Problems of a Wartime International Lawyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Fallen UN Peacekeepers to Be Awarded Dag Hammarskjöld Medal

List of Fallen UN Peacekeepers to be Awarded the Dag Hammarskjöld Medal Country Rank Name Date of Incident Mission Appointment Type of Nationality Afghanistan Mr. Kafeel GHARSHEEN 5 July 2013 UNAMA National Staff Mr. Zohridden MIRZAHI 23 November 2013 UNAMA National Staff Bangladesh Sainik MD Sanowar HOSSAIN 14 December 2013 MONUSCO Military Corporal Md Rafiqul ISLAM 11 December 2013 MONUSCO Military Leading Anowarul Islam KHAN 14 April 2013 UNIFIL Military SI Mossammat Farida YEASMIN 18 April 2013 MINUSTAH Police ASI Md. Azizur RAHMAN 5 June 2013 UNOCI Police Benin Commandant Brice KEREKOU 11 May 2013 MONUSCO Military Burkina Faso 1e C1 B. Hyppolite BAMOUNI 25 August 2013 UNAMID Military 1e C1 Richard E. Coulibaly 25 August 2013 UNAMID Military 1e C1 Priva Evariste KI 25 August 2013 UNAMID Military Caporal Boubacar LANKOANDE 25 August 2013 UNAMID Military Sergeant Ousmane PANKOLO 28 July 2013 UNAMID Military Chad 2e Cl Zakaria Bechir AHMAT 23 October 2013 MINUSMA Military 2e Cl Mbatssou Z HOURNOU 23 October 2013 MINUSMA Military Private Wory Issa MAHAMAT 22 August 2013 MINUSMA Military Cote d’Ivoire Mr. Guy Hermann YATTE 18 May 2013 UNOCI National Staff DR Congo Mr. Robert DISASHI 1 November 2013 MONUSCO National Staff Mr. Morisho KASIMU 30 October 2013 MONUSCO National Staff Mr. Serge NGOIE MBUYA 25 October 2013 MONUSCO National Staff Egypt Private Amr ATTAYA 18 July 2013 UNAMID Military Private Aly Adel Fathy MAHMOUD 30 September 2013 UNAMID Military Ethiopia Sergeant Adew Halid ADEW 13 April 2013 UNAMID Military Sergeant Zewdu Abiyu WALE 27 July 2013 UNISFA Military Lieutenant Adanech Birhane HAILESLASSIE 30 September 2013 UNAMID Military Private Mesert Lemlem NREA 14 June 2013 UNISFA Military Corporal Genetu Haile WOLDEGEBRIEL 4 May 2013 UNISFA Military 1 France Mr. -

The Gazette of India

REGD. N0. D-222 The Gazette of India PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 38] NEW DELHI, SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1963/BHADRA 30, 1885 PART I—SECTION 4 Notifications regarding Appointments, Promotions, Leave, etc. of Officers issued by the Ministry of Defence MINISTRY OF DEFENCE No. 2042, dated 4th Sep. 1963.—Shri Sunil Kumar Khas- MINISTRY OF DEFENCE nobis, offg. Jr. Scientific Officer, Defence Metallurgical Research New Delhi, 21st September 1963 Laboratory, Ichapur relinquished charge of his post on 6th No. 2037, dated 6th Sep. 1963.—The President is pleased July 1963 (AN.) consequent on acceptance of his resignation. to appoint Shri K. Ramanujam, IAS, Under Secy., M. of D. G. JAYARAMAN, Under Secy. as Dy. Secy, in the Ministry, w.e.f. 4th Sep. 1963 (F.N.). YATINDRA SINGH, Under Secy INDIAN ORDNANCE FACTORIES SERVICE No. 2041, dated 6th Sep. 1963.—The President is pleased DEFENCE PRODUCTION ORGANISATION to appoint the following as Assistant Manager (on probn.) No. 2038, dated 1th Sep. 1963.—The President is pleased from the dates noted against each, until further orders :— to make the following promotion : — Shri Vilapakkam Natesapillai Pattabiraman, 16th Nov. 1962. Defence Science Service Shri Sankaran Narayanaswamy, 1st Dec. 1962. Shri Prabudh Kumar Bhasker Prasad MEHTA, permit. Sr. Shri Musuvathy Hananandan Jeyachandran, 11th Dec. 1962. Scientific Asstt., Inspectorate of General Stores, West India, No. 2044, dated 5th Sep. 1963,—The President is pleased BOMBAY to be oftg. Jr. Scientific Officer, Inspectorate of to appoint Shri Laxmi Chand KALIA, offg. Foreman (permt, General Stores, Central India, KANPUR, 13th May 1963 Asstt. Foreman), as offg. Asstt. -

Human Resource Management in the Armed Forces| 1

Human Resource Management in the Armed Forces| 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 54 August 2016 Human Resource Management in the Armed Forces Transition of a Soldier to a Second Career Pardeep Sofat 2 | Pardeep Sofat Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-67-3 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Monograph are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. First Published: August 2016 Price: Rs. 175/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Layout & Cover by: Vaijayanti Patankar Printed at: M/S Manipal Technologies Ltd. Human Resource Management in the Armed Forces| 3 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2 Contextualizing a Soldiers' Early Retirement and Transition .................................................................. 10 Chapter 3 Challenges and Concerns .................................................................... 29 Chapter 4 Veteran Affairs in Foreign Armies ................................................... 51 Chapter 5 Opportunities and the Way Forward .............................................. 60 Annexures ................................................................................................. 93 4 | Pardeep Sofat List of Tables Table 2.1 Terms and Conditions for Sepoys ............................. 14 Table 2.2 Terms and Conditions for Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) .................... 15 Table 2.3 Terms and Conditions for JCOs ............................... -

Alison Safadi

alison safadi From Sepoy to Subadar / Khvab-o-Khayal and Douglas Craven Phillott Introduction During the 1970s John Borthwick Gilchrist, convinced of the potential value of the language he called ìHindustani,î1 campaigned hard to raise its status to that of the ìclassicalî languages (Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit) which, until then, had been perceived by the British to be more important than the Indian ìvernaculars.î By 1796 he had already made a valuable contribution to its study with the publication of his dictionary and gram- mar. It was the opening of Fort William College in 1800 by Wellesley, however, that signaled the beginning of the colonial stateís official interest in the language. Understandably, given his pioneering work, a substantial amount has been written on Gilchrist. Much less attention has been paid to the long line of British scholars, missionaries, and military officers who published Hindustani grammars and textbooks over the next 150 years. Although such books continued to be published until 1947, British scholarly interest in Hindustani seemed to have waned by the beginning of World War I. While Gilchrist and earlier authors had aspired to producing literary works, later textbooks were generally written for a much more mundane 1Defining the term ìHindustaniî satisfactorily is problematic but this is not the place to rehearse or debate the often contentious arguments surrounding Urdu/ Hindi/Hindustani. Definitions used by the British grammar and textbook writers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are inconsistent and often contradictory. For the purposes of this paper, therefore, I am using the term in its widest possible sense: to cover the language at all levels, from the literary (Persianized) Bāgh-o- Bahar and (Persian-free) Prem Sagur to the basic ìlanguage of commandî of the twentieth-century military grammars. -

OA 97 of 2015.Pdf

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI O.A.NO.97 of 2015 WEDNESDAY, THE 17TH DAY OF FEBRUARY,2016/28TH MAGHA, 1937 CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE S.S.SATHEESACHANDRAN, MEMBER (J) HON'BLE VICE ADMIRAL M.P.MURALIDHARAN, AVSM & BAR, NM, MEMBER (A) APPLICANTS: 1.T.GEORGE, EX AAW II, NO.051799A VALIPLACKAL HOUSE, CHOTTANIKKARA.P.O., ERNAKULAM, KERALA – 682 312. 2.P.R.SUBRAMANIAN, EX EAAR II, NO.051414, PAZHAMPILLY HOUSE, EDAVANAKKAD.P.O., ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA 682 502. 3.K.M.SHAMSUDDIN, EX ERA II, NO.051645A, KATTUTHANIPARAMBIL, NETTOOR.P.O., ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA 682 040. BY ADV.MR.V.K.SATHYANATHAN. Versus RESPONDENTS: 1.UNION OF INDIA, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE, SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 011. 2.THE CHIEF OF NAVAL STAFF, INTEGRATED HEADQUARTERS OF MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (NAVY) NEW DELHI 110 011. 3.THE COMMODORE, BUREAU OF SAILORS, CHEETAH CAMP, MANKHURD, MUMBAI – 400 088. 4. THE PRINCIPAL CONTROLLER OF DEFENCE ACCOUNTS (PENSIONS), OFFICE OF THE P.C.D.A.(P), DRAUPADI GHAT, ALLAHABAD, UP - 211 014. BY ADV.SHRI P.J.PHILIP, CENTRAL GOVT. COUNSEL. OA No. 97 of 2015 : 2 : O R D E R VAdm.M.P.Muralidharan, Member (A): 1. The Original Application has been filed jointly by three applicants for rectification of alleged anomalies in fixation of their pension. 2. Applicant No.1, T.George, Ex AAW II, No.051799A was enrolled in the Navy on 27 January 1968 as Artificer Apprentice and was discharged from service on 31 January 1982 on completion of engagement period after serving 14 years and 04 days. -

JCO Notification.Pdf

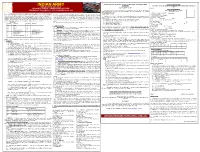

INSTRUCTIONS FOR ONLINE APPLICATION : JCO (RT) PANDIT, GRANTHI AND PADRE APPLICATION PROFORMA INDIAN ARMY CATEGORIES FOR PANDIT (GORKHA), MAULVI (SHIA) AND BODH MONK (MAHAYANA) CANDIDATES www.joinindianarmy.nic.in ONLY HOW TO APPLY ONLINE Roll No ______________ BECOME A JUNIOR COMMISSIONED OFFICER PART I : PERSONAL DATA (RELIGIOUS TEACHER) JCO (RT) COURSES 80, 81 & 82 1. Recruitment of Junior Commissioned Officer (Religious Teacher) for Pandit, Granthi and RRT COURSE SER NO 80, 81 & 82 Padre categories will be through the online registration and online application on our website (Fill in Block Letters) www.joinindianarmy.nic.in. 1. Name in full (Block Capitals) : __________ 1. Applications are invited from eligible male candidates for recruitment of Religious ONLINE REGISTRATION (Do not use initials) Teachers in Indian Army as Junior Commissioned Officer for RRT 80, 81 & 82 courses. Religious (f) The list of finally selected candidates will be displayed at their respective HQ Recruiting 2. Father’s Name (Block Capitals) : __________ Teachers preach religious scriptures to troops and conduct various rituals at Regimental/Unit Zones by 04 May 2016. Recruiting organization will not be responsible for non receipt of 2. Candidates can “check their eligibility” on www.joinindianarmy.nic.in and can apply online for 3. Permanent Home Address :- religious institutions. Their duties also include attending funerals, ministering to the sick in communication due to postal errors and incorrect/incomplete address furnished by the candidates. chosen -

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007 Mark Fraser Briskey A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW School of Humanities and Social Sciences 04 July 2014 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). I have either used no substantial portions of copyright material in my thesis or I have obtained permission to use copyright material; where permission has not been granted I have applied/ ·11 apply for a partial restriction of the digital copy of my thesis or dissertation.' Signed t... 11.1:/.1!??7 Date ...................... /-~ ....!VP.<(. ~~~-:V.: .. ......2 .'?. I L( AUTHENTICITY STATEMENT 'I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor Y, riations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.' · . /11 ,/.tf~1fA; Signed ...................................................../ ............... Date . -

An Investigation Into the Gurkhas' Position in The

THE WAY OF THE GURKHA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE GURKHAS’ POSITION IN THE BRITISH ARMY Thesis submitted to Kingston University in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Mulibir Rai Faculty of Arts and Social Science Kingston University 2018 1 2 CONTENTS The thesis contains: Documentary: The Way of the Gurkha Script/Director/Presenter/Editor/Cinematographer: Mulibir Rai Cast: Mulibir Rai, Karan Rai, Sarbada Rai, Deshu Rai, Shanta Maya Limbu, Kesharbahadur Rai, Yamkumar Rai, Dipendra Rai, Rastrakumar Rai, Bambahadur Thapa, Tiloksing Rai, Lt Col JNB Birch, Maj R Anderson, Gajendra K.C, Sophy Rai, Chandra Subba Gurung, Lt Col (retired) J. P. Cross, Major (retired) Tikendradal Dewan, Gyanraj Rai, Padam Gurung, D.B. Rai, Recruit intake 2012. Genre: Documentary Run time: 1:33:26 Medium: High definition Synopsis – The documentary is divided into two parts. In the first part, the researcher, in 2012 returned to his village of Chautara in Eastern Nepal where he was born, raised and educated for the first time in 13 years. He found many changes in the village - mainly in transport and information technology, but no improvement in the standard of English teaching which nowadays, unlike in the past, is one of the necessities required for joining the British Army. Hence, the hillboys pay a significant amount of money to the training academies in the cities to improve their English. In the end, only a few out of thousands of candidates achieve success. They fly to the UK and receive nine months training at Catterick Garrison Training Centre before joining their respective regiments as fully-fledged Gurkha soldiers. -

Imperial Influence on the Postcolonial Indian Army, 1945-1973

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2017 Imperial Influence On The oP stcolonial Indian Army, 1945-1973 Robin James Fitch-McCullough University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Fitch-McCullough, Robin James, "Imperial Influence On The osP tcolonial Indian Army, 1945-1973" (2017). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 763. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/763 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMPERIAL INFLUENCE ON THE POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN ARMY, 1945-1973 A Thesis Presented by Robin Fitch-McCullough to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History October, 2017 Defense Date: May 4th, 2016 Thesis Examination Committee: Abigail McGowan, Ph.D, Advisor Paul Deslandes, Ph.D, Chairperson Pablo Bose, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT The British Indian Army, formed from the old presidency armies of the East India Company in 1895, was one of the pillars upon which Britain’s world empire rested. While much has been written on the colonial and global campaigns fought by the Indian Army as a tool of imperial power, comparatively little has been written about the transition of the army from British to Indian control after the end of the Second World War. -

Ranks of Indian Armed Forces

RanksA of Indian Army, Navy & Air Force Article Indian Army is the world’s largest volunteer army in the world. It is ranked as the third largest armed forces. Many of you are eager to join the army so today here we are providing you with ranks of the Indian Army. This information is very important for those who appear in the SSB interview, as it is seen that the assessor asks about the equivalent ranks of officers of armed forces. This is very critical to create a good impression on him. The ranks of the Indian Army are categorized into: Commissioned Officers Personnel Below Officer Rank Commissioned Officers: They are Grade - A officers who join the Indian Army through exams such as NDA, CDS, TGC, TES, TA etc. They lead the men into the battlefield & command platoon/company to brigades, division, corps, and the whole army. Personnel Below Officer Rank (PBOR): They are soldiers who execute responsibilities assigned to them by the commissioned officers. They are recruited through exams like Air Force Group X & Y, Indian Navy SSR, MR, and AA. They are further classified into: JCO’s (Junior Commissioned Officer) NCO’s (Non - Commissioned Officer) Here is the table that provides information about equivalent ranks in the armed forces: Ranks of Officers of Armed Forces Indian Army Indian Navy Indian Air Force Field Marshal Admiral of the Fleet Marshal of the Air Force General Admiral Air Chief Marshal Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Air Marshal Major General Rear Admiral Air Vice Marshal Brigadier Commodore Air Commodore Colonel Captain -

The Jullundur Brigade

www.lancashire.gov.uk/museums The Jullundur Brigade 1 Foreword Foreword by Brigadier Peter Rafferty MBE, and creeds fought together in the defence Colonel, The Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment, of Freedom. It is to commemorate their ‘the Lions of England’. deeds and ensure they are not forgotten, that the ‘Jullundur Project’ was conceived as In October 1914 the Jullundur Brigade was a reflective and educational journey. one of the first brigades from the Indian Army to go into action on the Western Front. Throughout this project we have worked Within the brigade, beside battalions ‘hand in glove’ with our partners in the from what is today India and Pakistan, Lancashire County Council Heritage Learning was also the 1st Battalion the Manchester Team. This joint working has been invaluable Regiment, one of the ancestors of The Duke and has enabled the project’s educational of Lancaster’s Regiment, which today is aspects to be expertly captured. Equally the Infantry Regiment of the North West important was the participation of Year Six of England. It is also worth noting that the Primary School Pupils, from 14 schools in diverse make up of the brigade is reflected Lancashire and Greater Manchester. in the North West today. The culmination of the Jullundur Project is The story of the Jullundur Brigade is a proud this e learning resource pack, intended for part of our regimental history and one we primary schools nationally. It contains the wanted to commemorate. But there is also outstanding work of the budding young much to learn for today from the courage historians from the schools who took part and sacrifice of the brigade, when soldiers in the project. -

Mangal Pandey: Drug-Crazed Fanatic Or Canny Revolutionary? Richard Forster 3

THE COLUMBIA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES Volume I Issue I THE COLUMBIA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES Volume I · Issue I Fall 2009 Editorial Collective Founding Editor-in-Chief: Nishant Batsha Editors: Sarah Khan Leeza Mangaldas Mallika Narain Samiha Rahman The Columbia Undergraduate Journal of South Asian Studies (CUJSAS) is a web-only academic journal based out of Columbia University. The journal is a space for undergraduates to publish their original research on South Asia (Ban- gladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) from both the social sciences and humanities. It is published biannually in the spring and the fall. http://www.columbia.edu/cu/cujsas ISSN: 2151-4801 All work within the Columbia Undergraduate Journal of South Asian Studies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Editor 1 About the Authors 2 Mangal Pandey: Drug-crazed Fanatic or Canny Revolutionary? Richard Forster 3 The Rise of Kashmiriyat: People Building in 20th Century Kashmir Karan Arakotaram 26 Oppression2: Indian Independent Documentaries’ Ongoing Struggle for View- ership John Fischer 41 ii LETTER FROM THE EDITOR The interlocutor is often given an unfair reputation. Edward Said once referred to it as “someone who has perhaps been found clamoring on the doorstep, where from outside a discipline or field he or she has made so unseemly a disturbance as to be let in, guns or stones checked in with the porter, for further discussion.”1 Though Said readily admits that his definition is somewhat antiseptic, one needs to remember that the interlocutor carries an ability to intervene in the historical trajectories of strands of minutia.