Issue Number 106 Contents 1 May 2014 2 The Felixstowe Society 3 Notes from the Chairman 4 Heritage Weekends 4 Speaker Meetings for 2014 5 Visits and Events for 2014 7 Felixstowe Youth Society 9 Felixstowe Walkers 11 ‘European Gateway’ Memorial Plaque 12 Norman Scarfe Eulogy 13 Talk on Felixstowe’s twin towns 14 Talk on design in the historic environment 15 Talk on Felixstowe’s Seafront Gardens 17 Press Release for Felixstory - a dramatic promenade 18 Talk on codes, cyphers and Enigma 19 Research Corner 20 - John Cyril Porte 22 Felixstowe’s Architectural Survey 24 Felixstowe and Offshore Radio 29 Pill box, Ferry Road, Felixstowe 32 Planning Applications 34 Society’s Guided Walks 34 U3A Local History Talks 36 Join The Society Registered Charity No. 277442 Founded 1978 The Felixstowe Society is established for the public benefit of people who either live or work in Felixstowe and Walton. Members are also very welcome from the Trimleys and the surrounding villages. The Society endeavours to: stimulate public interest in these areas, promote high standards of planning and architecture and secure the improvement, protection, development and preservation of the local environment. ! Chairman: Roger Baker, 5 Princes Gardens, Felixstowe, IP11 7RH, 282526 ! Vice Chairman: Philip Hadwen, 54 Fairfield Ave., Felixstowe, IP11 9JJ, 286008 ! Secretary: Trish Hann, 49 Foxgrove Lane, Felixstowe, IP11 7JU, 271902 ! Treasurer: Susanne Barsby, 1 Berners Road, Felixstowe, IP11 7LF, 276602 Membership Subscriptions !!!Annual Membership - single £7!! ! ! !!!Joint Membership - two people at same address £10 !!!Corporate Membership (for local organisations !!!!who wish to support the Society) !!!!Non - commercial £15!! ! ! ! !!! !! Commercial £20!! ! ! ! ! !!! Young people under the age of 18 free!! !!!! ! The subscription runs from the 1 January. -

Alan Turing: Founder of Computer Science

Alan Turing: Founder of Computer Science Jonathan P. Bowen Division of Computer Science and Informatics School of Engineering London South Bank University Borough Road, London SE1 0AA, UK Museophile Limited, Oxford, UK [email protected] http://www.jpbowen.com Abstract. In this paper, a biographical overview of Alan Turing, the 20th cen- tury mathematician, philosopher and early computer scientist, is presented. Tur- ing has a rightful claim to the title of ‘Father of modern computing’. He laid the theoretical groundwork for a universal machine that models a computer in its most general form before World War II. During the war, Turing was instru- mental in developing and influencing practical computing devices that have been said to have shortened the war by up to two years by decoding encrypted enemy messages that were generally believed to be unbreakable. After the war, he was involved with the design and programming of early computers. He also wrote foundational papers in the areas of what are now known as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and mathematical biology shortly before his untimely death. The paper also considers Turing’s subsequent influence, both scientifically and culturally. 1 Prologue Alan Mathison Turing [8,23,33] was born in London, England, on 23 June 1912. Ed- ucated at Sherborne School in Dorset, southern England, and at King’s College, Cam- bridge, he graduated in 1934 with a degree in mathematics. Twenty years later, after a short but exceptional career, he died on 7 June 1954 in mysterious circumstances. He is lauded by mathematicians, philosophers, and computer sciences, as well as increasingly the public in general.