River Stewardship Toolkit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Ticket Awards • September 16 & 17, 2011 COURTESY S

GOLDEN TICKET BONUS ISSUE TM www.GoldenTicketAwards.com Vol. 15 • Issue 6.2 SEPTEMBER 2011 Holiday World hosts Golden Ticket event for third time Amusement Today sees the biggest voter response in survey history 2011 . P . I GOLDEN TICKET . V AWARDS BEST OF THE BEST! Holiday World & Splashin’ Safari Host Park • 2011 Golden Ticket Awards • September 16 & 17, 2011 COURTESY S. MADONNA HORCHER STORY: Tim Baldwin strate the big influx of additional voters. [email protected] Tabulating hundreds of ballots can seem SANTA CLAUS, Indiana — It was Holiday like a somewhat tedious and daunting task, World’s idea for Amusement Today to pres- but a few categories were such close races, ent the Golden Ticket Awards live in 2000. that a handful of winners were not determined The ceremony was on the simple side, and until the very last ballots in the last hour of now over a decade later, the park welcomes tabulation. These ‘nail biters’ always keep us AT for the third time. A lot has changed since on our toes that there is never a guarantee of that time, as the Golden Ticket Awards cere- any category. mony has grown into a popular industry event, The dedication of our voters is also admi- filled with networking opportunities and occa- rable. People have often gone to great lengths sions to see what is considered the best in the to make sure we receive their ballot in time. industry. And as mentioned before, every vote abso- What has also grown is the voter response. lutely counts as just a few ballots determined The 2011 awards saw the biggest response some winning categories. -

Mississippi Whitewater Park

Mississippi Whitewater Park Management and Operational Responsibilities A report to the Minnesota Legislature Pursuant to the Laws of Minnesota 2005, 1st Special Session Chapter 1-S.F.No.69 Article 2, Sec. 3. Subd. 6 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources February 15, 2006 Mississippi Whitewater Park Management and Operational Responsibilities Pursuant to the Laws of Minnesota 2005, 1st Special Session Chapter 1 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources February 15, 2006 Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources is available to all individuals regardless of race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, status with regard to public assistance, age, sexual orientation, or disability. Discrimination inquiries should be sent to MN DNR, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4031; or the Equal Opportunity Office, Department of the Interior, Washington, DC 20240. This document is available in alternative formats by contacting the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. © 2006 State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources Cover graphic is from the Feasibility Study for Mississippi Whitewater Park, Minneapolis, Minnesota, dated June 30, 1999. Prepared by McLaughlin Water Engineers and a consultant team. Site planning and illustrations by Damon Farber Associates, Inc. Table of Contents Chapter 1: Legislative Authorization, Definitions, and Executive Summary……1 Chapter 2: Overview of Project…………………………………………………………….7 Chapter 3: Management and Operational -

CANOEING INTERNATIONAL Edito-Sommaire 26/12/06 19:14 Page 5

Edito-Sommaire 26/12/06 19:14 Page 4 Table of contents P.3 EDITORIAL P.26-67 EVENTS 2006-2007 World Championships 2006..........................p.27-51 P.6-19 NEWS AND ACTUALITY • Flatwater Racing in Szeged (HUN) P.20-25 PORTFOLIO • Report Chairman Flatwater Racing Committee • Slalom Racing in Prague (CZE) • Slalom Racing Juniors in Solkan (SLO) • Wildwater Racing in Karlovy Vary (CZE) • Marathon Racing in Tremolat (FRA) • Report Chairman Marathon Racing Committee • Canoe Polo in Amsterdam (NED) • Dragonboat Racing in Kaohsiung (TPE) World Championships 2007..........................p.52-65 • Flatwater Racing in Duisburg (GER • Flatwater Racing Junior in Racice (CZE) • Slalom Racing in Foz d’Iguassu (BRA) • Wildwater Racing in Columbia (USA) • Marathon Racing in Györ (HUN) • Dragonboat Racing in Gerardmer (FRA) • Freestyle in Ottawa (CAN) Multidiscipline Events ......................................p.66-67 P.68-73 ADVENTURE Keeping the pace in Dubai p.68-69 Steve Fisher p.70-73 P.75-86 PADDLING AND SOCIETY New actions for Paddleability p.76 River cleaning operation in Kenya p.77 World Canoeing Day p.78 ICF Development Programme p.80-85 Canoeing for health p.86 4 CANOEING INTERNATIONAL Edito-Sommaire 26/12/06 19:14 Page 5 P.88-92 FOCUS A new era of canoeing in the world of television p.89-92 P.93-99 PROFILES Katalin Kovacs / Natsa Janics p.94-95 Michala Mruzkova p.96 Meng Guang Liang p.98-99 P.100-102 HISTORY Gert Fredriksson (1919-2006) p.100-102 P.103-111 INTERNATIONAL PADDLING FEDERATIONS Life Saving p.104-105 Waveski p.106-107 Va’a p.108-109 Rafting p.110-111 P.113-122 VENUES Olympic Water Stadiums p.114-117 Beijing 2008 p.119-120 London 2012 p.121-122 5 EBU 22/12/06 10:44 Page 1 Edito-Sommaire 22/12/06 10:34 Page 3 Foreword Dear friends of canoeing, It is a great pleasure to introduce this second edition of the new-look Canoeing International. -

PHS 542 Theory and Homework in 2018

PHS 542 (Summer, 2018, 5 weeks) Daily Details This file contains daily handouts, including theory & activities, as well as homework assignments. A separate file is basically an instructors’ solution manual, containing answers to selected activities and homework keys, the quizzes used during the course, and quiz keys. Week 1 --- Day 1 1 Syllabus: PHS 542: Integrated Math and Physics Summer at ASU (2018: Bob Rowley, [email protected]) Catalog description: Mathematical models and modeling as an integrating theme for secondary mathematics and physics. Enrollment by teams of mathematics and physics teachers encouraged. COURSE DESCRIPTION: A. Overview: Week 1: Teaching theory with Dr. Hestenes, introduction to the four math models, introductory activities with Geogebra and GlowScript. Week 2: Math Model 1 (MM1: constant rate of change), similarity & ratio problems, linear graphs, slopes. Introduction to Geometric Algebra (GA) in 2D. Introduction to MM2 (constant change in rate), parabolas and their graphs. Week 3: Continue MM2, parabolas in projectile motion, GA Primer treatment. MM3 (rate proportional to amount), exponentials and their graphs, Professor Bartlett’s treatment of exponential growth and non-renewable resource lifetime. Week 4: MM4 (change in rate proportional to amount), trig functions, Euler’s formula as used in GA, oscillatory motion in physics applications. GA Primer topics in classical physics, 3D rotations. Week 5: Continue GA Primer topics. Beginning relativity using GA treatment. Some standard relativity examples from the GA viewpoint. B. Course plan and rationale: Daily handouts. Some theory, many cooperative practice activities, homework assignments, and either a final exam or final project. One goal is to deepen teacher understanding of the importance of the mathematical models which span a large portion of physics topics. -

Cambridge Canoe Club Newsletter

Volume 1, Issue 2 Cambridge Canoe Spring 2010 Club Newsletter http://www.cambridgecanoeclub.org.uk This newsletter relies on contri- butions from members. If you have been on a My Club Experience by David Huddleston trip, have a point of view or news write it down and send it in to News- Hi, my name is David and I am [email protected]. thirteen years old. I joined the Articles should be between 75 and canoe club three years ago. I 150 words long and can be accom- started at the Abbey swimming panied by a picture. pool before moving onto the Cam where I did my 1 star course. Then I had a go with some white water at Cardington Special points of interest: which I really enjoyed. I must say thank you to the club Meet Dave Barton which has helped me and been very friendly. My dad started Trip reports kayaking with me but he does- n’t like white water so I really Water safety: Entrapment appreciate others who have taken the time to help me with First aid course this. The Wednesday evening David at the Nene White Water Centre series is a good way to develop Club Diary skills in a kayak, and I like going Another trip I have been on is the St. Ives area which was nice. to the sluice where I learnt the Hauxton Mill run to the club- about moving water. house – this was interesting My favourite activity though because part of the Cam was I have been lucky and managed must be white water, Cardington being drained which meant that to get my own boat, a Dagger was a great start but the Nene is Inside this issue: it had a fairly fast flow and we Blast - ‘Blasty’, which is a nice a lot better and thanks to Simon were able to go over the weir at general purpose boat, along and Terry for organising the trips Byron’s. -

Podolak Multifunctional Riverscapes

Multifunctional Riverscapes: Stream restoration, Capability Brown’s water features, and artificial whitewater By Kristen Nicole Podolak A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor G. Mathias Kondolf, Chair Professor Louise Mozingo Professor Vincent H. Resh Spring 2012 i Abstract Multifunctional Riverscapes by Kristen Nicole Podolak Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor G. Mathias Kondolf, Chair Society is investing in river restoration and urban river revitalization as a solution for sustainable development. Many of these river projects adopt a multifunctional planning and design approach that strives to meld ecological, aesthetic, and recreational functions. However our understanding of how to accomplish multifunctionality and how the different functions work together is incomplete. Numerous ecologically justified river restoration projects may actually be driven by aesthetic and recreational preferences that are largely unexamined. At the same time river projects originally designed for aesthetics or recreation are now attempting to integrate habitat and environmental considerations to make the rivers more sustainable. Through in-depth study of a variety of constructed river landscapes - including dense historical river bend designs, artificial whitewater, and urban stream restoration this dissertation analyzes how aesthetic, ecological, and recreational functions intersect and potentially conflict. To explore how aesthetic and biophysical processes work together in riverscapes, I explored the relationship between one ideal of beauty, an s-curve illustrated by William Hogarth in the 18th century and two sets of river designs: 18th century river designs in England and late 20th century river restoration designs in North America. -

Tour of the Park - Scandinavia 4/15/18, 3:53 PM Worlds of Fun Tour of the Park 2017 Edition

Tour of the Park - Scandinavia 4/15/18, 3:53 PM Worlds of Fun Tour of the Park 2017 Edition Scandinavia Africa Europa Americana Planet Snoopy The Orient Please be aware that this page is currently under construction and each ride and attraction will be expanded in the future to include its own separate page with additional photos and details. Scandinavia Since the entrance to the park is causing a significant change to the layout and attractions to Scandinavia please be aware this entry will not be entirely accurate until the park opens in spring 2017 Scandinavia Main Gate 2017-current In 2017 the entire Scandinavian gate was rebuilt and redesigned, complete with the iconic Worlds of Fun hot air balloon, and Guest Relations that may be entered by guests from both inside and outside the park. The new gate replaces the original Scandinavian gate built in 1973 and expanded in 1974 to serve as the park's secondary or back gate. With the removal of the main Americana gate in 1999, the Scandinavian gate began serving as the main gate. Grand Pavilion 2017-current http://www.worldsoffun.org/totp/totp_scandinavia.html Page 1 of 9 Tour of the Park - Scandinavia 4/15/18, 3:53 PM Located directly off to the left following the main entrance, the Grand Pavilion added in 2017 serves as the park's largest picnic and group catering facility. Visible from the walkway from the back parking lots the Grand Pavilion is bright and open featuring several large picnic pavilions for catering events as well as its own catering kitchen. -

LIT2013000004 - Andy Gibb.Pdf

•, \.. .. ,-,, i ~ .«t ~' ,,; ~-· ·I NOT\CE OF ENTR'Y.OF APPEARANCE AS AllORNE'< OR REPRESEN1' Al\VE DATE In re: Andrew Roy Gibb October 27, 1978 application for status as permanent resident FILE No. Al I (b)(6) I hereby enter my appearanc:e as attorney for (or representative of), and at the reQUest of, the fol'lowing" named person(s): - NAME \ 0 Petitioner Applicant Andrew Roy Gibb 0 Beneficiary D "ADDRESS (Apt. No,) (Number & Street) (City) (State) (ZIP Code) Mi NAME O Applicant (b)(6) D ADDRESS (Apt, No,) (Number & Street) (City} (ZIP Code) Check Applicable ltem(a) below: lXJ I I am an attorney and a member in good standing of the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States or of the highest court of the following State, territory; insular possession, or District of Columbia A;r;:ka.nsa§ Simt:eme Coy;ct and am not under -a (NBme of Court) court or administrative agency order ·suspending, enjoining, restraining, disbarring, or otherwise restricting me in practicing law. [] 2. I am an accredited representative of the following named religious, charitable, ,social service, or similar organization established in the United States and which is so recognized by the Board: [] i I am associated with ) the. attomey of record who previously fited a notice of appearance in this case and my appearance is at his request. (If '!J<?V. check this item, also check item 1 or 2 whichever is a1wropriate .) [] 4. Others (Explain fully.) '• SIGNATURE COMPLETE ADDRESS Willi~P .A. 2311 Biscayne, Suite 320 ' By: V ? Litle Rock, Arkansas 72207 /I ' f. -

The Non-Stop Course Record of the Devizes to Westminster International Canoe Race

The non-stop course record of the Devizes to Westminster International Canoe Race 2019 marks the 40th anniversary of the DW non-stop course record, set by Brian Greenham and Tim Cornish of Richmond and Reading Canoe Clubs. The record stands at 15 hours 34 minutes and despite better boat technology and improved training, it has (officially, at least) remained untouched. Steve Baker and Duncan Capps of Richmond Canoe Club and the Army Canoe Union surpassed it in 2000 with a time of 15 hours 18 minutes, but by the time they reached Westminster the race had long been cancelled due to the dangerous conditions, and their ‘new’ record was disregarded Breaking the record requires a combination of factors: a genuinely world- class crew, little wind (or a tail wind at worst), and good flow on the Kennet and Thames. This combination has eluded the race for some time. Below is a short Q&A with Brian Greenham and Tim Cornish to mark the 40th anniversary of their record-breaking run follows: Q: What does setting the DW record mean to you now? Tim: When we set the record in 1979 we already had the record from the previous year and it was being broken regularly so it was not that significant at the time. Winning the race was the thing. As time has passed I guess it has become more meaningful and significant. Brian: I think the one big advantage I always feel we had was we were not trying to set a record but just trying to win. -

Mississippi White Water Park Design Report Outline June 30, 1999

Mississippi White Water Park Design Report Outline June 30, 1999 Executive Summary Section 1 – Literature Search .................................................................................... 1-1 Section 2 – Public Input ............................................................................................ 2-1 Section 3 – Impacts Analysis.................................................................................... 3-1 • Social Impacts..................................................................................................... 3-1 • Economic Impacts .............................................................................................. 3-2 • Site Impacts ...................................................................................................... 3-26 Section 4 – Design and Engineering - Site Design.................................................. 4-1 • White Water Courses - 3 Alternatives ............................................................. 4-1 • Architectural Program....................................................................................... 4-3 • Site Master Plan.................................................................................................. 4-9 Section 5 – Design and Engineering – Hydraulics ................................................. 5-1 • Inlet/Outlet works............................................................................................. 5-1 • Flood Plain....................................................................................................... -

Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in Einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“

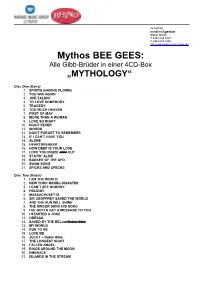

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“ Disc One (Barry) 1. SPIRITS (HAVING FLOWN) 2. YOU WIN AGAIN 3. JIVE TALKIN’ 4. TO LOVE SOMEBODY 5. TRAGEDY 6. TOO MUCH HEAVEN 7. FIRST OF MAY 8. MORE THAN A WOMAN 9. LOVE SO RIGHT 10. NIGHT FEVER 11. WORDS 12. DON’T FORGET TO REMEMBER 13. IF I CAN’T HAVE YOU 14. ALONE 15. HEARTBREAKER 16. HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE 17. LOVE YOU INSIDE AND OUT 18. STAYIN’ ALIVE 19. BARKER OF THE UFO 20. SWAN SONG 21. SPICKS AND SPECKS Disc Two (Robin) 1. I AM THE WORLD 2. NEW YORK MINING DISASTER 3. I CAN’T SEE NOBODY 4. HOLIDAY 5. MASSACHUSETTS 6. SIR GEOFFREY SAVED THE WORLD 7. AND THE SUN WILL SHINE 8. THE SINGER SANG HIS SONG 9. I’VE GOTTA GET A MESSAGE TO YOU 10. I STARTED A JOKE 11. ODESSA 12. SAVED BY THE BELL – Robin Gibb 13. MY WORLD 14. RUN TO ME 15. LOVE ME 16. JULIET – Robin Gibb 17. THE LONGEST NIGHT 18. FALLEN ANGEL 19. RINGS AROUND THE MOON 20. EMBRACE 21. ISLANDS IN THE STREAM Disc Three (Maurice) 1. MAN IN THE MIDDLE 2. CLOSER THAN CLOSE 3. DIMENSIONS 4. HOUSE OF SHAME 5. SUDDENLY 6. RAILROAD 7. OVERNIGHT 8. IT’S JUST THE WAY 9. LAY IT ON ME 10. TRAFALGAR 11. OMEGA MAN 12. WALKING ON AIR 13. COUNTRY WOMAN 14. -

THE RIVER THAMES a Complete Guide to Boating Holidays on the UK’S Most Famous River the River Thames a COMPLETE GUIDE

THE RIVER THAMES A complete guide to boating holidays on the UK’s most famous river The River Thames A COMPLETE GUIDE And there’s even more! Over 70 pages of inspiration There’s so much to see and do on the Thames, we simply can’t fit everything in to one guide. 6 - 7 Benson or Chertsey? WINING AND DINING So, to discover even more and Which base to choose 56 - 59 Eating out to find further details about the 60 Gastropubs sights and attractions already SO MUCH TO SEE AND DISCOVER 61 - 63 Fine dining featured here, visit us at 8 - 11 Oxford leboat.co.uk/thames 12 - 15 Windsor & Eton THE PRACTICALITIES OF BOATING 16 - 19 Houses & gardens 64 - 65 Our boats 20 - 21 Cliveden 66 - 67 Mooring and marinas 22 - 23 Hampton Court 68 - 69 Locks 24 - 27 Small towns and villages 70 - 71 Our illustrated map – plan your trip 28 - 29 The Runnymede memorials 72 Fuel, water and waste 30 - 33 London 73 Rules and boating etiquette 74 River conditions SOMETHING FOR EVERY INTEREST 34 - 35 Did you know? 36 - 41 Family fun 42 - 43 Birdlife 44 - 45 Parks 46 - 47 Shopping Where memories are made… 48 - 49 Horse racing & horse riding With over 40 years of experience, Le Boat prides itself on the range and 50 - 51 Fishing quality of our boats and the service we provide – it’s what sets us apart The Thames at your fingertips 52 - 53 Golf from the rest and ensures you enjoy a comfortable and hassle free Download our app to explore the 54 - 55 Something for him break.