Jack Copeland on Enigma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Turing Guide

The Turing Guide Edited by Jack Copeland, Jonathan Bowen, Mark Sprevak, and Robin Wilson • A complete guide to one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century • Covers aspects of Turing’s life and the wide range of his intellectual activities • Aimed at a wide readership • This carefully edited resource written by a star-studded list of contributors • Around 100 illustrations This carefully edited resource brings together contributions from some of the world’s leading experts on Alan Turing to create a comprehensive guide that will serve as a useful resource for researchers in the area as well as the increasingly interested general reader. “The Turing Guide is just as its title suggests, a remarkably broad-ranging compendium of Alan Turing’s lifetime contributions. Credible and comprehensive, it is a rewarding exploration of a man, who in his life was appropriately revered and unfairly reviled.” - Vint Cerf, American Internet pioneer JANUARY 2017 | 544 PAGES PAPERBACK | 978-0-19-874783-3 “The Turing Guide provides a superb collection of articles £19.99 | $29.95 written from numerous different perspectives, of the life, HARDBACK | 978-0-19-874782-6 times, profound ideas, and enormous heritage of Alan £75.00 | $115.00 Turing and those around him. We find, here, numerous accounts, both personal and historical, of this great and eccentric man, whose life was both tragic and triumphantly influential.” - Sir Roger Penrose, University of Oxford Ordering Details ONLINE www.oup.com/academic/mathematics BY TELEPHONE +44 (0) 1536 452640 POSTAGE & DELIVERY For more information about postage charges and delivery times visit www.oup.com/academic/help/shipping/. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CURVE/open How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2014, 'How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park' History of Science, vol 52, no. 2, pp. 200-222 https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0073275314529861 DOI 10.1177/0073275314529861 ISSN 0073-2753 ESSN 1753-8564 Publisher: Sage Publications Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Mechanising the Information War – Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Christopher Smith Abstract The Bombe machine was a key device in the cryptanalysis of the ciphers created by the machine system widely employed by the Axis powers during the Second World War – Enigma. -

Stdin (Ditroff)

Notes to accompany four Alan Turing videos 1. General The recent (mid-November 2014) release of The Imitation Game movie has caused the com- prehensive Alan Hodges biography of Turing to be reprinted in a new edition [1]. This biog- raphy was the basis of the screenplay for the movie. A more recent biography, by Jack Copeland [2], containing some new items of information, appeared in 2012. A more techni- cal work [3], also by Jack Copeland but with contributed chapters from other people, appeared in 2004. 2. The Princeton Years 1936–38. Alan Turing spent the years from 1936–38 at Princeton University studying mathematical logic with Prof. Alonzo Church. During that time Church persuaded Turing to extend the Turing Machine ideas in the 1936 paper and to write the results up as a Princeton PhD. You can now obtaing a copy of that thesis very easily [4] and this published volume contains extra chapters by Andrew Appel and Solomon Feferman, setting Turing’s work in context. (Andrew Appel is currently Chair of the Computer Science Dept. at Princeton) 3. Cryptography and Bletchley park There are many texts available on cryptography in general and Bletchley Park in particu- lar. A good introductory text for the entire subject is “The Code Book” by Simon Singh [5] 3.1. Turing’s Enigma Problem There are now a large number of books about the deciphering of Enigma codes, both in Hut 6 and Hut 8. A general overview is given by “Station X” by Michael Smith [6] while a more detailed treatment, with several useful appendices, can be found in the book by Hugh Sebag-Montefiore [7]. -

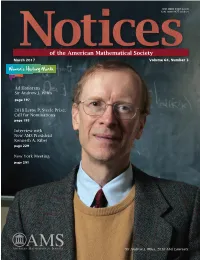

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

The Imagination Game Storia E Fantasia in the Imitation Game

The Imagination Game storia e fantasia in The Imitation Game Cap. 2: Bletchley Park e Ultra Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 1/28 Bletchley Park e Ultra • Un’organizzazione poderosa • Bletchley Park • I luoghi, le strutture, le procedure • I meccanismi e gli appoggi • Il personale, le (tante) donne di BP • Ultra • Cos’era, come era nascosto • L’impatto sul conflitto, episodi e numeri Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 2/28 A lezione dai Polacchi • 1919, Biuro Szyfrów • Militari, Kowalewski, e matematici, Mazurkiewicz, Sierpiński, Leśniewski • Nel 1938 il 75% dei messaggi tedeschi intercettati era decifrato (Rejewski, Zygalski, Różycki) • Dopo il ’39 PC Bruno, Cadix, Boxmoor • In Inghilterra • Room40 (1914), GC&CS (1919), BP (1938) • Parigi (gennaio ’39), con Francesi e Polacchi • Pyry vicino Varsavia (luglio ’39) Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 3/28 Un posto strategico Bletchley Park - Gayhurst - Wavendon - Stanmore - Eastcote - Adstock Cambridge Banbury Letchworth Oxford London Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 4/28 Bletchley Park, 1942ca Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 5/28 Nel film, ci somiglia... Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 6/28 … ma non è Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 7/28 Il nume tutelare • 1941.10.21: Action this day! • In un momento di successo • Dopo una visita di Churchill • Le Bombe ci sono, mancano persone • Garanzie per i tecnici BTM • Personale per la catena • Intercettazione in grande • Risorse per una pesca industriale • Un po’ come “Echelon” Giovanni A. Cignoni – Progetto HMR 8/28 Il personale • Una grande industria • Da 9000 a 10000 persone, centinaia di macchine • Piuttosto stabile, circa 12000 nomi • Escluso l’indotto, fornitori e logistica • Reclutamento • Inizialmente diretto, da persona a persona • Poi attraverso controlli e selezioni metodiche • Soprattutto nell’ambito delle leve militari • Ma con un occhio anche ai civili Giovanni A. -

Polska Myśl Techniczna W Ii Wojnie Światowej

CENTRALNA BIBLIOTEKA WOJSKOWA IM. MARSZAŁKA JÓZEFA PIŁSUDSKIEGO POLSKA MYŚL TECHNICZNA W II WOJNIE ŚWIATOWEJ W 70. ROCZNICĘ ZAKOŃCZENIA DZIAŁAŃ WOJENNYCH W EUROPIE MATERIAŁY POKONFERENCYJNE poD REDAkcJą NAUkoWą DR. JANA TARCZYńSkiEGO WARSZAWA 2015 Konferencja naukowa Polska myśl techniczna w II wojnie światowej. W 70. rocznicę zakończenia działań wojennych w Europie Komitet naukowy: inż. Krzysztof Barbarski – Prezes Instytutu Polskiego i Muzeum im. gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie dr inż. Leszek Bogdan – Dyrektor Wojskowego Instytutu Techniki Inżynieryjnej im. profesora Józefa Kosackiego mgr inż. Piotr Dudek – Prezes Stowarzyszenia Techników Polskich w Wielkiej Brytanii gen. dyw. prof. dr hab. inż. Zygmunt Mierczyk – Rektor-Komendant Wojskowej Akademii Technicznej im. Jarosława Dąbrowskiego płk mgr inż. Marek Malawski – Szef Inspektoratu Implementacji Innowacyjnych Technologii Obronnych Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej mgr inż. Ewa Mańkiewicz-Cudny – Prezes Federacji Stowarzyszeń Naukowo-Technicznych – Naczelnej Organizacji Technicznej prof. dr hab. Bolesław Orłowski – Honorowy Członek – założyciel Polskiego Towarzystwa Historii Techniki – Instytut Historii Nauki Polskiej Akademii Nauk kmdr prof. dr hab. Tomasz Szubrycht – Rektor-Komendant Akademii Marynarki Wojennej im. Bohaterów Westerplatte dr Jan Tarczyński – Dyrektor Centralnej Biblioteki Wojskowej im. Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego prof. dr hab. Leszek Zasztowt – Dyrektor Instytutu Historii Nauki Polskiej Akademii Nauk dr Czesław Andrzej Żak – Dyrektor Centralnego Archiwum Wojskowego im. -

Ted Nelson History of Computing

History of Computing Douglas R. Dechow Daniele C. Struppa Editors Intertwingled The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson History of Computing Founding Editor Martin Campbell-Kelly, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK Series Editor Gerard Alberts, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Advisory Board Jack Copeland, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Ulf Hashagen, Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany John V. Tucker, Swansea University, Swansea, UK Jeffrey R. Yost, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA The History of Computing series publishes high-quality books which address the history of computing, with an emphasis on the ‘externalist’ view of this history, more accessible to a wider audience. The series examines content and history from four main quadrants: the history of relevant technologies, the history of the core science, the history of relevant business and economic developments, and the history of computing as it pertains to social history and societal developments. Titles can span a variety of product types, including but not exclusively, themed volumes, biographies, ‘profi le’ books (with brief biographies of a number of key people), expansions of workshop proceedings, general readers, scholarly expositions, titles used as ancillary textbooks, revivals and new editions of previous worthy titles. These books will appeal, varyingly, to academics and students in computer science, history, mathematics, business and technology studies. Some titles will also directly appeal to professionals and practitioners -

Alan Turing's Forgotten Ideas

Alan Turing, at age 35, about the time he wrote “Intelligent Machinery” Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc. lan Mathison Turing conceived of the modern computer in 1935. Today all digital comput- Aers are, in essence, “Turing machines.” The British mathematician also pioneered the field of artificial intelligence, or AI, proposing the famous and widely debated Turing test as a way of determin- ing whether a suitably programmed computer can think. During World War II, Turing was instrumental in breaking the German Enigma code in part of a top-secret British operation that historians say short- ened the war in Europe by two years. When he died Alan Turing's at the age of 41, Turing was doing the earliest work on what would now be called artificial life, simulat- ing the chemistry of biological growth. Throughout his remarkable career, Turing had no great interest in publicizing his ideas. Consequently, Forgotten important aspects of his work have been neglected or forgotten over the years. In particular, few people— even those knowledgeable about computer science— are familiar with Turing’s fascinating anticipation of connectionism, or neuronlike computing. Also ne- Ideas glected are his groundbreaking theoretical concepts in the exciting area of “hypercomputation.” Accord- ing to some experts, hypercomputers might one day in solve problems heretofore deemed intractable. Computer Science The Turing Connection igital computers are superb number crunchers. DAsk them to predict a rocket’s trajectory or calcu- late the financial figures for a large multinational cor- poration, and they can churn out the answers in sec- Well known for the machine, onds. -

Judith Leah Cross* Enigma: Aspects of Multimodal Inter-Semiotic

91 Judith Leah Cross* Enigma: Aspects of Multimodal Inter-Semiotic Translation Abstract Commercial and creative perspectives are critical when making movies. Deciding how to select and combine elements of stories gleaned from books into multimodal texts results in films whose modes of image, words, sound and movement interact in ways that create new wholes and so, new stories, which are more than the sum of their individual parts. The Imitation Game (2014) claims to be based on a true story recorded in the seminal biography by Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma (1983). The movie, as does its primary source, endeavours to portray the crucial role of Enigma during World War Two, along with the tragic fate of a key individual, Alan Turing. The film, therefore, involves translation of at least two “true” stories, making the film a rich source of data for this paper that addresses aspects of multimodal inter-semiotic translations (MISTs). Carefully selected aspects of tales based on “true stories” are interpreted in films; however, not all interpretations possess the same degree of integrity in relation to their original source text. This paper assumes films, based on stories, are a form of MIST, whose integrity of translation needs to be assessed. The methodology employed uses a case-study approach and a “grid” framework with two key critical thinking (CT) standards: Accuracy and Significance, as well as a scale (from “low” to “high”). This paper offers a stretched and nuanced understanding of inter-semiotic translation by analysing how multimodal strategies are employed by communication interpretants. Keywords accuracy; critical thinking; inter-semiotic; multimodal; significance; translation; truth 1. -

Polish Mathematicians Finding Patterns in Enigma Messages

Fall 2006 Chris Christensen MAT/CSC 483 Machine Ciphers Polyalphabetic ciphers are good ways to destroy the usefulness of frequency analysis. Implementation can be a problem, however. The key to a polyalphabetic cipher specifies the order of the ciphers that will be used during encryption. Ideally there would be as many ciphers as there are letters in the plaintext message and the ordering of the ciphers would be random – an one-time pad. More commonly, some rotation among a small number of ciphers is prescribed. But, rotating among a small number of ciphers leads to a period, which a cryptanalyst can exploit. Rotating among a “large” number of ciphers might work, but that is hard to do by hand – there is a high probability of encryption errors. Maybe, a machine. During World War II, all the Allied and Axis countries used machine ciphers. The United States had SIGABA, Britain had TypeX, Japan had “Purple,” and Germany (and Italy) had Enigma. SIGABA http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIGABA 1 A TypeX machine at Bletchley Park. 2 From the 1920s until the 1970s, cryptology was dominated by machine ciphers. What the machine ciphers typically did was provide a mechanical way to rotate among a large number of ciphers. The rotation was not random, but the large number of ciphers that were available could prevent depth from occurring within messages and (if the machines were used properly) among messages. We will examine Enigma, which was broken by Polish mathematicians in the 1930s and by the British during World War II. The Japanese Purple machine, which was used to transmit diplomatic messages, was broken by William Friedman’s cryptanalysts. -

Idle Motion's That Is All You Need to Know Education Pack

Idle Motion’s That is All You Need to Know Education Pack Idle Motion create highly visual theatre that places human stories at the heart of their work. Integrating creative and playful stagecraft with innovative video projection and beautiful physicality, their productions are humorous, evocative and sensitive pieces of theatre which leave a lasting impression on their audiences. From small beginnings, having met at school, they have grown rapidly as a company over the last six years, producing five shows that have toured extensively both nationally and internationally to critical acclaim. Collaborative relationships are at the centre of all that they do and they are proud to be an Associate Company of the New Diorama Theatre and the Oxford Playhouse. Idle Motion are a young company with big ideas and a huge passion for creating exciting, beautiful new work. That is All You Need to Know ‘That Is All You Need To Know’ is Idle Motion’s fifth show. We initially wanted to make a show based on the life of Alan Turing after we were told about him whilst researching chaos theory for our previous show ‘The Seagull Effect’. However once we started to research the incredible work he did during the Second World War at Bletchley Park and visited the site itself we soon realised that Bletchley Park was full of astounding stories and people. What stood out for us as most remarkable was that the thousands of people who worked there kept it all a secret throughout the war and for most of their lives. This was a story we wanted to tell. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan)