Place-Making in Late 19Th And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

'Spaces of Exception: Statelessness and the Experience of Prejudice'

London School of Economics and Political Science HISTORIES OF DISPLACEMENT AND THE CREATION OF POLITICAL SPACE: ‘STATELESSNESS’ AND CITIZENSHIP IN BANGLADESH Victoria Redclift Submitted to the Department of Sociology, LSE, for the degree of PhD, London, July 2011. Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 For Pappu 2 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Declaration I confirm that the following thesis, presented for examination for the degree of PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is entirely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. ____________________ ____________________ Victoria Redclift Date 3 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Abstract In May 2008, at the High Court of Bangladesh, a ‘community’ that has been ‘stateless’ for over thirty five years were finally granted citizenship. Empirical research with this ‘community’ as it negotiates the lines drawn between legal status and statelessness captures an important historical moment. It represents a critical evaluation of the way ‘political space’ is contested at the local level and what this reveals about the nature and boundaries of citizenship. The thesis argues that in certain transition states the construction and contestation of citizenship is more complicated than often discussed. The ‘crafting’ of citizenship since the colonial period has left an indelible mark, and in the specificity of Bangladesh’s historical imagination, access to, and understandings of, citizenship are socially and spatially produced. -

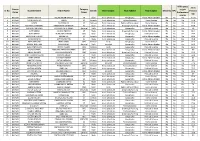

Sr.No. Course Name Student Name Father Name Category Name

Willingness XII th Course Category to join Sr.No. Student Name Father Name Gender Final Subject Final Subject Final Subject Minority BPL Percent Name Name Professional age course 1 BA Part I AAKASH MEENA GULAB SINGH MEENA ST Male Hindi Literature Geography Public Administration No No No 71.14 2 BA Part I AARTI MEROTHA TEJPAL SC Female Hindi Literature Political Science Home Science No Yes No 65.8 3 BA Part I AASHA BAJRANGLAL SC Female Hindi Literature Public Administration Home Science No No No 61.8 4 BA Part I ABHISHEK MEGHWAL RAM KARAN MEGHWAL SC Male Hindi Literature Drawing & Painting Public Administration No No Yes 69.6 5 BA Part I ABHISHEK SHARMA BANVARI LAL SHARMA General Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 59 6 BA Part I AJAY MEENA JAGDISH MEENA ST Male Hindi Literature Drawing & Painting Public Administration No No No 66.4 7 BA Part I AJAY NAGAR SURAJ MAL NAGAR OBC Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 74.4 8 BA Part I AKANKSHA KUMARI PANNA LAL ST Female Hindi Literature Geography Public Administration No No No 83.4 9 BA Part I AKASH KUMAR SATYANARAYAN SC Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 76.8 10 BA Part I AKSA KHANAM IRSAD KHAN OBC Female Urdu Geography Home Science Yes Yes Yes 72.2 11 BA Part I AKSHAT GOUTAM RAMAVATAR General Male Sanskrit Geography Public Administration No No Yes 60.2 12 BA Part I ALISHA MANSURI ZAHID HUSAIN OBC Female Urdu Geography Political Science Yes Yes No 82.6 13 BA Part I ANJALI MEHTA CHANDRA PRAKASH MEHTA OBC Female Hindi Literature -

Community, Nation and Politics in Colonial Bihar (1920-47)

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 10 October 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 COMMUNITY, NATION AND POLITICS IN COLONIAL BIHAR (1920-47) Md Masoom Alam, PhD, JNU Abstract The paper is an attempt to explore, primarily, the nationalist Muslims and their activities in Bihar, since 1937 till 1947. The work, by and large, will discuss the Muslim personalities and institutions which were essentially against the Muslim League and its ideology. This paper will be elaborating many issues related to the Muslims of Bihar during 1920s, 1930s and 1940s such as the Muslim organizations’ and personalities’ fight for the nation and against the League, their contribution in bridging the gulf between Hindus and Muslims and bringing communal harmony in Bihar and others. Moreover, apart from this, the paper will be focusing upon the three core issues of the era, the 1946 elections, the growth of communalism and the exodus of the Bihari Muslims to Dhaka following the elections. The paper seems quite interesting in terms of exploring some of the less or underexplored themes and sub-themes on colonial Bihar and will certainly be a great contribution to the academia. Therefore, surely, it will get its due attention as other provinces of colonial India such as U. P., Bengal, and Punjab. Introduction Most of the writings on India’s partition are mainly focused on the three provinces of British India namely Punjab, Bengal and U. P. Based on these provinces, the writings on the idea of partition and separatism has been generalized with the misperception that partition was essentially a Muslim affair rather a Muslim League affair. -

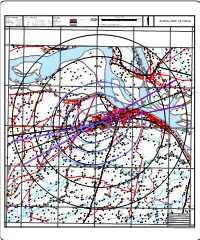

Zoning Map of Patna Telephone Line 2

SCALE 1:50,000 N PATNA AIRPORT LIST OF NAV AIDS LEGEND 0 N 1000 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 M E T E R S V A LATITUDE 25° 35' 37.0"N S.NO. NAV AIDS CO-ORDINATES TOP ELEV. CONTOURS R ROADS . 0 2500 0 2500 5000 7500 10000 12500 15000 17500 20000 22500 F E E T ° LONGITUDE 85° 05' 30.6"E 1. NDB 25° 35' 54.5"N 85° 05' 7.7"E 78.94 M 1 RAILWAY LINE 5 ' W ARP ELEVATION 51.2M(168FT.) 2. DVOR 25° 35' 25.5"N 85° 05' 23.7"E 59.13 M ( ZONING MAP OF PATNA TELEPHONE LINE 2 0 1 AERO ELEVATION 51.8M(170FT.) 3. LLZ 25° 35' 11.87"N 85° 04' 33.55"E 53.77 M 0 POWER LINE ) ALL GEOGRAPHICAL COORDINATES ARE IN WGS-1984. RWY 07/25 2286Mx45M 4. GP 25° 35' 37.67"N 85° 05' 33.50"E 66.22 M RIVER/PONDS/LAKE/TANK/ETC. ALLELEVATIONS.CONTOURS AND DIMENSIONS ARE IN METERS. ANNUAL RATE OF PROP.RWY07/25 2846Mx45M CHANGE-1'E 84° 53' 84° 55' 25° 85° 00' 85° 05' 47' 85° 10' 85° 15' 85° 18' 25° 47' 25° DHANAURANARAON CHHOTKA 0 GORAIPUR SANTHA SANTHA HARAJI 45' MAUZAMPUR FORHADA CHATURPUR MUSEPUR MARKHA CHAK BABANNA MAHALDICHAK GHAT SHEKH DUMRI RAMUTOLA HEMATPUR RAIDIH FATEHABAD PATALI 25° BASATPUR SHIKAR HARPURNAND CHAK ROBIYA THATHAN BUZURG 45' AMI SAIDPUR DIGHWARA BERAI FARANPUR CHAKNUR SHIVRAMPUR MAGHIANI NAINHA RAIPATTI QUTUBPUR KRITPUR SITABGANJ KANS DIYARA JOLAHOTOLA PARMANANDPUR RS 0 ASDHARPUR MURTHAN KALYANPUR PARMANANDPUR DUMRI CHAPTA SIDUARI GOBIND YUSUFPUR GURMJAN MANUPUR BARNAR CHAK MODARPUR GHOSWAR MINAPUR RAI MOAZAMPUR BIROPUR GHAUSPUR IIRA SISAUNI RAJAULI RAHIMPUR SEMARA BAKARPUR MILKI SINGHINPUR SHIVPURA CHAK NURPURWA CHEGHATA ISMAIL CHAK FAKHARABAD -

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Date of joining: 01.08.012 Name: Isha Gaurav Father’s Name: Mr. Brijesh Kumar Date of birth: 05.05.1989 Gender: Female Permanent Address: D/o Mr.Brijesh Kumr C/oLate Raji Ram Prasad New Area Jakkanpur Patna 800 001 Contact: 7870828319 E-mail; [email protected] Languages Known: English. Hindi Educational Qualification: Level Name of Board/University Marks obtained M.Sc Patna University 68.19% B.Sc NOU 75.12% I.Sc BSEB 61.2% Standard Xth CBSE 60 % Persuing PhD from Magadh University. Topic: Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticle by using different Medicinal Plant and its evaluation as an Antimicrobial drug agent. Professional Qulification: Certificte in Computer Application and Offce Practices(Duration24th Nov,2008 to15th Feb,2009).Organization;DOEACC Society,Autonomous body of Department of Information Technology,GOI. Working Exprience: Presently working as Guest Faculty in the department of Botany in Patna Women’s College,Deemed University since 1st August 2012. Achievement: Received Young Scientist Award in 2018 PAPER PRESENTATION Theme of Title of the Paper Date Venue Organizing Agency Level Seminar/worksh op/ Confrence/Symp osium Seminar on Oral Presentation 29th & Bihar Research Topic: Evaluation of 30th National Patna University, Patna Frontiers in 21st Antimicrobial activity May, College, to commemorate its Seminar century of Silver 2018 Patna centenary year. (National) Nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri Seminar on New Poster Presentation 27th & Patna Horizon of (awarded 3rd Prize)/ 28th Women’s Department of Botany & Seminar Biological Topic: A Glimps of Nov, College Industrial Microbiology (National) Sciences: Nanotechnology 2018 Advantages and Challenges. 7th Bihar Science Oral Presentation 4th, 5th & College of Confrence (got Young Scientist 6th Dec, Commerce, BiharBrains Award) 2018 Arts& Development Society Topic: Phytochemical Science, Screening & Patna International biosynthesis of Silver (Seminar) nanoparticles using natural product of Phyllanthus niruri & their Antimicrobial activities. -

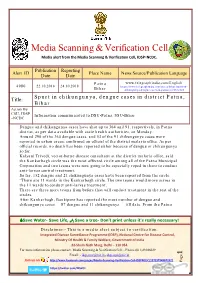

4980, Alert-Spurt in Chikungunya, Dengue Cases in District

Media Scanning & Verification Cell Media alert from the Media Scanning & Verification Cell, IDSP-NCDC. Publication Reporting Alert ID Place Name News Source/Publication Language Date Date Patna www.telegraphindia.com/English 4980 22.10.2018 24.10.2018 https://www.telegraphindia.com/states/bihar/spurt-in- Bihar chikungunya-dengue-cases-in-patna/cid/1672328 Spurt in chikungunya, dengue cases in district Patna, Title: Bihar Action By CSU, IDSP Information communicated to DSU-Patna, SSU-Bihar –NCDC Dengue and chikungunya cases have shot up to 364 and 91, respectively, in Patna district, as per data available with state health authorities, on Monday. Around 290 of the 364 dengue cases, and 53 of the 91 chikungunya cases were reported in urban areas, confirmed an official of the district malaria office. As per official records, no death has been reported either because of dengue or chikungunya so far. Kalyani Trivedi, vector-borne disease consultant at the district malaria office, said the Kankarbagh circle was the most affected circle among all of the Patna Municipal Corporation and two teams were now going to be especially roped in there to conduct anti-larvae control treatment. So far, 152 dengue and 21 chikungunya cases have been reported from the circle. “There are 11 wards in the Kankarbagh circle. The two teams would move across in the 11 wards to conduct anti-larvae treatment. There are three more teams from before that will conduct treatment in the rest of the circles. After Kankarbagh, Bankipore has reported the most number of dengue and chikungunya cases — 87 dengue and 11 chikungunya — till date. -

ERC NCTE Public Notice 7Th Dec, 2017

Annexure - I I Student Details: Number of students course-wise, year -wise along with details: Year of Admission : B.Ed. 2016 - 2018 Admission Name Name Sl.No. Result Address Father's Category Percentage Contact No. Year of Admission fee (Receipt No., Date & Amount) Aditya Kumar Vill - Bari Sirisiyan, P.O. Shobhepur, 1 Shrikant Shahi General 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6078, 30.06.16, 50000 Shahi Bheldi, Saran, Bihar - 841311 Shivaji Nagar, Makhdumpur, 2 Alena Alexander Alexander Ignatius Bageecha, Digha Ghat, Patna - General 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6049, 27.06.16, 50000 800011 Vill + Post - Birpur, P.S.- Shahpur, 3 Amrita Kumari Satyendra Kumar SC 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6030, 28.06.16, 50000 Dist. Bhojpur (Ara), Bihar-802165 Holy Cross Convent, Fair Field 4 Amulya Tirkey Alexius Tirkey General 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6027, 28.06.16, 50000 Colony, Digha Ghat, Patna - 800011 X.T.T.I., Digha Ghat P.O., Patna - 5 Anand Dungdung Philmon DungDung General 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6076, 29.06.16, 80000 800011 Anjali Savia D' Ramna Road, Opposite Patna 6 Albert D' Costa General 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6009, 22.06.16, 50000 Costa University, Patna - 800004 E1/42, Jay Prakash Nagar, Digha 7 Ankita Raj Ganesh Kumar Gupta Ghat, Digha Ashiyana Road, Patna - OBC 2 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6038, 28.06.16, 50000 800011 56 A, Fair Field Colony, Digha Ghat 8 Anuj Biswas Eric John Biswas General 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6010, 28.06.16, 50000 ,Patna - 800011 Flat No. 201, Vaishnavi Umagiri 9 Anuranjan Ekka Anil Benjamin Ekka Apartment, LCT Ghat, Patna - General 2016 Awaited NA 0612-2260253 6052, 29.06.16, 50000 800013 Vikash Nagar, New Colony, Kurji 10 Archana Kumari Nand Kishor Prasad Kothiya, P.O. -

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies Organized by With support from from PRIMUS Visual Histories of South Asia Foreword by Christopher Pinney Edited by Annamaria Motrescu-Mayes and Marcus Banks This book wishes to introduce the scholars of South Asian and Indian History to the in-depth evaluation of visual research methods as the research framework for new historical studies. This volume identifies and evaluates the current developments in visual sociology and digital anthropology, relevant to the study of contemporary South Asian constructions of personal and national identities. This is a unique and excellent contribution to the field of South Asian visual studies, art history and cultural analysis. This text takes an interdisciplinary approach while keeping its focus on the visual, on material cultural and on art and aesthetics. – Professor Kamran Asdar Ali, University of Texas at Austin 978-93-86552-44-0 u Royal 8vo u 312 pp. u 2018 u HB u ` 1495 u $ 71.95 u £ 55 Hidden Histories Religion and Reform in South Asia Edited by Syed Akbar Hyder and Manu Bhagavan Dedicated to Gail Minault, a pioneering scholar of women’s history, Islamic Reformation and Urdu Literature, Hidden Histories raises questions on the role of identity in politics and private life, memory and historical archives. Timely and thought provoking, this book will be of interest to all who wish to study how the diverse and plural past have informed our present. Hidden Histories powerfully defines and celebrates a field that has refused to be occluded by majoritarian currents. – Professor Kamala Visweswaran, University of California, San Diego 978-93-86552-84-6 u Royal 8vo u 324 pp. -

TACR: India: Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41127 March 2011 India: Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector Prepared by MMM Group, Canada Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada For Road Construction Department Government of Bihar This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Asian Development Bank Road Construction Department Government of Bihar FINAL REPORT ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector March 2011 (Updated May 2011) Milestone Report MMM Group, Canada Asian Development Bank Road Construction Department Government of Bihar FINAL REPORT ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector March 2011 (Updated May 2011) Milestone Report MMM Group, Canada Final Report, March 2011 ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector 3 Final Report, March 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Introduction and TA Timeline ........................................................................................ 7 1.2 Interim Report and Mid-term Workshop ........................................................................ 8 1.3 Need for Changes in TA Scope of Work ...................................................................... -

Patna –Azimabad As Socio-Cultural Centre (Part-2) M.A.(History) Sem-2 Paper Cc:7

PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE (PART-2) M.A.(HISTORY) SEM-2 PAPER CC:7 DR. MD. NEYAZ HUSSAIN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR & HOD PG DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAHARAJA COLLEGE, VKSU ARA (BIHAR) PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE The town got a new name-Azimabad- and increased eminence towards the end of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s reign (1658-1707), and during the subahdari of his favourite grandson Prince Azim (d. 1712). The prince got the emperor’s permission to rename the town after himself, around 1704. It may be clarified here that the new name was after the Prince’s personal name, Azim, not his title, ‘Azimu’s Shan’, which he got later in the reign of his father Bahadur Shah (1707-12). The pargan a was also re-named Azimabad , as was the name of the mint. Coins bearing the now mint town, Azimabad, are still available from the year 1705-06 onwards. PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE The Prince got many public buildings constructed or renovated , established charitable institutions and sarais (inns), and encouraged eminent scholars and skilled persons to come and settle in the town. He is said to have made administrative arrangements from the division of the town into different wards, named after the people of different racial groups living there, such as Lodikatra, Mughalpura, etc. or the professional groups settled there, such as Zargartola (embroidery workers’ quarters), Mir Shikar Toli (Bird-Hunters, Falconers, etc.). The Prince wanted to make Azimabad ‘a second Delhi’ . Due to the political upheavals (1707-22) and the blood-bath PATNA –AZIMABAD AS SOCIO-CULTURAL CENTRE at Delhi(1738-39 , Nadir Shah’s sack of Delhi), there was exodus from there, and part of it flowed down to Azimabad.