Issue 2 November 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Staff Publications List

Staff Publications 1998 Published by the Research Policy Office Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington, New Zealand ISSN 1174-121X CONTENTS FACULTY OF COMMERCE AND ADMINISTRATION 3 Accounting and Commercial Law, School of 3 Business and Public Management, School of 5 Communications and Information Systems Management, School of 11 Economics and Finance, School of 13 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES 16 Anthropology 16 Art History 17 Asian Languages 18 Classics 19 Criminology, Institute of 20 Education, School of 22 Institute for Early Childhood Studies 24 English, Film and Theatre, School of 25 European Languages 32 History 33 Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, School of 36 Maori Studies: Te Kawa a Maui, School of 41 Music, School of 41 Nursing and Midwifery 43 Philosophy 45 Political Science and International Relations, School of 46 Sociology and Social policy 47 Women’s Studies 49 FACULTY OF LAW 51 FACULTY OF SCIENCE 54 Architecture, School of 54 Biological Sciences, School of 58 Chemical and Physical Sciences, School of 63 Earth Sciences, School of 65 Mathematical and Computing Sciences, School of 70 Psychology, School of 80 UNIVERSITY INSTITUTES AND CENTRES 82 Centre for Continuing Education/Te Whare Pukenga 82 Health Services Research Centre 83 Institute of Policy Studies 84 University Teaching Development Centre 85 Centre for Strategic Studies 85 Stout Research Centre 86 2 1998 Staff Publications FACULTY OF COMMERCE AND ADMINISTRATION ACCOUNTING AND COMMERCIAL LAW 3. Articles/Chapters/Conference Papers Articles Anderson, Gordon, ‘Interpreting the Employment Contracts Act: Are the Courts Undermining the Act?’, California Western International Law Journal, 28 (1997), pp. -

Chch Star Poets Index and Notes

Supplement to broadsheet: new new zealand poetry no. 12 Index to the Star Poets of Christchurch 1922-26 and Field Notes by Mark Pirie (Includes notes on poets: Bessie L Heighton, Una Auld/Una Currie, Ida M Lough/Ida M Withers, R D Brown, T E L Roberts, H H Heatley, H S Gipps, A Stanley Sherratt, Beryl Windsor, Grace Ross, E A Irwin, W J McKellow, Dorothy Reed, E F Owen, Aline Dunn, Sadie Uanson, G R Butler, Honor Gordon Coster/Honor Gordon Holmes, Pearl Noonan and H Tillman) Published by The Night Press, Wellington ISSN 1178-7805 (Print) ISSN 1178-7813 (Online) Publisher’s Note This supplement to the special issue of broadsheet, no. 12, includes the full index to the Star Poets of Christchurch 1922-26 and the stats relating to their contributions to The Star. It should be noted that I may have missed a few poems here and there as I’ve only checked Saturday publications of The Star for these years, and I can’t be certain that there weren’t occasional midweek publications of poems. Some issues like the supplement to Saturday 2 August 1924 were missing (in micro film runs) and it’s likely Sherratt’s 25th Polynesian legend (of the 30) appeared that weekend. I’ve only included local NZ poets in the Index from the Saturday poetry page 'Among the Poets'. Overseas poets appeared as well, reproduced from overseas magazines and collections. These overseas poets are not in the Index. There were also two regular (unsigned) doggerel columns: 'Spindrifts' and 'Things Thoughtful' and I've not indexed these columns. -

Poetry Notes

. Poetry Notes Winter 2010 Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 1179-7681 Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA humanism, largely purveyed by Inside this Issue Welcome journalists writing in rhyme. In Australia up to about 1910 both these Hello and welcome to the second issue poles exist in symbiosis in the Bulletin. Welcome of Poetry Notes, the newsletter of Although the same poles are found in 1 PANZA, the newly formed Poetry Australia, in Aotearoa they are given a Archive of New Zealand Aotearoa. local authenticity through the local Niel Wright on John Liddell Poetry Notes will be published quarterly colour, particularly the Polynesian and will include information about Kelly’s Heine translations background. goings on at the Archive, articles on At its best in Aotearoa the intellectual historical New Zealand poets of interest, Poetry Archive opening humanism takes Heine and Nietzsche as occasional poems by invited poets and a its masters. German literature is much and book launch 3 record of recently received donations to the most influential; it is still strong on the Archive. Ursula Bethell. Georg Trakl translations The newsletter will be available for free However, although the characteristics of 5 by Nelson Wattie download from the Poetry Archive’s this literature are clear, its success is web site: almost nil. This is because of the endemic banality and facileness which Classic New Zealand http://poetryarchivenz.wordpress.com 6 poetry blight its productions almost totally. Only an occasional poem shows the slightest merit. The established culture Comment by Ivan (jingoistic British Imperialism) and Bootham Niel Wright on John journalism saturated with Sir Walter Liddell Kelly’s Heine Scott’s verse style are the source of New publication by these blights. -

J.C. Sturm – Before the Silence: an Exploration of Her Early Writing

J. C. STURM: BEFORE THE SILENCE An exploration of her early writing By Margaret Erica Michael A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2013 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 6 Chapter 2: J. C. Sturm: Social Informer – “An unequal and discomforted world” 27 Chapter 3: J. C. Sturm: Woman Writer – “Writing against the current” 41 Chapter 4: J. C. Sturm: Maori Writer – “A way of feeling” 58 Chapter 5: “The Long Forgetting” 71 Bibliography 84 3 Abstract This thesis considers the early works of J. C. Sturm, her own thesis, her short stories, articles and book reviews written in the 1950s before her writing and publishing silence. It examines where this writing places her in context of the post-Second World War period and where it could have placed her in the New Zealand literary canon had it not been for her ensuing literary silence. The first chapter briefly discusses the nature of literary silences and then introduces Sturm with some biographical information. It details the approach that I take writing the thesis using three readings of her works: as social informer; as woman writer; and as Maori writer. These readings inform my commentary on her work and attempt to place her in the literary canon of the fifties. I discuss my reservations, as a Pakeha, in approaching Sturm as a Maori writer. I use Sturm’s own comments “that many literary works can be taken as social documents and many authors can be taken as social informers” as a licence to use Sturm herself as “social informer”. -

Denis Glover

LA:J\(JJFA LL ' Zealam 'terly 'Y' and v.,,,.,,,,,,.,.,,," by 1 'On ,,'re CON'I'EN'TS Notes 3 City and Suburban, Frank Sargeson 4 Poems of the Mid-Sixties, K. 0. Arvidson, Peter Bland, Basil Dowling, Denis Glover, Paul Henderson, Kevin Ireland, Louis Johnson, Owen Leeming, Raymond Ward, Hubert Witheford, Mark Young 10 Artist, Michael Gifkins 33 Poems from the Panjabi, Amrita Pritam 36 Beginnings, Janet Frame 40 A Reading of Denis Glover, Alan Roddick 48 COMMENTARIES; Indian Letter, Mahendra Kulasrestha 58 Greer Twiss, Paul Beadle 63 After the Wedding, Kirsty Northcote-Bade 65 REVIEWS: A Walk on the Beach, Dennis McEldowney 67 The Cunninghams, Children of the Poor, K. 0. Arvidson 69 Bread and a Pension, MacD. P. Jackson 74 Wild Honey, J. E. P. T homson 83 Ambulando, R. L. P. Jackson 86 Byron the Poet, !an Jack 89 Studies of a Small Democracy, W. J. Gardner 91 Correspondence, W. K. Mcllroy, Lawrence Jones, Atihana Johns 95 Sculpture by Greer T wiss Cover design by V ere Dudgeon VOLUME NINETEEN NUMBER ONE MARCH 1965 LANDFALL is published with the aid of a grant from the New Zealand Literary Fund. LANDFALL is printed and published by The Caxton Press at 119 Victoria Street, Christchurch. The annual subscription is 20s. net post free, and should be sent to the above address. All contributions used will be paid for. Manuscripts should be sent to the editor at the above address; they cannot be returned unless accompanied by a stamped and addressed envelope. Notes PoETs themselves pass judgment on what they say by their way of saying it. -

Jam Inspire Create Join Make Collect Slam Own Rap Known Read W Rite

Jam Slam Rap Read Join Write Create Recite Make 20/20 Forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant voices in our contemporary literature Admire Collect Inspire Known Own 20 ACCLAIMED KIWI POETS - 1 OF THEIR OWN POEMS + 1 WORK OF ANOTHER POET To mark the 20th anniversary of Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, we asked 20 acclaimed Kiwi poets to choose one of their own poems – a work that spoke to New Zealand now. They were also asked to select a poem by another poet they saw as essential reading in 2017. The result is the 20/20 Collection, a selection of forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant range of voices in New Zealand’s contemporary literature. Published in 2017 by The New Zealand Book Awards Trust www.nzbookawards.nz Copyright in the poems remains with the poets and publishers as detailed, and they may not be reproduced without their prior permission. Concept design: Unsworth Shepherd Typesetting: Sarah Elworthy Project co-ordinator: Harley Hern Cover image: Tyler Lastovich on Unsplash (Flooded Jetty) National Poetry Day has been running continuously since 1997 and is celebrated on the last Friday in August. It is administered by the New Zealand Book Awards Trust, and for the past two years has benefited from the wonderful support of street poster company Phantom Billstickers. PAULA GREEN PAGE 20 APIRANA TAYLOR PAGE 17 JENNY BORNHOLDT PAGE 16 Paula Green is a poet, reviewer, anthologist, VINCENT O’SULLIVAN PAGE 22 Apirana Taylor is from the Ngati Porou, Te Whanau a Apanui, and Ngati Ruanui tribes, and also Pakeha Jenny Bornholdt was born in Lower Hutt in 1960 children’s author, book-award judge and blogger. -

February 2004

New Zealand Poetry Society PO Box 5283 7KH1HZ=HDODQG Lambton Quay 3RHWU\6RFLHW\ WELLINGTON Patrons Dame Fiona Kidman Vincent O’Sullivan Te Hunga Tito Ruri o Aotearoa President Margaret Vos With the assistance of Creative NZ Email: [email protected] Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa Website: www.poetrysociety.org.nz Poetry can be at times something of a risky venture, taking you mentally to places or notions you might not F 7KLV0RQWKV0HHWLQJ G have come across before. Or even more disconcertingly, where you have been but with not quite the frame of mind of the writer, as with this summer idyll from Australian poet Judith Beveridge in her sequence Ten poems in the Michael Harlow voice of Siddatha Gotama as he wanders the forest: Thursday February 19th 2004 Today has an easy somnolence. 8 p.m. Winds drift and my head nods. Turnbull House This wheat is a hypnotist’s chain Wellington swaying up remembrance. Scents mingle, then carry me off by my disparate parts. preceded by an open reading I’m no expert on Buddhism but clearly the smell of the wheat field reclaims the senses, and sets off an explosion of memories as if he’s suddenly and irresistibly split into Is reading poetry good for you? the past selves and events that make up the Siddatha of the poem. by Bernard Gadd R. A. K. Mason suggests a use for poetry for those who nod out of sync with the great and the powerful: Poetry can confirm who you are and your ideas and If the drink that satisfied feelings. -

Montague Harry Holcroft, 1902 – 1993

150 Montague Harry Holcroft, 1902 – 1993 Stephen Hamilton Born in Rangiora on the South Island of New Zealand on 14 May 1902, Montague Harry Holcroft was the son of a grocer and his wife and the second of three boys. When his father’s business failed in 1917, he was forced to leave school and begin his working life in the office of a biscuit factory. Two years later he abandoned his desk in search of adventure, working on farms throughout New Zealand before crossing the Tasman Sea to Sydney, Australia in the company of his friend Mark Lund. Here he returned to office work and married his first wife, Eileen McLean, shortly before his 21st birthday. Within three years the marriage ended and Holcroft returned to New Zealand. However, during his sojourn in Sydney his emerging passion for writing had borne fruit in stories published in several major Australian magazines. With aspirations to become a successful fiction writer, he submitted a manuscript to London publisher John Long. Beyond the Breakers appeared in 1928. After a brief interlude on the staff of a failing Christchurch newspaper, he departed for London in late 1928 with a second novel stowed among his luggage. Despite having stories accepted by a number of British magazines, London proved unsympathetic to his efforts, even after a second novel, The Flameless Fire, appeared in 1929. After visiting France and North Africa, and with the Depression beginning to bite, Holcroft elected to again return to New Zealand. In Wellington in July 1931 he married Aralia Jaslie Seldon Dale. -

View Complete Text Here

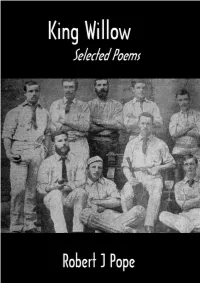

1 Robert J Pope (1865-1949) was a well- known Wellington poet, cricketer and songwriter in his day and till the end of the 1940s he held a reputation as a national songwriter for his school song New Zealand, My Homeland but today, his work is little known and out of print. Popes poetry, lyrically gifted, showed musical flair and easy felicity of rhyme. He began writing and publishing in earnest during the Edwardian era, and his work notably covers the two world wars and the national politics of the period, 1902-1944. His most interesting work concerns sporting verse on the 1924/25 All Blacks Invincibles tour of Great Britain and France and suburban satires on Wellington city-life. Pope was a leading light verse parodist of his day, publishing mainly in the Free Lance and The Evening Post, and was a precursor to the Wellington group of the 1950s. This selection gives a substantial picture of the man and his times and restores a significant New Zealand poet. Previously uncollected and unpublished poems accompany selections from Popes two published books. An appendix includes a selection of his prose writings, including his Wellington club cricket essay and sporting contorts and retorts. Mark Pirie is a Wellington poet, anthologist, critic and editor. He currently co-organises the Poetry Archive of New Zealand Aotearoa with Dr Niel Wright and Dr Michael OLeary. His books include A Tingling Catch: A Century of New Zealand Cricket Poems 1864-2009. Cover photo: Star Clubs Pearce Cup winning team of 1883/84, from The Evening Post, 1929 Author -

Poetry Notes

. Poetry Notes Winter 2011 Volume 2, Issue 2 ISSN 1179-7681 Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA of New Zealand Literature: being a List Inside this Issue Welcome of New Zealand Authors and their works with introductory essays and Hello and welcome to the sixth issue of verses, page 59: Gerard, Kate, with a Welcome Poetry Notes, the newsletter of PANZA, full list of her 13 books of poetry and 1 the newly formed Poetry Archive of page 55: Eyre, Ernest Leonard, with Niel Wright on two classic New Zealand Aotearoa. 1906 Future times and other rhymes, NZ poets: Kate Gerard and Poetry Notes will be published quarterly and 1918 In the bush and other verses Ernest L. Eyre and will include information about (2nd edition), but nothing else. goings on at the Archive, articles on Obituary: David Mitchell historical New Zealand poets of interest, occasional poems by invited poets and a KATE GERARD 3 record of recently received donations to Tributes to David Mitchell the Archive. by Michael O’Leary and The National Library on line catalogue 4 The newsletter will be available for free Ron Riddell credits her with 14 book publications, download from the Poetry Archive’s and gives her dates as 1855-1934, so Classic New Zealand website: she lived to 79. poetry by Rex Hunter There is no trace of any other forenames 6 http://poetryarchivenz.wordpress.com American-born NZ busker for her than Kate. The name Kate and poet ‘Kenny’ dies Gerard does not appear in New Zealand 8 Biographies at the National Library, but Niel Wright on two Tapuhi has correspondence of hers in Comment on the Alistair various files. -

New Zealand Compiled and Introduced by Kirstine Moffat University of Waikato Introduction 2008 Saw the Passing of Two Well-Loved

New Zealand Compiled and introduced by Kirstine Moffat University of Waikato Introduction 2008 saw the passing of two well-loved and critically acclaimed New Zealand poets: Hone Tuwhare (1922-2008) and Ruth Dallas (1919-2008). Among his many literary awards, Tuwhare earned the Prime Minister‘s Award for Literary Achievement, the Te Mata New Zealand Poet Laureateship, and honorary doctorates from Otago and Auckland Universities. Speaking of Tuwhare‘s enduring legacy Robert Sullivan writes: I use the term work for Tuwhare‘s oeuvre because he was brilliantly and humbly aware of his role as a worker, part of a greater class and cultural struggle. His humility is also deeply Māori, and firmly places him as a rangatira of people and poets. It goes without saying that this tribute acknowledges the passing of a very (which adverb to use here – greatly? hugely? extraordinarily?) significant New Zealand poet, and the first Māori author of a literary collection to be published in English. No Ordinary Sun was published by Blackwood and Janet Paul in September 1964. In September 2008, it is an understatement to say that New Zealand Māori literature in English has spread beyond its national boundaries, and that many writers, Māori and non-Māori, stand on Tuwhare‘s shoulders (―Hone Tuwhare‘s Aroha‖ Hone Tuwhare Special Issue:Ka Mate Ka Ora: A New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics, p4). Tuwhare‘s life and poetry are celebrated in a Special Issue of Ka Mate Ka Ora: A New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics and by an extended tribute to ―An Extraordinary Poet‖ by Robert Sullivan in Kunapipi: Journal of Postcolonial Writing. -

View Complete Text Here

1 The celebrated poet Eileen Duggan and the influential editor J H E Schroder were among the early appreciators of Niel Wright’s verse. This selection draws on six decades of writing, 120 Books of Wright’s epic poem The Alexandrians as well as his Post-Alexandrian work, and displays an extraordinary and wide-ranging talent. Avoiding the narrow constraints of a regionalist poetry or the bohemian outlook of the Wellington group of poets, Wright has consistently forged his own path and poetic style since the 1950s often at odds with contemporary fashion and modernist/postmodernist tendencies. As with the English poet Robert Bridges, he has sought above all to renew the prosody. Skilled in many traditional forms such as the triolet, the epigram, the ballad, the ode, the sonnet and the lyric as well as classical and epic narrative verse, the selection presents for the first time a generous sampling of his prolific output and reveals his original and remarkable voice in New Zealand poetry. … a delight to see the classics revived in a comparatively new land and in an age alien to them. – Eileen Duggan, personal correspondence … a witty turn of phrase … – James K Baxter, New Zealand Listener … a poet of unusual range … Mr Wright’s use of prosody and his use of half-rhymes and assonances often recall those of Wilfred Owen. – Peter Dronke, Landfall … a pot-pourri of astonishing richness, lyrical in its presentation but with a strong narrative thread. – Michael Gifkins, New Zealand Listener 2 THE POP ARTISTS GARLAND Frank William Nielsen Wright was born in Sydenham, Christchurch, in 1933 and educated at Christchurch Boys High School and Canterbury University and Victoria University of Wellington (where he was awarded his PhD in 1974).