Scoping Rogue River's Outstandingly Remarkable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIT2013000004 - Andy Gibb.Pdf

•, \.. .. ,-,, i ~ .«t ~' ,,; ~-· ·I NOT\CE OF ENTR'Y.OF APPEARANCE AS AllORNE'< OR REPRESEN1' Al\VE DATE In re: Andrew Roy Gibb October 27, 1978 application for status as permanent resident FILE No. Al I (b)(6) I hereby enter my appearanc:e as attorney for (or representative of), and at the reQUest of, the fol'lowing" named person(s): - NAME \ 0 Petitioner Applicant Andrew Roy Gibb 0 Beneficiary D "ADDRESS (Apt. No,) (Number & Street) (City) (State) (ZIP Code) Mi NAME O Applicant (b)(6) D ADDRESS (Apt, No,) (Number & Street) (City} (ZIP Code) Check Applicable ltem(a) below: lXJ I I am an attorney and a member in good standing of the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States or of the highest court of the following State, territory; insular possession, or District of Columbia A;r;:ka.nsa§ Simt:eme Coy;ct and am not under -a (NBme of Court) court or administrative agency order ·suspending, enjoining, restraining, disbarring, or otherwise restricting me in practicing law. [] 2. I am an accredited representative of the following named religious, charitable, ,social service, or similar organization established in the United States and which is so recognized by the Board: [] i I am associated with ) the. attomey of record who previously fited a notice of appearance in this case and my appearance is at his request. (If '!J<?V. check this item, also check item 1 or 2 whichever is a1wropriate .) [] 4. Others (Explain fully.) '• SIGNATURE COMPLETE ADDRESS Willi~P .A. 2311 Biscayne, Suite 320 ' By: V ? Litle Rock, Arkansas 72207 /I ' f. -

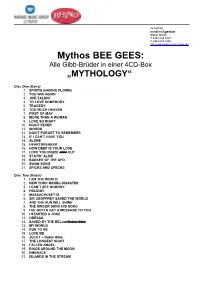

Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in Einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“ Disc One (Barry) 1. SPIRITS (HAVING FLOWN) 2. YOU WIN AGAIN 3. JIVE TALKIN’ 4. TO LOVE SOMEBODY 5. TRAGEDY 6. TOO MUCH HEAVEN 7. FIRST OF MAY 8. MORE THAN A WOMAN 9. LOVE SO RIGHT 10. NIGHT FEVER 11. WORDS 12. DON’T FORGET TO REMEMBER 13. IF I CAN’T HAVE YOU 14. ALONE 15. HEARTBREAKER 16. HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE 17. LOVE YOU INSIDE AND OUT 18. STAYIN’ ALIVE 19. BARKER OF THE UFO 20. SWAN SONG 21. SPICKS AND SPECKS Disc Two (Robin) 1. I AM THE WORLD 2. NEW YORK MINING DISASTER 3. I CAN’T SEE NOBODY 4. HOLIDAY 5. MASSACHUSETTS 6. SIR GEOFFREY SAVED THE WORLD 7. AND THE SUN WILL SHINE 8. THE SINGER SANG HIS SONG 9. I’VE GOTTA GET A MESSAGE TO YOU 10. I STARTED A JOKE 11. ODESSA 12. SAVED BY THE BELL – Robin Gibb 13. MY WORLD 14. RUN TO ME 15. LOVE ME 16. JULIET – Robin Gibb 17. THE LONGEST NIGHT 18. FALLEN ANGEL 19. RINGS AROUND THE MOON 20. EMBRACE 21. ISLANDS IN THE STREAM Disc Three (Maurice) 1. MAN IN THE MIDDLE 2. CLOSER THAN CLOSE 3. DIMENSIONS 4. HOUSE OF SHAME 5. SUDDENLY 6. RAILROAD 7. OVERNIGHT 8. IT’S JUST THE WAY 9. LAY IT ON ME 10. TRAFALGAR 11. OMEGA MAN 12. WALKING ON AIR 13. COUNTRY WOMAN 14. -

Free Flowing Rivers, Sustaining Livelihoods

Free-Flowing Rivers Sustaining Livelihoods, Cultures and Ecosystems About International Rivers International Rivers protects rivers and defends the rights of communities that depend on them. We seek a world where healthy rivers and the rights of local river communities are valued and protected. We envision a world where water and energy needs are met without degrading nature or increasing poverty, and where people have the right to participate in decisions that affect their lives. We are a global organization with regional offices in Asia, Africa and Latin America. We work with river-dependent and dam-affected communities to ensure their voices are heard and their rights are respected. We help to build well-resourced, active networks of civil society groups to demonstrate our collective power and create the change we seek. We undertake independent, investigative research, generating robust data and evidence to inform policies and campaigns. We remain independent and fearless in campaigning to expose and resist destructive projects, while also engaging with all relevant stakeholders to develop a vision that protects rivers and the communities that depend upon them. This report was published as part of the Transboundary Rivers of South Asia (TROSA) program. TROSA is a regional water governance program supported by the Government of Sweden and managed by Oxfam. International Rivers is a regional partner of the TROSA program. Views and opinions expressed in this report are those of International Rivers and do not necessarily reflect those of Oxfam, other TROSA partners or the Government of Sweden. Author: Parineeta Dandekar Editor: Fleachta Phelan Design: Cathy Chen Cover photo: Parineeta Dandekar - Fish of the Free-flowing Dibang River, Arunachal Pradesh. -

Erik Has-Ellison Northwest Classic in Winter Russell

MAGAZINE FEATURED ARTIST RUSSELL WINFIELD + CARING FOR YOUR GUITAR IN WINTER + THE 30TH ANNIVERSARY NORTHWEST CLASSIC + CRAFTSMAN PROFILE ERIK HAS-ELLISON WINTER 2021 | ISSUE #4 CRAFTED IN BEND, OREGON USA THE 2021 WINTER MAGAZINE RUSSELL 17. 4 7. THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST ISSUE WINFIELD41. A COMPANION 3 7. ON THE ROAD CRAFTSMAN THE A Pre-Lockdown Travel Story PROFILE DISCOVERY FROM TOM BEDELL ERIK HAS-ELLISON SERIES In 1990, namesake luthier Larry Breedlove pulled up roots, relocating to the central Oregon high desert. Within a year, he and his mates were crafting the now well-known and well-loved Breedlove Concert THE body—a true landmark in guitar history. That makes 2021, believe it or PREMIER not, the 30th Anniversary of Breedlove building and selling acoustic SERIES guitars! It has been, to say the least, an adventure in innovation. IN GREETINGS In 1995, for example, Breedlove introduced the Northwest Classic, RHYTHM THE SIX using myrtlewood from Oregon’s Pacific coast. Not only did myrtle STRING provide a new look, with wonderfully variegated grain patterns and 25. RESOLUTION 3. wild, almost supernatural colors, it also revealed a new sound, with an unheard-of balance across the entire tonal spectrum. A re-imagined 51. TOMMY 30th Anniversary Northwest Classic is featured in this Breedlove GRAVEN Magazine, alongside many new models that continue the path of innovation. 57. 5. We are also pleased, in this issue, to introduce you to our new MYRTLEWOOD operations manager, Erik Has-Ellison—a singer/songwriter as well as a skilled craftsman who has built Weber mandolins and Bedell and ON THE TRAIL FROM BEND CARING FOR YOUR Breedlove Guitars. -

Exposition of the Sutra of Brahma S

11 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 11 BRAHMA EXPOSITION OF THE SUTRA 梵網經古迹記梵網經古迹記 EXPOSITION OF EXPOSITION OF S NET THETHE SUTRASUTRA OF OF BRAHMABRAHMASS NET NET A. CHARLES MULLER A. COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 11 梵網經古迹記 EXPOSITION OF THE SUTRA OF BRAHMAS NET Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 11 Exposition of the Sutra of Brahma’s Net Edited and Translated by A. Charles Muller Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-14-0 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 11 梵網經古迹記 EXPOSITION OF THE SUTRA OF BRAHMAS NET TRANSLATED BY A. CHARLES MULLER i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. -

Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman AN ELECTRONIC CLASSICS SERIES PUBLICATION Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman is a publication of The Electronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any pur- pose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, The Electronic Clas- sics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU-Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Depart- ment of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Cover Design: Jim Manis; image: Walt Whitman, age 37, frontispiece to Leaves of Grass, Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y., steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost da- guerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Copyright © 2007 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity university. Walt Whitman Contents LEAVES OF GRASS ............................................................... 13 BOOK I. INSCRIPTIONS..................................................... 14 One’s-Self I Sing .......................................................................................... 14 As I Ponder’d in Silence............................................................................... -

Culture in Concrete

CULTURE IN CONCRETE: Art and the Re-imagination of the Los Angeles River as Civic Space by John C. Arroyo B.A., Public Relations Minor, Urban Planning and Development University of Southern California, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2010 © 2010 John C. Arroyo. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. THESIS COMMITTEE A committee of the Department of Urban Studies and Planning has examined this Masters Thesis as follows: Brent D. Ryan, PhD Assistant Professor in Urban Design and Public Policy Thesis Advisor Susan Silberberg-Robinson, MCP Lecturer in Urban Design and Planning Thesis Reader Los Angeles River at the historic Sixth Street Bridge/Sixth Street Viaduct. © Kevin McCollister 2 CULTURE IN CONCRETE: Art and the Re-imagination of the Los Angeles River as Civic Space by John C. Arroyo Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 20, 2010 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning ABSTRACT The Los Angeles River is the common nature of the River space. They have expressed physical, social, and cultural thread that themselves through place-based work, most of connects many of Los Angeles’ most diverse and which has been independent of any formal underrepresented communities, the majority of urban planning, urban design, or public policy which comprise the River’s downstream support or intervention. -

Southern Plains Network Vital Signs Monitoring Plan Appendices

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Southern Plains Network Vital Signs Monitoring Plan Appendices Natural Resource Report NPS/SOPN/NRR-2008/028 ON THE COVER Column 1: Alibates Flint Quarries NM, Sand Creek Massacre NHS, Washita Battlefield NHS, Bent’s Old Fort NHS Column 2: Fort Union NM, Chickasaw NRA, Lake Meredith NRA, Column 3: Capulin Volcano NM, Fort Larned NHS, Lyndon B. Johnson NHP, Pecos NHP Southern Plains Network Vital Signs Monitoring Plan Appendices Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SOPN/NRR-2008/028 U.S.D.I. National Park Service Southern Plains Inventory and Monitoring Network Lora M. Shields Science Bldg., Rm 117 P.O. Box 9000 New Mexico Highlands University Las Vegas, New Mexico 87701 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Inventory & Monitoring Program National Park Service–Intermountain Region 12795 West Alameda Parkway Denver, Colorado 80225 September 2008 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado ii Southern Plains Network Draft Vital Signs Monitoring Plan The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of inter- est and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to en- sure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately writ- ten for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high-priority, cur- rent natural resource management information with managerial application. -

The Hydropolitics of American Literature and Film, 1960-1980

HAUNTED BY WATERS: THE HYDROPOLITICS OF AMERICAN LITERATURE AND FILM, 1960-1980 Zackary Vernon A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Fred Hobson Florence Dore Michael Grimwood Minrose Gwin Randall Kenan © 2014 Zackary Vernon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ZACKARY VERNON: Haunted by Waters: The Hydropolitics of American Literature and Film, 1960-1980 (Under the direction of Fred Hobson) Roman Polanski’s 1974 film Chinatown characterizes the chief engineer of L.A.’s Department of Water and Power as having “water on the brain.” During the 1960s and 1970s numerous Americans shared a similar preoccupation with water as they were inundated with everything from floods to droughts, rivers dammed to rivers on fire, oceanic radiation to lunar seas. Such events quickly became a cultural obsession that coincided with an era of water-related political debates about the preservation of the nation’s aquatic ecosystems. I contend that these hydropolitical concerns had far-ranging implications; in an era when unease over damming and industrial contamination converged with a larger Cold War culture of containment and conformity, many postwar Americans were attracted to and identified with neo-romantic images of “wild,” “natural” water. However, the irreconcilable gap between these images and the unprecedented water crises of the period gave rise to crises of the self. Such existential fears were amplified as nuclear societies confronted the all-too-real prospect of an end of nature and the corresponding end of humanity. -

Introduction Landscape, Character, and Analogical Imagination

1 introduction Landscape, character, and Analogical imagination If historical writing is a continual dialectical warfare between past and present—a continual shaping and forcing of the configuration of the past so as to release from it the meanings it always had, but never dared to state out loud, the meanings that permeated it as an unbreathable atmosphere or shameful secret—then what entities and images will come first? —T. J. Clark, “Reservations of the Marvellous” Over its short life, the nation of South Africa has become known for its turbulent political history as well as the distinctiveness of its landscapes, yet relatively little at- tention has been paid to how these two factors might have been connected. The emer- gence of a white society that called itself “South African” in the twentieth century has usually been ascribed to an intertwining of economics, class, and race, and the role of geographical factors in this process has largely been seen in instrumental terms, focusing on resource competition, the spatialization of ideology through segregation- ist legislation, and shifting attitudes toward nature.1 While much has been written on land use, settlement patterns, property relations, and the influence of the frontier experience on the subsequent human-land relationships in the subcontinent,2 the imaginaries and iconographies that underpinned this territorialization have only recently started to receive attention, more often from archaeologists, cultural histori- _________ 1 ans, literary theorists, and architects than from geographers.3 This is understandable. landscape, Because the politics of imperialism, nationalism, economic maximization, and racial character, and difference have dominated South Africa’s history over the last century, utilitarian analogical rather than aesthetic analyses have often seemed more appropriate to thinking about imagination relations between humans and the environment in the subcontinent. -

Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Europe: an Overview

sustainability Article Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Europe: An Overview Tobias Schäfer † Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB), 12587 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] † Present address: WWF Germany, 10117 Berlin, Germany. Abstract: Most of Europe’s rivers are highly fragmented by barriers. This study examines legal protection schemes, that specifically aim at preserving the free-flowing character of rivers. Based on national legislation, such schemes are found in seven European countries: Slovenia, Finland, Sweden, France and Spain as well as Norway and Iceland. The study provides an overview of the individual schemes and their respective scope, compares their protection mechanisms and assesses their effec- tiveness. As Europe’s the remaining free-flowing rivers are threatened by hydropower and other development, the need for effective legal protection, comparable to the designation of Wild and Scenic Rivers in the United States, is urgent. Similarly, any ambitious strategy for the restoration of free-flowing rivers should be complemented with a mechanism for their permanent protection once dams and other barriers are removed. The investigated legal protection schemes constitute a starting point for envisioning a more cohesive European network of strictly protected free-flowing rivers. Keywords: free-flowing rivers; strict protection; protected areas; legal river protection schemes; river nature reserves; dam removal; river restoration; EU Biodiversity Strategy Citation: Schäfer, T. Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Europe: An Overview. Sustainability 1. Introduction 2021, 13, 6423. https://doi.org/ Europe’s last wild rivers and dynamic river landscapes deserve better protection. 10.3390/su13116423 This study examines existing legal protection mechanisms for free-flowing rivers in Europe in order to draw conclusions for more cohesive European policies for river protection. -

Dam Removal Success Stories

DAM REMOVAL SUCCESS STORIES R ESTORING R IVERS THROUGH S ELECTIVE R EMOVAL OF D AMS THAT D ON’ T M AKE S ENSE DECEMBER 1999 DAM REMOVAL SUCCESS STORIES R ESTORING R IVERS THROUGH S ELECTIVE R EMOVAL OF D AMS THAT D ON’ T M AKE S ENSE DECEMBER 1999 This report was prepared by Friends of the Earth, American Rivers, and Trout Unlimited in December 1999. Cover Photographs: Sandstone Dam on the Kettle River in Minnesota Source: Ian Chisholm, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Cover Design: Gallagher/Wood Design Text Design: American Rivers (c) December 1999 by American Rivers, Friends of the Earth, & Trout Unlimited. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 0-913890-96-0 Printed with soy ink on 100% recycled, 30% post consumer waste, chlorine free paper. Dam Removal Success Stories Final Report iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Edited by Elizabeth Maclin and Matt Sicchio of American Rivers, with contributions from American Rivers staff Margaret Bowman, Steve Brooke, Jocelyn Gibbon and Amy Souers; Friends of the Earth staff Brent Blackwelder, Shawn Cantrell and Lisa Ramirez; and Trout Unlimited staff Brian Graber, Sara Johnson and Karen Tuerk. Thanks also to the following individuals for their assistance in the research and writing phase of this publication: Ian Chisholm, Karen Cozzetto, David Cummings, John Exo, Bob Hunter, Lance Laird, Stephanie Lindloff, David Morrill, Richard Musgrove, Dirk Peterson, Tom Potter, Craig Regalia, Elizabeth Ridlington, Jed Volkman, Bob Wengrzynek and Laura Wildman. Special thanks to the many local contacts (listed in each case study) who gave so generously of their time, and without whom this report would not have been possible.