Dynamic Aspects of Business Model Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reinforcing Work Motivation

J ÖNKÖPING I NTERNATIONAL B USINESS S CHOOL JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY Reinforcing Work Motivation - a perception study of ten of Sweden’s most successful and acknowledged leaders Master thesis within business administration Authors ©: Alexander Hall Niklas Nyman Tutor: Tomas Müllern Jönköping: September 2004 Master thesis within Business Administration Title: Reinforcing Work Motivation – a perception study of ten of Sweden’s most successful and acknowledged leaders Authors: Alexander Hall Niklas Nyman Tutor: Tomas Müllern Date: 2004-09-23 Subject terms: Work motivation, Work encouragement, Incentives, Intrinsic, Extrinsic, Rewards, Compensation, Praise, Delegation, Informa- tion-sharing, Communication, Productivity, Frontline Abstract Problem In pace with a noticeably fiercer global competition and an in- creased customer awareness, today’s organizations are faced with vast requirements for higher productivity and stronger customer- orientation. This transformation has denoted that human re- sources have become more and more accentuated, and a consen- sus has grown for the true power embraced within them. In Sweden, some few prominent leaders have distinguished them- selves by being highly successful in reinforcing employee motiva- tion, and their knowledge and experiences are priceless in the pursuit of utilizing the full potential of the workforce. Purpose The purpose with this thesis is to study how ten of Sweden’s most successful and acknowledged leaders view and work with employee motivation and critically examine their standpoints. The purpose is furthermore to exemplify how other leaders can strengthen employee motivation through adapting these motiva- tional suggestions. Method Qualitative cross-sectional interviews were conducted for the empirical research, holding a hermeneutic and inductive research approach. Respondents The respondent pool is comprised by both commercial leaders, as well as leaders from the world of sports. -

Stina Andersson Appointed EVP Strategy & Business Development

Tele2 AB Skeppsbron 18 P.O Box 2094 SE-103 13 Stockholm, Sweden Telephone +46 8 5620 0060 Fax: +46 8 5620 0040 www.tele2.com 2016-11-10 Stina Andersson appointed EVP Strategy & Business Development and new member of Tele2 AB’s Leadership Team Stockholm - Tele2 AB, (Tele2), (NASDAQ OMX Stockholm: TEL2 A and TEL2 B) today announces that Stina Andersson is appointed Executive Vice President Strategy & Business Development and member of Tele2 AB’s Leadership Team. Stina will own strategic planning and business development, for the group, including operational oversight of Tele2's IoT division. She will assume the position on 5 December 2016 and report to Allison Kirkby, President and CEO. Stina knows the Tele2 business well from her five years with Kinnevik, Tele2’s largest shareholder, where she most recently held the position of Investment Director and member of the Investment AB Kinnevik Management Team. Prior to this, Stina was Head of Strategy for Kinnevik, responsible for developing, executing, and sustaining corporate strategic initiatives involving Kinnevik’s largest holdings. Stina has also worked at McKinsey. She holds a Master of Science in Business and Economics from Stockholm School of Economics and a CEMS Master's in International Management from HEC Paris and Stockholm School of Economics. Allison Kirkby, President and CEO of Tele2 AB, comments: ”I am both proud and excited to have recruited such a great talent to Tele2 and our Leadership Team. Stina has exactly the qualities and experience we are looking for in this role, having delivered great results in her previous positions at Kinnevik and McKinsey. -

Biography of Jan Stenbeck - Google Search

biography of jan stenbeck - Google Search Sign in All Images News Videos Maps More Settings Tools About 24 700 results (0,52 seconds) Career. Stenbeck was born in Stockholm, Sweden, the youngest son of business lawyer Hugo Stenbeck (1890–1977) and his wife Märtha (née Odelfelt; 1906–1992). ... Control of the group was passed to his daughter Cristina Stenbeck after his death of a heart attack. Jan Stenbeck - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Stenbeck Biography About Featured Snippets Feedback Jan Hugo Robert Arne Stenbeck was a Swedish business leader, media Jan Stenbeck - Wikipedia pioneer, sailor and financier. He was https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Stenbeck head of Kinnevik Group from 1976 and Career. Stenbeck was born in Stockholm, Sweden, the youngest son of business lawyer Hugo founded among other things the Stenbeck (1890–1977) and his wife Märtha (née Odelfelt; 1906–1992). ... Control of the group companies Comviq, Invik & Co AB, was passed to his daughter Cristina Stenbeck after his death of a heart attack. Tele2, Banque Invik, Millicom, Modern Born: Jan Hugo Robert Arne Stenbeck; 14 Died: 19 August 2002 (aged 59); Paris, Times Group and NetCom Systems. Nov... France Wikipedia Born: November 14, 1942, Stockholm Jan Stenbeck – Wikipedia Died: August 19, 2002, American https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Stenbeck Translate this page Hospital of Paris, Neuilly-sur-Seine, Jan Stenbeck var yngste son till affärsadvokaten Hugo Stenbeck (1890–1977) och dennes France hustru Märta, född Odelfelt (1906–1992). Efter studentexamen vid ... Spouse: Merrill McLeod (m. Föräldrar: Hugo Stenbeck; Märta Odelfelt Styrelse- ledamot i: Investment AB Kinnevik, In.. -

Softathome Powers Boxer's Next Generation TV

SoftAtHome Powers Boxer’s Next Generation TV Nordic Operator Boxer Selects the SoftAtHome Operating Platform to Launch New Services Amsterdam, September 10th, 2010 - SoftAtHome, a software provider of home operating platforms that help Service Providers deliver convergent applications for the Digital Home, announced today that Boxer TV Access AB, the leading provider of terrestrial TV in the Nordic region, has selected the SoftAtHome Operating Platform to power its next generation TV offering including HDTV over DVB-T2 in combination with On Demand services over Internet. The two companies will collaborate to bring to market a next generation terrestrial offering and to enable the development of innovative features for Nordic subscribers. SoftAtHome provides an open, ubiquitous and carrier class software platform that enables Service Providers to create innovative and convergent applications for the Digital Home. It contains all the features and APIs necessary to create innovative and convergent applications. Service Providers and 3d party application developers can combine services such as voice, video, user interface, security, network access, connectivity or management, and deploy them across different devices in the home including Set Top Boxes (STB) and Home Gateways (HGW). “Boxer aims at providing access to a large number of paid and free to air terrestrial TV channels across the Nordic region. Our next generation TV offering will deliver a unique user experience on different types of STBs “, said Håkan Brander, Director Product Management & Development of Boxer. “We were looking for a solution that could provide a consistent user experience across different STBs. It was also key for Boxer to be able to find a software platform with the flexibility to develop the services of our choices today and in the future. -

Hur Digital-TV-Distributörer Bygger Relationer Med Kunder

Södertörns Högskola Institutionen för företagsekonomi och företagande Företagsekonomi, Kandidatuppsats 10 poäng Vårterminen 2006 Digital-TV Hur digital-TV-distributörer bygger relationer med kunder Författare: Clara Siwertz Stefan Tägt Handledare: Ted Modin i Sammanfattning 1997 kom riksdagen med ett förslag om att genomföra ett teknikskifte inom Sveriges marksända TV-distribution. Teknikskiftet skulle innebära att de analoga TV-sändningarna via marknätet skulle ersättas med digitala TV-sändningar och övergången skulle därför bidra med en mängd ekonomiska och tekniska fördelar. Digital-TV-sändningar erbjöds sedan tidigare av ett fåtal TV-distributörer men skulle nu bli något som fler TV-konsumenter skulle få tillgång till. Digital-TV-övergången är nu i full gång och påverkar såväl konsumenter som distributörer av digital-TV produkter och tjänster. Syftet med uppsatsen är att undersöka hur två digital-TV- distributörer anpassar sin marknadsföring för att stärka relationer till befintliga kunder och skapa relationer till nya kunder. Uppsatsen fokuserar på huruvida distributörerna tillämpar transaktionsmarknadsföring eller relationsmarknadsföring och hur den rådande digital-TV- övergången påverkar marknadsföringen. Teorier bakom relationsmarknadsföring fokuserar bland annat på relationen mellan leverantör och kund och detta är det centrala temat i uppsatsen. Värdeskapande, involvering, anpassningsförmåga, informationshantering, kundvård och CRM är några av de saker som studeras på respektive företag. Canal Digital AB och Boxer TV Access AB är de två distributörerna som undersöks och uppsatsen avgränsas till deras verksamhet i Sverige. Resultatet av undersökningen tyder på att distributörerna är väl medvetna om vikten av relationen till deras kunder. Flera exempel visar på att företagen arbetar aktivt för att vårda befintliga kunder och dessutom skapa nya relationer med kunder. -

Antavla För Jan Stenbeck

SYSSLINGEN Medlemsblad 3, 2014 Årgång 21 Ordföranden har ordet Säg den glädje som varar beständigt! När ni läser detta är snart denna fantastiska sommar slut. Lagom till midsommar avslutades mitt arbete med nya dödskivan, så jag kunde med gott samvete ägna mig åt att besöka ÅF Offshore Race inne på Skeppsholmen. Det är en fantastisk upplevelse att se alla dessa segelbåtar mitt inne i Stockholm. Särskild imponerande är den s k ”Antikrundan” med Salén Ballad, Wallenbergs Regina m fl fina mahognybåtar. Veckan därpå slog värmen till och jag har tillbringat en stor del av sommaren på Trovillestranden i Sandhamn. Jag har badat så mycket att jag börjar bli rädd att få simhud mellan tårna. Nu är det dags att återvända till verkligheten: lördagen den 16 augusti medverkade vår förening vid skärgårdsmarkanden i Vaxholm, den 29-31 augusti är det dags för släktforskardagarna i Karlstad och lördagen den 6 september kommer vi att sitta släktforskarjour på Vaxholms stadsbibliotek un- der en Kulturdag som kommer att arrangeras i Vaxholm. För övrigt fortsätter vi med vår jourverk- samhet på biblioteken i Vaxholm och Åkersberga varje lördag kl 11-13. Välkomna till en ny släktforskarhöst! Anita Järvenpää Föreningens adress: Medlemstidningen Sysslingen utkommer med 4 nr/år Bidrag kan sändas till redaktören, Susanne Fagerqvist, Guckuskovägen 12, Murkelvägen 137, 184 34 Åkersberga, tel 08-540 653 26 184 35 Åkersberga Ansvarig utgivare: Anita Järvenpää E-post: [email protected], eller Styrelse: [email protected] Ordförande Anita Järvenpää 08-541 338 19 Hemsida: www.roslagen.be e-post: [email protected] Hemsideskonstruktör: Olle Keijser Sekreterare Carl-Göran Backgård 08-540 611 36 e-post: [email protected] För signerade bidrag ansvarar författaren. -

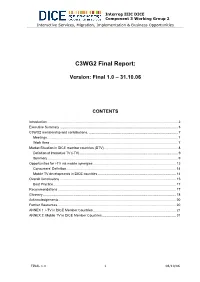

C2WG3 Progress Report

Interreg IIIC DICE Component 3 Working Group 2 Interactive Services, Migration, Implementation & Business Opportunities C3WG2 Final Report: Version: Final 1.0 – 31.10.06 CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 C3WG2 membership and contributions. ................................................................................................ 7 Meetings............................................................................................................................................. 7 Work Area .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Market Situation in DICE member countries (DTV) ............................................................................... 8 Definition of Interactive TV (i-TV).......................................................................................................... 9 Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Opportunities for i-TV via mobile synergies ......................................................................................... 13 Consumers’ Definition..................................................................................................................... -

Information to Shareholders in Investment AB Kinnevik (Publ) Prior to the Extraordinary General Meeting to Be Held on 11 May 2009

Information to shareholders in Investment AB Kinnevik (publ) prior to the Extraordinary General Meeting to be held on 11 May 2009 Acquisition of Emesco AB Table of Contents Background and Reasons for the Transaction............................................................................... 3 Emesco................................................................................................................................................ 4 The Transaction ................................................................................................................................. 5 Effects of the Transaction on Kinnevik ........................................................................................... 7 Summary of the Transaction Agreement......................................................................................... 9 Fairness Opinions............................................................................................................................ 13 Extraordinary General Meeting, 11 May 2009 The Board of Directors of Investment AB Kinnevik (publ) (“Kinnevik”) proposes that the shareholders in Kinnevik at the Extraordinary General Meeting (“EGM”) to be held on Monday 11 May 2009 at 11.00 am CET after the Annual General Meeting (“AGM”), approves the acquisition of all shares in Emesco AB (“Emesco”). For information regarding participation at the EGM, see the notice to the EGM available at www.kinnevik.se. This information brochure has been prepared to provide information for the shareholders in Kinnevik -

Tele2 AB Skeppsbron 18 P.O Box 2094 SE-103 13 Stockholm, Sweden Telephone +46 8 5620 0060 Fax: +46 8 5620 0040 2017-12-15

Tele2 AB Skeppsbron 18 P.O Box 2094 SE-103 13 Stockholm, Sweden Telephone +46 8 5620 0060 Fax: +46 8 5620 0040 www.tele2.com 2017-12-15 Tele2: The Nomination Committee proposes the election of Georgi Ganev as new Chairman of the Board Stockholm – Tele2 Group (Tele2), (NASDAQ Stockholm Exchange: TEL2 A and TEL2 B) today announced that its Nomination Committee will propose the election of Georgi Ganev as new Chairman of the Board, and that Mike Parton and Irina Hemmers will decline re-election, at the Annual General Meeting 2018. Georgi Ganev has been a Director of the Board of Tele2 since 2016. At the Annual General Meeting 2018, he will succeed Mike Parton, who, along with Irina Hemmers, has informed the Nomination Committee of their intention not to stand for re-election. Cristina Stenbeck, Chairman of the Nomination Committee, said: “The Nomination Committee is pleased to propose the election of Georgi Ganev as new Chairman of Tele2. In Georgi, Tele2 will have a Chairman with solid experience from the Nordic TMT sector, and a keen appreciation of the company’s future opportunities.” Cristina Stenbeck continued: “On behalf of the Nomination Committee, I would like to extend our deepest gratitude to Mike Parton for his significant contribution during a successful eleven-year tenure on the Tele2 Board, and to Irina Hemmers who have brought valuable perspectives to the Board’s discussions since her election in 2014.” Mike Parton said: “As I have been a Board member for eleven years, eight as Chairman, and the company’s performance is going from strength to strength, the Nomination Committee and I feel now is the appropriate time for me to step down. -

Digital-Tv-Kommissionens Slutrapport, KU 2004:04

I den här slutrapporten från Digital-tv-kommissionen beskrivs • Informationsmodellen – en kampanjstomme bestående av DR, planering och genomförande av den svenska digital-tv-övergången. annonsering och lokala möten har successivt rullats ut lokalt i Som ett av världens första länder genomförde Sverige 2004-2008 landet i takt med att övergången har nått nya områden. ett teknikskifte som direkt eller indirekt berörde drygt 4 miljoner • Nedsläckningsstrategin – modellen med en gradvis övergång hushåll. Lärdomarna är många och de fyra enskilt viktigaste fram- genom Sverige har inneburit möjlighet till lokalanpassade informa- gångsfaktorerna är: tionsaktiviteter och kontinuerlig utveckling av produktutbudet. • Samarbetet – genomförandet av övergången har byggt på en Digital-tv-kommissionen hoppas att denna slutrapport ska kunna framgångsrik samarbetsmodell mellan de inblandade huvudaktö- bidra med viktiga erfarenheter och kunskap inför liknande projekt rerna: Digital-tv-kommissionen, Teracom, SVT och TV4. både inom och utanför Sverige. • Varumärket – det gemensamma varumärket ”Digital-tv-övergången” har bidragit till fokus och en tydlig avsändare för projektet. SLU T- RAPPORT Digital-tv-kommissionens slutrapport, KU 2004:04 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010 101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 -

Tidning Förelektronikbranschen

NR 10/2007 ÅRGÅNG 53 PRIS 60 KR TIDNING FÖR ELEKTRONIKBRANSCHEN EXKL MOMS High Defi like no other no like Beskåda dina bilder på en BRAVIA eller VAIO iFullHD1080. ellerVAIO Beskåda dinabilderpåenBRAVIA baksidan. Steady shotochenstor3-tumsLCD-displaypå med 5bilderisekunden,RAW-format,bildstabilisatorSuper rahus imagnesiumlegering.Hela12megapixlar,seriebildstagning Sonys nyasystemkameramedettdamm-ochfuktskyddatkame- High Definition • 3”LCDmed921000pixlar • FullHDupplösningmedHDMI-utgång • SuperSteadyShot • 12.24megapixelCMOSsensor SONY SONY 700 nition PROJECTORPROJECTOR VAIOVAIO BRAVIA RATEKO INNEHÅLL 10/2007 46 12 VILL BEHÅLLA MARKNÄTET TILL TV Europas TV-industri vill behålla marknätets frekvenser till HDTV-sändningar och utestänga telekomindustrin. 14 VÄRLDENS FÖRSTA BLU-RAY-KAMEROR Hitachi presenterade på IFA världens första Blu-ray- 14 kameror. Men IFA innehöll många andra nyheter. 82 46 TIO FRÅGOR TILL SONNY FJELLSTRÖM Om två år funderar Sonny Fjellström i Uppsala på att sälja Allradio och istället segla jorden runt. 52 NIKON HAR LANSERAT NYTT FLAGGSKEPP 23 augusti lanserade Nikon sitt nya fl aggskepp D3, en kamera med fullstor sensor och 12 megapixel. 60 SONYS NYA SEMIPROFFSKAMERA I vykortsvackra italienska alperna valde Sony att lansera 52 nya semiproffskameran Į700. 60 64 NY VD PÅ AUDIOVIDEO Johan Danielsson tar över VD-tjänsten på Audiovideo efter Werner Leyh från 1 november. NR 10/2007 ÅRGÅNG 53 PRIS 60 KR TIDNING FÖR ELEKTRONIKBRANSCHEN EXKL MOMS 70 KANONRESULTAT AV RICHARD BÄCKMAN Richard Bäckman slog till i B-klassen med 42 poäng och Linus Johansson vann A-klassen av Radiogolfen. 72 ÅTERLANSERING AV SIDEWINDER Microsoft återlanserar Sidewinder och återuppväcker därmed produktlinjen från 1995-2003. 82 ÖVER 20 MILJONER PIXLAR Canon förstärker sin professionella serie digitala system- 64 kameror med EOS 1DsMkIII med 21 megapixels. -

Freedom of the Press 2007

FREEDOM OF THE PRESS 2007 needs updating FREEDOM OF THE PRESS 2007 A Global Survey of Media Independence EDITED BY KARIN DEUTSCH KARLEKAR AND ELEANOR MARCHANT FREEDOM HOUSE NEW YORK WASHINGTON, D.C. ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. LANHAM BOULDER NEW YORK TORONTO PLYMOUTH, UK ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, MD 20706 www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2007 by Freedom House All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISSN 1551-9163 ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5435-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-7425-5435-X (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-5436-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-7425-5436-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Table of Contents Acknowledgments, vii The Survey Team, ix Survey Methodology, xix Press Freedom in 2006, 1 Karin Deutsch Karlekar Global and Regional Tables, 17 Muzzling the Media: The Return of Censorship in the Common- wealth of Independent States, 27 Christopher Walker Country Reports and Ratings, 45 Freedom House Board of Trustees, 334 About Freedom House, 335 Acknowledgments Freedom of the Press 2007 could not have been completed without the contributions of numerous Freedom House staff and consultants.