Engineering Your Own Soul: Theory and Practice in Communist Biography and Autobiography & Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(WA) from 1938 to 1980 and Its Role in the Cultural Life of Perth

The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. Patricia Kotai-Ewers Bachelor of Arts, Master of Philosophy (UWA) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University November 2013 ABSTRACT The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. By the mid-1930s, a group of distinctly Western Australian writers was emerging, dedicated to their own writing careers and the promotion of Australian literature. In 1938, they founded the Western Australian Section of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. This first detailed study of the activities of the Fellowship in Western Australia explores its contribution to the development of Australian literature in this State between 1938 and 1980. In particular, this analysis identifies the degree to which the Fellowship supported and encouraged individual writers, promoted and celebrated Australian writers and their works, through publications, readings, talks and other activities, and assesses the success of its advocacy for writers’ professional interests. Information came from the organisation’s archives for this period; the personal papers, biographies, autobiographies and writings of writers involved; general histories of Australian literature and cultural life; and interviews with current members of the Fellowship in Western Australia. These sources showed the early writers utilising the networks they developed within a small, isolated society to build a creative community, which welcomed artists and musicians as well as writers. The Fellowship lobbied for a wide raft of conditions that concerned writers, including free children’s libraries, better rates of payment and the establishment of the Australian Society of Authors. -

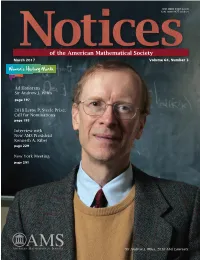

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

A Career in Writing

A Career in Writing Judah Waten and the Cultural Politics of a Literary Career David John Carter MA Dip Ed (Melb) Thesis submitted as total fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts, Deakin University, March 1993. Summary This thesis examines the literary career of Judah Waten (1911-1985) in order to focus on a series of issues in Australian cultural history and theory. The concept of the career is theorised as a means of bringing together the textual and institutional dimensions of writing and being a writer in a specific cultural economy. The guiding question of the argument which re-emerges in different ways in each chapter is: in what ways was it possible to write and to be a writer in a given time and place? Waten's career as a Russian-born, Jewish, Australian nationalist, communist and realist writer across the middle years of this century is, for the purposes of the argument, at once usefully exemplary and usefully marginal in relation to the literary establishment. His texts provide the central focus for individual chapters; at the same time each chapter considers a specific historical moment and a specific set of issues for Australian cultural history, and is to this extent self-contained. Recent work in narrative theory, literary sociology and Australian literary and cultural studies is brought together to revise accepted readings of Waten's texts and career, and to address significant absences or problems in Australian cultural history. The sequence of issues shaping Waten's career in -

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St. Petersburg to Chicago Pamphlets Explanatory Power I 6 fDK246.S2 M. Dobrov Chto takoe burzhuaziia? [What is the Bourgeoisie?] Petrograd: Petrogr. Torg. Prom. Soiuz, tip. “Kopeika,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 39 fDK246.S2 S.K. Neslukhovskii Chto takoe sotsializm? [What is Socialism?] Petrograd: K-vo “Svobodnyi put’”, [n.d.] Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 10 fDK246.S2 Aleksandra Kollontai Kto takie sotsial-demokraty i chego oni khotiat’? [Who Are the Social Democrats and What Do They Want?] Petrograd: Izdatel’stvo i sklad “Kniga,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets I 7 fDK246.S2 Vatin (V. A. Bystrianskii) Chto takoe kommuna? (What is a Commune?) Petrograd: Petrogradskogo Soveta Rabochikh i Krasnoarmeiskikh Deputatov, 1918 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 32 fDK246.S2 L. Kin Chto takoe respublika? [What is a Republic?] Petrograd: Revoliutsionnaia biblioteka, 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 31 fDK246.S2 G.K. Kryzhitskii Chto takoe federativnaia respublika? (Rossiiskaia federatsiia) [What is a Federal Republic? (The Russian Federation)] Petrograd: Znamenskaia skoropechatnaia, 1917 1 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E42 fDK246.S2 O.A. Vol’kenshtein (Ol’govich): Federalizm v Rossii [Federalism in Russia] Knigoizdatel’stvo “Luch”, [n.d.] fDK246.S2 E33 I.N. Ignatov Gosudarstvennyi stroi Severo-Amerikanskikh Soedinenykh shtatov: Respublika [The Form of Government of the United States of America: Republic] Moscow: t-vo I. D. Sytina, 1917 fDK246.S2 E34 K. Parchevskii Polozhenie prezidenta v demokraticheskoi respublike [The Position of the President in a Democratic Republic] Petrograd: Rassvet, 1917 fDK246.S2 H35 Prof. V.V. -

04 Chapters 8-Bibliography Burns

159 CHAPTER 8 THE BRISBANE LINE CONTROVERSY Near the end of March 1943 nineteen members of the UAP demanded Billy Hughes call a party meeting. Hughes had maintained his hold over the party membership by the expedient of refusing to call members 1a together. For months he had then been able to avoid any leadership challenge. Hughes at last conceded to party pressure, and on 25 March, faced a leadership spill, which he believed was inspired by Menzies. 16 He retained the leadership by twenty-four votes to fifteen. The failure to elect a younger and more aggressive leader - Menzies - resulted in early April in the formation by the dissenters of the National Service Group, which was a splinter organisation, not a separate party. Menzies, and Senators Leckie and Spicer from Victoria, Cameron, Duncan, Price, Shcey and Senators McLeary, McBride, the McLachlans, Uphill and Wilson from South Australia, Beck and Senator Sampson from Tasmania, Harrison from New South Wales and Senator Collett from Western Australia comprised the group. Spender stood aloof. 1 This disturbed Ward. As a potential leader of the UAP Menzies was likely to be more of an electoral threat to the ALP, than Hughes, well past his prime, and in the eyes of the public a spent political force. Still, he was content to wait for the appropriate moment to discredit his old foe, confident he had the ammunition in his Brisbane Line claims. The Brisbane Line Controversy Ward managed to verify that a plan existed which had intended to abandon all of Australia north of a line north of Brisbane and following a diagonal course to a point north of Adelaide to be abandoned to the enemy, - the Maryborough Plan. -

Judith Leah Cross* Enigma: Aspects of Multimodal Inter-Semiotic

91 Judith Leah Cross* Enigma: Aspects of Multimodal Inter-Semiotic Translation Abstract Commercial and creative perspectives are critical when making movies. Deciding how to select and combine elements of stories gleaned from books into multimodal texts results in films whose modes of image, words, sound and movement interact in ways that create new wholes and so, new stories, which are more than the sum of their individual parts. The Imitation Game (2014) claims to be based on a true story recorded in the seminal biography by Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma (1983). The movie, as does its primary source, endeavours to portray the crucial role of Enigma during World War Two, along with the tragic fate of a key individual, Alan Turing. The film, therefore, involves translation of at least two “true” stories, making the film a rich source of data for this paper that addresses aspects of multimodal inter-semiotic translations (MISTs). Carefully selected aspects of tales based on “true stories” are interpreted in films; however, not all interpretations possess the same degree of integrity in relation to their original source text. This paper assumes films, based on stories, are a form of MIST, whose integrity of translation needs to be assessed. The methodology employed uses a case-study approach and a “grid” framework with two key critical thinking (CT) standards: Accuracy and Significance, as well as a scale (from “low” to “high”). This paper offers a stretched and nuanced understanding of inter-semiotic translation by analysing how multimodal strategies are employed by communication interpretants. Keywords accuracy; critical thinking; inter-semiotic; multimodal; significance; translation; truth 1. -

MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: Research Material and Indexes, 1964-1968

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY………………………………………….......page 5 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT……………………………..page 5 ACCESS TO COLLECTION………………………………………….…page 6 COLLECTION OVERVIEW……………………………………………..page 7 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………...………………page 10 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………...page 12 Series 1 Research material files Folder 1/1 Abstracts Folder 1/2 Agriculture, c.1963-1964 Folder 1/3 Arts, 1936-1965 Folder 1/4 Attitudes, c.1919-1967 Folder 1/5 Bibliographies, c.1960s MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 Folder 1/6 Case Histories, c.1934-1966 Folder 1/7 Cooperatives, c.1954-1965. Folder 1/8 Councils, 1961-1966 Folder 1/9 Courts, Folio A-U, 1-20, 1907-1966 Folder 1/10-11 Civic Rights, Files 1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/12 Crime, 1964-1967 Folder 1/13 Customs – Native, 1931-1965 Folder 1/14 Demography – Census 1961 – Australia – full-blood Aboriginals Folder 1/15 Demography, 1931-1966 Folder 1/16 Discrimination, 1921-1967 Folder 1/17 Discrimination – Freedom Ride: press cuttings, Feb-Jun 1965 Folder 1/18-19 Economy, Pts.1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/20-21 Education, Files 1 & 2, 1936-1967 Folder 1/22 Employment, 1924-1967 Folder 1/23 Family, 1965-1966 -

Full Thesis Draft No Pics

A whole new world: Global revolution and Australian social movements in the long Sixties Jon Piccini BA Honours (1st Class) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of History, Philosophy, Religion & Classics Abstract This thesis explores Australian social movements during the long Sixties through a transnational prism, identifying how the flow of people and ideas across borders was central to the growth and development of diverse campaigns for political change. By making use of a variety of sources—from archives and government reports to newspapers, interviews and memoirs—it identifies a broadening of the radical imagination within movements seeking rights for Indigenous Australians, the lifting of censorship, women’s liberation, the ending of the war in Vietnam and many others. It locates early global influences, such as the Chinese Revolution and increasing consciousness of anti-racist struggles in South Africa and the American South, and the ways in which ideas from these and other overseas sources became central to the practice of Australian social movements. This was a process aided by activists’ travel. Accordingly, this study analyses the diverse motives and experiences of Australian activists who visited revolutionary hotspots from China and Vietnam to Czechoslovakia, Algeria, France and the United States: to protest, to experience or to bring back lessons. While these overseas exploits, breathlessly recounted in articles, interviews and books, were transformative for some, they also exposed the limits of what a transnational politics could achieve in a local setting. Australia also became a destination for the period’s radical activists, provoking equally divisive responses. -

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

Cold War PS MB 10/27/03 8:28 PM Page 146 House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) Excerpt from “One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism in the U.S.A.” Reprinted from Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts From Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, published in 1971 “[Question:] Why ne Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- shouldn’t I turn “O nism in the U.S.A.” was the first in a series of pam- Communist? [Answer:] phlets put out by the House Un-American Activities Commit- You know what the United tee (HUAC) to educate the American public about communism in the United States. In May 1938, U.S. represen- States is like today. If you tative Martin Dies (1900–1972) of Texas managed to get his fa- want it exactly the vorite House committee, HUAC, funded. It had been inactive opposite, you should turn since 1930. The HUAC was charged with investigation of sub- Communist. But before versive activities that posed a threat to the U.S. government. you do, remember you will lose your independence, With the HUAC revived, Dies claimed to have gath- ered knowledge that communists were in labor unions, gov- your property, and your ernment agencies, and African American groups. Without freedom of mind. You will ever knowing why they were charged, many individuals lost gain only a risky their jobs. In 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration membership in a Act, known as the Smith Act. The act made it illegal for an conspiracy which is individual to be a member of any organization that support- ruthless, godless, and ed a violent overthrow of the U.S. -

The 1952 Youth Carnival for Peace and Friendship

Community Carnival or Cold War Strategy? The 1952 Youth Carnival for Peace and Friendship Phillip Deery Victoria University of Technology In March 1952, four youthful and possibly maverick members of the top-down institutional emphasis of the 'older' generation of the NSW Police Force contacted Audrey Blake, the national secretary historians of the communist movement for whom the question of of the Eureka Youth League [EYL]. As a team, they said, they wished Soviet control was pivotal, these 'new historians' examine particular to enter several sporting events in the forthcoming Youth Carnival communities, particular working class cultures, and particular sub for Peace and Friendship. The national executive of the EYL, which groupings within the Party and how each operated within a broader helped organise the carnival, reported that, at first, it 'regarded this environment. This paper does not seek to whitewash the Communist request with considerable suspicion, but after discussion with the Party's authoritarian internal structure and its subservience to the policemen, found they had a genuine interest in the purpose of the Soviet Union, but it does seek to place the 1952 Youth Carnival Carnival, namely Youth activity and Peace'. I This request, and its against a backdrop of much broader community involvement than a response, exemplify two themes of this paper. First, the extent to Manichean view of the Cold War suggests. which the Carnival, one of the longest, largest and most logistically The 1952 Sydney Carnival was the first of its kind outside Eastern complex carnivals ever held in Australia, embraced broad community Europe. Its immediate inspiration was the 3rd World Youth Festival interests, extending even to the police services. -

The British Radical Literary Tradition As the Seminal Force in the Development of Adult Education, Its Australian Context, and the Life and Work of Eric Lambert

Writing Revolution: The British Radical Literary Tradition as the Seminal Force in the Development of Adult Education, its Australian Context, and the Life and Work of Eric Lambert Author Merlyn, Teri Published 2004 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Vocational, Technology and Arts Education DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3245 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367384 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Writing Revolution: The British Radical Literary tradition as the Seminal Force in the Development of Adult Education, its Australian Context, and the Life and Work of Eric Lambert By Teri Merlyn BA, Grad.Dip.Cont.Ed. Volume One School of Vocational, Technology and Arts Education Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date:……………………………………………………………………… Abstract This thesis tells the story of an historical tradition of radical literacy and literature that is defined as the British radical literary tradition. It takes the meaning of literature at its broadest understanding and identifies the literary and educational relations of what E P Thompson terms ‘the making of the English working class’ through its struggle for literacy and freedom. The study traces the developing dialectic of literary radicalism and the emergent hegemony of capitalism through the dissemination of radical ideas in literature and a groundswell of public literacy. The proposed radical tradition is defined by the oppositional stance of its participants, from the radical intellectual’s critical texts to the striving for literacy and access to literature by working class people. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief.