Gettin' Down Home with the Neelys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Plan, a List of Important Kpis, a Line Budget, and a Timeline of the Project

Sierra Marling PRL 725 Come Together Campaign Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 2 Transmittal Letter ................................................................................................................... 3 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Situation Analysis .................................................................................................................. 7 Stakeholders .......................................................................................................................... 8 SWOT Analysis ....................................................................................................................... 9 Plan ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Key Performance Indicators ................................................................................................... 17 Budget .................................................................................................................................. 20 Project Timeline (Gantt)......................................................................................................... 21 References ............................................................................................................................ -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

La Pornografía En Los Tiempos Del Coronavirus

La pornografía en los tiempos del coronavirus NIEVES PASCUAL Universidad Internacional de Valencia Resumen El presente ensayo investiga el regalo que el 24 de marzo de 2020 el sitio pornográfico Pornhub ofrece a los usuarios como entretenimiento durante el confinamiento por el coronavirus. Investiga las razones públicas de este presente y el incremento en el consumo de porno que se produce a raíz del aburrimiento que genera la cuarentena. Propone que si bien Pornhub procura protegernos del COVID-19, la reciprocidad a la que nos obliga su obsequio no es simétrica. Palabras claves: pornografía, Pornhub, regalo, adicción, epidemia Abstract This essay investigates the gift that on March 24, 2020, the pornographic site Pornhub offers users as entertainment during the confinement due to the Coronavirus. It investigates the public reasons motivating the gift, and the increase in porn consumption caused by the boredom generated by the quarantine. It proposes that while Pornhub may intend to help protect consumers from COVID-19, the reciprocity its gift obliges us with is not symmetrical. Key words: pornography, Pornhub, gift, addiction, epidemic Junto a Bongacams, Chaturbate, Redtube y Xhamster, Pornhub.com, calificado en las redes como “el sitio web de porno más grande del mundo”, se sitúa entre los cinco portales pornográficos de más audiencia a nivel global. El 17 de marzo de 2020 Pornhub regalaba su contenido Premium en España para ayudar a entretenernos durante la cuarentena por el coronavirus. “¡Vamos, España!”, se leía en la página de inicio. Sobre el fondo de un mapa tricolor del país y la figura de una gitana enarbolando su abanico, el mensaje, en <https://es.pornhub.com>, era el siguiente: En vista de la expansión de las cuarentenas, estamos extendiendo el acceso gratuito a Free Pornhub Premium para este mes a nuestros amigos de España, y así ayudar a pasar el tiempo y mantenernos entretenidos. -

See You Later

FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 15, 2018 5:42:00 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of December 23 - 29, 2018 Busy Philipps hosts “Busy Tonight” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 See you •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 later The battle for late-night dominance continued in 2018 with new hosts, new shows, new formats and surprising turnarounds in ratings. TBS announced that “Conan” would undergo some serious format changes designed to retain its young audience and pull in new viewers from the digital generation, while actress and social media sensation Busy Philipps (“Dawson’s Creek”) began hosting her new late-night vehicle, “Busy Tonight,” on E! WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE To advertise here ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE please call 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE1 x 3” (978) 946-2375 We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC INSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 15, 2018 5:42:02 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 CHANNEL Kingston Sports Highlights Atkinson Londonderry EFC 47 Brendon Katz vs. Sizwe 12:30 p.m. (8) Soccer EPL Arsenal Boston Celtics at Memphis Grizzlies Salem Sunday Sandown Windham Mnikathi at Liverpool Liverpool, England Live Memphis, Tenn. -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

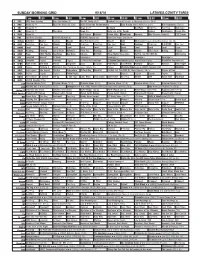

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER What national organization was founded on President National Association for the Arts Advancement of Colored People (or Lincoln’s Birthday? NAACP) 2 In 1905 the first black symphony was founded. What Sports Philadelphia Concert Orchestra was it called? 3 The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in what Sports 1852 4 year? Entertainment In what state is Tuskegee Institute located? Alabama 5 Who was the first Black American inducted into the Pro Business & Education Emlen Tunnell 6 Football Hall of Fame? In 1986, Dexter Gordan was nominated for an Oscar for History Round Midnight 7 his performance in what film? During the first two-thirds of the seventeenth century Science & Exploration Holland and Portugal what two countries dominated the African slave trade? 8 In 1994, which president named Eddie Jordan, Jr. as the Business & Education first African American to hold the post of U.S. Attorney President Bill Clinton 9 in the state of Louisiana? Frank Robinson became the first Black American Arts Cleveland Indians 10 manager in major league baseball for what team? What company has a successful series of television Politics & Military commercials that started in 1974 and features Bill Jell-O 11 Cosby? He worked for the NAACP and became the first field Entertainment secretary in Jackson, Mississippi. He was shot in June Medgar Evers 12 1963. Who was he? Performing in evening attire, these stars of The Creole Entertainment Show were the first African American couple to perform Charles Johnson and Dora Dean 13 on Broadway. -

Daryl Hall and William Shatner to Join Diy Network’S Celebrity Roster in 2014

DARYL HALL AND WILLIAM SHATNER TO JOIN DIY NETWORK’S CELEBRITY ROSTER IN 2014 NEW YORK (For Immediate Release—April 1, 2014) From celebrities tackling home remodels to regular folks renovating their homes, DIY Network will premiere seven new series that focus on the realities of home improvement. The network’s latest addition to its “celebrity home rehab” franchise, The Shatner Project, premieres in October and will follow the home renovation of actor William Shatner, instantly recognizable to television fans as the original Star Trek captain, James T. Kirk, commander of the starship U.S.S. Enterprise; Sergeant T.J. Hooker of T.J. Hooker and Attorney Denny Crane of Boston Legal. In July, the highly anticipated series, Daryl’s Restoration Over-Hall will premiere, starring singer/songwriter Daryl Hall from the musical duo Hall & Oates as he revives the historic charm of an 18th century Connecticut home. In addition, popular licensed contractor Jason Cameron will help homeowners smash their way to gorgeous new spaces by wrecking and remodeling their worst rooms in the new series, Sledgehammer. “DIY Network offers an authentic look at the realities of dealing with any home improvement project,” said Steven Lerner, senior vice president of programming development, HGTV and DIY Network. “When fans see Daryl Hall chasing his passion for historical rehab or William Shatner remodeling his outdated LA pad, they’re getting a glimpse of a real renovation – and they’re seeing that no matter who you are, the challenges that come with tackling a home remodel are universal.” Additional new DIY Network series will include First Time Flippers featuring overzealous property virgins who put their do-it-yourself real estate skills to the ultimate test and Stone Age which follows father and son duo, Steve and Nick Rhule, as they build amazing custom outdoor designs, including waterfalls, patios and fire pits, one rock at a time. -

P25-26 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2017 TV PROGRAMS 20:12 The Jim Gaffigan Show Cat Noir 03:20 Celebrity Style Story 17:40 Mountain Men 14:36 The Thundermans 23:15 Sunday, Bloody Sunday 20:35 Kroll Show 22:20 Miraculous Tales Of Ladybug And 03:50 Hollywood & Football 18:30 Swamp People 15:00 Henry Danger 21:00 The Daily Show With Trevor Noah Cat Noir 04:40 Hollywood & Football 19:20 Mountain Men 15:24 The Loud House 21:30 The Half Hour 22:45 Lolirock 05:30 Celebrity Style Story 20:10 American Pickers 15:48 SpongeBob SquarePants 22:00 Tosh.0 23:05 Disney Mickey Mouse 06:00 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 21:00 Counting Cars 16:12 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 00:35 Revenge Of The Green Dragons 22:25 Tosh.0 23:10 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage Henry 21:25 Counting Cars 16:36 The Loud House 02:10 Harlock: Space Pirate 22:50 Idiotsitter Witch 06:55 E! News 21:50 Forged In Fire 17:00 Regal Academy 04:00 In The Heart Of The Sea 23:15 The Alternative Comedy 23:35 Binny And The Ghost 07:10 Hollywood Medium With Tyler 22:40 Forged In Fire 17:24 Winx Club 00:25 Mia And The Migoo 06:00 X-Men: First Class Experience Henry 23:30 American Pickers 17:48 Hunter Street 02:05 Ploddy Police Car On The Case 08:10 Harlock: Space Pirate 23:40 The Daily Show With Trevor Noah 08:10 E! News: Daily Pop 18:12 Henry Danger 03:25 Memory Loss 10:05 The Darkest Hour 09:10 WAGs Miami 18:36 Nicky, Ricky, Dicky & Dawn 04:50 Big Baby 11:45 In The Heart Of The Sea 10:10 WAGs Miami 19:00 School Of Rock 06:20 Mia And The Migoo 13:50 X-Men: First Class 11:05 WAGs Miami 19:24 Game Shakers 08:00 -

Guy Fieri Sends Superstar Chefs Racing Through the Aisles in Guy's Grocery Games All-Stars

Press Contact: Ginger Chan P: 323-330-8863; [email protected] GUY FIERI SENDS SUPERSTAR CHEFS RACING THROUGH THE AISLES IN GUY'S GROCERY GAMES ALL-STARS Five Episode Stunt Premieres August 23rd at 8pm ET/PT on Food Network NEW YORK – July 20, 2015 - Guy Fieri hosts some of the biggest stars from Food Network and Cooking Channel in special summertime stunt, Guy’s Grocery Games All-Stars, premiering Sunday, August 23rd at 8pm ET/PT on Food Network. Each of the five episodes features four culinary all-stars competing in a number of challenges as they navigate their way through the aisles of a grocery store with curveballs from games such as the Fieri Food Pyramid and the feared Food Wheel. Whether it is preparing an upscale dinner using frozen and canned foods, making a noodle dish from the clearance carts or creating a dinner using ingredients from the produce aisle only, each All-Star chef has to shop, prepare, and plate three different dishes using only what they can grab from the grocery store aisles. One-by-one the losing All-Stars check out, determined by a rotating panel of judges that includes Richard Blais, Melissa d’Arabian, Duskie Estes, G. Garvin, Troy Johnson, Beau MacMillan, Brian Malarkey, Catherine McCord and Aarti Sequeira. In the fifth and final episode, each All-Star is teamed up with a professional athlete, giving them even more of a sporting chance to be the victor and go on a shopping spree for a cash prize for their charity! Fans can head to FoodNetwork.com/GroceryGames to relive video and photo highlights, take quizzes and much more. -

P32 Layout 1

TV PROGRAMS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2013 10:30 On The Case With Paula Zahn 11:20 Solved 12:10 Disappeared 13:00 Mystery Diagnosis 03:25 Queens Of The Savannah 03:00 The Hairy Bikers Ride Again 13:50 Street Patrol 04:15 Snow Leopards Of Leafy 03:30 Fantasy Homes By The Sea 14:15 Street Patrol 03:00 The Suite Life Of Zack & Cody London 04:20 The Boss Is Coming To Dinner 14:40 Forensic Detectives 03:20 The Suite Life Of Zack & Cody 04:40 Snow Leopards Of Leafy 04:45 Cash In The Attic 15:30 On The Case With Paula Zahn 03:45 Sonny With A Chance London 05:30 Raymond Blanc’s Kitchen 16:20 Real Emergency Calls 04:05 Sonny With A Chance 05:05 North America Secrets 16:45 Who On Earth Did I Marry? 04:30 Suite Life On Deck 05:55 Animal Kingdom 05:55 Bargain Hunt 17:10 Disappeared 04:50 Suite Life On Deck 06:20 Lion Man: One World African 06:40 Fantasy Homes By The Sea 18:00 Solved 05:15 Wizards Of Waverly Place Safari 07:30 The Boss Is Coming To Dinner 18:50 Forensic Detectives 05:35 Wizards Of Waverly Place 06:45 Animal Airport 08:00 Extreme Makeover: Home 19:40 On The Case With Paula Zahn 06:00 Austin And Ally 07:10 Animal Airport Edition 21:20 Nightmare Next Door 06:25 Austin And Ally 07:35 Call Of The Wildman 08:45 Bargain Hunt 22:10 Couples Who Kill 06:45 A.N.T. -

2011/2012 Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions # CATEGORY

2011/2012 Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions # CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER Along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, what type of music is played 1 Arts with the accordion? Zydeco 2 Arts Who wrote "Their Eyes Were Watching God" ? Zora Neale Hurston Which one of composer/pianist Anthony Davis' operas premiered in Philadelphia in 1985 and was performed by the X: The Life and Times of 3 Arts New York City Opera in 1986? Malcolm X Since 1987, who has held the position of director of jazz at 4 Arts Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York City? Wynton Marsalis Of what profession were Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Countee Cullen, major contributors to the Harlem 5 Arts Renaissance? Writers Who wrote Clotel , or The President’s Daughter , the first 6 Arts published novel by a Black American in 1833? William Wells Brown Who published The Escape , the first play written by a Black 7 Arts American? William Wells Brown 8 Arts What is the given name of blues great W.C. Handy? William Christopher Handy What aspiring fiction writer, journalist, and Hopkinsville native, served as editor of three African American weeklies: the Indianapolis Recorder , the Freeman , and the Indianapolis William Alexander 9 Arts Ledger ? Chambers 10 Arts Nat Love wrote what kind of stories? Westerns Cartoonist Morrie Turner created what world famous syndicated 11 Arts comic strip? Wee Pals Who was born in Florence, Alabama in 1873 and is called 12 Arts “Father of the Blues”? WC Handy Georgia Douglas Johnson was a poet during the Harlem Renaissance era.