Lessons from New York's Recent Experience with Capital Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining Turnover in the New York State Legislature: 2009-2010 Update," Feb 2011

A Report of Citizens Union of the City of New York EXAMINING TURNOVER IN THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATURE: 2009 – 2010 Update Research and Policy Analysis by Citizens Union Foundation Written and Published by Citizens Union FEBRUARY 2011 Endorsed By: Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law Common Cause NY League of Women Voters of New York State New York Public Interest Research Group Citizens Union of the City of New York 299 Broadway, Suite 700 New York, NY 10007-1976 phone 212-227-0342 • fax 212-227-0345 • [email protected] • www.citizensunion.org www.gothamgazette.com Peter J.W. Sherwin, Chair • Dick Dadey, Executive Director TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary Page 1 II. Introduction and Methodology Page 3 III. Acknowledgments Page 5 IV. Major Findings on Legislative Turnover, 2009-2010 Page 6 V. Findings on the Causes of Turnover, 1999-2010 Page 8 VI. Opportunities for Reform Page 16 VII. Appendices A. Percentage of Seats Turned Over in the New York State Legislature, 1999-2010 B. Causes of Turnover by Percentage of Total Turnover, 1999-2010 C. Total Causes of Turnover, 1999-2010 D. Ethical and Criminal Issues Resulting in Turnover, 1999-2010 E. Ethical and Criminal Issues Resulting in Turnover Accelerates: Triples in Most Recent 6-Year Period F. Table of Individual Legislators Who Have Left Due to Ethical or Criminal Issues, 1999-2010 G. Table of Causes of Turnover in Individual Assembly and Senate Districts, 2009 – 2010 Citizens Union Examining Legislative Turnover: 2009 - 2010 Update February 2011 Page 1 I. Executive Summary The New York State Legislature looked far different in January 2011 than it did in January 2009, as there were 47 fresh faces out of 212, when the new legislative session began compared to two years ago. -

Where to Find HEOP

Courtesy of the New York State Senate Minority Conference Eric Adams Suzi Oppenheimer Neil D. Breslin George Onorato Martin Connor Kevin S. Parker Ruben Diaz, Sr. Bill Perkins Martin Malavé Dilan John D. Sabini Thomas K. Duane John L. Sampson Efrain González, Jr. Diane J. Savino Ruth Hassell‐Thompson Eric T. Schneiderman Shirley L. Huntley José M. Serrano Jeffrey D. Klein Malcolm A. Smith Craig M. Johnson William T. Stachowski Liz Krueger Toby Ann Stavisky Carl Kruger Andrea Stewart‐Cousins Velmanette Montgomery Antoine M. Thompson David J. Valesky Special Thanks Chloe Mauro Travis Proulx Robert James Bill Short David Bowers Carol Ann Kissam Cheryl N. Williams Carlos Garcia Sylvia R. Carey Sara Morrison Sahiry Rodriguez 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introductory Letter 4 Higher Education Opportunity Program • Program Overview 5 • Funding 7 • Applying to HEOP 7 • Requirements 8 Education Opportunity Program • Program Overview 9 • Funding 10 • Applying to EOP 11 • Requirements 11 SEEK & College Discovery • Program Overview 13 • Funding 13 • Applying to SEEK & College Discovery 14 • Requirements 16 Collegiate Science & Technology Education Program • Program Overview 17 • Funding 17 • Applying to C‐STEP 18 • Requirements 19 General Income Guidelines for All Programs 20 Talk with your Guidance Counselor/Other Resources 21 Contact Information for Universities with Programs 22 3 NEW YORK STATE SENATE MINORITY CONFERENCE Fall 2007 Dear Friend, In todayʹs economy, higher education and life‐long learning have become essential for success. However, the costs of higher education have become unbearable for some, and burdensome for all. According to a recently released study by the U.S. Department of Education, paying for college is a greater burden for New Yorkers than residents of any other state. -

A TIMELINE of AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY in BUFFALO, NY 1790-PRESENT Ince Our Inception, Buffalo Bike Tours Has Sought to Amplify Buffalo’S Lesser Known Histories

CELEBRATE BUFFALO BLACK HISTORY A TIMELINE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY IN BUFFALO, NY 1790-PRESENT ince our inception, Buffalo Bike Tours has sought to amplify Buffalo’s lesser known histories. This February (2021), in light Sof Black History Month and our commitment to the Black Lives Matter movement, we present a series of 4 articles on our city’s black history of resistance and resilience. Want to learn more? Buffalo Bike Tours can provide private tours themed around black history. We are also developing tours for younger audiences. For school field trips on Buffalo black history by bike, bus, or foot, see our website or contact us for more information on hosting your class. BUFFALO BIKE TOURS BUFFALOBIKETOURS.COM [email protected] (716) 328-8432 2 1790-1900 EARLY HISTORY OF BUFFALO’S BLACK COMMUNITY rior to the war of 1812, Buffalo was a pioneer town with a population of just under 1,500. PBuffalo’s first black citizens lived alongside early settlers and largely resided in the Fourth Ward. Buffalo’s black population faced many adversities but experienced more freedom than many other parts of the country. New York State was one of the more liberal states and enacted policies, such as abolishing slavery in 1827. Still, life in Buffalo was far from perfect for black families in the 1800s. Due to its proximity to the Canadian border, Professor Wilbur H. Siebert’s underground railroad of WNY map Buffalo soon became a key part of the underground railroad: it was the last stop before reaching freedom. The city became known to conductors around the country as a network of “stations” were established. -

Award Ceremony November 6, 2013 WELCOME NOTE from RICHARD M

AWARD CEREMONY NOVEMBER 6, 2013 WELCOME NOTE from RICHARD M. ABORN Dear Friends, Welcome to the third annual fundraiser for the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City. This year we celebrate 35 years of effective advocacy – work which has made our city BOARD of DIRECTORS safer and influenced the direction of national, state, and local criminal justice policy. At the Crime Commission, we are prouder than ever of the role we play in the public process. We are also grateful for the generous support of people like you, who make our work possible. CHAIRMAN VICE CHAIRMAN Richard J. Ciecka Gary A. Beller Keeping citizens safe and government responsive requires vigilant research and analysis Mutual of America (Retired) MetLife (Retired) in order to develop smart ideas for improving law enforcement and our criminal justice system. To enable positive change, we are continually looking for new trends in crime and Thomas A. Dunne Lauren Resnick public safety management while staying at the forefront of core issue areas such as guns, Fordham University Baker Hostetler gangs, cyber crime, juvenile justice, policing, and terrorism. Abby Fiorella Lewis Rice This year has been as busy as ever. We’ve stoked important policy discussions, added to MasterCard Worldwide Estée Lauder Companies critical debates, and offered useful ideas for reform. From hosting influential voices in public safety – such as Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman Richard Girgenti J. Brendan Ryan and United States Attorney Preet Bharara – at our Speaker Series forums, to developing KPMG LLP DraftFCB cyber crime education initiatives and insightful research on the city’s gangs, the Crime Commission continued its tradition as the pre-eminent advocate for a safer New York. -

Out of the Abyss of Anger

MENTAL HEALTH NEWSTM YOUR SOURCE OF INFORMATION, EDUCATION, ADVOCACY AND RESOURCES SPRING 2002 FROM THE LOCAL, STATE, AND NATIONAL NEWS SCENE VOL. 4 NO. 2 Out of the Abyss of Anger mor, regulating one’s environ- end up being turned against ment, psychotherapy, medica- themselves in depression, or can tion, etc.). So, you have to be lead to problems with impulse wondering why I am writing control and end up contributing about anger. to legal problems. It seems to me that since Sep- Legal and illegal substances tember 11th, anger, as Emerald are often used to control anger. Lagasse might say, “has been Some people choose opioids as a kicked up a notch.” For the first drug because it helps push away time in all of our lives we have angry feelings, which has re- witnessed terrorism of a monu- sulted in an increase in opioid mental proportion in our own addiction in recent years which backyard. While it is true that may have been further effected we have experienced terrorism in by events of September 11th. Al- our country before, even at the cohol may also suppress and fa- World Trade Center, we have cilitate outbursts of anger, and never seen anything like we have many alcoholics are opioid ad- Anger: The Choice is Yours this past fall. Think of the words Anger: A Candid Discussion dicts as well. Those who are By that have been used since that By addicted to sedative hypnotics date to describe our reactions: are using these drugs as a Richard J. Frances, M.D. -

State Senate District Town/City/Counties NYSNA

NYSNA-Endorsed State Senate District Town/City/Counties Candidates There are no NYSNA-endorsed 1 Brookhaven candidates in this district There are no NYSNA-endorsed 2 East Northport candidates in this district There are no NYSNA-endorsed 3 Suffolk candidates in this district 4 Suffolk Phil Boyle (Rep) 5 Nassau, Suffolk Jim Gaughran (Dem) 6 Nassau County Kevin Thomas (Dem) 7 Nassau County Anna Kaplan (Dem) 8 Seaford John Brooks (Dem) 9 Long Beach, Hempstead Todd Kaminsky (Dem) 10 Queens James Sanders, Jr. (Dem) 11 Queens John Liu (Dem) 12 Queens Michael Gianaris (Dem) 13 Queens Jessica Ramos (Dem) 14 Queens Leroy Comrie (Dem) 15 Queens Joe Addabbo (Dem) 16 Queens Toby Ann Stavisky (Dem) There are no NYSNA-endorsed 17 Kings candidates in this district 18 NYC Julia Salazar (Dem) 19 Kings Roxanne Persaud (Dem) 20 Kings Zellnor Myrie (Dem) 21 Kings Kevin Parker (Dem) 22 Kings Andrew Gounardes (Dem) 23 Kings Diane Savino (Dem) 24 Kings Andrew Lanza (Rep) 25 Kings Velmanette Montgomery (Dem) 26 Kings Brian Kavanagh (Dem) 27 NYC Brad Hoylman (Dem) 28 NYC Liz Krueger (Dem) 29 NYC José M. Serrano (Dem) 30 NYC Brian Benjamin (Dem) 31 Bronx Robert Jackson (Dem) 32 Bronx Luis Sepúlveda (Dem) 33 Bronx Gustavo Rivera (Dem) 34 Bronx Alessandra Biaggi (Dem) Yonkers, Greenburgh, Andrea Stewart-Cousins (Dem) WhIte PlaIns, SCarsdale & 35 New RoChelle 36 Bronx/Mt. Vernon Jamaal Bailey (Dem) 37 Rye City Shelley Mayer (Dem) 38 WestCheter David Carlucci (Dem) 39 Orange/RoCkland/Ulster James Skoufis (Dem) 40 WestCheter Terrence Murphy (Rep) 41 Hyde Park Sue Serino (Rep) 42 Middletown Jen Metzger (Dem) 43 Halfmoon Aaron Gladd (Dem) 44 Albany, Rensselaer Neil Breslin (Dem) ClInton, Essex, FranklIn, There are no NYSNA-endorsed St. -

New York Assembly 145, Mark Schroeder,Democrat 57, Hakeem Jeffries,Democrat 1, Daniel Losquadro,Republican 146, Kevin Smardz,Republican 58, N

Erie Canal 141, Crystal Peoples,Democrat 53, Vito Lopez,Democrat City 142, Jane Corwin,Republican 54, Darryl Towns,Democrat 143, Dennis Gabryszak,Democrat 55, William Boyland,Democrat Mohawk-Erie Corridor Limits 144, Sam Hoyt,Democrat 56, Annette Robinson,Democrat NY Assembly Districts New York Assembly 145, Mark Schroeder,Democrat 57, Hakeem Jeffries,Democrat 1, Daniel Losquadro,Republican 146, Kevin Smardz,Republican 58, N. Nick Perry,Democrat 10, James Conte,Republican 147, Daniel Burling,Republican 59,Alan Maisel,Democrat 100,UNKNOWN AS OF 1/10/11,N/A 148, James Hayes,Republican 6, Philip Ramos,Democrat 101, Kevin Cahill,Democrat 149, Joseph Giglio,Republican 60, Nicole Malliotakis,Republican 102, Joel Miller,Republican 15, Michael Montesano,Republican 61, Mathew Titone,Democrat 103, Marcus Molinaro,Republican 150, Andrew Goodell,Republican 62, Lou Tobacco,Republican 104, John McEneny,Democrat 16, Michelle Schimel,Democrat 63, Michael Cusick,Democrat 105, George Amedore,Republican 114 17, Thomas McKevitt,Republican 64, Sheldon Silver,Democrat 106, Ronald Canestrari,Democrat 18, Earlene Hill Hopper,Democrat 65, Micah Kellner,Democrat 107, Clifford Crouch,Republican 19, David McDonough,Republican 66, Deborah Glick,Democrat 108, Steven McLaughlin,Republican 118 2, Fred Thiele,Democrat 67, Linda Rosenthal,Democrat 109, Robert Reilly,Democrat 20, Harvey Weisenberg,Democrat 68, Robert Rodriguez,Democrat 11, Robert Sweeney,Democrat 122 21, Edward Ra,Republican 69, Daniel O'Donnell,Democrat 110, James Tedisco,Republican 22, Grace Meng,Democrat -

Manhattan Resolution Date

COMMUNITY BOARD 1 – MANHATTAN RESOLUTION DATE: MARCH 23, 2021 COMMITTEE OF ORIGIN: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE VOTE: 11 In Favor 0 Opposed 0 Abstained 0 Recused BOARD VOTE: 39 In Favor 0 Opposed 1 Abstained 0 Recused RE: Strengthening Voting Rights in New York State WHEREAS: A strong democracy depends on consistent and robust participation of eligible voters in every election; and WHEREAS: The New York State Senate passed a comprehensive package of bills to reduce boundaries to voting and create additional protections against voter disenfranchisement; and WHEREAS: All these bills were passed by the Senate, and all but one is waiting on passage in the New York State Assembly; and WHEREAS: State Senate Bill S.264, sponsored by Senator Zellnor Myrie, sets deadline for absentee ballot applications sent by mail to 15 days before the election, up from 7 days, to better allow for voters timely receiving their absentee ballot; and WHEREAS: State Senate Bill S.360, sponsored by Senator Leroy Comrie, amends the State Constitution to allow for any voter to vote by absentee without an excuse; and WHEREAS: State Senate Bill S.631, sponsored by Senator Julia Salazar, permits Boards of Elections to receive absentee ballot applications earlier than thirty days before the applicable Election Day by making permanent Chapter 138 of the Laws of 2020, which sunset on December 31, 2020; and WHEREAS: State Senate Bill S.516, sponsored by Deputy Majority Leader Michael Gianaris, establishes a mandatory timeframe for processing of absentee ballot applications and ballots by Boards of Elections based on when the application was received; and WHEREAS: State Senate Bill S.632, sponsored by Senator Robert Jackson, permanently allows voters to apply for absentee ballots online and allows absentee ballots postmarked through Election Day by making permanent Chapter 91 of the Laws of 2020, which sunset on December 31, 2020. -

Final QCAP Media Advisory 7.14.031

A collaborative of: Natural Resources Defense Council New York Power Authority New York Public Interest Research Group New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Northeast States Clean Air Foundation/ Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management Queens Borough President’s Office Queens Clean Air Project Contacts: Cindy Drucker, NESCAF/CAC, (617) 367-8540 Glenn Goldstein, NESCAF/CAC, (631) 472-0011 Luis Rodriguez, NYPA, (718) 626-8239 MEDIA ADVISORY NEW QUEENS CLEAN AIR PROJECT WILL AWARD $2 MILLION TO COMMUNITY GROUPS FOR LOCAL CLEAN AIR & ENERGY INITIATIVES WHAT: Clean Air Communities announces a new partnership that will provide $2 million in direct funding to implement clean air and energy efficiency projects in Northwest Queens neighborhoods. Funded by the New York Power Authority (NYPA), this innovative project will sponsor community-based emissions reductions and renewable and alternative energy projects to deliver air quality, public health, and other community benefits in Queens. WHO: · The Honorable Helen Marshall, President, Borough of Queens · The Honorable George Onorato, Senator, New York State Senate · The Honorable Peter Vallone, Jr., Council Member, New York City Council · The Honorable Michael Gianaris, Assembly Member, New York State Assembly (Invited) · Eugene Zeltmann, President and Chief Executive Officer, New York Power Authority · Ken Colburn, Executive Director, Northeast States Clean Air Foundation and Clean Air Communities · Ashok Gupta, Director – Air and Energy Programs, Natural Resources Defense Council · Lisa Garcia, Lead Attorney, New York Public Interest Research Group WHEN: TUESDAY, JULY 15th 12:00 – 1:00 Press event, including formal remarks and Q & A. 1:00 – 2:00 Luncheon. Tour of NYPA’s new state-of-the-art generating facility available. -

Voters' Guide

VOTERS’ GUIDE an insider’s guide2006 to the environmental records of New York State lawmakers EPL•Environmental Advocates EPL/Environmental Advocates EPL/Environmental Advocates was one of the first organizations in Board of Directors the nation formed to advocate for the Irvine Flinn, President future of a state’s environment and Laura Haight, Vice President the health of its citizens. Through Cara Lee, Secretary & Treasurer lobbying, advocacy, coalition Richard Allen building, citizen education and policy Richard Booth development, EPL/Environmental Eric A. Goldstein Lee Wasserman Advocates has been New York’s environmental conscience for Robert Moore, Executive Director almost 40 years. We work to ensure environmental laws are enforced, that tough new measures are enacted, and EPL/Environmental Advocates 353 Hamilton Street that the public is informed of, and Albany, NY 12210 participates in, important policy 518.462.5526 debates. EPL/Environmental www.eplvotersguide.org Advocates is a nonprofit corporation tax exempt under section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code. TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 LEGISLATIVE WRAP-UP 09 BILL SUMMARIES HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 14 ASSEMBLY SCORES 04 NEW LAWS 20 SENATE SCORES 05 BY THE NUMBERS 21 HOW SCORES ARE CALCULATED 06 PATAKI RETROSPECTIVE 22 WHAT YOU CAN DO 07 AWARDS 08 NYS BUDGET KILLED BILLS EPL•Environmental Advocates LEGISLATIVE WRAP-UP Big Bucks for the Environment, While State Senate Stymies Super Bill Success While the Governor and Legislature increased floor vote on a single Super Bill, despite the Environmental Protection Fund to $225 unprecedented bipartisan support in that house. million this year—no small feat—the State Senate made certain little else was But that’s how things work in Albany. -

Autumn 2004 ✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩ Election ‘04 ✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩✩ Editorials What’S at Stake on Nov

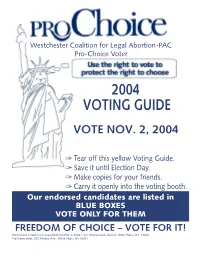

Westchester Coalition for Legal Abortion-PAC Pro-Choice Voter 2004 VOTING GUIDE VOTE NOV. 2, 2004 ✑ Tear off this yellow Voting Guide. ✑ Save it until Election Day. ✑ Make copies for your friends. ✑ Carry it openly into the voting booth. Our endorsed candidates are listed in BLUE BOXES VOTE ONLY FOR THEM FREEDOM OF CHOICE – VOTE FOR IT! Westchester Coalition for Legal Abortion-PAC © 2004 • 237 Mamaroneck Avenue, White Plains, NY 10605 ProChoice Voter, 300 Martine Ave., White Plains, NY 10601 Please copy and distribute this page to other pro-choice Westchester County Voters. 2004 Voting Guide WCLA Endorsement Policy, 2004 WCLAʼs endorsements are determined case by case. To be considered for endorsement, candidates must return WCLAʼs questionnaire and participate in an interview if requested Westchester Coalition for Legal Abortion-PAC by WCLA. ProChoice Voter Incumbents shall be endorsed over pro-choice challengers if they have consistent vot- ing records and have established a reputation for strong leadership and extra effort in advancing access to abortion and contraception. Non-incumbents will be endorsed if they Candidates endorsed by WCLA are have demonstrated leadership in the community on the issue. To be considered for endorsement, candidates must unequivocally support: highlighted in boxes. Help keep • access to abortion and contraception for all women, unimpeded by laws, restrictions, or regulations; abortion legal and accessible. • strict confidentiality for all reproductive health care; Vote for endorsed candidates. • coverage by public and private insurance of abortion and contraception. Judicial candidates: To be eligible for endorsement, judicial candidates must participate in an interview if requested by WCLA, and neither seek nor accept the Right to Life Party nomination. -

Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row

Pace Law Review Volume 22 Issue 2 Spring 2002 Article 3 April 2002 Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row David S. Hammer Art C. Cody Risa B. Gerson Norman L. Greene Michael B. Mushlin Pace University School of Law, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Recommended Citation David S. Hammer, Art C. Cody, Risa B. Gerson, Norman L. Greene, Michael B. Mushlin, and Richard T. Wolf, Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row, 22 Pace L. Rev. 347 (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row Authors David S. Hammer, Art C. Cody, Risa B. Gerson, Norman L. Greene, Michael B. Mushlin, and Richard T. Wolf This article is available in Pace Law Review: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol22/iss2/3 Dying Twice: Conditions on New York's Death Row' 1. This article is a report of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and a joint effort of two of the Association's committees, the Committee on Corrections and the Committee on Capital Punishment. The two committees formed a joint subcommittee (hereinafter "the Subcommittee") to undertake this project.