Insolvency in German Football and Find That It Occurs at a Frequency Comparable to Leagues in England and France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infoblättsche #13 – FSV Frankfurt

| Infoblättsche Kurvenorgan der Generation Luzifer 1998 25. Spieltag • Samstag, 06.03.2010 • FCK - FSV Frankfurt • IB Nr. 13 Saison 2009/10 • FCK - FSV Frankfurt IB Nr. 25. Spieltag • Samstag, 06.03.2010 | Editorial Vorschau Zweite Bundesliga Sonntag, 14.03.10, 13:30 Uhr: FCK - Cottbus [Dön] Hallo zusammen! Montag, 22.03.10, 20:15 Uhr: F. Düsseldorf - FCK Doppelderbysieger! Mit diesem kurio- Montag, 29.03.10, 20:15 Uhr: FCK - 1860 München sen und stolzen Titel darf sich unser Ver- ein nach dem vergangenen Wochenende Regionalliga West schmücken, an welchem mit Karlsruhe und Mannheim gleich zwei Erzrivalen ge- Samstag, 13.03.10, 14:00 Uhr: FCK II - FSV Mainz 05 putzt wurden. Der wichtigere der beiden Samstag, 20.03.10, 14:00 Uhr: Bayer II - FCK II Siege war natürlich jener im Wildpark, durch welchen wir nun wieder sechs Punkte auf unseren ärgsten Verfolger, ak- tuell Augsburg haben. Der große Traum vom Aufstieg, er rückt immer näher! Heute nun starten die beiden Heimspiel- wochen, in denen wir mit Heimsiegen ge- gen die vermeintlich schwächeren Geg- ner FSV Frankfurt und Cottbus weitere wichtige Grundvoraussetzungen für den Tabelle: (Stand 04.03.10) Gang in Deutschlands Beletage schaffen können. Doch das Spiel gegen Ahlen ist 1. 1.FC Kaiserslautern 40:18 53 jedem noch im Hinterkopf, habt heute 2. FC Augsburg 48:28 47 also Geduld mit unserer Mannschaft, 3. FC St. Pauli 48:25 46 wenn es nicht gleich von Anfang an spie- 4. Fortuna Düsseldorf 37:22 43 lerisch zum Besten steht. Neben einer 5. Arminia Bielefeld 36:23 43 vermutlich defensiven Spielweise der 6. -

DSFS Bundesliga-Chronik 1965/66 2

DSFS Bundesliga-Chronik 1965/1966 Alle wichtigen Daten der Saison: Tabellen, Ergebnisse, Einsätze, Tore, Platzverweise, Elfmeter. Deutscher Sportclub für Fußballstatistiken e. V. DSFS Bundesliga Chronik 1965/66 1 Die Schützen und Torhüter bei Elfmetern sind zunächst nach der Inhalt Anzahl erfolgreicher Aktionen und anschließend nach der geringe- ren Anzahl der nicht erfolgreichen Aktionen sortiert. Dabei gelten Tabelle und Ergebniskasten …………………………………… 2 im Nachschuss erzielte Treffer immer als verschossene Elfmeter. Spezialtabellen ………………………………………….………. 3 Termine und Ergebnisse aller Spieltage ……………………... 4 Da in der Saison 1965/66 die gelben und roten Karten noch nicht Torschützen- und Elfmeterstatistiken ………………………… 6 eingeführt waren und die meisten Mannschaften die Saison auch Platzverweis-, Zuschauer-, Schiedsrichterstatistik usw. ……. 7 ohne einen Platzverweis beendeten, sind nur die Mannschaften Die Kader und alle Spiele der Mannschaften: und Spieler mit einem Platzverweis aufgeführt. SC Tasmania 1900 Berlin …...……………..…………… 8 Die Liste der jüngsten und ältesten Spieler und Mannschaften Eintracht Braunschweig ……………………...………….. 10 bezieht sich jeweils auf einzelne Spiele, nicht auf den Durchschnitt SV Werder Bremen ………………………..…………….. 12 der Saison. Borussia Dortmund ………………………………………. 14 Bei den Zuschauerzahlen wurden jeweils die geringeren Zahlen SG Eintracht Frankfurt …………………………..………. 16 aus zwei unterschiedlichen Quellen angegeben, da auch die sich Hamburger SV ……………………………………………. 18 hieraus ergebende Gesamtzahl von 7.421.697 Zuschauern -

2. Bundesliga

2. Bundesliga Mit dem Beschluss auf dem Bundestag des Deutschen Fußball-Bundes Im Folgejahr gab es eine Mammutsaison mit 24 Vereinen bei 46 am 7. Juni 1980 in Düsseldorf wurde die 2. Bundesliga als bundesweit Spieltagen und sieben Absteigern. Im letzten Schritt erfolgte die eingleisige zweite Spielklasse des DFB zur Spielzeit 1981/82 eingeführt. Reduzierung der 2. Bundesliga von 20 auf 18 Vereine. Die ersten Zwei der Tabelle steigen am Ende der Saison auf, die letzten Zwei steigen ab. Sie folgte der 2. Liga Nord und Süd, die 1974 nach Neuordnung des Spielsystems und Einführung eines Lizenzspielerstatuts, mit je 20 Die Relegation zwischen 2. Bundesliga und BUNDESLIGA gab es von Vereinen als Spielklasse der fünf Regionalverbände agierte. Die hatte 1981/82 bis 1990/91 und dann wieder ab der Saison 2008/09. Nach die vorherigen fünf Regionalligen mit gesamt 90 Vereinen abgelöst. Gründung der 3. Liga als bundesweite oberste Spielklasse des DFB spielen der drittletzte der 2. Bundesliga und der dritte der 3. Liga Die Premierensaison nahmen 20 Vereine auf, die zuvor ebenfalls eine Relegation. zulassungsrelevante technische und sportliche Qualifikationskriterien zu erfüllen hatten. Der FC Schalke 04 wurde der erste Meister der Mit Beschluss des außerordentlichen DFB-Bundestags in Mainz am 30. neuen Zeitrechnung, auch Vizemeister Hertha BSC Berlin stieg direkt in September 2000 wurden die 36 Profiklubs in die von ihnen seit vielen die BUNDESLIGA auf. Jahren geforderte Selbstständigkeit entlassen. Ab 2001 liegt die 2. Bundesliga in der Zuständigkeit des DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga GmbH. Nach der deutschen Wiedervereinigung galt es, Vereine aus dem Sie führt das operative Geschäft des „Die Liga - Fußballverband e.V.“, Nordostdeutschen Fußballverband (NOFV) als Clubs aus der den Zusammenschlusses der lizenzierten Vereine und ehemaligen DDR zu integrieren. -

Der Besessene Will Weiter Vollgas Geben Benno Mohr Aus Saarbrücken Wurde in Mönchengladbach Ausgebildet

D2 Sport DONNERSTAG, 27. APRIL 2017 SERIE SAARLÄNDER IM PROFIFUSSBALL, TEIL 11 Der Besessene will weiter Vollgas geben Benno Mohr aus Saarbrücken wurde in Mönchengladbach ausgebildet. Im Sommer will er woanders den nächsten Schritt machen. VON TOBIAS FUCHS sehen. Alles so nah und doch un- mit der Saarbrücker U19 in der aber zum Cheftrainer in der Bun- erreichbar. Bundesliga. Da war er, in Worten: desliga befördert. Klar ist: Nicht SAARBRÜCKEN Benno Mohr hatte Das Interview findet mitten in fünfzehn. Einer seiner Trainer alles lief gut für Mohr. Doch er am Wochenende spielfrei. Also Saarbrücken statt, in einem Café flachste, er sehe in ihm einen sagt: „Ich suche keine Ausreden.“ fuhr er nach Hause ins Saarland. am St. Johanner Markt. Mohr be- zweiten Patrick Herrmann – mit Der 1. FC Saarbrücken wollte Am Samstag schaute sich Mohr stellt Mineralwasser, ein Getränk besserer Technik. ihn in der Winterpause verpflich- den 1. FC Saarbrücken an. In Völk- für Sportler und Realisten. Er be- Wenn er auf diese Zeit zurück- ten. Mohr konnte sich einen lingen gegen die SV Elversberg. richtet von seinem Leben als Profi, blickt, spricht Mohr von einem Wechsel vorstellen. „Nach wie vor Tags drauf kickte er auf dem Ro- unaufgeregt, trotz unsicherer Per- „brutalen Leistungsschub“, den er liebe ich die Stadt und auch den denhof, mit Dutzenden anderen, spektive. Im Moment kann Mohr sich bis heute nicht erklären kann. Verein.“ Er ist Mitglied, seit 2003. wie früher. Anfang der Woche seinen Sport ein wenig von außen Schließlich wechselte er nach Doch Gladbach brauchte einen kehrte der 21-Jährige zurück nach betrachten. -

1996: Zweiter Beim NOFV-Hallenchampionat

1996: zweiter beim NOFV-HalleNcHampiONat Im Dezember 1996 veranstaltete der Nordostdeutsche Fußballverband (NOFV) seine erste Hallen- meisterschaft. Er wurde im November 1990 gegründet, nachdem sich der Deutsche Fußball-Ver- band (DFV) der DDR kurz zuvor aufgelöst hatte. Die Premiere des Hallenchampionats wurde drei Tage vor Silvester 1996 in der Magdeburger Hermann-Gieseler-Halle ausgetragen. „Fußball muss populär bleiben. Mit dem Veltins-Cup wollten wir auf uns aufmerksam machen. Das ist gelungen”, so der damalige NOFV-Präsident Dr. Hans-Georg Moldenhauer nach einer Ver- anstaltung, die voller Überraschungen war. Im Vorfeld als Hochkaräter gehandelte Mannschaften wie FC Rot-Weiß Erfurt, Chemnitzer FC oder SG Dynamo Dresden waren schon in den drei Quali- fikationsturnieren zuvor gescheitert. So dachten viele, dass der souveräne Regionalliga-Nordost- Spitzenreiter und DFB-Pokal-Halbfinalist FC Energie Cottbus mit Trainer „Ede” Geyer der Favorit sein würde. Pustekuchen: Die Veilchen aus Aue und der FSV Velten kamen ins Endspiel. Die Idee des NOFV, ein Hallenturnier in der Winterpause 1996/97 auszutragen, fand von allen Seiten Lob. Immerhin musste der Verband intensiv auf Sponsorensuche gehen, um den rund 470.000-DM-Etat zu sichern. In drei Vorrundenturnieren (Brandenburg, Lößnitz und Senftenberg) wurden am 3. Adventswochenende 1996 die sechs Endrundenteilnehmer ausgespielt. Gerade das Turnier in Lößnitz erhielt wegen der guten Organisation seitens des FC Erzgebirge Aue und der tollen Atmosphäre in der Erzgebirgshalle Anerkennnung. Ohne Niederlage erreichten die Veilchen das Halbfinale nach Erfolgen über den Dresdner SC (2:0), 1. Suhler SV (3:0) und Wacker Nordhausen (5:2). Höhepunkt war dann das Duell der ersten Halbfinalpaarung zwischen Aue und dem Chemnitzer FC. -

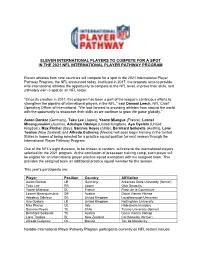

Eleven International Players to Compete for a Spot in the 2021 Nfl International Player Pathway Program

ELEVEN INTERNATIONAL PLAYERS TO COMPETE FOR A SPOT IN THE 2021 NFL INTERNATIONAL PLAYER PATHWAY PROGRAM Eleven athletes from nine countries will compete for a spot in the 2021 International Player Pathway Program, the NFL announced today. Instituted in 2017, the program aims to provide elite international athletes the opportunity to compete at the NFL level, improve their skills, and ultimately earn a spot on an NFL roster. “Since its creation in 2017, this program has been a part of the league’s continuous efforts to strengthen the pipeline of international players in the NFL,” said Damani Leech, NFL Chief Operating Officer of International. “We look forward to providing athletes from around the world with the opportunity to showcase their skills as we continue to grow the game globally.” Aaron Donkor (Germany), Taku Lee (Japan), Yoann Miangue (France), Leonel Misangumukini (Austria), Adedayo Odeleye (United Kingdom), Ayo Oyelola (United Kingdom), Max Pircher (Italy), Sammis Reyes (Chile), Bernhard Seikovits (Austria), Lone Toailoa (New Zealand) and Alfredo Gutierrez (Mexico) will soon begin training in the United States in hopes of being selected for a practice squad position for next season through the International Player Pathway Program. One of the NFL's eight divisions, to be chosen at random, will receive the international players selected for the 2021 program. At the conclusion of preseason training camp, each player will be eligible for an international player practice squad exemption with his assigned team. This provides the -

Stadionheft Landesklasse Ost | Saison 2016/17 | Ausgabe 04 | April 2017

Stadionheft Landesklasse Ost | Saison 2016/17 | Ausgabe 04 | April 2017 FV Dresden 06 versus Bischofswerdaer SV II PRÄSENTIERT VON: HOGA SCHULEN DRESDEN - EINE STARKE GEMEINSCHAFT www.hoga-schulen.de Hotelmanagementschule HOFA mit BA in Tourismusmanagement IHK-GEPRÜFTE AUSBILDUNG AUSLANDSPRAKTIKUM BACHELOR OF ARTS Info-Tag | 10.06.2017 | 10 bis 14 Uhr Zamenhofstr. 61/63, Dresden ANSTOSS VORWORT Liebe Sportfreundinnen und Sportfreunde, zum Heimspiel gegen Oberland Spree hatten wir unerwarteten Besuch. Die Jungs von „so‘n Hafer“ kamen zur Stippvisite an die Steirische Straße. So‘n Hafer ist eine kleine Facebook- bzw. Blog-Community, die Woche für Woche große und kleine Vereine besucht und ihre Erlebnisberichte zum Spiel und andere Beobachtungen publiziert. Sympathisch und mit viel Wortwitz findet man die Berichte dann kurze Zeit später online. Die Jungs bewerteten besonders unsere Anlage als modern und das Drumherum als ansprechend. Neben dem Funktionsgebäude wurden auch das Stadionheft und die Plätze gelobt. Die Sanitäranlagen wurden als überdurchschnittlich hervorgehoben, auch wenn sie für den Geschmack der Autoren etwas zu weit weg liegen. Dieses Lob aus berufenem Munde freut uns ungemein, wird doch oft vergessen, dass wir nur ein Peter Stein, Präsident kleiner Dresdner Verein sind, der versucht seinen Mitgliedern schöne Rahmenbedin- gungen zu bieten. Auch unser Mann am Mikrofon – Helmut Rinke – wird positiv bewertet. Den Kritikpunkt der fehlenden Halbzeitfolklore haben wir notiert und be- IMPRESSUM sprechen es im Vorstand. Ein tolles Lob ging auch an die Familie Opitz, deren Stadi- onwurst als „sensationell“ beschrieben wurde. Die Jungs hätten zwar gern noch Fisch- Herausgeber: FV Dresden 06 Laubegast e.V. semmeln im Angebot gesehen, aber auch die Bierpreise wurden als fair eingeschätzt. -

Footballers with Migration Background in the German National Football Team

“It is about the flag on your chest!” Footballers with Migration Background in the German National Football Team. A matter of inclusion? An Explorative Case Study on Nationalism, Integration and National Identity. Oscar Brito Capon Master Thesis in Sociology Department of Sociology and Human Geography Faculty of Social Sciences University of Oslo June 2012 Oscar Brito Capon - Master Thesis in Sociology 2 Oscar Brito Capon - Master Thesis in Sociology Foreword Dear reader, the present research work represents, on one hand, my dearest wish to contribute to the understanding of some of the effects that the exclusionary, ethnocentric notions of nationhood and national belonging – which have characterized much of western European thinking throughout history – have had on individuals who do not fit within the preconceived frames of national unity and belonging with which most Europeans have been operating since the foundation of the nation-state approximately 140 years ago. On the other hand, this research also represents my personal journey to understand better my role as a citizen, a man, a father and a husband, while covered by a given aura of otherness, always reminding me of my permanent foreignness in the country I decided to make my home. In this sense, this has been a personal journey to learn how to cope with my new ascribed identity as an alien (my ‘labelled forehead’) without losing my essence in the process, and without forgetting who I also am and have been. This journey has been long and tough in many forms, for which I would like to thank the help I have received from those who have been accompanying my steps all along. -

Mirco Born Darmstadt & Balingen Der Fc-Astoria Aus

DAS SPIELTAGSMAGAZIN DES FSV FRANKFURT FSV#10 Saison 19/20 FC-Astorialife Walldorf IM INTERVIEW: MIRCO BORN IM RÜCKBLICK: DARMSTADT & BALINGEN IM VISIER: DER FC-ASTORIA AUS WALLDORF FSVlife #10 Saison 19/20 2 Samstag, 30.11.2019 FC-Astoria Walldorf LIEBE FREUNDE, ANHÄNGER, PARTNER UND MITGLIEDER DES FSV FRANKFURT! Ich begrüße Sie recht herzlich in der PSD Bank Arena zu unserem letzten Heimspiel in die- sem Jahr. Mit dem FC-Astoria Walldorf kommt am 2. Rückrundenspieltag der aktuell Tabel- lensechste an den Bornheimer Hang, der aller- dings sechs der sieben letzten Ligaspiele nicht gewinnen konnte. Am vergangenen Samstag hat unsere Mann- schaft in Balingen mit dem 4:1 Sieg einen wichtigen Schritt hinsichtlich dem Anschluss an die obere Tabellenhälfte gemacht. Schon ein paar Tage zuvor im Testspiel gegen den Zweitligisten SV Darmstadt 98 haben unsere Jungs gezeigt, dass wir auf dem richtigen Weg sind, unser Saisonziel zu erreichen. Wir hatten uns nach der guten Vorbereitung im Sommer mit durchaus beachtenswerten Ergebnissen vorgenommen, schon sehr frühzeitig nichts Am vergangenen Dienstag fand im Business mit den Abstiegsrängen zu tun haben zu wol- Bereich der PSD Bank Arena die Jahreshaupt- len. Und der Auftritt in Balingen zeigt, dass wir versammlung des FSV Frankfurt 1899 e.V. auf dem richtigen Weg sind. Nimmt man den statt. Dabei hatte ich die Gelegenheit, den Testspielsieg und den Sieg im Hessenpokal zahlreich erschienenen Mitgliedern einen gegen die SG Waldsolms hinzu, ist unser FSV Überblick über die verschiedenen Aktivitä- nun schon seit 7 Spielen ungeschlagen. Ich ten in den unterschiedlichen Bereichen des bin fest davon überzeugt, dass wir diese Serie Vereins zu geben. -

Building for Emotions Contents 01 02 03

BAM Sports – Building for Emotions Contents 01 02 03 01 Gellertstraße Stadium, Chemnitz 02 Continental Arena, Regensburg 03 Hazza bin Zayed Stadium, Al Ain 04 First Direct Arena, Leeds 05 Schwalbe Arena, Gummersbach 06 King Abdullah Sports Stadium, Jeddah 08 09 10 07 Coface Arena, Mainz 08 Nelson Mandela Stadium, Port Elizabeth 09 FNB Stadium, Johannesburg 10 Rudolf Harbig Stadium, Dresden 11 SGL Arena, Augsburg 12 O2 World, Berlin 13 Rittal Arena, Wetzlar 14 MHP Arena, Ludwigsburg 15 HDI Arena, Hanover 15 16 17 16 DKB Arena, Rostock 17 Veltins Arena, Gelsenkirchen 18 Gelredome, Arnheim 19 De Kuip, Rotterdam 20 Philips Stadium, Eindhoven 04 05 06 07 11 12 13 14 18 19 20 01 Good timing was called for: BAM Sports was One particularly conspicuous detail of this Country: Germany Gellertstraße appointed general contractor for the recon- project is the façade of the new main build- struction work on Chemnitz football stadium, ing, which is surrounded by a blue metal band. Type: Stadium which no longer met the standards for a mod- Reminiscent of a football scarf draped casually Stadium ern ground. The need to build the new stadium around the shell, this band leaves no one in any Seating: 8,274 mid-way through the season was a particularly doubt about who rules the roost here – Chem- Chemnitz daunting challenge that has developed into nitzer FC, the “Sky Blues”. At long last, the new Standing areas: 6,000 a core competency of BAM Sports. The old stadium also has an exclusive business area stands were demolished and re-erected one at with 800 seats and 12 boxes. -

Braunschweig – Karlsruher SC Fotos: Robin Koppelmann Reger Gut, Gab Es Diesmal Nicht Vereinen Grundsätzlich in Frage Einmal an Den Würstchen Mit Stellen

Fan-News Atmosphäre Hamburg JHV-TOP Stadionverbote Die ordentliche Mitgliederver- Verhältnismäßigkeit zu überprü- sammlung 2005 beim Ham- fen. Hiermit zusammenhängend burger Sport-Verein e.V. verlief möge der Vorstand, so Lieb- harmonisch wie selten. Waren nau, auch die im Lizenzvertrag Veranstaltungen dieser Art in der DFL festgesetzte Praxis zur der Vergangenheit grundsätzlich Durchsetzung der Stadionverbo- für den einen oder anderen Auf- te zukünftig bei DFL und anderen Eintracht Braunschweig – Karlsruher SC Fotos: Robin Koppelmann reger gut, gab es diesmal nicht Vereinen grundsätzlich in Frage einmal an den Würstchen mit stellen. Dieser Aufruf, die Sta- Kartoffelsalat etwas auszuset- dionverbote erst für den eigenen zen. Das mag neben dem sport- Hausrechtsbereich zu prüfen, Klare Worte unter der Rubrik „Verschiedenes“: Jojo Liebnau Foto: hsv-supporters.de lichen Erfolg auch am Fehlen verwundert nicht, ist Liebnau des als streitbar bekannten Ex- doch selbst Mitglied der Fan- von Runge der Auftrag an den stand des HSV werde sich zu- Präsidenten Dr. Peter Krohn ge- gruppierung „Chosen Few“ und Vorstand, Stadionverbote von sammensetzen und über die legen haben. So kam es, dass über die teils zweifelhaften Ver- HSV-Mitgliedern mittels Anhö- Möglichkeiten in dieser Richtung die Versammlung bereits um gabepraktiken wohl informiert. rung des Ehrenrates überprüfen beraten, so Reichert. 20:15 Uhr dem Tagesordnungs- Bemerkenswert ist jedoch, dass zu lassen. Denn laut Vereinssat- Hierin mag zwar zunächst nur punkt „Verschiedenes“ zuging. Liebnaus Aufruf vom Ehren- zung des HSV e.V. hat allein der ein vorsichtiges Entgegenkom- Hier betrat Jojo Liebnau, Beisit- ratsvorsitzenden des HSV und Ehrenrat über mögliche Verfeh- men in Richtung der Mitglieder Eintracht Braunschweig II – Hannover 96 II Foto: Robin Koppelmann zer der Abteilungsleitung För- Rechtsanwalt, Claus Runge, un- lungen eines Vereinsmitgliedes – vorbehaltlich von Regelungen dernde Mitglieder /Supporters terstützt wurde. -

GFL Kalender 36

Nr. 33/19 13.08.2019 www.football-aktuell.de eHUDDLE 33/19 13. August 2019 GFL Kalender 36 Mercenaries können Comets nicht stoppen 3 NFL Zehnte Südmeisterschaft gesichert 4 Quinns Agent meckert 38 Lions Bollwerk hält gegen Dresden 6 Kritik an der NFL 38 Kiel reduziert Hildesheim auf 21 Punkte 8 Eagles verlieren und verlieren Backup-QB 39 Dukes zähmen Wildkatzen erneut 10 Erfolgreiches Debüt 40 Sieg nach Puntfestival 12 Broncos verpflichten Ex-Lion Riddick 40 GFL 2 St.-Brown-Touchdown leitet Sieg ein 42 Die Kritiker verstummen lassen 42 Fans und Head Coach sind begeistert 15 Ein Blick in die Zukunft 43 Paladins auch im zweiten Derby sieglos 16 Neue Männer braucht New England 43 Viel Arbeit für Detroit 43 Griffins müssen sich geschlagen geben 18 Kasim Edebalis siebte Station 44 Komfortable Situation für Elmshorn 19 Ein neuer Cornerback für die Chiefs 44 Regionalligen NFL Flag Football in Hamburg 45 Neuzugang mit gebrochener Hand 45 Oldenburg lässt Chancen ungenutzt 23 Angriff der Chiefs schon wieder in Fahrt 46 News Ein Corner statt eines Receivers 46 Invaders rüsten für Spitzenspiel 23 Wenig Aussagekraft auf beiden Seiten 47 McLaurin überzeugt 47 Meisterschaft nach Aufholjagd 24 Steelers starten mit Sieg in Preseason 48 Saisonfinale im Deutschordenstadion 25 Ravens mit bekannter Formel zum Sieg 48 Invaders zum ersten Mal in GFL-Playoffs 26 Browns in großartiger Frühform 49 U19 verpasst den Junior Bowl 26 Texans verstärken Backfield 49 Wiesbaden gewinnt Halbfinale in Berlin 27 Das Tight End-Projekt ist gescheitert 50 Schweden ringt Britannien