Introduction Landscape, Character, and Analogical Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

History 1886

How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an African? Updated December 2009 A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family - Our Story Part D: 1886 - 1909 Compiled by: Dr. Anthony Turton [email protected] Caution in the use and interpretation of these data This document consists of events data presented in chronological order. It is designed to give the reader an insight into the complex drivers at work over time, by showing how many events were occurring simultaneously. It is also designed to guide future research by serious scholars, who would verify all data independently as a matter of sound scholarship and never accept this as being valid in its own right. Read together, they indicate a trend, whereas read in isolation, they become sterile facts devoid of much meaning. Given that they are “facts”, their origin is generally not cited, as a fact belongs to nobody. On occasion where an interpretation is made, then the commentator’s name is cited as appropriate. Where similar information is shown for different dates, it is because some confusion exists on the exact detail of that event, so the reader must use caution when interpreting it, because a “fact” is something over which no alternate interpretation can be given. These events data are considered by the author to be relevant, based on his professional experience as a trained researcher. Own judgement must be used at all times . All users are urged to verify these data independently. The individual selection of data also represents the author’s bias, so the dataset must not be regarded as being complete. -

TV on the Afrikaans Cinematic Film Industry, C.1976-C.1986

Competing Audio-visual Industries: A business history of the influence of SABC- TV on the Afrikaans cinematic film industry, c.1976-c.1986 by Coenraad Johannes Coetzee Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art and Sciences (History) in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Anton Ehlers December 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za THESIS DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS Historical research frequently requires investigations that have ethical dimensions. Although not to the same extent as in medical experimentation, for example, the social sciences do entail addressing ethical considerations. This research is conducted at the University of Stellenbosch and, as such, must be managed according to the institution’s Framework Policy for the Assurance and Promotion of Ethically Accountable Research at Stellenbosch University. The policy stipulates that all accumulated data must be used for academic purposes exclusively. This study relies on social sources and ensures that the university’s policy on the values and principles of non-maleficence, scientific validity and integrity is followed. All participating oral sources were informed on the objectives of the study, the nature of the interviews (such as the use of a tape recorder) and the relevance of their involvement. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

LIT2013000004 - Andy Gibb.Pdf

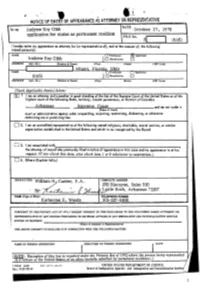

•, \.. .. ,-,, i ~ .«t ~' ,,; ~-· ·I NOT\CE OF ENTR'Y.OF APPEARANCE AS AllORNE'< OR REPRESEN1' Al\VE DATE In re: Andrew Roy Gibb October 27, 1978 application for status as permanent resident FILE No. Al I (b)(6) I hereby enter my appearanc:e as attorney for (or representative of), and at the reQUest of, the fol'lowing" named person(s): - NAME \ 0 Petitioner Applicant Andrew Roy Gibb 0 Beneficiary D "ADDRESS (Apt. No,) (Number & Street) (City) (State) (ZIP Code) Mi NAME O Applicant (b)(6) D ADDRESS (Apt, No,) (Number & Street) (City} (ZIP Code) Check Applicable ltem(a) below: lXJ I I am an attorney and a member in good standing of the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States or of the highest court of the following State, territory; insular possession, or District of Columbia A;r;:ka.nsa§ Simt:eme Coy;ct and am not under -a (NBme of Court) court or administrative agency order ·suspending, enjoining, restraining, disbarring, or otherwise restricting me in practicing law. [] 2. I am an accredited representative of the following named religious, charitable, ,social service, or similar organization established in the United States and which is so recognized by the Board: [] i I am associated with ) the. attomey of record who previously fited a notice of appearance in this case and my appearance is at his request. (If '!J<?V. check this item, also check item 1 or 2 whichever is a1wropriate .) [] 4. Others (Explain fully.) '• SIGNATURE COMPLETE ADDRESS Willi~P .A. 2311 Biscayne, Suite 320 ' By: V ? Litle Rock, Arkansas 72207 /I ' f. -

South Africa Mobilises: the First Five Months of the War Dr Anne Samson

5 Scientia Militaria vol 44, no 1, 2016, pp 5-21. doi:10.5787/44-1-1159 South Africa Mobilises: The First Five Months of the War Dr Anne Samson Abstract When war broke out in August 1914, the Union of South Africa found itself unprepared for what lay ahead. When the Imperial garrison left the Union during September 1914, supplies, equipment and a working knowledge of British military procedures reduced considerably. South Africa was, in effect, left starting from scratch. Yet, within five months and despite having to quell a rebellion, the Union was able to field an expeditionary force to invade German South West Africa and within a year agree to send forces to Europe and East Africa. This article explores how the Union Defence Force came of age in 1914. Keywords: South Africa, mobilisation, rebellion, Union Defence Force, World War 1 1. Introduction In August 1914, South Africa, along with many other countries, found itself at war. It was unprepared for this eventuality – more so than most other countries. Yet, within six weeks of war being declared, the Union sent a force into neighbouring German South West Africa. This was a remarkable achievement considering the Union’s starting point, and that the government had to deal with a rebellion, which began with the invasion. The literature on South Africa’s involvement in World War 1 is increasing. Much of it focused on the war in Europe1 and, more recently, on East Africa2 with South West Africa3 starting to follow. However, the home front has been largely ignored with most literature focusing on the rebellion, which ran from September to December 1914.4 This article aims to explore South Africa’s preparedness for war and to shed some insight into the speed with and extent to which the government had to adapt in order to participate successfully in it. -

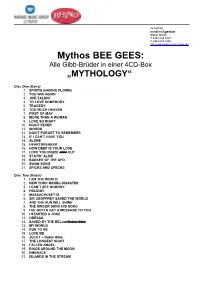

Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in Einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] Mythos BEE GEES: Alle Gibb-Brüder in einer 4CD-Box „MYTHOLOGY“ Disc One (Barry) 1. SPIRITS (HAVING FLOWN) 2. YOU WIN AGAIN 3. JIVE TALKIN’ 4. TO LOVE SOMEBODY 5. TRAGEDY 6. TOO MUCH HEAVEN 7. FIRST OF MAY 8. MORE THAN A WOMAN 9. LOVE SO RIGHT 10. NIGHT FEVER 11. WORDS 12. DON’T FORGET TO REMEMBER 13. IF I CAN’T HAVE YOU 14. ALONE 15. HEARTBREAKER 16. HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE 17. LOVE YOU INSIDE AND OUT 18. STAYIN’ ALIVE 19. BARKER OF THE UFO 20. SWAN SONG 21. SPICKS AND SPECKS Disc Two (Robin) 1. I AM THE WORLD 2. NEW YORK MINING DISASTER 3. I CAN’T SEE NOBODY 4. HOLIDAY 5. MASSACHUSETTS 6. SIR GEOFFREY SAVED THE WORLD 7. AND THE SUN WILL SHINE 8. THE SINGER SANG HIS SONG 9. I’VE GOTTA GET A MESSAGE TO YOU 10. I STARTED A JOKE 11. ODESSA 12. SAVED BY THE BELL – Robin Gibb 13. MY WORLD 14. RUN TO ME 15. LOVE ME 16. JULIET – Robin Gibb 17. THE LONGEST NIGHT 18. FALLEN ANGEL 19. RINGS AROUND THE MOON 20. EMBRACE 21. ISLANDS IN THE STREAM Disc Three (Maurice) 1. MAN IN THE MIDDLE 2. CLOSER THAN CLOSE 3. DIMENSIONS 4. HOUSE OF SHAME 5. SUDDENLY 6. RAILROAD 7. OVERNIGHT 8. IT’S JUST THE WAY 9. LAY IT ON ME 10. TRAFALGAR 11. OMEGA MAN 12. WALKING ON AIR 13. COUNTRY WOMAN 14. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I Would

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record and extend my indebtedness, sincerest gratitude and thanks to the following people: * Mr G J Bradshaw and Ms A Nel Weldrick for their professional assistance, guidance and patience throughout the course of this study. * My colleagues, Ms M M Khumalo, Mr I M Biyela and Mr L P Mafokoane for their guidance and inspiration which made the completion of this study possible. " Dr A A M Rossouw for the advice he provided during our lengthy interview and to Ms L Snodgrass, the Conflict Management Programme Co-ordinator. " Mrs Sue Jefferys (UPE) for typing and editing this work. " Unibank, Edu-Loan (C J de Swardt) and Vodakom for their financial assistance throughout this work. " My friends and neighbours who were always available when I needed them, and who assisted me through some very frustrating times. " And last and by no means least my wife, Nelisiwe and my three children, Mpendulo, Gabisile and Ntuthuko for their unconditional love, support and encouragement throughout the course of this study. Even though they were not practically involved in what I was doing, their support was always strong and motivating. DEDICATION To my late father, Enock Vumbu and my brother Gcina Esau. We Must always look to the future. Tomorrow is the time that gives a man or a country just one more chance. Tomorrow is the most important think in life. It comes into us very clean (Author unknow) ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF ABBREVIATIONS/ ACRONYMS USED ANC = African National Congress AZAPO = Azanian African Peoples -

Scoping Rogue River's Outstandingly Remarkable

SCOPING ROGUE RIVER’S OUTSTANDINGLY REMARKABLE VALUES Other Similar Values & Other River Values Mike Walker Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society Rogue Advocates Goal One Coalition Preliminary December 8, 2014 SCOPING ROGUE RIVER’S OUTSTANDINGLY REMARKABLE VALUES1 Other Similar Values & Other River Values Outline EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION PURPOSE I. HISTORICAL CHRONOLOGICAL ORV RECORD A. LEGISLATIVE INTENT 1958 Public Land Order (PLO) 1726 dated Sept 3, 1958. Oregon; 1959 PLO 1855 dated May 14, 1959 1961 Senate Select Committee on National Water Resources 1962 Outdoor Recreation for America by Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission 1963 Wild Rivers Study initiated by U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and U.S. Secretary of the Interior 1963 PLO 3165. July 31, 1963. Oregon; 1964 Draft Study Report of the Rogue River, Oregon, Pacific Southwest Reginal Task Force for Consideration of Wild Rivers Study Team. 1964 Wild Rivers Study 1965 Senate Bill S. 1446 by Interior and Insular Affairs Committee 1967 Senate Bill S. 119 by Interior and Insular Affairs Committee 1968 United States Congress. House. 1968. Report No. 1623. Providing for a National Scenic Rivers System and for Other Purposes. 1968 United States Congress. House. 1968. Report No. 1917. National Wild and Scenic Rivers System: Conference Report B. EARLY IMPLEMENTATION OF WILD & SCENIC RIVERS ACT 1968 The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (Public Law 90-542; 16 U.S.C. 1271 et seq.) 1969 Master Plan For The Rogue River Component Of The National Wild & Scenic Rivers System October 1969. USDI, Office of the Secretary. Washington, D.C. 1972 Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. -

Race, History and the Internet: the Use of the Internet in White Supremacist Propaganda in the Late 1990’S, with Particular Reference to South Africa

Race, History and the Internet: The use of the Internet in White Supremacist Propaganda in the late 1990’s, with particular reference to South Africa Inez Mary Stephney A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Wits School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg in fulfilment of the requirements for the Masters Degree. Abstract This dissertation aims to investigate the use of History by white supremacist groups in South Africa particularly, to rework their identity on the Internet. The disserta- tion argues that white supremacist groups use older traditions of history, particu- larly, in the South African case, the ‘sacred saga’, as explained by Dunbar Moodie to create a sense of historical continuity with the past and to forge an unbroken link to the present. The South African white supremacists have been influenced by the His- tory written by Van Jaarsveld for example, as will be shown in the chapters analysing the three chosen South African white supremacist groups. The white supremacists in the international arena also use history, mixed with 1930s Nazi propaganda to promote their ideas. i Acknowledgements There are a few people who must be acknowledged for their assistance during the research and preparation of this dissertation. First and foremost, my supervisor Dr Cynthia Kros for her invaluable advice and assistance- thank you. I also wish to thank Nina Lewin and Nicole Ulrich for all the encouragement, reading of drafts and all round unconditional love and friendship that has helped me keep it together, when this project seemed to flounder. Katie Mooney for saying I should just realised I am a historian and keep on going. -

Music to Move the Masses: Protest Music Of

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Music to Move the Masses: Protest Music of the 1980s as a Facilitator for Social Change in South Africa. Town Cape of Claudia Mohr University Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Music, University of Cape Town. P a g e | 1 A project such as this is a singular undertaking, not for the faint hearted, and would surely not be achieved without help. Having said this I must express my sincere gratitude to those that have helped me. To the University of Cape Town and the National Research Foundation, as Benjamin Franklin would say ‘time is money’, and indeed I would not have been able to spend the time writing this had I not been able to pay for it, so thank you for your contribution. To my supervisor, Sylvia Bruinders. Thank you for your patience and guidance, without which I would not have been able to curb my lyrical writing style into the semblance of academic writing. To Dr. Michael Drewett and Dr. Ingrid Byerly: although I haven’t met you personally, your work has served as an inspiration to me, and ITown thank you. -

The Psychological Impact of Guerrilla Warfare on the Boer Forces During the Anglo-Boer War

University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF GUERRILLA WARFARE ON THE BOER FORCES DURING THE ANGLO-BOER WAR by ANDREW JOHN MCLEOD Submitted as partial requirement for the degree DOCTOR PHILOSOPHIAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Human Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria 2004 Supervisor : Prof. F. Pretorius Co-supervisor : Prof. J.B. Schoeman University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) Abstract of: “The psychological impact of guerrilla warfare on the Boer forces during the Anglo- Boer War” The thesis is based on a multi disciplinary study involving both particulars regarding military history and certain psychological theories. In order to be able to discuss the psychological experiences of Boers during the guerrilla phase of the Anglo-Boer War, the first chapters of the thesis strive to provide the required background. Firstly an overview of the initial conventional phase of the war is furnished, followed by a discussion of certain psychological issues relevant to stress and methods of coping with stress. Subsequently, guerrilla warfare as a global concern is examined. A number of important events during the transitional stage, in other words, the period between conventional warfare and total guerrilla warfare, are considered followed by the regional details concerning the Boers’ plans for guerrilla warfare. These details include the ecological features, the socio-economic issues of that time and military information about the regions illustrating the dissimilarity and variety involved. In the chapters that follow the focus is concentrated on the psychological impact of the guerrilla war on the Boers. The wide range of stressors (factors inducing stress) are arranged according to certain topics: stress caused by military situations; stress caused by the loss of infrastructure in the republics; stress caused by environmental factors; stress arising from daily hardships; stress caused by anguish and finally stressors prompted by an individuals disposition.