Battlefield Banaras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-SA 4.0 © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847108627 – ISBN E-Lib: 9783737008624 Wiener Forumfür Theologieund Religionswissenschaft/ Vienna Forum for Theology and the Study of Religions Band 16 Herausgegeben im Auftrag der Evangelisch-Theologischen Fakultät der Universität Wien, der Katholisch-Theologischen Fakultät der Universität Wien und demInstitutfür Islamisch-Theologische Studiender Universität Wien vonEdnan Aslan, Karl Baier und Christian Danz Die Bände dieser Reihe sind peer-reviewed. Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-SA 4.0 © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847108627 – ISBN E-Lib: 9783737008624 Karl Baier /Philipp A. Maas / Karin Preisendanz (eds.) Yoga in Transformation Historical and Contemporary Perspectives With 55 figures V&Runipress Vienna University Press Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-SA 4.0 © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847108627 – ISBN E-Lib: 9783737008624 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISSN 2197-0718 ISBN 978-3-7370-0862-4 Weitere Ausgaben und Online-Angebote sind erhältlich unter: www.v-r.de Veröffentlichungen der Vienna University Press erscheinen im Verlag V&R unipress GmbH. Published with the support of the Rectorate of the University of Vienna, the Association Monégasque pour la Recherche Académique sur le Yoga (AMRAY) and the European Research Council (ERC). © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Robert-Bosch-Breite 6, D-37079 Göttingen / www.v-r.de Dieses Werk ist als Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der Creative-Commons-Lizenz BY-SA International 4.0 (¹Namensnennung ± Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungenª) unter dem DOI 10.14220/9783737008624 abzurufen. -

Place-Making in Late 19Th And

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts TERRITORIAL SELF-FASHIONING: PLACE-MAKING IN LATE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURY COLONIAL INDIA A Dissertation in History by Aryendra Chakravartty © 2013 Aryendra Chakravartty Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 The dissertation of Aryendra Chakravartty was reviewed and approved* by the following: David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Director of Graduate Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Joan B. Landes Ferree Professor of Early Modern History & Women’s Studies Michael Kulikowski Professor of History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Head, Department of History Madhuri Desai Associate Professor of Art History and Asian Studies Mrinalini Sinha Alice Freeman Palmer Professor of History Special Member University of Michigan, Ann Arbor * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract My project, Territorial Self-Fashioning: “Place-Making” in Late 19th and Early 20th Century Colonial India, focuses on the province of Bihar and the emergence of a specifically place-based Bihari regional identity. For the provincial literati, emphasizing Bihar as an “organic” entity cultivated a sense of common belonging that was remarkably novel for the period, particularly because it implied that an administrative region had transformed into a cohesive cultural unit. The transformation is particularly revealing because the claims to a “natural” Bihar was not based upon a distinctive language, ethnicity or religion. Instead this regional assertion was partially instigated by British colonial politics and in part shaped by an emergent Indian national imagination. The emergence of a place-based Bihari identity therefore can only be explained by situating it in the context of 19th century colonial politics and nationalist sentiments. -

The Kolkata Municipal Corporation Advertisement Department Borough/Ward Wise Hoarding List

The Kolkata Municipal Corporation Advertisement Department Borough/Ward Wise Hoarding List Unit Type: Non LUC Paying Unit Unit Sub Type: Private Hoarding Sl. No Br Ward Premises Name of Street Location Unit Code. Size No (SqFt) 1 1 001 56 COSSIPORE ROAD COSSIPORE RD. 08-01-001-003-0001 90 2 1 001 56 COSSIPORE ROAD COSSIPORE RD. 08-01-001-003-0002 200 3 1 001 56 COSSIPORE ROAD COSSIPORE RD. 08-01-001-003-0003 200 4 1 001 BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD SINTHEE MORE 08-01-001-001-0025 200 5 1 001 BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD CROSSING OF B T ROAD/ D 02-01-001-001-0026 200 D ROAD 6 1 001 72 BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD B.T. RD. 08-01-001-001-0002 200 7 1 001 47A BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD B.T.ROAD 08-01-001-001-0001 144 8 1 001 BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD BARACKPORE BRIDGE 08-01-001-001-0022 200 9 1 001 BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD BARACKPORE BRIDGE 08-01-001-001-0023 300 10 1 001 BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD BARACKPORE BRIDGE 08-01-001-001-0024 300 11 1 001 BARRACKPORE TRUNK ROAD B.T.RD. 08-01-001-001-0021 450 12 1 002 7/14A DUM DUM ROAD DUM DUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0003 300 13 1 002 7/14A DUM DUM ROAD DUM DUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0004 288 14 1 002 7/14A DUM DUM ROAD DUMDUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0005 200 15 1 002 7/14A DUM DUM ROAD DUM DUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0006 200 16 1 002 7/14A DUM DUM ROAD DUMDUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0007 300 17 1 002 11/2C DUM DUM ROAD DUM DUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0001 200 18 1 002 11/2C DUM DUM ROAD DUM DUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0002 200 19 1 002 14V DUM DUM ROAD DUM DUM ROAD 08-01-002-004-0008 64 20 1 002 BARRACPORE TRUNK ROAD NEAR CHIRIAMORE BSNLST 02-01-002-001-0001 -

Author Name Name of the Book Book Link Sub-Section Uploader ? A

Watermark Author Name Name of the Book Book Link Sub-Section Uploader ? A http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/15177-bidesher-nisiddho- Bidesher Nisiddho Uponyas (3 volumes) uponyas-3-volumes/ Anubad Peter NO http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abadhut Fokkod Tantram php/topic/12191-fokkodtantramrare-book/ Exclusive Books & Others মানাই http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abadhut Morutirtho Hinglaj php/topic/9251-morutirtho-hinglaj-obodhut/ Others Professor Hijibijbij http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/3987-a-rare-poem-by- Abanindranath Thakur A rare poem by Abaneendranath Tagore abaneendranath-tagore/ Kobita SatyaPriya http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abanindranath Thakur rachonaboli - Part 1 & php/topic/5937-abanindranath-thakur- Abanindranath Thakur 2 rachonaboli/ Rachanaboli dbdebjyoti1 http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/12517-alor-fulki-by- Abanindranath Thakur Alor Fulki abanindranath-thakur/ Uponyas anku http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/12517-alor-fulki-by- Abanindranath Thakur Alor Fulki abanindranath-thakur/ Uponash Anku No http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/5840-buro-angla-by- abanindranath-thakur-bd-exclusive-links- Abanindranath Thakur Buro Angla added/ Uponash dbdebjyoti1 YES http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/14636-choiton-chutki- abanindranath-thakur-53-pages-134-mb- Abanindranath Thakur Choiton Chutki pdf-arb/ Choto Golpo ARB NO http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abanindranath Thakur Khirer Putul php/topic/6382-khirer-putul/ Uponash Gyandarsi http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/6379-pothe-bipothe- কঙ্কালিমাস Abanindranath Thakur Pothe Bipothe abanindranath-thakur/ Uponyas করোটিভূষণ http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/5937-abanindranath-thakur- Abanindranath Thakur Rachonaboli rachonaboli/ Rachanaboli dbdebjyoti1 http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/6230-shakuntala-abanindranath- Abanindranath Thakur Shakuntala tagore/ Choto Golpo Huloo Don http://bengalidownload.com/index. -

Professor KAZI DIN MUHAMMAD (B

http://www.bmri.org.uk Professor KAZI DIN MUHAMMAD (b. 1927- d. 2011) I have been aware of Kazi Din Muhammad since my youth. I first became familiar with his name as early as 1958 when I read a book of humorous anecdotes titled “Golak Chandrer Antmakatha” (Autobiography of Golak Chandra). As a young student, I found the book very funny and hilarious. The author of this book was born in the district Faridpur (circa 1906), but many years later when I asked Dr Kazi Din Muhammad whether he was the author of that book, he revealed that it was, in fact, written by another Kazi Din Muhammad who was also a prominent writer. Long time after I left Alokdihi Jan Bakhsh High English School in Dinajpur, I heard Kazi Din Muhammad’s name again, thanks to late Professor Mufakhkharul Islam, who taught Bengali Literature at Carmichael College, Rangpur. He told me that he was a classmate of Kazi Din Muhammad in the Department of Bangla at Dhaka University in the late 1940s. He remembered him affectionately, as both of them had studied for their Master’s Degree (MA) in Bengali Literature at Dhaka University in 1949. When the Examination results were published, Kazi Din Muhammad was awarded First Class First Degree and Mufakhkharul Islam had received a Second Class First. They remained good friends and held each other in high regard. In fact, both of them became very prominent scholars of Bengali Literature. When I had an opportunity to speak to Professor Kazi Din Muhammad in 2006, he confirmed that he was indeed a classmate of Mufakhkharul Islam at Dhaka University. -

JOURNAL of the ASIATIC SOCIETY of ·BOMBAY (New Series)

VOLUME 33 1958 JOURNAL OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY OF ·BOMBAY (New Series) Edited py P. V. KANE H.D.VELANKAR J.M. UNVALA G. C. JHALA Managing Editor GEORGE M. MORAES C 0 N T EN T S : Page S. P. TOL&:TOV : Results of the work of the Khoresmian Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition of the USSR Academy of Sciences-191H-56 1 H. D. VELANI-$'.AR : Vrttarainii.kara-tiitparya-t1ka of TrivilU"ama : Intro- duction 25 B. G. GOKHALE : Bombay and ~hivaji 69 H. S. URSEKAR : The Moon in the I;tgveda 80 .M. K. DHAVLIKAR : Identification· of the Musikanagara 97 S. L. MALURKAR: Determination of seasons and equinoxes in old India and related festivals ·· 101 . N. G. CHAPEK!AR: Subandhu and Asamati 106 K. H. V. SARMA : Note on Ivlelpadi Inscription of Krishi;iadevarii.ya 112 V. S. PATHAK : Vows and Festivals in Early Medieval Inscriptions of Northern India 116 S. L. MALHOTRA : Commercial Rivalry in the Indian Ocean in Ancient Tim~ 1~ NOTES AND QUERIES : P. V. KANE: Date of Utpala 147 REVIEWS OF BOOKS : Der J;tgveda (H. D. Velankar); The Subh~ita Ratnako.~a (H. D. Velankar) ; Chcindogya-Brcihma1.i.am (H. D. Velankar) ; Kadambari: A Cultural Stud11 (H. D. Velankar) ; Development of Hindu Iconography (A. D. Pusalkar); The Evolution of Man (H. D. Sankalia); A Source Book in Indian Philosophy (A. D. Pusalkar); On the Meaning of the Mq.habhtirata (S. S. Bhawe); The Inda-Greeks (P. C. Divanji); Grammar of the Marathi Language (R. K. Lagu); The Pre historic Baclcg1·ound of Indian· Culture (A. -

PROCEEDINGS of the ASIATIC SOCIETY of BENGAL SDITED by the Honorary Jsecretary

: PROCEEDINGS OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETY OF BENGAL. EDITED BT The tfoNoi\AE\Y jSecf^tae\y, JANUARY TO DECEMBER, 1900. rv CALCUTTA 0^ PRINTED AT THE BAPTIST MISSION PRESS, \^ AND PUBLISHED BY THE ASIATIC SOCIETY, 57, PARK STREET. 1901. CONTENTS. Pages. Proceedings for January, 1900 ... ... ^^ -,_g Ditto „ February (including „ Annual Report) ... 9-66 Ditto „ March „ ... .., .,^ "' g^ Ditto April „ „ ... _ 753^ Ditto May & June, „ 1900 ... gl_gg Di to „ Au t „ ... 99-102 -Uitto October „ and November, 1900 ... "'... 103-106 Ditto December, „ 1900 ... ... 107-111 List of Members of the Asiatic Society on the 31st Decem- ber, 1899 (Appendix to the Proceedings for February^' 1900) ... ... ^^^ i-xiv Abstract Statement of Receipts and Disbursements of the Asiatic Society for the year 1899 (Appendix to the Pro- ceedings for February, 1900) xv~xxiii List of all Societies, Institutions, &c., to which the publi- cations of the Asiatic Society have been sent during the year, or from which publications have been received xxiv-xxx J California Academy of Sciences Presented by .A s i atic HocJety o f Bengal. 1907_. Apri l . 2_ _, PROCEEDINGS OF THI ASIATIC SOCIETY OF BENGAL For January, 1900, The Monthly General Meeting of the Society, was held on Wednesday, the 3rd January, 1900, at 9 p.m. T. H. Holland, Esq., F.G.S., A R C.S., in the chair. The following members were present : — Major A. Alcock, I.M.S., Mr. J. Bathgate, Mr. H. Beveridgc, Dr. T. Bloch, Babu Nobinchand Bural, Mr. W, K. Dods, Mr. F. Finn, Mr. D. Hooper, Mr. G, W. Kiichler, Dr. -

2. Shanker Thapa Ph.D., Buddhist Sanskrit Literature of Nepal, Seoul: Minjoksa Publishing Company 2005, 194 Pp

2. Shanker Thapa Ph.D., Buddhist Sanskrit Literature of Nepal, Seoul: Minjoksa Publishing Company 2005, 194 pp. Appendices, Bibliography, Index, Soft cover, Price. US $ 15. Buddhism is very rich for its numerous literatures. Mahayana/Vajrayana literature is written in Sanskrit. Later on, these texts have been translated into Tibetan and Chinese languages also. But, compared to the Hindu texts, Buddhist literature is not so much exposed to the general readers. Only few of them have come in print, and the huge portion of it still exists in the form of manuscripts. Among the numerous Buddhist literature, Nepal is the abode of Sanskrit literature, and in the words of Dr. Rajendra Ram, Nepal is the 'Custodian of the Buddhist scriptures.' Shanker Thapa's book on this important aspect of Nepalese Buddhism gives us a descriptive and analytical view of the Buddhist Sanskrit literature in Nepal. The author, a Ph.D. agrarian history of Nepal has published two books relevant to his research, but after that he switched on to Buddhism and published four books on Nepalese Buddhism within few months in 2005, perhaps a record for a Nepalese scholar. Among them, two are on Newar Buddhism, one on an old Buddhist monastery, ratnakar Mahavihara and the last one is on Buddhist Sanskrit literature of Nepal, which is going to be reviewed here. Divided into five chapters, the book gives us the historical context of Buddhist Sanskrit literature of Nepal and their nature, contributions of different scholars mainly foreign in disseminating these manuscripts in different countries, notably England, and an overview of the catalogues of manuscripts in Nepal and abroad. -

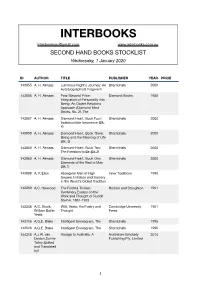

Second Hand Jan 2020

INTERBOOKS [email protected] www.interbooks.com.au SECOND HAND BOOKS STOCKLIST Wednesday, 1 January 2020 ID AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE 143055 A. H. Almaas Luminous Night's Journey: An Shambhala 2000 Autobiographical Fragment 143056 A. H. Almaas Pearl Beyond Price: Diamond Books 1988 Integration of Personality into Being: An Object Relations Approach (Diamond Mind Series, No. 2), The 143057 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Four: Shambhala 2000 Indestructible Innocence (Bk. 4) 143058 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Three: Shambhala 2000 Being and the Meaning of Life (Bk. 3) 143059 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book Two: Shambhala 2000 The Freedom to Be (Bk.2) 143060 A. H. Almaas Diamond Heart, Book One: Shambhala 2000 Elements of the Real in Man (Bk.1) 143088 A. P. Elkin Aboriginal Men of High Inner Traditions 1993 Degree: Initiation and Sorcery in the World's Oldest Tradition 143359 A.C. Harwood The Faithful Thinker: Hodder and Stoughton 1961 Centenary Essays on the Work and Thought of Rudolf Steiner, 1861-1925 143348 A.G. Stock, W.B. Yeats: His Poetry and Cambridge University 1961 William Butler Thought Press Yeats 143116 A.G.E. Blake Intelligent Enneagram, The Shambhala 1996 143516 A.G.E. Blake Intelligent Enneagram, The Shambhala 1996 144318 A.J.W. van Voyage to Australia, A Australian Scholarly 2014 Delden,Dorine Publishing Pty, Limited Tolley (Edited and Translated by) !1 ID AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE 144236 A.L. Where Is Bernardino? Two Rivers Press 1982 Staveley,Nonny Hogrogian 143361 A.L. Stavely Themes: I Two Rivers Press 143362 A.L. -

The Acceptance of Mlearning Amongst the Suburban College Students

International Journal of English Learning and Teaching Skills; Vol. 3, No. 2; Jan 2021, ISSN: 2639-7412 (Print) ISSN: 2638-5546 (Online) Running Head: THE ACCEPTANCE of mLEARNING AMONGST THE SUBURBAN COLLEGE STUDENTS 1 The acceptance of mLearning amongst the suburban college students: A micro-level study in North 24 Pargana of West Bengal Indrani Sarkar (Ph.D. Research Scholar) Department of Journalism and Mass Communication of Calcutta University of Calcutta 1976 International Journal of English Learning and Teaching Skills; Vol. 3, No. 2; Jan 2021, ISSN: 2639-7412 (Print) ISSN: 2638-5546 (Online) Running Head: THE ACCEPTANCE of mLEARNING AMONGST THE SUBURBAN COLLEGE STUDENTS 2 Abstract The revolution of mobile phones is not merely limited to calling or texting; it has reached almost every sphere of humankind. In this 21st century, studies have claimed that mobile phones' accessibility is comparatively higher than the toilet. Nearly 6 billion people worldwide now are accessing a working mobile handset (UNESCO, 2014). The ubiquitous use of mobile phones brings mobility to its users and helps them accept this ICT based technology worldwide. This new technology of communication also has a remarkable contribution to the educational sector. Its real-time communication makes learning effortless and congenial to the potential learners. This study will explore mobile-based learning technology among the higher education aspirants of suburban colleges in North 24parganas of West Bengal. Suburban students are not getting the same facilitates as metro city students. Besides that, suburban culture and social taboos sometimes make problems to use or access mobile phones by students. However, this will not be focused on the comparison between metro city students and suburban students. -

Sirjanã a Journal on Arts and Art Education Vol

1 5 th Anniversary SIRJANÃ A Journal on Arts and Art Education Vol. 3, 2016 The 15th Anniversary Special Chief Editor | Krishna Manadhar Executive Editor | Navindra Man Rajbhandari Consultant Editors| Madan Chitrakar, Jitendra Man Rajbhandari Design | Bijaya Maharjan Production Support | Gautam Manandhar, Bandana Manandhar, Bhawana Sharma Photograph Contribution | Laxman Bhujel, Rabin Kaji Shakya Cover Image |Jerom Maharjan, BFA 2nd Year (Makar, Plaster of Paris, 2016) Printing | Prism Color Scanning and Press Support, Kuleshwor, Kathmandu, 01 428 2511 Published by SIRJANA COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Utter Dhoka Sadak, Lazimpat, Kathmandu, Nepal 01 441 2634, 01 441 8455 www.sirjanacollege.edu.np [email protected] Established in 2001 in affiliation to Tribhuvan University The opinions and the interpretations expressed in the articles are the personal views of authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher and editors. 1 5 th Anniversary editorial Art is the aesthetic tool for expressing human feelings, emotions and perceptions. Art brings beauty into our world. And beauty brings joy in our lives. Art immortalizes people, places and events. Art helps us to organize the world and serves as an important intellectual stimulant. From the very first day of the inception of SIRJANA COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS, it has been the prime mission of the college to establish the value of art in the Nepali society. The college has dedicated itself in an effort of making people understand the society, the culture and the world through academic interactions among students, teachers and artists. Today Sirjana College of Fine Arts is celebrating its 15th Anniversary. For an educational institution the period of fifteen years may not be too long time but when we look back to these years, we feel proud of our achievements and contribution as the sole art institution run by the community. -

安貝卡與其新佛教運動之研究A Study on BR

南 華 大 學 宗 教 學 研 究 所 碩 士 論 文 題目:安貝卡與其新佛教運動之研究 A Study on B.R. Ambedkar and His Neo-Buddhist Movement 指導教授: 黃柏棋 博士 何建興 博士 研 究 生:釋覺亞(周秀真) 中華民國 96 年 6 月 1 日 論 文 摘 要 本文主要探討印度獨立後,第一任法務部長安貝卡(B.R. Ambedkar,1891-1956 A.D.)於 1956 年號召五十萬賤民改變信仰皈依佛教之新佛教運動的始末與蘊含之 意義。 由於印度教種姓制度與印度社會緊密結合,二千多年來印度賤民為了贖罪的理 由,不得不恪守印度教《摩奴法典》給予的誡命,遵行加諸於賤民的種種剝削。由 於西方民主政治思想的影響,印度種姓制度下傳統的生活型態、職業限制、階級人 權的合理性,都受到直接的衝擊。安貝卡即是把握這個歷史時間點,藉由社會抗爭、 政治立法到皈依佛教的改革途徑,將民主政治的自由、平等、博愛與佛教「眾生平 等」思想結合,爭取賤民的基本人權,並以宗教彌補政治無法達致的心理層面,幫 助賤民從內心移除生而卑賤的種姓思想。安貝卡的新佛教運動,不只是復興印度佛 教,也可視為是爭取人權的解放運動。 本文首先舖陳近代印度社會、政治、宗教的概況,以作為新佛教運動的時代背 景,其次由安貝卡的生平及思想,了解新佛教運動思想的來源及發展過程,並透過 解析斯里蘭卡佛教及印度佛教的復興,以及安貝卡對印度各大宗教的觀點,來探討 他帶領賤民皈依佛教的遠因及關鍵時機。最後則以人間佛教的觀念,來省察安貝卡 社會改革的作法,佛教思想所蘊含的自由、平等概念為何,以及對安貝卡復興印度 佛教的具體作法提出個人看法。 關鍵字:安貝卡、印度佛教、賤民、種姓、人間佛教 Abstract This thesis explores Neo-Buddhist Movement and its implications regarding conversions by the five hundred thousand Untouchables to Buddhism in 1956 when India gained its independence from Britain. The paper traces the historical background of the movement and puts the figure, B.R. Ambedkar, as the focus. B.R. Ambedkar was the first Law Minister of the Nehru Cabinet, who organized the Neo-Buddhist movement and contributed to the large-scale conversion movement. The context of the movement is embedded in Hindu caste system, with which the Indian society has been rigidly bound for more than two thousand years. Under the caste system, the Untouchables had to abide to the restrictions specified in the Hindu scripture “Manusmruti”, and suffered from social segregation and exploitation merely for the redemption of their inherent sins. However, the Indian society has been greatly influenced by contemporary ideas in Western democracy.