Diversity in Local Language Maintenance and Restoration: a Reason for Optimism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiocarbon and Linguistic Dates for Occupation of the South Wellesley Islands, Northern Australia

Archaeol. Oceania 45 (2010) 39 –43 Research Report Limited archaeological studies have been conducted in the southern Gulf of Carpentaria. on the adjacent mainland Robins et al. (1998) have reported radiocarbon dates for three sites dating between c.1200 and 200 years ago. For Radiocarbon and linguistic dates for Mornington Island in the north, Memmott et al. (2006:38, occupation of the South Wellesley 39) report dates of c.5000–5500 BP from Wurdukanhan on Islands, Northern Australia the Sandalwood River on the central north coast of Mornington Island. In the Sir Edward Pellew Group 250 km to the northwest of the Wellesleys, Sim and Wallis (2008) SEAN ULM, NICHoLAS EvANS, have documented occupation on vanderlin Island extending DANIEL RoSENDAHL, PAUL MEMMoTT from c.8000 years ago to the present with a major hiatus in and FIoNA PETCHEy occupation between 6700 and 4200 BP linked to the abandonment of the island after its creation and subsequent reoccupation. Keywords: radiocarbon dates, island colonisation, Tindale (1963) recognised the archaeological potential of Kaiadilt people, Kayardild language, Bentinck Island, the Wellesley Islands, undertaking the first excavation in the Sweers Island region at Nyinyilki on the southeast corner of Bentinck Island. A 3' x 7' (91 cm x 213 cm) pit was excavated into the crest of the high sandy ridge separating the beach from Nyinyilki Lake: Abstract The first 20 cm had shells, a ‘nara shell knife, turtle bone. At 20 cm there was a piece of red ochre of a type exactly Radiocarbon dates from three Kaiadilt Aboriginal sites on the parallel with the one which one of the women was using South Wellesley Islands, southern Gulf of Carpentaria, in the camp to dust her thigh in the preparation of rope for demonstrate occupation dating to c.1600 years ago. -

Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes

Abstract Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes Parker Lorber Brody 2020 The Pama-Nyungan language family comprises some 300 Indigenous languages, span- ning the majority of the Australian continent. The varied verb conjugation class systems of the modern Pama-Nyungan languages have been the object of contin- ued interest among researchers seeking to understand how these systems may have changed over time and to reconstruct the verb conjugation class system of the com- mon ancestor of Pama-Nyungan. This dissertation offers a new approach to this task, namely the application of Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction models, which are employed in both testing existing hypotheses and proposing new trajectories for the change over time of the organization of the verbal lexicon into inflection classes. Data from 111 Pama-Nyungan languages was collected based on features of the verb conjugation class systems, including the number of distinct inflectional patterns and how conjugation class membership is determined. Results favor reconstructing a re- stricted set of conjugation classes in the prehistory of Pama-Nyungan. Moreover, I show evidence that the evolution of different parts of the conjugation class sytem are highly correlated. The dissertation concludes with an excursus into the utility of closed-class morphological data in resolving areas of uncertainty in the continuing stochastic reconstruction of the internal structure of Pama-Nyungan. Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Yale University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Parker Lorber Brody Dissertation Director: Dr. Claire Bowern December 2020 Copyright c 2020 by Parker Lorber Brody All rights reserved. -

National Native Title Tribunal

NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 CONTENTS Letter to Attorney-General 1 Table of contents 3 Introduction – President’s Report 5 Tribunal values, mission, vision 9 Corporate overview – Registrar’s Report 10 Corporate goals Goal One: Increase community and stakeholder knowledge of the Tribunal and its processes. 19 Goal Two: Promote effective participation by parties involved in native title applications. 25 Goal Three: Promote practical and innovative resolution of native title applications. 30 Goal Four: Achieve recognition as an organisation that is committed to addressing the cultural and customary concerns of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 44 Goal Five: Manage the Tribunal’s human, financial, physical and information resources efficiently and effectively. 47 Goal Six: Manage the process for authorising future acts effectively. 53 Regional Overviews 59 Appendices Appendix I: Corporate Directory 82 Appendix II: Other Relevant Legislation 84 Appendix III: Publications and Papers 85 Appendix IV: Staffing 89 Appendix V: Consultants 91 Appendix VI: Freedom of Information 92 Appendix VII: Internal and External Scrutiny, Social Justice and Equity 94 Appendix VIII: Audit Report & Notes to the Financial Statements 97 Appendix IX: Glossary 119 Appendix X: Compliance index 123 Index 124 National Native Title Tribunal 3 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1324-9991 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes if an acknowledgment of the source is included. Such use must not be for the purposes of sale or commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without written permission. -

Thuwathu/Bujimulla Indigenous Protected Area

Thuwathu/Bujimulla Indigenous Protected Area MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared by the Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation on behalf of the Traditional Owners of the Wellesley Islands LARDIL KAIADILT YANGKAAL GANGALIDDA This document was funded through the Commonwealth Government’s Indigenous Protected Area program. For further information please contact: Kelly Gardner Land & Sea Regional Coordinator Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation Telephone: (07) 4745 5132 Email: [email protected] Thuwathu/Bujimulla Indigenous Protected Area Management Plan Prepared by Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation on behalf of the Traditional Owners of the Wellesley Islands Acknowledgements: This document was funded through the Commonwealth Government’s Indigenous Protected Area program. The Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation would like to acknowledge and thank the following organisations for their ongoing support for our land and sea management activities in the southern Gulf of Carpentaria: • Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Community (SEWPaC) • Queensland Government Department of Environment and Heritage Protection (EHP) • Northern Gulf Resource Management Group (NGRMG) • Southern Gulf Catchments (SGC) • MMG Century Environment Committee” Photo over page: Whitecliffs, Mornington Island. Photo courtesy of Kelly Gardner. WARNING: This document may contain the names and photographs of deceased Indigenous People. ii Acronyms: AFMA Australian Fisheries Management -

Syntactic Reconstruction by Phonology

The final version of the paper was published in R. Hendery & J. Hendriks eds, Grammatical change: theory and description. Canberra: CLRC/Pacific Linguistics. Syntactic reconstruction by phonology: Edge aligned reconstruction and its application to Tangkic truncation* Erich R. Round, Yale University 1. Introduction This chapter introduces a method for deriving historical syntactic hypotheses from certain types of phonological reconstructions. The method, EDGE ALIGNED RECONSTRUCTION, capitalises on the robust typological generalisation that the edges of high level phonological domains, such as the utterance and intonation phrase, align almost always with the edges of major syntactic domains such as the sentence and the clause (Selkirk 1984, Nespor and Vogel 1986). Essentially, because the highest levels of phonological and syntactic domains are aligned with one another, if a phonological change is reconstructed as having occurred solely at the left edge, right edge, or in the interior of a high level phonological domain, then we predict that the change will have impacted differently on words in initial, final or in medial position within the corresponding syntactic domain. That is, if words can be identified which must have * For helpful comments and discussion I would like to thank Nick Evans, Harold Koch, Mary Laughren, Pat McConvell, David Nash and Jane Simpson as well as two anonymous referees, and Stanley Insler at Yale University. Of course the views expressed here will not always accord with theirs, and all responsibility is my own. Much of this research was spurred by my fieldwork on Kayardild, encouraged by Nick Evans and Janet Fletcher and generously supported by the Hans Rausing Endangered Language Documentation Programme through grants FTG0025 and IGS0039, and particularly, by the Kaiadilt community itself. -

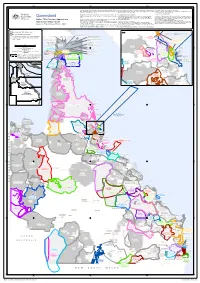

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

A Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands

OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands Dedicated to speakers of the languages of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands and al/ who work to preserve these languages Carrington, L. and Triffitt, G. OZBIB: A linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. D-92, x + 292 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D92.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian NatIonal University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. -

Vernon Ah Kee | Kuku Yalanji/Waanyi/Yidinyji/Guugu Yimithirr People Annie Ah Sam 2008

WILMA WALKER | KUKU YALANJI PEOPLE KAKAN (BASKETS) 2002 ABOUT THE ARTWORK Wilma Walker’s baskets use traditional forms and styles of weaving to reflect on events from the artist’s own history. Walker taught herself to make these baskets by recalling childhood memories of watching women weaving them. As a child, Walker was hidden inside baskets by family members to prevent government officials removing her from her family, as was the government policy at the time. Walker has told of her story: I born up the (Mossman) Gorge on the riverbank in a gunya and police come along look for all the half-caste kids, but they hid me . my mother, we had to hide. In them baskets . and they hide me in that and give me (seed-pod rattles); lot, put in there, keep me quiet . when them police come say ‘No one here. No more kids. All gone . take ’em all away’. ABOUT THE ARTIST Wilma Walker (1929–2008) was an elder of the Kuku Yalanji people from Mossman Gorge, east Cape York. Her Aboriginal names are Ngadijina and Bambimilbirrja. She was one of the few women from her community who continued to weave baskets in the traditional way. Walker promoted her Indigenous culture, particularly by teaching weaving to the children in her community. CONCEPTS Wilma Walker’s art addresses family, race and history, with particular reference to the Stolen Generations. Walker used traditional basket-making to explore historical events, drawing attention to the impact of European settlement on Aboriginal Australians. PRIMARY Question: Why was it important to Wilma Walker to share her childhood memories by weaving baskets? GLOSSARY Activity: Think of a memory you have about your family that is Stolen Generations: ‘The Stolen Generations’ refers to children important to you. -

Ngûrrahmalkwonawoniyan1

ING ISraThEmNalkwona HwoEnRiyE r 1 nLgû an » NICHOLAS EVANS In the Dalabon language of Arnhem Land, which evinced great interest in language in the noun root malk can mean ‘place, country’, all its forms, leading to such ‘monuments to but also ‘season, weather’ as well as ‘place in the human intellect’ as the initiation language a system’, e.g. one’s ‘skin’ in the overarching Damin on Mornington Island that I will say system of kin relations, or the point on a net more about below. But, in contrast to our where the support sticks are fixed. The verb neighbour Aotearoa, these languages are all but root wonan basically means ‘hear, listen’ but is invisible, and inaudible, in the public sphere. regularly extended to other types of non-visual We are at last witnessing long-overdue moves perception, such as smelling, and to thought and to introduce the study of indigenous languages consideration more generally. Combined with into schools, though the states doing this — malk, it means ‘think about where to go, consider New South Wales leading the charge — are, what to do next’. The generous polysynthetic paradoxically, among those in which the effects nature of Dalabon — where polysynthetic denotes of centuries of linguistic dispossession have a type of language which can combine many taken the heaviest toll. elements together into a single verbal word to A common objection to the introduction express what would take a sentence in English — of indigenous languages in schools is their gives us the word ngûrrahmalkwonawoniyan. purported lack of utility — wouldn’t it be more I have chosen it to introduce this essay because useful to study Chinese, Japanese, Spanish etc.? of its ambiguity between ‘let’s listen, let’s attend These objections are simplistic. -

Living on Saltwater Country Saltwater on Living Background

Living on Saltwater Country Background P APER interests in northernReview Australianof literature marine about environments Aboriginal rights, use, management and Living on Saltwater Country Review of literature about Aboriginal rights, use, ∨ management and interests in northern Australian marine environments Healthy oceans: cared for, understood and used wisely for the Healthy wisely benefit of all, now and in the future. Healthy oceans: cared for, for the Healthy understood and used wisely for the benefit of all, oceans: for the National Oceans Office National Oceans Office National Oceans Office Level 1, 80 Elizabeth St, Hobart GPO Box 2139, Hobart, TAS, Australia 7001 Tel: +61 3 6221 5000 Fax: +61 3 6221 5050 www.oceans.gov.au The National Oceans Office is an Executive Agency of the Australian Government Living on Saltwater Country Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be warned that this document may contain images of and quotes from deceased persons. Title: Living on Saltwater Country. Review of literature about Aboriginal rights, use, management and interests in northern Australian marine environments. Copyright: © National Oceans Office 2004 Disclaimers: General This paper is not intended to be used or relied upon for any purpose other than to inform the management of marine resources. The Traditional Owners and native title holders of the regions discussed in this report have not had the opportunity for comment on this document and it is not intended to have any bearing on their individual or group rights, but rather to provide an overview of the use and management of marine resources in the Northern Planning Area for the Northern regional marine planning process. -

Unfinished Business Truth-Telling About

Unfinished business Truth-telling about Aboriginal land rights and native title in the ACT Discussion paper Ed Wensing March 2021 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.16608.61440 Acknowledgement of Country I acknowledge the Traditional Owners on whose Country I live, work and play. I acknowledge that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia are the oldest living culture on Earth, have the oldest continuing land tenure and land use planning and management systems in the World. Your law, knowledge, culture and tradition is a gift to all Australians. I acknowledge that you have suffered the indignity of having your land taken from you without your free, prior and informed consent, without a treaty and without compensation on just terms. I also acknowledge these matters are yet to be justly resolved. Dr Ed Wensing (Life Fellow) FPIA FHEA ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. -

2009 Native Title Report

2009 Native Title Report Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Report No. 2/2010 Australia Post Approval PP255003/04753 © Australian Human Rights Commission 2009 This work is protected by copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part may be used or reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Australian Human Rights Commission. Enquiries should be addressed to Public Affairs at [email protected]. Native Title Report ISSN 1325-6017 (Print) and ISSN 1837-6495 (Online) Acknowledgements The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner acknowledges the work of Australian Human Rights Commission staff, consultants and Aurora Project interns in producing this report (staff: Cecelia Burgman, Nicholas Burrage, Jackie Hartley, Katie Kiss, Priya Panchalingam; interns: Na’ama Carlin, James Malar, Tammy Wong; consultants: Sean Brennan, Leon Terrill). Thank you to Peter Bowen, Manager Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal for assistance in preparing Map 1.1 and Map 3.1. Thank you also to the Western Desert Lands Aboriginal Corporation (Jamukurnu – Yapalikunu), Gabrielle O’Loughlin, and all those who assisted with the production of this Report. This publication can be found in electronic format on the Australian Human Rights Commission’s website at http://www.humanrights.gov.au/social_justice/nt_report/ ntreport09/. For further information about the Australian Human Rights Commission, please visit www.humanrights.gov.au or email [email protected]. You can also write to: Social Justice Unit Australian Human Rights Commission GPO Box 5218 Sydney NSW 2001 Design and layout Jo Clark Printing Paragon Australasia Group Cover photography Fabienne Balsamo, 2009 The cover photograph depicts the Meekin Valley on Maniligarr country, which is situated within Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory.