Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Group on Human Sexuality

IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page i The House of Bishops Working Group on human sexuality Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page ii Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page iii Report of the House of Bishops Working Group on human sexuality November 2013 Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page iv Church House Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this Church House publication may be reproduced or Great Smith Street stored or transmitted by any means London or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, SW1P 3AZ recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought ISBN 978 0 7151 4437 4 (Paperback) from [email protected] 978 0 7151 4438 1 (CoreSource EBook) 978 0 7151 4439 8 (Kindle EBook) Unless otherwise indicated, the Scripture quotations contained GS 1929 herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright Published 2013 for the House © 1989, by the Division of Christian of Bishops of the General Synod Education of the National Council of the Church of England by Church of the Churches of Christ in the -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

HARDWICK and Historiographyt

HARDWICK AND HISTORIOGRAPHYt William N. Eskridge, Jr.* In this article, originally presented as a David C. Baum Me- morial Lecture on Civil Liberties and Civil Rights at the University of Illinois College of Law, Professor William Eskridge critically examines the holding of the United States Supreme Court in Bow- ers v. Hardwick, where the Court held, in a 5-4 opinion, that "ho- mosexual sodomy" between consenting adults in the home did not enjoy a constitutionalprotection of privacy and could be criminal- ized by state statute. Because the Court's opinion critically relied on an originalistinterpretation of the Constitution, Professor Es- kridge reconstructs the history and jurisprudence of sodomy laws in the United States until the present day. He argues that the Hard- wick ruling rested upon an anachronistictreatment of sodomy reg- ulation at the time of the Fifth (1791) or Fourteenth (1868) Amendments. Specifically, the Framersof those amendments could not have understood sodomy laws as regulating oral intercourse (Michael Hardwick's crime) or as focusing on "homosexual sod- omy" (the Court's focus). Moreover, the goal of sodomy regula- tion before this century was to assure that sexual intimacy occur in the context of procreative marriage,an unconstitutional basis for criminal law under the Court's privacy jurisprudence. In short, Professor Eskridge suggests that the Court's analysis of sodomy laws had virtually no connection with the historical understanding of eighteenth or mid-nineteenth century regulators. Rather, the Court's analysis reflected the Justices' own preoccupation with "homosexual sodomy" and their own nervousness about the right of privacy previous Justices had found in the penumbras of the Constitution. -

Same-Sex Marriage

Relate policy position June 2014 Evidence suggests that hostile and unsupportive environments can lead to same-sex relationships being more likely to breakdown. Relate welcomes the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013 as a positive step towards promoting equality and reducing institutional discrimination towards same-sex couples and their relationships. Relate aims to provide effective and inclusive services supporting same-sex couples at all stages of their relationships. www.relate.org.uk For decades Relate has offered services to same-sex and opposite-sex couples alike. We believe in supporting relationships of all types and promoting good quality, strong and stable relationships. We recognise the importance of equal legal recognition of relationships, and also note the negative impact that discrimination, including institutional discrimination, can have on same-sex couples’ well-being. As such we welcome the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013 as a positive step towards promoting equality and reducing institutional discrimination directed towards same-sex couples and their relationships. 1. Relate believes in the importance of good quality, strong and stable relationships for both same-sex and opposite-sex couples alike. The evidence says that what matters most is the quality of relationships, not their legal form. 2. Relate believes that that same-sex couples should be able to have their relationships legally recognised if they choose to. This is important to combat stigma and promote a culture change where same-sex relationships are given equal value (to opposite sex relationships) and support is available for those in same sex relationships. 3. Relate aims to provide effective and inclusive services supporting relationships for every section of the community, including same-sex couples, at all stages of their relationships. -

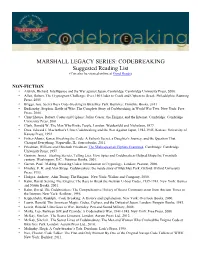

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Friday Volume 619 20 January 2017 No. 95 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Friday 20 January 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1179 20 JANUARY 2017 1180 House of Commons Merchant Shipping (Homosexual Conduct) Bill Friday 20 January 2017 Second Reading. The House met at half-past Nine o’clock 9.54 am John Glen (Salisbury) (Con): I beg to move, That the PRAYERS Bill be now read a Second time. I am very pleased to bring the Bill to the House because, by repealing sections 146(4) and 147(3) of the [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, it completes the removal of historical provisions that penalised 9.34 am homosexual activity. I am proud to do so because of my commitment to justice and opposition to unjustified Mr David Nuttall (Bury North) (Con): I beg to move, discrimination. That the House sit in private. When it comes to employment, in the merchant navy Question put forthwith (Standing Order No. 163). or anywhere else, what matters is a person’s ability to do The House proceeded to a Division. the job—not their gender, age, ethnicity, religion or sexuality. Hon. Members across the House share that Mr Speaker: Would the Serjeant care to investigate commitment. Manywill be surprised—astonished, even—to the delay in the voting Lobby? learn that this anomaly still remains on the statute book. -

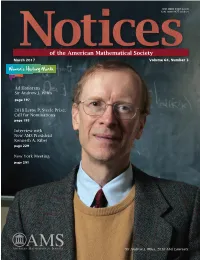

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

Yuill, Richard Alexander (2004) Male Age-Discrepant Intergenerational Sexualities and Relationships

Yuill, Richard Alexander (2004) Male age-discrepant intergenerational sexualities and relationships. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2795/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Male Age-Discrepant Intergenerational Sexualities and Relationships Volume One Chapters One-Thirteen Richard Alexander Yuill A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Applied Social Sciences Faculty of Social Sciences October 2004 © Richard Alexander Yuill 2004 Author's Declaration I declare that the contents of this thesis are all my own work. Richard Alexander Yuill 11 CONTENTS Page No. Acknowledgements Xll Abstract Xll1-X1V Introduction 1-9 Chapter One Literature Review 10-68 1.1 Research problem and overview 10 1.2 Adult sexual attraction to children (paedophilia) 10-22 and young people (ephebophilia) 1.21 Later Transformations (1980s-2000s) Howitt's multi-disciplinary study Ethics Criminological -

Universalization of LGBTQ Rights

ODUMUNC 2017 Issue Brief Third Committee: Social, Humanitarian, and Cultural Universalization of LGBTQ Rights by Tiana Bailey Old Dominion University Model United Nations Society are working to extend those rights to protect Introduction individual gender identity globally. But reverse processes also can be seen. Other UN Member The question of whether and how to States have established laws to bloc such acknowledge and protect individual rights over reforms, including prohibiting public discussion gender identity is a difficult issue for the of homosexuality and trans-gender rights and international community. Although UN Member criminalizing same-sex relationships. States have dealt with this and related policy issues for hundreds of years, traditionally state policy meant persecution. Since the mid- Twentieth Century, partially in response to the persecution and killing of Fascist and Nazi governments in the 1930s and ‘40s, policy has shifted to include greater protection of their rights as equal citizens. A major issue for the international community today is whether and how to best assure those rights, whether outright universalization of LGBTQ rights is feasible, and how to achieve it. Not only are more UN Member States seeking to universalize their rights, they seek to apply them to a growing group of people. This is seen in the rising importance of the abbreviation LGBTQ, originated in the 1990s to replace what was formerly known as ‘the gay community’, and include more diverse groups. LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (and/or questioning) individuals/identities. What At the worst, discrimination and persecution all share are non-heterosexual perspectives and leads to violent attacks. -

Religion, the Rule of Law and Discrimination Transcript

Religion, the Rule of Law and Discrimination Transcript Date: Thursday, 26 June 2014 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 26 June 2014 Religion, the Rule of Law and Discrimination The Rt Hon. Sir Terence Etherton Chancellor of the High Court of England and Wales 1. One of the most difficult and contentious areas of our law today is the resolution of disputes generated by a conflict between, on the one hand, the religious beliefs of an individual and, on the other hand, actions which that individual is required to take, whether that requirement is by a public body, a private employer or another individual. The problem is particularly acute where the conflict is directly or indirectly between one individual’s religious beliefs and another’s non-religious human rights.[1] 2. It is a subject that affects many countries as they have become more liberal, multicultural and secular.[2] The issues in countries which are members of the Council of Europe and of the European Union, like England and Wales, are affected by European jurisprudence as well as national law. The development of the law in England is of particular interest because the Protestant Church is the established Church of England but the protection for secular and other non-Protestant minorities has progressed at a pace and in a way that would have been beyond the comprehension of most members of society, including judges and politicians, before the Second World War. 3. This subject is large and complex and the law relevant to it is growing at a remarkably fast pace.[3] For the purpose of legal commentary, it falls naturally into two parts: (1) tracing the legal history and reasons for the developments I have mentioned, and (2) analysing the modern jurisprudence. -

Judith Leah Cross* Enigma: Aspects of Multimodal Inter-Semiotic

91 Judith Leah Cross* Enigma: Aspects of Multimodal Inter-Semiotic Translation Abstract Commercial and creative perspectives are critical when making movies. Deciding how to select and combine elements of stories gleaned from books into multimodal texts results in films whose modes of image, words, sound and movement interact in ways that create new wholes and so, new stories, which are more than the sum of their individual parts. The Imitation Game (2014) claims to be based on a true story recorded in the seminal biography by Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma (1983). The movie, as does its primary source, endeavours to portray the crucial role of Enigma during World War Two, along with the tragic fate of a key individual, Alan Turing. The film, therefore, involves translation of at least two “true” stories, making the film a rich source of data for this paper that addresses aspects of multimodal inter-semiotic translations (MISTs). Carefully selected aspects of tales based on “true stories” are interpreted in films; however, not all interpretations possess the same degree of integrity in relation to their original source text. This paper assumes films, based on stories, are a form of MIST, whose integrity of translation needs to be assessed. The methodology employed uses a case-study approach and a “grid” framework with two key critical thinking (CT) standards: Accuracy and Significance, as well as a scale (from “low” to “high”). This paper offers a stretched and nuanced understanding of inter-semiotic translation by analysing how multimodal strategies are employed by communication interpretants. Keywords accuracy; critical thinking; inter-semiotic; multimodal; significance; translation; truth 1. -

The Essential Turing Reviewed by Andrew Hodges

Book Review The Essential Turing Reviewed by Andrew Hodges The Essential Turing the Second World War, with particular responsibility A. M. Turing, B. Jack Copeland, ed. for the German Enigma-enciphered naval commu- Oxford University Press, 2004 nications, though this work remained secret until US$29.95, 662 pages the 1970s and only in the 1990s were documents ISBN 0198250800 from the time made public. Many mathematicians would see Turing as a The Essential Turing is a selection of writings of the hero for the 1936 work alone. But he also makes a British mathematician Alan M. Turing (1912–1954). striking exemplar of mathematical achievement in Extended introductions and annotations are added his breadth of attack. He made no distinction be- by the editor, the New Zealand philosopher B. Jack tween “pure” and “applied” and tackled every kind Copeland, and there are some supplementary pa- of problem from group theory to biology, from ar- pers and commentaries by other authors. Alan Tur- guing with Wittgenstein to analysing electronic ing was the founder of the theory of computabil- component characteristics—a strategy diametri- ity, with his paper “On Computable numbers, with cally opposite to today’s narrow research training. an application to the Entscheidungsproblem” (Tur- The fact that few had ever heard of him when he ing 1936). This, a classic breakthrough of twenti- died mysteriously in 1954, and that his work in de- eth century mathematics, was written when he was feating Nazi Germany remained unknown for so twenty-three. In the course of this work in mathe- long, typifies the unsung creative power of math- matical logic, he defined the concept of the uni- ematics which the public—indeed our own stu- versal machine.