Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Europe: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 APPENDIX a Waters Assessed for Compliance with Designated Uses

APPENDIX A WATERS ASSESSED FOR COMPLIANCE WITH DESIGNATED USES A - 1 APPENDIX A Waters Assessed For Compliance With Designated Uses The attached tables present lists of rivers, streams, lakes, and estuaries for which water quality data have been assessed and used to determine compliance with designated water uses. EPD considers all water quality related data that is received in its assessment of State waters. The data reviewed for the 2006 305(b) report included EPD monitoring data for rivers and streams, both trend data and intensive survey data, major lakes project data, toxic substances stream monitoring project data, aquatic biomonitoring project data, and coastal monitoring project data. The assessment also included data from other State, Federal, local governments, contracted Clean Lakes projects, electrical utility companies and other groups. A full list of data sources can be found on page A- 13. The lists are divided into three categories; waters supporting designated uses, waters partially supporting designated uses, and waters not supporting designated uses. The lists are organized by water type (rivers/streams, lakes and estuaries). The rivers/streams section is further organized by river basin. The list includes information on the location, data source, designated water use classification, and estimates of stream miles, lake acres or estuary square miles assessed. In addition, for the partial and not supporting lists, information is provided on the criterion violated, potential cause, actions planned to alleviate the problem, estimates of stream miles, lake acres or estuary square miles affected, 303(d) status, and priority. A discussion of the potential cause and actions to alleviate columns along with a discussion of priorities is given below. -

Geological Report on the Foriet Diamond Property, Kuusamo, Finland

National Instrument 43-101 Technical Report GEOLOGICAL REPORT ON THE FORIET DIAMOND PROPERTY, KUUSAMO, FINLAND Latitude/Longitude: N66° 06’ 46.8” E29° 21’ 03.6” ETRS89 UTM: 35W 606212E 7334500N Kuusamo.vaakuna Prepared For: ARCTIC STAR EXPLORATION CORP. BY: KEVIN R. KIVI, P.GEO. KIVI Geoscience Inc. 1100 Memorial Ave, PMB 363, Thunder Bay, ON, P7B 4A3, Canada Phone (807) 285-1251 Fax (807) 285-1252 [email protected] Effective Date: June 18, 2017 GEOLOGICAL REPORT ON THE FORIET DIAMOND PROPERTY, KUUSAMO, FINLAND Cover Image: "Kuusamo.vaakuna" by Care; Original design by Kaj and Terttu Kajander. - Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons CONTENTS 1. Summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. Reliance on Other Experts ...................................................................................................................... 3 4. Property Description and Location .................................................................................................... 5 5. Accessibility, Climate, Local Resources, Infrastructure and Physiography .................... 11 6. History ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Maine Rivers Study

MAINE RIVERS STUDY Final Report State of Maine Department of Conservation U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Mid-Atlantic Regional Office May 1982 Electronic Edition August 2011 DEPLW-1214 i Table of Contents Study Participants i Acknowledgments iii Section I - Major Findings 1 Section II - Introduction 7 Section III - Study Method and Process 8 Step 1 Identification and Definition of Unique River Values 8 Step 2 Identification of Significant River Resource Values 8 Step 3 River Category Evaluation 9 Step 4 River Category Synthesis 9 Step 5 Comparative River Evaluation 9 Section IV - River Resource Categories 11 Unique Natural Rivers - Overview 11 A. Geologic / Hydrologic Features 11 B. River Related Critical / Ecologic Resources 14 C. Undeveloped River Areas 20 D. Scenic River Resources 22 E. Historical River Resources 26 Unique Recreational Rivers - Overview 27 A. Anadromous Fisheries 28 B. River Related Inland Fisheries 30 C. River Related Recreational Boating 32 Section V - Final List of Rivers 35 Section VI - Documentation of Significant River Related 46 (Maps to be linked to GIS) Natural and Recreational Values Key to Documentation Maps 46 Section VII – Options for Conservation of Rivers 127 River Conservation – Energy Development Coordination 127 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Consistency 127 State Agency Consistency 128 Federal Coordination Using the National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act 129 Federal Consistency on Coastal Rivers 129 Designation into National River System 130 ii State River Conservation Legislation -

LUETTELO Kuntien Ja Seurakuntien Tuloveroprosenteista Vuonna 2021

Dnro VH/8082/00.01.00/2020 LUETTELO kuntien ja seurakuntien tuloveroprosenteista vuonna 2021 Verohallinto on verotusmenettelystä annetun lain (1558/1995) 91 a §:n 3 momentin nojalla, sellaisena kuin se on laissa 520/2010, antanut seuraavan luettelon varainhoitovuodeksi 2021 vahvistetuista kuntien, evankelis-luterilaisen kirkon ja ortodoksisen kirkkokunnan seurakuntien tuloveroprosenteista. Kunta Kunnan Ev.lut. Ortodoks. tuloveroprosentti seurakunnan seurakunnan tuloveroprosentti tuloveroprosentti Akaa 22,25 1,70 2,00 Alajärvi 21,75 1,75 2,00 Alavieska 22,00 1,80 2,10 Alavus 21,25 1,75 2,00 Asikkala 20,75 1,75 1,80 Askola 21,50 1,75 1,80 Aura 21,50 1,35 1,75 Brändö 17,75 2,00 1,75 Eckerö 19,00 2,00 1,75 Enonkoski 21,00 1,60 1,95 Enontekiö 21,25 1,75 2,20 Espoo 18,00 1,00 1,80 Eura 21,00 1,50 1,75 Eurajoki 18,00 1,60 2,00 Evijärvi 22,50 1,75 2,00 Finström 19,50 1,95 1,75 Forssa 20,50 1,40 1,80 Föglö 17,50 2,00 1,75 Geta 18,50 1,95 1,75 Haapajärvi 22,50 1,75 2,00 Haapavesi 22,00 1,80 2,00 Hailuoto 20,50 1,80 2,10 Halsua 23,50 1,70 2,00 Hamina 21,00 1,60 1,85 Hammarland 18,00 1,80 1,75 Hankasalmi 22,00 1,95 2,00 Hanko 21,75 1,60 1,80 Harjavalta 21,50 1,75 1,75 Hartola 21,50 1,75 1,95 Hattula 20,75 1,50 1,80 Hausjärvi 21,50 1,75 1,80 Heinola 20,50 1,50 1,80 Heinävesi 21,00 1,80 1,95 Helsinki 18,00 1,00 1,80 Hirvensalmi 20,00 1,75 1,95 Hollola 21,00 1,75 1,80 Huittinen 21,00 1,60 1,75 Humppila 22,00 1,90 1,80 Hyrynsalmi 21,75 1,75 1,95 Hyvinkää 20,25 1,25 1,80 Hämeenkyrö 22,00 1,70 2,00 Hämeenlinna 21,00 1,30 1,80 Ii 21,50 1,50 2,10 Iisalmi -

Answers to the Comments by Reviewer RC2

Answers to the comments by reviewer RC2: General comments: 1) My main issue with this manuscript has to do with its readability. There are numerous grammatical errors throughout, some of which are pointed out below. A native English speaker should edit the paper before resubmission. This is now done. The authors are grateful for the thorough review also concerning the language. 2) The authors tend to make some broad sweeping conclusions based on trends that are only significant across a small fraction of the total study region. I would like to see more discussion of the full picture (like Figure 9). Pg 10 L2 and Pg11 L5 are two instances where the discussion is too narrow in focus. The authors have now extended the mentioned discussions (sections 3.1.1, 3.1.3 and 3.3.) as requested. The systematic signal of change is not as dramatic in Finland as in some areas, because of the large variation of winter weather. Especially the sea ice extent of Baltic Sea affects largely the Finnish winter weather. If the Gulf of Finland and Gulf of Bothnia freeze completely the Finnish climate is almost continental in winter even on the coast. We added a comment about the hemispherical study published recently, where we studied the effect of weather parameters on the observed changes in larger areas. Section 3.1.1 main addition: Especially variable melt onset timing is in the coastal regions (Southwestern Finland and Southern Ostrobothnia) and in the Lake district. For those regions the standard deviation values of the melt onset day are 14.3, 14.7 and 14.6, respectively. -

LIT2013000004 - Andy Gibb.Pdf

•, \.. .. ,-,, i ~ .«t ~' ,,; ~-· ·I NOT\CE OF ENTR'Y.OF APPEARANCE AS AllORNE'< OR REPRESEN1' Al\VE DATE In re: Andrew Roy Gibb October 27, 1978 application for status as permanent resident FILE No. Al I (b)(6) I hereby enter my appearanc:e as attorney for (or representative of), and at the reQUest of, the fol'lowing" named person(s): - NAME \ 0 Petitioner Applicant Andrew Roy Gibb 0 Beneficiary D "ADDRESS (Apt. No,) (Number & Street) (City) (State) (ZIP Code) Mi NAME O Applicant (b)(6) D ADDRESS (Apt, No,) (Number & Street) (City} (ZIP Code) Check Applicable ltem(a) below: lXJ I I am an attorney and a member in good standing of the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States or of the highest court of the following State, territory; insular possession, or District of Columbia A;r;:ka.nsa§ Simt:eme Coy;ct and am not under -a (NBme of Court) court or administrative agency order ·suspending, enjoining, restraining, disbarring, or otherwise restricting me in practicing law. [] 2. I am an accredited representative of the following named religious, charitable, ,social service, or similar organization established in the United States and which is so recognized by the Board: [] i I am associated with ) the. attomey of record who previously fited a notice of appearance in this case and my appearance is at his request. (If '!J<?V. check this item, also check item 1 or 2 whichever is a1wropriate .) [] 4. Others (Explain fully.) '• SIGNATURE COMPLETE ADDRESS Willi~P .A. 2311 Biscayne, Suite 320 ' By: V ? Litle Rock, Arkansas 72207 /I ' f. -

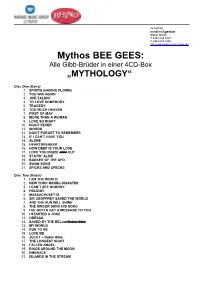

Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in Einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“ Disc One (Barry) 1. SPIRITS (HAVING FLOWN) 2. YOU WIN AGAIN 3. JIVE TALKIN’ 4. TO LOVE SOMEBODY 5. TRAGEDY 6. TOO MUCH HEAVEN 7. FIRST OF MAY 8. MORE THAN A WOMAN 9. LOVE SO RIGHT 10. NIGHT FEVER 11. WORDS 12. DON’T FORGET TO REMEMBER 13. IF I CAN’T HAVE YOU 14. ALONE 15. HEARTBREAKER 16. HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE 17. LOVE YOU INSIDE AND OUT 18. STAYIN’ ALIVE 19. BARKER OF THE UFO 20. SWAN SONG 21. SPICKS AND SPECKS Disc Two (Robin) 1. I AM THE WORLD 2. NEW YORK MINING DISASTER 3. I CAN’T SEE NOBODY 4. HOLIDAY 5. MASSACHUSETTS 6. SIR GEOFFREY SAVED THE WORLD 7. AND THE SUN WILL SHINE 8. THE SINGER SANG HIS SONG 9. I’VE GOTTA GET A MESSAGE TO YOU 10. I STARTED A JOKE 11. ODESSA 12. SAVED BY THE BELL – Robin Gibb 13. MY WORLD 14. RUN TO ME 15. LOVE ME 16. JULIET – Robin Gibb 17. THE LONGEST NIGHT 18. FALLEN ANGEL 19. RINGS AROUND THE MOON 20. EMBRACE 21. ISLANDS IN THE STREAM Disc Three (Maurice) 1. MAN IN THE MIDDLE 2. CLOSER THAN CLOSE 3. DIMENSIONS 4. HOUSE OF SHAME 5. SUDDENLY 6. RAILROAD 7. OVERNIGHT 8. IT’S JUST THE WAY 9. LAY IT ON ME 10. TRAFALGAR 11. OMEGA MAN 12. WALKING ON AIR 13. COUNTRY WOMAN 14. -

Geological Report on the Foriet Diamond Property, Kuusamo, Finland

National Instrument 43-101 Technical Report GEOLOGICAL REPORT ON THE FORIET DIAMOND PROPERTY, KUUSAMO, FINLAND Latitude/Longitude: N66° 06’ 46.8” E29° 21’ 03.6” ETRS89 UTM: 35W 606212E 7334500N Kuusamo.vaakuna Prepared For: ARCTIC STAR EXPLORATION CORP. BY: KEVIN R. KIVI, P.GEO. KIVI Geoscience Inc. 1100 Memorial Ave, PMB 363, Thunder Bay, ON, P7B 4A3, Canada Phone (807) 285-1251 Fax (807) 285-1252 [email protected] Effective Date: June 20, 2017 GEOLOGICAL REPORT ON THE FORIET DIAMOND PROPERTY, KUUSAMO, FINLAND Cover Image: "Kuusamo.vaakuna" by Care; Original design by Kaj and Terttu Kajander. - Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons CONTENTS 1. Summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. Reliance on Other Experts ...................................................................................................................... 3 4. Property Description and Location .................................................................................................... 5 5. Accessibility, Climate, Local Resources, Infrastructure and Physiography .................... 11 6. History ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Genetic Evaluation of the Self-Sustaining Status of a Population of the Endangered Danube Salmon, Hucho Hucho

Hydrobiologia DOI 10.1007/s10750-016-2726-6 PRIMARY RESEARCH PAPER Genetic evaluation of the self-sustaining status of a population of the endangered Danube salmon, Hucho hucho S. Weiss . T. Schenekar Received: 6 October 2015 / Revised: 1 March 2016 / Accepted: 2 March 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract A new multiplex microsatellite protocol Keywords Huchen Á Microsatellites Á Stocking Á was developed for population screening of the endan- Parentage analysis Á IUCN Á European habitat directive gered Danube salmon (or huchen) Hucho hucho. Allelic variation was screened at five newly cloned and four previously published loci in 246 samples to help evaluate the self-sustaining status of an urban Introduction population of huchen in the framework of a contro- versial environmental assessment in the Mur River, The endangered Danube salmon Hucho hucho (Lin- Austria. The loci revealed 78 alleles (mean = 8.6), naeus, 1758), or huchen as commonly known in and in the Mur River an average expected heterozy- Central Europe, is among the largest salmonid fishes in gosity of 0.668. We inferred that the huchen popula- the world. Endemic to the Danube basin, huchen have tion in and around the city of Graz is self-sustaining lost, according to Holcˇ´ık(1990), two-thirds of its based on the following evidence, which includes both global distribution and up to 90% of its original habitat genetic and non-genetic sources of information: (1) in particular regions, such as Austria (Schmutz et al., there is little to no current stocking; (2) presence of 2002). -

Scoping Rogue River's Outstandingly Remarkable

SCOPING ROGUE RIVER’S OUTSTANDINGLY REMARKABLE VALUES Other Similar Values & Other River Values Mike Walker Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society Rogue Advocates Goal One Coalition Preliminary December 8, 2014 SCOPING ROGUE RIVER’S OUTSTANDINGLY REMARKABLE VALUES1 Other Similar Values & Other River Values Outline EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION PURPOSE I. HISTORICAL CHRONOLOGICAL ORV RECORD A. LEGISLATIVE INTENT 1958 Public Land Order (PLO) 1726 dated Sept 3, 1958. Oregon; 1959 PLO 1855 dated May 14, 1959 1961 Senate Select Committee on National Water Resources 1962 Outdoor Recreation for America by Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission 1963 Wild Rivers Study initiated by U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and U.S. Secretary of the Interior 1963 PLO 3165. July 31, 1963. Oregon; 1964 Draft Study Report of the Rogue River, Oregon, Pacific Southwest Reginal Task Force for Consideration of Wild Rivers Study Team. 1964 Wild Rivers Study 1965 Senate Bill S. 1446 by Interior and Insular Affairs Committee 1967 Senate Bill S. 119 by Interior and Insular Affairs Committee 1968 United States Congress. House. 1968. Report No. 1623. Providing for a National Scenic Rivers System and for Other Purposes. 1968 United States Congress. House. 1968. Report No. 1917. National Wild and Scenic Rivers System: Conference Report B. EARLY IMPLEMENTATION OF WILD & SCENIC RIVERS ACT 1968 The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (Public Law 90-542; 16 U.S.C. 1271 et seq.) 1969 Master Plan For The Rogue River Component Of The National Wild & Scenic Rivers System October 1969. USDI, Office of the Secretary. Washington, D.C. 1972 Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. -

Kingdom of Sweden

Johan Maltesson A Visitor´s Factbook on the KINGDOM OF SWEDEN © Johan Maltesson Johan Maltesson A Visitor’s Factbook to the Kingdom of Sweden Helsingborg, Sweden 2017 Preface This little publication is a condensed facts guide to Sweden, foremost intended for visitors to Sweden, as well as for persons who are merely interested in learning more about this fascinating, multifacetted and sadly all too unknown country. This book’s main focus is thus on things that might interest a visitor. Included are: Basic facts about Sweden Society and politics Culture, sports and religion Languages Science and education Media Transportation Nature and geography, including an extensive taxonomic list of Swedish terrestrial vertebrate animals An overview of Sweden’s history Lists of Swedish monarchs, prime ministers and persons of interest The most common Swedish given names and surnames A small dictionary of common words and phrases, including a small pronounciation guide Brief individual overviews of all of the 21 administrative counties of Sweden … and more... Wishing You a pleasant journey! Some notes... National and county population numbers are as of December 31 2016. Political parties and government are as of April 2017. New elections are to be held in September 2018. City population number are as of December 31 2015, and denotes contiguous urban areas – without regard to administra- tive division. Sports teams listed are those participating in the highest league of their respective sport – for soccer as of the 2017 season and for ice hockey and handball as of the 2016-2017 season. The ”most common names” listed are as of December 31 2016. -

Hydrological Study of the Mura River Annex I

University Chair of Hydrology and Hydraulic Engineering of Ljubljana Faculty Jamova 2, p.o.b. 3422 of Civil and Geodetic 1115 Ljubljana, Slovenia Engineering telephone +386 1 47 68 500 fax +386 1 42 50 681 [email protected] Ljubljana, February 6, 2012 Ref.: KSH/d-128 Hydrological study of the Mura river Annex I University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Civil and Geodetic Engineering, Chair of Hydrology and Hydraulic Engineering, Jamova 2, Ljubljana Head of the Chair of Hydrology and Hydraulic Engineering: Prof. Mitja Brilly, PhD Ljubljana, February 2012 2 TABLE OF CONTENT HYDROLOGICAL STATIONS HISTORY ................................................................... 4 AUSTRIA .................................................................................................................... 4 SLOVENIA ............................................................................................................... 34 HUNGARY ............................................................................................................... 47 CROATIA ................................................................................................................. 54 3 Hydrological stations history AUSTRIA Station Code: 2055 Station name: GESTÜTHOF Status: Automatic River: Mur Municipality: Laβnitz bei Murau Location: on right river bank Distance to state border: 270.81 km Area: 1700 km2 GKX: 588928.312 GKY: 221254.531 LON: 14.210278 LAT: 47.111111 Ground ˝zero˝: 776.3 m Purpose: monitoring + prognosis Set: 1959 Alarm: red – 347 cm (19.10.2009) Start: