National Movement and the RSS Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Contest of Indian Secularism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto THE CONTEST OF INDIAN SECULARISM Erja Marjut Hänninen University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Political History Master’s thesis December 2002 Map of India I INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................1 PRESENTATION OF THE TOPIC ....................................................................................................................3 AIMS ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 SOURCES AND LITERATURE ......................................................................................................................7 CONCEPTS ............................................................................................................................................... 12 SECULARISM..............................................................................................................14 MODERNITY ............................................................................................................................................ 14 SECULARISM ........................................................................................................................................... 16 INDIAN SECULARISM .............................................................................................................................. -

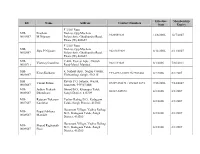

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

Download Article (PDF)

GAJBE : List of Butterfl ies.....observed in Bor Wildlife Sanctuary, Maharashtra ISSN 0375-1511509 Rec. zool. Surv. India : 114(Part-3) : 509-511, 2014 Short Communication LIST OF BUTTERFLIES (INSECTA : LEPIDOPTERA) OBSERVED IN BOR WILDLIFE SANCTUARY, MAHARASHTRA INTRODUCTION The Vidarbha region of Maharashtra has some Bor Wildlife Sanctuary is located in Wardha important conservation areas. Tiple (2011) has District in the state of Maharashtra. The Sanctuary listed the butterfl ies of Vidarbha region. Sharma covers an area of 121.1 km2, which includes the and Radhakrishnan (2005, 2006) have reported the drainage basin of the Bor Dam. The Sanctuary Lepidoptera of Pench National Park and Tadoba is located at a distance of around 60 km from Andhari Tiger Reserve, respectively. Chandrakar Nagpur city. It is situated in the Vidarbha region et al (2007) have studied the butterfl ies of Melghat of Maharashtra, which is characterized by mild region. winters and extremely hot summers. The Sanctuary has South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests. Currently no information is available regarding Many species of animals including major the butterfl ies of Bor Wildlife Sanctuary. During species such as the Bengal Tiger and the Indian the present study, 33 species of butterfl ies Leopard are found here. Among invertebrate fauna, belonging to 22 genera of 5 families of order butterfl ies are probably the most conspicuous. Lepidoptera, observed in and around Bor Wildlife They are mostly diurnal in habit and are well Sanctuary are reported. The study was carried admired for their striking colours and fl ight. Many out during the year 2013. The butterfl ies were species of butterfl ies play an important role in observed around road-side vegetation in the buffer nature by pollinating various species of plants and a few species are economically important as pests zone of the Sanctuary and were identifi ed using of cultivated plants. -

Dr Hedgewar and Sangh April 18 2018 Charcha

Date Topic April 04 2018 Samachar Sameeksha Baudhik –Dr Hedgewar and April 11 2018 Sangh April 18 2018 Charcha :-Moulding Men Katha :-Pujya Adi April 25 2018 Shankaracharya April 04 2018 : Samachar Sameeksha April 11 2018 : Baudhik :-Dr Hedgewar and Sangh ( Article by Swargiya K Suryanarayana Rao ji who was a senior Pracharak and Akhil Bharatiya Karyakarta ) Intro: The daily shakha system of imparting knowledge of character and discipline, removing all the weeds that were dividing the ancient society, to build up an indomitable organised strong Hindu society is RSS founder Dr Hedgewar’s greatest and unique contribution and service to his motherland. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is a very well known organisation. Decades ago, the BBC announced that it is the most wide spread and biggest non-governmental voluntary organisation which is working in India for Hindu consolidation. Since then RSS has grown and spread in multiple proportions. But still, very few, outside sangh circles, know about the founder of this mighty organisation, Dr Keshavrao Balirampanth Hedgewar, popularly known as ‘Doctorji’. Dr Hedgewar was a born patriot, and this instinctive patriotism burst forth at an early age of eight when he threw away the sweets distributed to the school children on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of British Queen Victoria. There are many such occasions which reflect how he grew up manifesting his patriotic nature. He intensely felt that our motherland must be freed from the foreign yoke at any cost and so worked zealously to achieve it by working with revolutionaries, Indian National Congress and Hindu Maha Sabha. -

0001S07 Prashant M.Nijasure F 3/302 Rutu Enclave,Opp.Muchal

Effective Membership ID Name Address Contact Numbers from Expiry F 3/302 Rutu MH- Prashant Enclave,Opp.Muchala 9320089329 12/8/2006 12/7/2007 0001S07 M.Nijasure Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 F 3/302 Rutu MH- Enclave,Opp.Muchala Jilpa P.Nijasure 98210 89329 8/12/2006 8/11/2007 0002S07 Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 MH- C-406, Everest Apts., Church Vianney Castelino 9821133029 8/1/2006 7/30/2011 0003C11 Road-Marol, Mumbai MH- 6, Nishant Apts., Nagraj Colony, Kiran Kulkarni +91-0233-2302125/2303460 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0004S07 Vishrambag, Sangli, 416415 MH- Ravala P.O. Satnoor, Warud, Vasant Futane 07229 238171 / 072143 2871 7/15/2006 7/14/2007 0005S07 Amravati, 444907 MH MH- Jadhav Prakash Bhood B.O., Khanapur Taluk, 02347-249672 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0006S07 Dhondiram Sangli District, 415309 MH- Rajaram Tukaram Vadiye Raibag B.O., Kadegaon 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0007S07 Kumbhar Taluk, Sangli District, 415305 Hanamant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Popat Subhana B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0008S07 Mandale District, 415305 Hanumant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Sharad Raghunath B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0009S07 Pisal District, 415305 MH- Omkar Mukund Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0010S07 Vartak Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Suhas Prabhakar Audumbar B.O., Tasgaon Taluk, 02346-230908, 09960195262 12/11/2007 12/9/2008 0011S07 Patil Sangli District 416303 MH- Vinod Vidyadhar Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0012S07 Gowande Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Shishir Madhav Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0013S07 Govande Sangli District, 415303 MH Patel Pad, Dahanu Road S.O., MH- Mohammed Shahid Dahanu Taluk, Thane District, 11/24/2005 11/23/2006 0014S07 401602 3/4, 1st floor, Sarda Circle, MH- Yash W. -

Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha

@Kamal.Sandesh KamalSandeshLive www.kamalsandesh.org kamal.sandesh @KamalSandesh SPECIAL EDITION 17 September, 2020 `100.00 ABHINANDAN ! Special Edition of Kamal Sandesh on the occasion of 70th birthday of Hon’ble Prime Minister SHRI NARENDRA MODI ARCHITECTARCHITECT OFOF NNEWEWArchitect ofII NewNDINDI India KAMAL SANDESHAA 1 Self-reliant India will stand on five Pillars. First Pillar is Economy, an economy that brings Quantum Jump rather than Incremental change. Second Pillar is Infrastructure, an infrastructure that became the identity of modern India. Third Pillar is Our System. A system that is driven by technology which can fulfill the dreams of the 21st century; a system not based on the policy of the past century. Fourth Pillar is Our Demography. Our Vibrant Demography is our strength in the world’s largest democracy, our source of energy for self-reliant India. The fifth pillar is Demand. The cycle of demand & supply chain in our economy is the strength that needs to be harnessed to its full potential. SHRI NARENDRA MODI Hon’ble Prime Minister of India 2 KAMAL SANDESH Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Bhola Roy Digital Media Rajeev Kumar Vipul Sharma Subscription & Circulation Satish Kumar E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 011-23381428, FAX: 011-23387887 Website: www.kamalsandesh.org 04 EDITORIAL 46 2016 - ‘IndIA IS NOT 70 YEARS OLD BUT THIS JOURNEY IS -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Narendra Modi Tops, Yogi Adityanath Enters List

Vol: 23 | No. 4 | April 2017 | R20 www.opinionexpress.in A MONTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Hindu-Americans divided on Trump’s immigration policy COVER STORY SOARING HIGH The ties between India and Israel were never better The Pioneer Most Powerful Indians in 2017: Narendra Modi tops,OPINI YogiON EXPR AdityanathESS enters list 1 2 OPINION EXPRESS editorial Modi, Yogi & beyond RNI UP–ENG 70032/92, Volume 23, No 4 EDITOR Prashant Tewari – BJP is all set for the ASSOCiate EDITOR Dr Rahul Misra POLITICAL EDITOR second term in 2019 Prakhar Misra he surprise appointment of Yogi Adityanath as Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister post BUREAU CHIEF party’s massive victory in the recently concluded assembly elections indicates that Gopal Chopra (DELHI), Diwakar Shetty BJP/RSS are in mission mode for General Election 2019. The new UP CM will (MUMBAI), Sidhartha Sharma (KOLKATA), T ensure strict saffron legislation, compliance and governance to Lakshmi Devi (BANGALORE ) DIvyash Bajpai (USA), KAPIL DUDAKIA (UNITED KINGDOM) consolidate Hindutva forces. The eighty seats are vital to BJP’s re- Rajiv Agnihotri (MAURITIUS), Romil Raj election in the next parliament. PM Narendra Modi is world class Bhagat (DUBAI), Herman Silochan (CANADA), leader and he is having no parallel leader to challenge his suprem- Dr Shiv Kumar (AUS/NZ) acy in the country. In UP, poor Akhilesh and Rahul were just swept CONTENT partner aside-not by polarization, not by Hindu consolidation but simply by The Pioneer Modi’s far higher voltage personality. Pratham Pravakta However the elections in five states have proved that BJP is not LegaL AdviSORS unbeatable. -

Government Cvcs for Covid Vaccination for 18 Years+ Population

S.No. District Name CVC Name 1 Central Delhi Anglo Arabic SeniorAjmeri Gate 2 Central Delhi Aruna Asaf Ali Hospital DH 3 Central Delhi Balak Ram Hospital 4 Central Delhi Burari Hospital 5 Central Delhi CGHS CG Road PHC 6 Central Delhi CGHS Dev Nagar PHC 7 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Minto Road PHC 8 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Subzi Mandi 9 Central Delhi CGHS Paharganj PHC 10 Central Delhi CGHS Pusa Road PHC 11 Central Delhi Dr. N.C. Joshi Hospital 12 Central Delhi ESI Chuna Mandi Paharganj PHC 13 Central Delhi ESI Dispensary Shastri Nagar 14 Central Delhi G.B.Pant Hospital DH 15 Central Delhi GBSSS KAMLA MARKET 16 Central Delhi GBSSS Ramjas Lane Karol Bagh 17 Central Delhi GBSSS SHAKTI NAGAR 18 Central Delhi GGSS DEPUTY GANJ 19 Central Delhi Girdhari Lal 20 Central Delhi GSBV BURARI 21 Central Delhi Hindu Rao Hosl DH 22 Central Delhi Kasturba Hospital DH 23 Central Delhi Lady Reading Health School PHC 24 Central Delhi Lala Duli Chand Polyclinic 25 Central Delhi LNJP Hospital DH 26 Central Delhi MAIDS 27 Central Delhi MAMC 28 Central Delhi MCD PRI. SCHOOl TRUKMAAN GATE 29 Central Delhi MCD SCHOOL ARUNA NAGAR 30 Central Delhi MCW Bagh Kare Khan PHC 31 Central Delhi MCW Burari PHC 32 Central Delhi MCW Ghanta Ghar PHC 33 Central Delhi MCW Kanchan Puri PHC 34 Central Delhi MCW Nabi Karim PHC 35 Central Delhi MCW Old Rajinder Nagar PHC 36 Central Delhi MH Kamla Nehru CHC 37 Central Delhi MH Shakti Nagar CHC 38 Central Delhi NIGAM PRATIBHA V KAMLA NAGAR 39 Central Delhi Polyclinic Timarpur PHC 40 Central Delhi S.S Jain KP Chandani Chowk 41 Central Delhi S.S.V Burari Polyclinic 42 Central Delhi SalwanSr Sec Sch. -

Y1 Q2 9-12.Pdf

Balagokulam Syllabus April - June Age Group : 9 to 12 Gokulam is the place where Lord Krishna‛s magical days of childhood were spent. It was here that his divine powers came to light. Every child has that spark of divinity within. Bala- Gokulam is a forum for children to discover and manifest that divinity. It will enable Hindu children in US to appreciate their cultural roots and learn Hindu values in an enjoyable manner. This is done through weekly gatherings and planned activities which include games, yoga, stories, shlokas, bhajan, arts and crafts and much more...... Balagokulam is a program of Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Table of Contents April Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ....................................5 Geet ........................................................................................6 Yugadi ....................................................................................7 Stories of Dr. Hedgewar .......................................................10 The Hindu Calendar .............................................................13 Exercise ................................................................................16 Project / Workshop - Art of Story Telling ............................19 May Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ..................................20 Geet ......................................................................................21 Symbols in Hinduism ...........................................................22 The Life of Buddha ..............................................................26 -

In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism

“I recognized two people pulling away my daughter Shabana. My daughter was screaming in pain asking the men to leave her alone. My mind was seething with fear and fury. I could do nothing to help my daughter from being assaulted sexually and tortured to death. My daughter was like a flower, still to see life.Why did they have to do this to her? What kind of men are these? The monsters tore my beloved daughter to pieces.” Medina Mustafa Ismail Sheikh, then in Kalol refugee camp, Panchmahals District, Gujarat This report is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of Indians who have lost their homes, their loved ones or their lives because of the politics of hatred.We stand by those in India struggling for justice, and for a secular, democratic and tolerant future. 2 IN BAD FAITH? BRITISH CHARITY AND HINDU EXTREMISM INFORMATION FOR READERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A separate report summary is available from Any final conclusions of fact or expressions of www.awaazsaw.org. Each section of this opinion are the responsibility of Awaaz – South report also begins with a summary of main Asia Watch Limited alone. Awaaz – South Asia findings. Watch would like to thank numerous individuals and organizations in the UK, India and the US for Section 1 provides brief information on advice and assistance in the preparation of this Hindutva and shows Sewa International UK’s report. Awaaz – South Asia Watch would also like connections with the RSS. Readers familiar to acknowledge the insights of the report The with these areas can skip to: Foreign Exchange of Hate researched by groups in the US. -

The State, Democracy and Social Movements

The Dynamics of Conflict and Peace in Contemporary South Asia This book engages with the concept, true value, and function of democracy in South Asia against the background of real social conditions for the promotion of peaceful development in the region. In the book, the issue of peaceful social development is defined as the con- ditions under which the maintenance of social order and social development is achieved – not by violent compulsion but through the negotiation of intentions or interests among members of society. The book assesses the issue of peaceful social development and demonstrates that the maintenance of such conditions for long periods is a necessary requirement for the political, economic, and cultural development of a society and state. Chapters argue that, through the post-colo- nial historical trajectory of South Asia, it has become commonly understood that democracy is the better, if not the best, political system and value for that purpose. Additionally, the book claims that, while democratization and the deepening of democracy have been broadly discussed in the region, the peace that democracy is supposed to promote has been in serious danger, especially in the 21st century. A timely survey and re-evaluation of democracy and peaceful development in South Asia, this book will be of interest to academics in the field of South Asian Studies, Peace and Conflict Studies and Asian Politics and Security. Minoru Mio is a professor and the director of the Department of Globalization and Humanities at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan. He is one of the series editors of the Routledge New Horizons in South Asian Studies and has co-edited Cities in South Asia (with Crispin Bates, 2015), Human and International Security in India (with Crispin Bates and Akio Tanabe, 2015) and Rethinking Social Exclusion in India (with Abhijit Dasgupta, 2017), also pub- lished by Routledge.