Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

Sakti Consciousness in Tantra

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Sakti Consciousness in Tantra Himanshu Sekhar Bhuyan There are eight great Sakti pithas in the land of Ugratara of Bhusandapur, Daskhinakali of Lord Jagannath surrounding Srikshetra such as; Harekrisnapur, Narayani of Barakul etc. - Bimala in Puri, Mangala in Kakatapur, Bhagabati Out of general evidences, it might be in Banapur, Charchika in Banki , Biraja in Jajpur, mentioned here that most Chandi Pithas are being Sarala in Jhankad, Bhattarika in Badamba, placed in four corners such as- Samaleswari in Cuttack Chandi in Cuttack. Apart from these Sambalpur, Tarini in Keonjhar, Tara in Ganjam prominent eight Sakti Pithas, there are many and Ambika in Baripada. Out of many expressive Chandi Pithas in different places of Odisha. There figures of Sakti, a few goddesses are having are thirty four Sakti Pithas and nineteen Saiva terrible postures like Chandi, Chinnamasta, Pithas, which are surrounded by sixteen Chamunda are related to tantric rituals. Many Mahasakti Pithas for the sake of their sacred spheres of divine goddesses still remain preservation. unworshipped. All of those are based on sound The other ‘Sakti’s names of Divine foundation of Tantra and most of those are out of Mother are as such; — Baseli of common views. Choudwar,‘Barunei’ of Khorda, Gouri of A few aspects are seemed to be the same Bhubaneswar, Bhadrakali of Bhadrak, Bhairavi in ‘Agama’. The ‘jyotisha’ or‘jyotisha tatwa’, seen of Boud, Hingulai of Talcher, Budhi Thakurani of in the scriptures of ‘tantra’ as well as ‘yamala’ of Angul, Sidhakali of Keonjhar, Bindhyabasini of ‘AGAMA’, although appear to be almost same, Redhakhol, Ghanteswari of Chipilima, it varies from its ways of appliances. -

Die Wurzeln Des Yoga Haṭha Yoga Teil 2

Die Wurzeln des Yoga Haṭha Yoga Teil 2 as tun wir eigentlich, wenn wir Âsanas üben? WWie begründen wir, dass die Praxis einer bestimmten Haltung Sinn macht? Worauf können wir uns stützen, wenn wir nach guten Gründen für das Üben eines Âsanas suchen? Der Blick auf die vielen Publikationen über Yoga zeigt: Bei den Antworten auf solche Fragen spielt – neben dem heutigen wissenschaftlichen Kenntnisstand – der Bezug auf die lange Tradition des Yoga immer eine wichtige Rolle. Aber sind die Antworten, die uns die alten mündlichen und schriftlichen Traditionen vermitteln, befriedigend, wenn wir nach dem Sinn eines Âsanas suchen? Was können wir von der Tradition wirklich lernen und was eher nicht? Eine transparente und nachvollziehbare Erklärung und Begründung von Yogapraxis braucht eine ernsthafte Reflexion dieser Fragen. Dafür ist ein auf Fakten gründender, ehrlicher und wertschätzender Umgang mit der Tradition des Ha†hayoga unverzichtbar. Dabei gibt es einiges zu beachten: Der physische Teil des Ha†hayoga beinhaltet keinen ausgewiesenen und fest 6 VIVEKA 57 Die Wurzeln des Yoga umrissenen Kanon bestimmter Âsanas, auch wenn bis heute immer wieder von „klassischen Âsanas“ die Rede ist. Auch gibt es kein einheitliches und fest umrissenes Konzept, auf das sich die damalige Âsanapraxis stützte. Vielmehr zeigt sich der Ha†hayoga als Meister der Integration verschiedenster Einflüsse und ständiger Entwicklung und Veränderung. Das gilt für die Erfindung neuer Übungen mit ihren erwarteten Wirkungen wie auch für die großen Ziele der Yogapraxis überhaupt. Um die Tradition des Ha†hayoga zu verstehen reicht es nicht, einen alten Text nur zu zitieren. Es bedarf vielmehr eines Blickes auf seine Entwicklung und Geschichte. -

9789004400139 Webready Con

Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Gonda Indological Studies Published Under the Auspices of the J. Gonda Foundation Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Edited by Peter C. Bisschop (Leiden) Editorial Board Hans T. Bakker (Groningen) Dominic D.S. Goodall (Paris/Pondicherry) Hans Harder (Heidelberg) Stephanie Jamison (Los Angeles) Ellen M. Raven (Leiden) Jonathan A. Silk (Leiden) volume 19 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/gis Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Selected Studies By Henk Bodewitz Edited by Dory Heilijgers Jan Houben Karel van Kooij LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bodewitz, H. W., author. | Heilijgers-Seelen, Dorothea Maria, 1949- editor. Title: Vedic cosmology and ethics : selected studies / by Henk Bodewitz ; edited by Dory Heilijgers, Jan Houben, Karel van Kooij. Description: Boston : Brill, 2019. | Series: Gonda indological studies, ISSN 1382-3442 ; 19 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019013194 (print) | LCCN 2019021868 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004400139 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004398641 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Hindu cosmology. | Hinduism–Doctrines. | Hindu ethics. Classification: LCC B132.C67 (ebook) | LCC B132.C67 B63 2019 (print) | DDC 294.5/2–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013194 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 1382-3442 ISBN 978-90-04-39864-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-40013-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Henk Bodewitz. -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

Preliminary Program Preliminary Pittconium

Inside front and back cover_Layout 1 11/5/14 10:20 AM Page 1 Non-Profit Org. US POSTAGE PAID The Pittsburgh Conference on Analytical Chemistry Mechanicsburg, PA and Applied Spectroscopy, Inc. PERMIT #63 Conferee 300 Penn Center Boulevard, Suite 332 Pittsburgh, PA 15235-5503 USA Exposition Networking Be in your element. 2015 PITTCON 2015 Pi | PRELIMINARY PROGRAM PITTCONIUM Download the New PITTCON 2015 Mobile App The Pittcon 2015 app puts everything Technical Short you need to know about the Program Courses world’s largest annual conference and exposition on laboratory science in the palm of your hand! Just a few of the Pittcon 2015 app features include: • Customizable schedule of events • Technical Program & Short Course listings • Exhibitor profiles & booth locations Preliminary Program • Interactive floor maps • New gaming feature built into app Follow us for special announcements March 8-12, 2015 • Real time messages & alerts New Orleans, LA • Details on local hotels & restaurants Sponsored by Morial Convention Center www.pittcon.org Coming November 2014! Inside front and back cover_Layout 1 11/5/14 10:20 AM Page 2 Thanks to our 2015 Publisher Partners Pittcon is proud to be an Associate Sponsor for the International Year of Light Conferee Exposition Networking and Light-based Technologies (IYL 2015), a cross-disciplinary educational and for Their Continuing Support outreach project with more than 100 partners from over 85 countries. Be in your element. Advanstar Communications IOP Publishing SelectScience 2015 LCGC Asia Pacific Physics -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

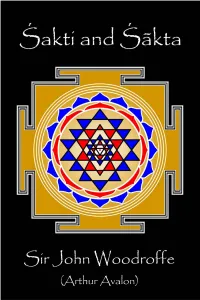

Essays and Addresses on the Śākta Tantra-Śāstra

ŚAKTI AND ŚĀKTA ESSAYS AND ADDRESSES ON THE ŚĀKTA TANTRAŚĀSTRA BY SIR JOHN WOODROFFE THIRD EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED Celephaïs Press Ulthar - Sarkomand - Inquanok – Leeds 2009 First published London: Luzac & co., 1918. Second edition, revised and englarged, London: Luzac and Madras: Ganesh & co., 1919. Third edition, further revised and enlarged, Ganesh / Luzac, 1929; many reprints. This electronic edition issued by Celephaïs Press, somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, and mani(n)fested in the waking world in Leeds, England in the year 2009 of the common error. This work is in the public domain. Release 0.95—06.02.2009 May need furthur proof reading. Please report errors to [email protected] citing release number or revision date. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. HIS edition has been revised and corrected throughout, T and additions have been made to some of the original Chapters. Appendix I of the last edition has been made a new Chapter (VII) in the book, and the former Appendix II has now been attached to Chapter IV. The book has moreover been very considerably enlarged by the addition of eleven new Chapters. New also are the Appendices. The first contains two lectures given by me in French, in 1917, before the Societé Artistique et Literaire Francaise de Calcutta, of which Society Lady Woodroffe was one of the Founders and President. The second represents the sub- stance (published in the French Journal “Le Lotus bleu”) of two lectures I gave in Paris, in the year 1921, before the French Theosophical Society (October 5) and at the Musée Guimet (October 6) at the instance of L’Association Fran- caise des amis de L’Orient. -

Aleuts: an Outline of the Ethnic History

i Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Roza G. Lyapunova Translated by Richard L. Bland ii As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has re- sponsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Shared Beringian Heritage Program at the National Park Service is an international program that rec- ognizes and celebrates the natural resources and cultural heritage shared by the United States and Russia on both sides of the Bering Strait. The program seeks local, national, and international participation in the preservation and understanding of natural resources and protected lands and works to sustain and protect the cultural traditions and subsistence lifestyle of the Native peoples of the Beringia region. Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Author: Roza G. Lyapunova English translation by Richard L. Bland 2017 ISBN-13: 978-0-9965837-1-8 This book’s publication and translations were funded by the National Park Service, Shared Beringian Heritage Program. The book is provided without charge by the National Park Service. To order additional copies, please contact the Shared Beringian Heritage Program ([email protected]). National Park Service Shared Beringian Heritage Program © The Russian text of Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History by Roza G. Lyapunova (Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka” leningradskoe otdelenie, 1987), was translated into English by Richard L. -

The Sanskrit College and University 1, Bankim Chatterjee Street, Kolkata 700073 [Established by the Act No

The Sanskrit College and University 1, Bankim Chatterjee Street, Kolkata 700073 [Established by the Act No. XXXIII of 2015; Vide WB Govt. Notification No 187-L, Dated- 19.02.2016] THREE YEAR B.A HONOURS PROGRAM IN SANSKRIT There will be six semesters in the Three Years B.A (Honours) programme. It is constituted of 14 Core courses, 2 Ability Enhancement Compulsory courses, 2 Skill Enhancement courses, 4 Discipline Specific Elective courses and 4 Interdisciplinary Generic Elective courses. Minimum L/T classes per course is eighty four. Each course is of 50 marks; of which 40 marks is for Semester-End Examination (written) and 10 marks for internal assessment. Out of 10 marks for internal assessment 5 marks is for mid-semester written test and 5 marks is for end-semester viva-voce. B.A.(Honours) in Sanskrit: 1st Semester In this semester, for the Sanskrit Honours Students the Core courses BAHSAN101 and BAHSAN102 and Ability Enhancement Compulsory course UG104ES are compulsory; while they are to opt one Interdisciplinary Generic Elective course from any other Honours subject. Students of any other Honours subject may opt any one of the Interdisciplinary Generic Elective courses BAHSAN103EC and BAHSAN103GM. Course Code Course Title Course type L - T - P Credit Marks BAHSAN101 General Grammar and Metre Core course 4 -2 - 0 6 50 BAHSAN102 Mahākāvya Core course 4 -2 - 0 6 50 BAHSAN103EC Epic Interdisciplinary Generic Elective 4 -2 - 0 6 50 BAHSAN103GM General grammar and Metre Interdisciplinary Generic Elective 4 -2 - 0 6 50 UG104ES Environment Studies Ability Enhancement Compulsory course 3 - I - 0 4 50 Total 22 200 B.A.(Honours) in Sanksrit: 2nd Semester In this semester, for the Sanskrit Honours Students the Core courses BAHSAN201 and BAHSAN202 and Ability Enhancement Compulsory course BAHSAN204E/B are compulsory; while they are to opt one Interdisciplinary Generic Elective course from any other Honours subject. -

Proposal to Encode Symbols of Jainism in Unicode

L2/15-097 2015-03-19 Proposal to Encode Symbols of Jainism in Unicode Anshuman Pandey Department of Linguistics University of Californa, Berkeley Berkeley, California, U.S.A. [email protected] March 19, 2015 1 Introduction This is a proposal to encode four symbols in Unicode that are associated with Jainism. The characters are proposed for inclusion in the block ‘Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs’ (U+1F300). Basic details of the characters are as follows (the actual code points will be assigned if the proposal is approved): glyph code point character name U+1F9xx JAIN SVASTIKA U+1F9xx JAIN HAND U+1F9xx JAIN EMBLEM U+1F9xx JAIN EMBLEM WITH OM 1 Proposal to Encode Symbols of Jainism in Unicode Anshuman Pandey The symbol that appears in the is the Jain depiction of the Hindu symbol ॐ ‘om’ and is an important symbol in the iconography of Jainism. The symbol was proposed for encoding in the ‘Devanagari Extended’ block in 2013 as the character +A8FD (see Pandey 2013). It was accepted for inclusion in the standard and will be published in Unicode 8.0. 2 Background In the proposal “Emoji Additions” (L2/14-174), authored by Mark Davis and Peter Edberg, five ‘religious symbols and structures’ among symbols of other categories were proposed for inclusion as part of the Emoji collection in Unicode. Shervin Afshar and Roozbeh Pournader proposed related symbols in “Emoji and Symbol Additions – Religious Symbols and Structures” (L2/14-235). These characters were approved for inclusion in the standard by the UTC in January 2015. Davis and Edberg made a brief reference to Jain symbols, but did not identify any as candidates for encoding.