The Liturgical Reception of Isaiah 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanhedrin 035.Pub

כ"ח אב תשעז“ Sunday, Aug 20 2017 ן ל“ה סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) Capital cases must be completed during the day (cont.) When a kohen becomes disqualified from service מה עבודה שדוחה את השבת רציחה דוחה אותה שנאמר מעם The Gemara continues its tangential discussion of the מזבחי תחקנו למות . הוקע meaning of the term The reason many courts were used to try idolaters in the wilderness is explained. O ur Gemara teaches that beis din may not execute someone on Shabbos. This is determined from a verse, 2) The restriction against convicting someone of a capital which overrides a conclusion we might have determined by קל crime in one day comparing the relationships of certain laws using a The service in the Beis HaMikdash is a very . וחומר R’ Chanina and Rava suggest different sources for the restriction against convicting someone of a capital crime in important mitzvah, and the labors associated with it may one day. even be performed on Shabbos. Yet, we know that a kohen The exchange between R’ Chanina and Rava concerning who commits murder is excluded from performing this ser- their respective sources is recorded. vice, as the verse teaches (Shemos 21:14), “from My altar 3) Holding a trial for a capital case on erev Shabbos or you shall take him away to die.” We might then say that the Yom Tov observance of Shabbos, which is pushed aside in deference The reason a capital case cannot be held on Erev Shab- to the service of the Beis HaMikdash should also be de- bos or Yom Tov is explained. -

Women As Shelihot Tzibur for Hallel on Rosh Hodesh

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 84 William Friedman is a first-year student at YCT Rabbinical School. WOMEN AS SHELIHOT TZIBBUR FOR HALLEL ON ROSH HODESH* William Friedman I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary sifrei halakhah which address the issue of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh are unanimous—they are entirely exempt (peturot).1 The basis given by most2 of them is that hallel is a positive time-bound com- mandment (mitzvat aseh shehazman gramah), based on Sukkah 3:10 and Tosafot.3 That Mishnah states: “One for whom a slave, a woman, or a child read it (hallel)—he must answer after them what they said, and a curse will come to him.”4 Tosafot comment: “The inference (mashma) here is that a woman is exempt from the hallel of Sukkot, and likewise that of Shavuot, and the reason is that it is a positive time-bound commandment.” Rosh Hodesh, however, is not mentioned in the list of exemptions. * The scope of this article is limited to the technical halakhic issues involved in the spe- cific area of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh as it compares to that of men. Issues such as changing minhag, kol isha, areivut, and the proper role of women in Jewish life are beyond that scope. 1 R. Imanu’el ben Hayim Bashari, Bat Melekh (Bnei Brak, 1999), 28:1 (82); Eliyakim Getsel Ellinson, haIsha vehaMitzvot Sefer Rishon—Bein haIsha leYotzrah (Jerusalem, 1977), 113, 10:2 (116-117); R. David ben Avraham Dov Auerbakh, Halikhot Beitah (Jerusalem, 1982), 8:6-7 (58-59); R. -

RCVP: Really Cool

1 RCVP: Really Cool and Valuable Person Compiled by Taylor-Paige Guba, RCVP of NFTY Ohio Valley 2016-2017 with help from past RCVPs and NFTY resources Contact info and Social Media Phone: 317-902-8934 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @ov_rcvp Instagram: @gubagirl Facebook: Taylor-Paige Guba Don’t forget to follow NFTY-OV on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram! Join the NFTY-OV Facebook group! 2 And now a rap from DJ goobz… So listen up peeps. I got a couple things I need you to hear, You better be listening with two ears, The path you are walking down today, Is a dope path so make some way, First you got the R and that’s pretty sweet, Religion is tight so be ready to yeet, The C comes next just creepin on in, Culture is swag so let’s begin, The VP part brings it all together, Wrap it all up and you got 4 letters, Word to yo mamma To clarify, I am very excited to work with all of you fabulous people. Our network has complex responsibilities and I have put everything I could think of that would help us all have a great year in this network packet. Here you will find: ● Some basic definitions ● Standard service outlines ● Jewish holiday dates ● A few other fun items 3 So What Even is Reform Judaism? Great question! It is a pluralistic, progressive, egalitarian sect of Judaism that allows the individual autonomy to decide their personal practices and observations based on all Jewish teachings (Torah, Talmud, Halacha, Rabbis etc.) as well as morals, ethics, reason and logic. -

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

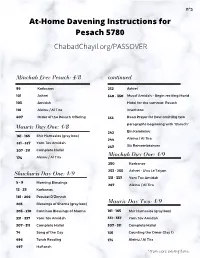

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Torah Weekly

ב ס ״ ד Torah All the Mitzvos in Ki Teitzei concludes with the material world, it is confronted obligation to remember “what by challenges that may require Weekly Parshat Ki Teitzei Amalek did to you on the road, it to engage in battle. Seventy-four of the Torah’s on your way out of Egypt. For there are two aspects to August 15-21 2021 613 commandments (mitzvot) material existence. Our world 7 Elul – 13 Elul, 5781 are in the Parshah of Ki Teitzei. was created because G-d Torah Reading: These include the laws of the “desired a dwelling in the lower Ki Teitzei: Deuteronomy 21:10 - beautiful captive, the War and Peace: Will a worlds,” i.e., the physical 26:19 inheritance rights of the Haftarah: Dove Grow Claws? universe can serve as a dwelling Isaiah 54:1-54:10 firstborn, the wayward and for G-d, a place where His rebellious son, burial and Every day, we conclude essence is revealed. But as the dignity of the dead, returning a the Shemoneh Esreh prayers by term “lower worlds” implies, PARSHAT Ki Teitzei praising G-d “who blesses His lost object, sending away the G-d’s existence is not readily We have Jewish mother bird before taking her people Israel with peace.” And apparent in our environment. when describing the Calendars. If you young, the duty to erect a safety On the contrary, the material would like one, fence around the roof of one’s blessings G-d will bestow upon nature of the world appears to please send us a home, and the various forms of us if we follow His will, our preclude holiness. -

A Guide to Our Shabbat Morning Service

Torah Crown – Kiev – 1809 Courtesy of Temple Beth Sholom Judaica Museum Rabbi Alan B. Lucas Assistant Rabbi Cantor Cecelia Beyer Ofer S. Barnoy Ritual Director Executive Director Rabbi Sidney Solomon Donna Bartolomeo Director of Lifelong Learning Religious School Director Gila Hadani Ward Sharon Solomon Early Childhood Center Camp Director Dir.Helayne Cohen Ginger Bloom a guide to our Endowment Director Museum Curator Bernice Cohen Bat Sheva Slavin shabbat morning service 401 Roslyn Road Roslyn Heights, NY 11577 Phone 516-621-2288 FAX 516- 621- 0417 e-mail – [email protected] www.tbsroslyn.org a member of united synagogue of conservative judaism ברוכים הבאים Welcome welcome to Temple Beth Sholom and our Shabbat And they came, every morning services. The purpose of this pamphlet is to provide those one whose heart was who are not acquainted with our synagogue or with our services with a brief introduction to both. Included in this booklet are a history stirred, and every one of Temple Beth Sholom, a description of the art and symbols in whose spirit was will- our sanctuary, and an explanation of the different sections of our ing; and they brought Saturday morning service. an offering to Adonai. We hope this booklet helps you feel more comfortable during our service, enables you to have a better understanding of the service, and introduces you to the joy of communal worship. While this booklet Exodus 35:21 will attempt to answer some of the most frequently asked questions about the synagogue and service, it cannot possibly anticipate all your questions. Please do not hesitate to approach our clergy or regular worshipers with your questions following our services. -

Pandemic Passover 2.0 Answer to This Question

Food for homeless – page 2 Challah for survivors – page 3 Mikvah Shoshana never closed – page 8 Moving Rabbis – page 10 March 17, 2021 / Nisan 4, 5781 Volume 56, Issue 7 See Marking one year Passover of pandemic life Events March 16, 2020, marks the day that our schools and buildings closed last year, and our lives were and drastically changed by the reality of COVID-19 reaching Oregon. As Resources the soundtrack of the musical “Rent” put it: ~ pages Congregation Beth Israel clergy meet via Zoom using “525,600 minutes, how 6-7 CBI Passover Zoom backgrounds, a collection of which do you measure a year?” can be downloaded at bethisrael-pdx.org/passover. Living according to the Jewish calendar provides us with one Pandemic Passover 2.0 answer to this question. BY DEBORAH MOON who live far away. We measure our year by Passover will be the first major Congregation Shaarie Torah Exec- completing the full cycle Jewish holiday that will be celebrated utive Director Jemi Kostiner Mansfield of holidays and Jewish for the second time under pandemic noticed the same advantage: “Families rituals. Time and our restrictions. and friends from out of town can come need for our community Since Pesach is traditionally home- together on a virtual platform, people and these rituals haven’t stopped in this year, even based, it is perhaps the easiest Jewish who normally wouldn’t be around the though so many of our usual ways of marking these holiday to adapt to our new landscape. seder table.” holy moments have been interrupted. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

Robert M. Andrews the CREATION of a PROTESTANT LITURGY

COMPASS THE CREATION OF A PROTESTANT LITURGY The development of the Eucharistic rites of the First and Second Prayer Books of Edward VI ROBERT M. ANDREWS VER THE YEARS some Anglicans Anglicanism. Representing a study of have expressed problems with the Archbishop Thomas Cranmer's (1489-1556) Oassertion that individuals who were liturgical revisions: the Eucharistic Rites of committed to the main tenets of classical 1549 and 1552 (as contained within the First Protestant theology founded and shaped the and Second Prayer Books of Edward VI), this early development of Anglican theology.1 In essay shows that classical Protestant beliefs 1852, for example, the Anglo-Catholic were influential in shaping the English luminary, John Mason Neale (1818-1866), Reformation and the beginnings of Anglican could declare with confidence that 'the Church theology. of England never was, is not now, and I trust Of course, Anglicanism changed and in God never will be, Protestant'.2 Similarly, developed immensely during the centuries in 1923 Kenneth D. Mackenzie could, in his following its sixteenth-century origins, and 1923 manual of Anglo-Catholic thought, The it is problematic to characterize it as anything Way of the Church, write that '[t]he all- other than theologically pluralistic;7 nonethe- important point which distinguishes the Ref- less, as a theological tradition its genesis lies ormation in this country from that adopted in in a fundamentally Protestant milieu—a sharp other lands was that in England a serious at- reaction against the world of late medieval tempt was made to purge Catholicism English Catholic piety and belief that it without destroying it'.3 emerged from. -

Song of Ascents

Rabbi Jay & Ilana Rabbi Dr. Benny Lau Rabbi Adam Mintz Kelman The Narrative of Sefer Tehillim According to the Contextual Interpretation Online syllabus of 30 lectures Lecture #25 113-118 • Song of Ascents (Mizmorim 120-134) – Structure, 119 Messages & Story • Their location between 119 and before 135-136 120-134 • Comparison Song of Ascent Priestly Blessing • Intertextuality with Ezra & Nechemia 135-136 www.tehillim.org.il The Book of Psalms Beni Gesundheit Interpretation & [email protected] Teachings Ariye Bar Tov, Susan Suna, Audrey Samuels הלל של הלל הלל פסוקי קיבוץ גלויות Hallel of the המצרי הגדול דזמרא Pesukei Great Egyptian Ingathered Dezimra Hallel Hallel Exiles L26 L25 L24 L23 L22 L21 תורה וציון )מזמור א'-ב'( 104-107 108-110 111-118 119-134 135-136 137-145 145-150 Contents Praise and Return to Jerusalem: Praise and Building in Jerusalem: Praise and The Blessing from Praise Thanksgiving Ingathering of the Thanksgiving Praise of the Torah, Thanksgiving Jerusalem: Punishment of Exiles and Going up to the Babylonia and a Call to the Restoration of the Temple and to the City Diaspora for Tikun Olam Davidic Kingdom of David Led by David Said by: Rescued from Returnees to Builders of Israel and the Exile Zion the Land the World תורת ה' )קי"ט( "הלל הגדול" )קל"ה-קל"ו( מהגלות לירושלים ק"כ קכ"א קכ"ב )ד-ה( םשֶׁשָּׁ עָּׁלּו קכ"ג קכ"ד )א( ִשיַּר הַּמֲעלֹות ְׁשָּׁבִטים ִשְׁב טֵ י יָּׁ ּה עֵדּות )א( ִשירַּ הַּמֲעְׁלֹות לָּׁדִו ד ֶׁאל ה' ַּבָּׁצָּׁרָּׁתהִלי ְׁלִי ְׁ ש ָּׁרֵאל תלְׁהֹדֹו לְׁשֵ ם ה': לּולֵי ה' שֶׁהָּׁ יָּׁה לָּׁנּו -

Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected]

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Women's Studies Faculty Publications Women’s Studies 2010 Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Yiddish Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Milligan, Amy, "Shulchan Arukh" (2010). Women's Studies Faculty Publications. 10. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs/10 Original Publication Citation Milligan, A. (2010). Shulchan Arukh. In D. M. Fahey (Ed.), Milestone documents in world religions: Exploring traditions of faith through primary sources (Vol. 2, pp. 958-971). Dallas: Schlager Group:. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains in the fifteenth century (Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains, illustration by Michelet c.1900 (colour litho), Bombled, Louis (1862-1927) / Private Collection / Archives Charmet / The Bridgeman Art Library International) 958 Milestone Documents of World Religions Shulchan Arukh 1570 ca. “A person should dress differently than he does on weekdays so he will remember that it is the Sabbath.” Overview Arukh continues to serve as a guide in the fast-paced con- temporary world. The Shulchan Arukh, literally translated as “The Set Table,” is a compilation of Jew- Context ish legal codes. -

The Psalms As Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A

4 The Psalms as Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A. Rendsburg From as far back as our sources allow, hymns were part of Near Eastern temple ritual, with their performers an essential component of the temple functionaries. 1 These sources include Sumerian, Akkadian, and Egyptian texts 2 from as early as the third millennium BCE. From the second millennium BCE, we gain further examples of hymns from the Hittite realm, even if most (if not all) of the poems are based on Mesopotamian precursors.3 Ugarit, our main source of information on ancient Canaan, has not yielded songs of this sort in 1. For the performers, see Richard Henshaw, Female and Male: The Cu/tic Personnel: The Bible and Rest ~(the Ancient Near East (Allison Park, PA: Pickwick, 1994) esp. ch. 2, "Singers, Musicians, and Dancers," 84-134. Note, however, that this volume does not treat the Egyptian cultic personnel. 2. As the reader can imagine, the literature is ~xtensive, and hence I offer here but a sampling of bibliographic items. For Sumerian hymns, which include compositions directed both to specific deities and to the temples themselves, see Thorkild Jacobsen, The Harps that Once ... : Sumerian Poetry in Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), esp. 99-142, 375--444. Notwithstanding the much larger corpus of Akkadian literarure, hymn~ are less well represented; see the discussion in Alan Lenzi, ed., Reading Akkadian Prayers and Hymns: An Introduction, Ancient Near East Monographs (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 56-60, with the most important texts included in said volume. For Egyptian hymns, see Jan A%mann, Agyptische Hymnen und Gebete, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999); Andre Barucq and Frarn;:ois Daumas, Hymnes et prieres de /'Egypte ancienne, Litteratures anciennes du Proche-Orient (Paris: Cerf, 1980); and John L.