An Overview and Analysis of New York's Death Penalty Legislation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hist Oric Black Rock

War of 1812 Bicentennial Community Plan Among Buffalo neighborhoods, in Historic Black Rock you’ll find: • The Best Waterfront Access, • The Best Highway Access, • Historic and Architectural Character, with a War of 1812 Legacy and the Most Pre-Civil War Historic Homes in the city, • Affordable, Quality Housing, and • An Enjoyable, Walkable Waterfront Community The second oldest view of Buffalo (top), according to the Picture Book of Earlier Buffalo, shows the capture of the British brigs Detroit and HISTORIC BLACK ROCK HISTORIC Caledonia on the night of October 8, 1812 during the War of 1812. The Detroit ran aground on Squaw Island (far right), and how the area looks today (bottom). DRAFT DOCUMENT For updates on this planning initiative, visit: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/plan_black_rock/ Draft 12/29/2008 HISTORIC BLACK ROCK: WAR OF 1812 BICENTENNIAL COMMUNITY PLAN DEDICATION This plan is dedicated to all who work tirelessly toward the improvement of Historic Black Rock. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ~ With appreciation to ~ The Honorable Byron Brown, Mayor City of Buffalo Joseph Golombek, Jr., Councilman, North Council District Brian Reilly, Executive Director, Office of Strategic Planning Andrew M. Eszak, City Planner, Office of Strategic Planning Steve Woroniak, CAD Specialist, Office of Strategic Planning Bill Parke, Community Planner, Office of Strategic Planning Co-Chairs Richard Mack and Evelyn Vossler, the Membership, and the Steering Committee of the Black Rock-Riverside Good Neighbors Planning Alliance (BRRGNPA): Sharon Adler Mary Ann Kedron Caleb Basiliko Liza McKee Bill Buzak Bill Parke Beverly Eagen Larry Pernick Jackie Erckert Marge Price Warren Glover Margaret Szcezepaniec Joe Golombek Dearborn Street Community Association Chris Brown, ErieCountyNY1812 Working Group Karl Frizlen, Design Committee, Elmwood Village Association George Grasser, Partners for a Livable Western New York Phil Haberstro, Buffalo Wellness Institute Wende Mix, PhD, Associate Professor of Geography, Buffalo State College Riverside Review St. -

Lessons from New York's Recent Experience with Capital Punishment

BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU ASK FOR: LESSONS FROM NEW YORK’S RECENT EXPERIENCE WITH CAPITAL PUNISHMENT James R. Acker* INTRODUCTION On March 7, 1995, Governor George Pataki signed legislation authorizing the death penalty in New York for first-degree murder,1 representing the State’s first capital punishment law enacted in the post- Furman era.2 By taking this action the governor made good on a pledge that was central to his campaign to unseat Mario Cuomo, a three-term incumbent who, like his predecessor, Hugh Carey, had repeatedly vetoed legislative efforts to resuscitate New York’s death penalty after it had been declared unconstitutional.3 The promised law was greeted with enthusiasm. The audience at the new governor’s inauguration reserved its most spirited 4 ovation for Pataki’s reaffirmation of his support for capital punishment. * Distinguished Teaching Professor, School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany; Ph.D. 1987, University at Albany; J.D. 1976, Duke Law School; B.A. 1972, Indiana University. In the spirit of full disclosure, the author appeared as a witness at one of the public hearings (Jan. 25, 2005) sponsored by the Assembly Committees discussed in this Article. 1. Twelve categories of first-degree murder were made punishable by death under the 1995 legislation, and a thirteenth type (killing in furtherance of an act of terrorism) was added following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. N.Y. PENAL LAW § 125.27 (McKinney 2003). Also detailed were the procedures governing the prosecution’s filing of a notice of intent to seek the death penalty, N.Y. -

Celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month in Buffalo & Erie County

Participating Organizations -Thank you! Hispanic Heritage Council Buffalo Public Schools Upstate New York Transplant Services (UNYTS) Northeast Kidney Foundation El Buen Amigo Celebrating Latin American Cultural Association (LACA) NYS EPIC Eat Smart NY Hispanic Heritage Month in Alianza Latina Kaleida Health Wellcare Buffalo & Erie County Buffalo Prenatal-Perinatal Network Roswell Park Cancer Institute Native American Community Services University at Buffalo Health Sciences Library American Diabetes Association National Grid Sincere thanks to all community organizations, performers, exhibitors; Buffalo & Erie County Public Library and Anne Conable; Historical Society, Museum of Science; Thodore Roosevelt Historical Site; Buffalo Zoo,Buffalo News, WNED TV, Buffalo Rotary, Sam Hoyt (Regional President, Empire State Development Corp.); Tod Kniazuk (Arts Services Initiative WNY); Tom Dee ( Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation ); Steve Stepniak ( City of Buffalo Dept of Public Works ), Buffalo Common Council, Colleges & Universities, for their support! Hispanic Heritage Council of WNY Inc. hispanicheritagewny.org Wilda Ramos, Esmeralda Sierra, Sergio Rodríguez, John Sanabria, September 14, 2012 Tamara Alsace Ph.D., Gilbert Hernández, Miguel Santos, Maritza Vega, Casimiro Rodríguez , Victor Colón de Bonilla, Arnold Zelman - Legal Counsel 12:00 noon Hispanic Heritage Council Salutes Navy Week Buffalo & Erie County Public Library 1 Lafayette Square Buffalo, New York History Hispanic Heritage Month recognizes the contributions of Hispanic Americans in the Program United States and celebrates Hispanic heritage and culture. The observation started in 1968 as Hispanic Heritage Week under President Lyndon Johnson and was expanded Invocation ………………….……..... Msgr. David Gallivan by President Ronald Reagan in 1988 to cover a 30-day period starting on September Pastor, Holy Cross Church 15 and ending on October 15. -

The Park Pioneer Is Published by the Development Office

FALL 2013 Park Pioneer IN THIS ISSUE: Progressive Schools and 21st Century Learning Science and Technology @ Park Herb Mols Honored Proudly Park: Karen Miller and Julian Fraize ’14 Advancement Update Centennial Capital Campaign WWW.thepaRKSCHOOL.ORG PARK LEGACY STUDENTS The Park Pioneer is published by the Development Office Park is proud of our long family history. of The Park School of Buffalo. Please send your comments Legacy students are the children of Park alumni. to [email protected]. FRONT ROW: Mia Koessler, Talia Cerrato, Myles Cerrato, Nadia George, STAFF CONTRIBUTORS Josh Latner, Erik Higgins, Calvin Higgins, Finnegan Cook Christopher J. Lauricella Melissa Baumgart MIDDLE ROW: Head of School Jeremy Besch Chris Wadsworth, Hailey Cerrato, Holly Steveson, Jo Stevens, Summer Harris, Marnie Benatovich Cerrato ’90 Carolyn Hoyt Stevens ’81 Sydney Pfeifer, Connor Levin, Lucas McMahon, Erika Barnes, Cary Killeen Chris Lauricella Director of Development Elizabeth Rakas BACK ROW: Carolyn Hoyt Stevens ’81 Kim Ruppel Oliver Killeen, Brian Halpern, Oliver Powell, Aidan Powell, Flora Kraatz, Valerie Warren Development Associate and Will Derrick, Maggie Parke, Robert Parke, Mia Stevens Annual Fund Coordinator PHOTOGRAPHERS Julie Berrigan Greg Connors Development Associate and Chris Downey Capital Campaign Coordinator Gordon James Photography Teresa Miller Elizabeth Rakas Nancy J. Parisi Communications Coordinator Steve Powell ’81 and Pioneer Editor Elizabeth Rakas Erin Fitzgerald Kim Ruppel Event Coordinator Second Glance Photographers -

Partial Transcript Of: Buffalo and Fort Erie Public Bridge Authority Board Meeting, April 25, 2014 Fort Erie, Ontario (Canada)

2000 P Street NW, Suite 240 Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 265-PEER Fax: (202) 265-4192 [email protected] http://www.peer.org Partial transcript of: Buffalo and Fort Erie Public Bridge Authority Board Meeting, April 25, 2014 Fort Erie, Ontario (Canada) Topic: New York Gateway Connections Improvement Project Duration: 3:21 Start time: 44:39 End time: 48:00 The following is a partial transcript of the April 25, 2014 monthly board meeting of the Buffalo and Fort Erie Public Bridge Authority (PBA) in Fort Erie, Ontario (Canada) regarding matters associated with the New York Gateway Connections Improvement Project of the U.S. Peace Bridge Plaza. The following three individuals can be heard on the recording: Maria Lehman, Project Manager for the New York State Department of Transportation assigned to the New York Gateway Connections Improvement Project Anthony Masiello, PBA Board Member appointed by Governor Andrew Cuomo Sam Hoyt, PBA Board Member appointed by Governor Andrew Cuomo Lehman: I have, as does Sam [Hoyt], the governor’s word that unless we get a restraining order, [the construction contract for the New York Gateway Connections Improvement Project is] gonna get awarded—our intent is—the design is underway now, the final plans are due to be done the end of May [2014], we’re going to be bidding it in late June, and we wanna have a shovel in the ground late September [2014]. So, unless there’s a TRO [Temporary Restraining Order], we’re going. If there’s a TRO, again, we did this Burmese seven-language thing so we could check the box—this was a concern, we handled it, we took care of it. -

Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row

Pace Law Review Volume 22 Issue 2 Spring 2002 Article 3 April 2002 Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row David S. Hammer Art C. Cody Risa B. Gerson Norman L. Greene Michael B. Mushlin Pace University School of Law, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Recommended Citation David S. Hammer, Art C. Cody, Risa B. Gerson, Norman L. Greene, Michael B. Mushlin, and Richard T. Wolf, Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row, 22 Pace L. Rev. 347 (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row Authors David S. Hammer, Art C. Cody, Risa B. Gerson, Norman L. Greene, Michael B. Mushlin, and Richard T. Wolf This article is available in Pace Law Review: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol22/iss2/3 Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row' 1. This article is a report of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and a joint effort of two of the Association's committees, the Committee on Corrections and the Committee on Capital Punishment. The two committees formed a joint subcommittee (hereinafter "the Subcommittee") to undertake this project. -

© 2016 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works. 1 for Educational Use Only

For Educational Use Only People v. Smith, 63 N.Y.2d 41 (1984) 468 N.E.2d 879, 479 N.Y.S.2d 706 case, however, the Court of Appeals should not readily interfere with the verdicts of jurors KeyCite Yellow Flag - Negative Treatment who have had the advantage of seeing and Distinguished by People v. Morgan, N.Y.Co.Ct., June 19, 1998 hearing witnesses. McKinney's Const. Art. 6, 63 N.Y.2d 41 §§ 3, 5. Court of Appeals of New York. 7 Cases that cite this headnote The PEOPLE of the State of New York, Respondent, v. [2] Homicide Lemuel SMITH, Appellant. Miscellaneous particular circumstances July 2, 1984. Direct evidence that bite mark found on victim was made by defendant and other Defendant was convicted in the Supreme Court, Dutchess circumstantial evidence was sufficient to County, Albert M. Rosenblatt, J., of murder while serving sustain defendant's conviction for murder of a life term and was sentenced to death. The Court of a corrections officer. McKinney's Penal Law § Appeals, Kaye, J., held that: (1) evidence was sufficient 125.27. to sustain conviction; (2) expert testimony identifying bite mark found on victim as having been made by defendant Cases that cite this headnote on the basis of comparison with photograph of another bite mark made by defendant on another victim was [3] Criminal Law properly admitted; (3) defendant was not entitled to new Weight and Sufficiency of Evidence trial based on newly discovered evidence; (4) trial judge was not required to recuse himself; but (5) mandatory Testimony of police investigator was sufficient death sentence for homicide committed by person serving to sustain finding that defendant's confession a life term of imprisonment is unconstitutional. -

Assemblymember Sam Hoyt

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Correspondence The Dr. Catherine Collins Collection 2-10-2006 Correspondence; 2006-02-10; Assemblymember Sam Hoyt Catherine Collins Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/collins_correspondence Part of the Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation "Correspondence; 2006-02-10; Assemblymember Sam Hoyt." Correspondence. Monroe Fordham Regional History Center. Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo State. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/collins_correspondence/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Dr. Catherine Collins Collection at Digital Commons at Buffalo State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Correspondence by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ASSEMBLY STATE OF NEW YORK ALBANY CO-CHAIR Task Force on Demographic Research & Reapportionment SAM HOYT Assemblymember 144™ District CO-CHAIR Task Force on High Speed Rail Room 454 Legislative Office Building COMMITTEES Albany, New York 12248 Ways and Means {518) 455-4886 Transportation FAX (518) 455-4890 Energy [email protected] Tourism, Arts & Sports Development Children and Families General Donovan State Office Building 125 Main Street MEMBER Buffalo, New York 14203 Puerto Rican/Hispanic Task Force (716) 852-2795 FAX (716) 852-2799 February 10, 2006 Catherine Collins Roard of Eciucation Room 80 I City Hall Buffalo, NY 14202 Dear Dr. Collins: I am in receipt of the report of the Charter School Moratorium Task Force that you mailed to me on February 3, 2006. -

Viewfromthehill Oct10:Layout 1

A monthly PTSCO publication for the families and staff of City Honors School at Fosdick-Masten Park OCTOBER 2010 Ribbon Cutting Officially Opens the UPCOMING EVENTS New and Improved City Honors School Wednesday, October 6 Early Release Grades 5-8 11:00 AM Grades 9-12 (Metro Bus) Noon Tuesday, October 19 PTSCO Meeting 5:30 PM Saturday, October 23 8:00 - 10:00 AM Senior Breakfast Friday, October 29 6:30 - 8:30 PM “I Scream!” Social for 5th and 6th Graders Saturday, November 6 9:00 AM - Noon Open House for prospective families Saturday, November 6 2:00 - 4:00 PM Mark Goldman, the Citizens for Common Sense & Partners for a Liveable Western NY present Peter Cammarata, Andrea Szalanski, David Cohen, Florence Johnson, Mary Ruth Kapsiak, Lou Petrucci, Imagining Buffalo’s Waterfront See page 8 Jay McCarthy, Dr. James A. Williams, Mayor Byron Brown, and Dr. William A. Kresse at the podium. Wednesday, December 22 Teacher Appreciation Breakfast It was all smiles as the newly renovated City Honors School at Fosdick-Masten Park was officially rededicated with a special assembly and ribbon-cutting ceremony on Monday, September 13. Joining Watch for more info on the the celebration with staff and students were New York State Assemblymen Sam Hoyt, Mayor Byron Winter Bazaar - December 4 Brown, BPS Superintendent Dr. James A. Williams, members of the Buffalo Common Council and Board of Education, past CHS administrators, staff, and parents. A special guest was a 1927 graduate of Fosdick-Masten Park, who was taken on a tour of the building after the festivities. -

Smith, Lemuel

Lemuel Smith Information summarized by Rochelle Thompson, Keith Taylor, Cori Trask, and Brittany Taylor Department of Psychology Radford University Radford, VA 24142-6946 Date Age Life Event 1939 Not born Death of older brother John Jr. Died of encephalitis 07-22-1941 0 Lemuel Smith is born in Amsterdam, NY 1941-1953 Birth to 12 Sleeps in his parents’ bed with his mother while his father is at work 1946 5 Begs John to come back to earth 1947 6 Received second head injury (date of first head injury is unknown) 1947 6 The personality of “Lemo” emerges, according to Eleanor Lee. Summer Receives head injury-fell from a tree while playing Tarzan and was 10 1951 unconscious for several minutes 1951-1958 Adolescence Stalked, kissed, touched, and manually penetrated girls *Receives his fourth head injury while snow sledding 1952-1958 Teenager *Receives his fifth head injury while playing basketball 1953 12 Refuses to attend church with his family 1953 12 The personality of “John” emerges, according to Eleanor Lee December Indicted for burglary of Strech’s coffee shop & Richel’s Confectionary 16 1957 store in Amsterdam New York. 01-21-1958 17 Murder of Dorothy Waterstreet Lemuel was determined to be a suspect in the murder, and was brought in 01-23-1958 17 for questioning. Summer 17 Moved to Schenectady NY to live with his sister Edith 1958 July 1958 17 Edna Johnson beating Summer 17 Has sex with inmate Elliot 1958 01-20-59 17 Trail for the Edna Johnson assault begins 04-12-59 17 Sentenced to maximum of 20 years by Judge Joseph Brynes August 1958- 18-19 In jail at the Baltimore Penitentiary January 1959 1959-1968 17-27 In prison, spends much of his time in solitary confinement 1964 23 1st eligible for parole and is denied Summer *Riot at the prison 23-26 1964-1966 *Eligible for parole 2nd time which is also denied *Against his parents’ wishes, Lemuel converted to Catholicism. -

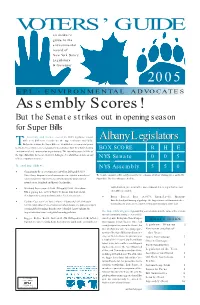

Assembly Scores!

VOTERS’ GUIDE an insider’s guide to the environmental record of New York State’s Legislature & Governor 2005 EPL • ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCATES Assembly Scores! But the Senate strikes out in opening season for Super Bills he Assembly and Senate closed the 2005 legislative session AlbanyAlbany LegislatorsLegislators with very different records on the top environmental bills. T Early in the session, five Super Bills were identified as environmental priori- ties by the Green Panel, a select group of representatives from New York’s leading BOX SCORE R H E environmental and conservation organizations. The Assembly passed all five of the Super Bills while the Senate went 0-5, failing to even allow floor debate on any of these important initiatives. NYS Senate 0 0 5 vs The 2005 Super Bills were: NYS Assembly 5 5 0 Community Preservation Act (A.6450A, DiNapoli/S.3153 Marcellino): Empowers local communities to establish a small real The Senate committed five costly errors for the environment by not allowing votes on the five estate transfer fee with revenues earmarked for the protection of Super Bills. The Assembly passed all five. natural areas, farmland and historic landmarks; bottled waters, juices and other non-carbonated beverages that are not Wetland Protection (A.2048, DiNapoli/S.2081, Marcellino): currently redeemable; Fills a gaping hole in New York’s wetlands laws that allows developers to destroy wetlands under 12.4 acres in size; Burn Barrel Ban (A.3073, Koon/S.2961, Maziarz): Bans the backyard burning of garbage, the largest source of dioxin and other Carbon Cap for New York’s Power Plants (A.4459, DiNapoli/ potentially toxic and cancer-causing chemicals in rural parts of the state. -

Chapter 11 Distribution List

CHAPTER 11 DISTRIBUTION LIST 11.0 DISTRIBUTION LIST The U.S. Department of Energy provided copies of the Final Environmental Impact Statement for Decommissioning and/or Long-Term Stewardship at the West Valley Demonstration Project and Western New York Nuclear Service Center to Federal, State, and local elected and appointed government officials and agencies; American Indian representatives; national, state, and local environmental and public interest groups; and other organizations and individuals as listed. Approximately 200 copies of the complete Final EIS, 1,000 copies of the Summary of the Final EIS, and 700 CDs of the Final EIS were sent to interested parties. Copies will be provided to others on request. United States Congress U.S. Senate The Honorable Robert Bennett, Utah The Honorable Charles E. Schumer, The Honorable Jeff Bingaman, New Mexico New York The Honorable Maria Cantwell, Washington The Honorable Tom Udall, New Mexico The Honorable Saxby Chambliss, Georgia The Honorable Ron Wyden, Oregon The Honorable Jim DeMint, South Carolina Deb Aumick, Senator Catherine Young’s The Honorable John Ensign, Nevada Office The Honorable Kirsten E. Gillibrand, New York Katie Beirne, Legislative Director, Senator The Honorable Lindsey Graham, South Carolina Charles Schumer’s Office The Honorable Orrin Hatch, Utah Polly Trottenburg, Legislative Director, Senator Charles Schumer’s Office The Honorable Johnny Isakson, Georgia Lynn Williams, Regional Representative, The Honorable Jeff Merkley, Oregon Senator Charles Schumer’s Office The Honorable Patty Murray, Washington The Honorable Harry Reid, Nevada U.S. Senate Committees The Honorable Daniel K. Inouye, Chairman, Committee on Appropriations The Honorable Thad Cochran, Ranking Member, Committee on Appropriations The Honorable Byron L.