Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Newsletter

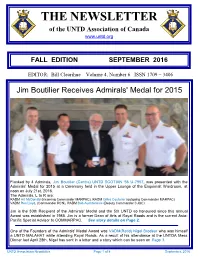

THE NEWSLETTER of the UNTD Association of Canada www.untd.org FALL EDITION SEPTEMBER 2016 EDITOR: Bill Clearihue Volume 4, Number 6 ISSN 1709 – 3406 Jim Boutilier Receives Admirals' Medal for 2015 Flanked by 4 Admirals, Jim Boutilier (Centre) UNTD SCOTIAN '56 U-7957, was presented with the Admirals' Medal for 2015 at a Ceremony held in the Upper Lounge of the Esquimalt Wardroom, at noon on July 21st, 2016. The Admirals, L to R are: RADM Art McDonald (incoming Commander MARPAC), RADM Gilles Couturier (outgoing Commander MARPAC) VADM Ron Lloyd, (Commander RCN), RADM Bob Auchterlonie (Deputy Commander CJOC) Jim is the 30th Recipient of the Admirals' Medal and the 5th UNTD so honoured since this annual Award was established in 1985. Jim is a former Dean of Arts at Royal Roads and is the current Asia- Pacific Special Advisor to COMMARPAC. See story details on Page 2. One of the Founders of the Admirals' Medal Award was VADM(Ret'd) Nigel Brodeur who was himself a UNTD MALAHAT while attending Royal Roads. As a result of his attendance at the UNTDA Mess Dinner last April 28th, Nigel has sent in a letter and a story which can be seen on Page 3. UNTD Association Newsletter Page 1 of 8 September, 2016 Jim Boutilier Receives Admirals' Medal for 2015 Jim Boutilier Receives Admirals' Medal for 2015 - cont'd It was originally planned that Jim would formally receive this Jim has a well earned reputation for speaking eloquently and prestigious award from VADM Mark Norman, Commander RCN, incisively, reducing complex issues to their core, much to the at the NAC's Annual Battle of the Atlantic Gala Dinner, which was appreciation of and distinct advantage to his audiences. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS David B. Quinn. European Approaches to North analyse social and demographic trends and so America, 1450-1640. Variorum Collected Studies; have been unfashionable for more than a decade" Aldershot and Brookfield, VT: Variorum Press, (221). It is, however, useful for historians and 1998. x + 342 pp., illustrations, maps, charts, others interested in the past to know what hap• index. US $101.95, cloth; ISBN 0-86078-769-9. pened, or at least what is likely to have happened. Quinn may be no exponent of the latest Paris fad This most recent collection of David Quinn's but he remains a scholar whose interpretation of essays on the early European exploration and events inevitably commands respect, precisely settlement of North America follows his Explor• because he is always more interested in making ers and Colonies: America, 1500-1625 (London, sense of the document than in validating a theo• 1990). Like its useful predecessor, European retical preconception. Approaches brings together Quinn's contributions What of the longer essays in this volume, in to several disparate publications. Although most which Quinn cautiously dons the unfamiliar of the essays in the present volume have appeared analytic robe? "Englishmen and Others" is a blunt in scholarly journals or conference proceedings and therefore interesting assessment of how since the late 1980s, that previous exposure does Quinn's compatriots viewed themselves and other not detract from the usefulness of this book. The Europeans on the eve of colonization. The final topics range from imagined Atlantic islands, to essay, "Settlement Patterns in Early Modern perceptions of American ecology, the French fur Colonization," is an analysis of the state of early trade, the settlement of Bermuda, editing Hakluyt, European colonization by 1700. -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and Life in the West Coast Reserve Fleet, 1913-1918

Canadian Military History Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 2 2010 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Richard O. Mayne "“For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918." Canadian Military History 19, 1 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne n 30 October 1918, Arthur for all activities related to Canada’s Ashdown Green, a wireless Abstract: HMCS Galiano is remembered oceans and inland waters including O mainly for being the Royal Canadian operator on Triangle Island, British Navy’s only loss during the First World the maintenance of navigation Columbia, received a bone-chilling War. However, a close examination aids, enforcement of regulations signal from a foundering ship. of this ship’s history not only reveals and the upkeep of hydrographical “Hold’s full of water,” Michael John important insights into the origins and requirements. Protecting Canadian identity of the West Coast’s seagoing Neary, the ship’s wireless operator sovereignty and fisheries was also naval reserve, but also the hazards and desperately transmitted, “For God’s navigational challenges that confronted one of the department’s key roles, Sake send help.” Nothing further the men who served in these waters. -

UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER December 2011

OUR CREED: To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its constitution. UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER December 2011 1 Picture of the Month………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Members…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Honorary Members……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Meeting Attendees………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….5 Old Business….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 New Business…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Good of the Order……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Base Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Birthdays……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Welcome…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Binnacle List……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………,…8 Quote of the Month.……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…8 Fernando Igleasis Eternal Patrol…………………………………………………………………………………………………9 Robert Gibbs’ Memorial……………..….…………………..……………………………………………………………………10 Lexington Veteran’s Day Parade………………………………………………………………………………………………12 Columbia Veteran’s Day Parade.………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Dates in American Naval History………………………………………………………………………………………………16 Dates in U.S. Submarine History………………………………………………………………………………………………22 -

100 Years of Submarines in the RCN!

Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ Volume VII, No. 65 ~ Winter 2013-14 Public Archives of Canada 100 years of submarines in the RCN! National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca Please help us put printing and postage costs to more efficient use by opting not to receive a printed copy of Starshell, choosing instead to read the FULL COLOUR PDF e-version posted on our web site at http:www.nava- Winter 2013-14 lassoc.ca/starshell When each issue is posted, a notice will | Starshell be sent to all Branch Presidents asking them to notify their ISSN 1191-1166 members accordingly. You will also find back issues posted there. To opt out of the printed copy in favour of reading National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Starshell the e-Starshell version on our website, please contact the Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada Executive Director at [email protected] today. Thanks! www.navalassoc.ca PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh OUR COVER RCN SUBMARINE CENTENNIAL HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele The two RCN H-Class submarines CH14 and CH15 dressed overall, ca. 1920-22. Built in the US, they were offered to the • RCN by the Admiralty as they were surplus to British needs. PRESIDENT Jim Carruthers, [email protected] See: “100 Years of Submarines in the RCN” beginning on page 4. PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] TREASURER • Derek Greer, [email protected] IN THIS EDITION BOARD MEMBERS • Branch Presidents NAVAL AFFAIRS • Richard Archer, [email protected] 4 100 Years of Submarines in the RCN HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Page Certificate of Examination I

The End of the Big Ship Navy: The Trudeau Government, the Defence Policy Review and the Decommissioning of the HMCS Bonaventure by Hugh Avi Gordon B.A.H., Queen’s University at Kingston, 2001. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ______________________________________________________________ Dr. D.K. Zimmerman, Supervisor (Department of History) ______________________________________________________________ Dr. P.E. Roy, Departmental Member (Department of History) ______________________________________________________________ Dr. E.W. Sager, Departmental Member (Department of History) ______________________________________________________________ Dr. J.A. Boutilier, External Examiner (Department of National Defence) © Hugh Avi Gordon, 2003 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisor: Dr. David Zimmerman ABSTRACT As part of a major defence review meant to streamline and re-prioritize the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), in 1969, the Trudeau government decommissioned Canada’s last aircraft carrier, HMCS Bonaventure. The carrier represented a major part of Maritime Command’s NATO oriented anti- submarine warfare (ASW) effort. There were three main reasons for the government’s decision. First, the carrier’s yearly cost of $20 million was too much for the government to afford. Second, several defence experts challenged the ability of the Bonaventure to fulfill its ASW role. Third, members of the government and sections of the public believed that an aircraft carrier was a luxury that Canada did not require for its defence. There was a perception that the carrier was the wrong ship used for the wrong role. -

Harry George Dewolf 1903 - 2000

The Poppy Design is a registered trademark of The Royal Canadian Legion, Dominion Command and is used under licence. Le coquelicot est une marque de commerce enregistrée de La Direction nationale de La Légion royale canadienne, employée Le coquelicot est une marque de commerce enregistrée La Direction nationale sous licence. de La Légion royale canadienne, Dominion Command and is used under licence. The Royal Canadian Legion, Design is a registered trademark of The Poppy © DeWolf family collection - Collection de la famille DeWolf © DeWolf HARRY GEORGE DEWOLF 1903 - 2000 HOMETOWN HERO HÉROS DE CHEZ NOUS Born in Bedford, Nova Scotia, Harry DeWolf developed a passion for Originaire de Bedford en Nouvelle-Écosse, Harry DeWolf se passionne pour the sea as a youth by sailing in Halifax Harbour and Bedford Basin, later la mer dès sa jeunesse en naviguant dans le port d’Halifax et le bassin de pursuing a 42-year career in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). Bedford, ce qui l’amènera à poursuivre une carrière de 42 ans au sein de la Marine royale du Canada (MRC). During the Second World War, he earned a reputation as a skilled, courageous officer. As captain of HMCS St Laurent, in 1940 DeWolf Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il se fait une réputation d’officier ordered the RCN’s first shots fired during the early stages of the war. de marine compétent et courageux. À la barre du NCSM St Laurent en CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military© Image Museum 2011.022.012 courtesy of the Beament collection, © Image Collection Beanment 2011.022.012 avec l’aimable autorisation du Musée naval et militaire de la BFC Esquimalt, He led one of the largest rescues when his ship saved more than 850 1940, DeWolf ordonne les premiers tirs de la MRC au début de la guerre. -

The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2020 A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983 Garison Ma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Political History Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Ma, Garison, "A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983" (2020). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 2330. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983 by Garison Ma BA History, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2018 THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of History in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Master of Arts in History Wilfrid Laurier University © Garison Ma 2020 To my parents, Gary and Eppie and my little brother, Edgar. II Abstract In December 1977, the Liberal government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau authorized the Department of National Defence (DND) to begin the acquisition of new warships for the navy. The decision to acquire fully combat capable warships was a shocking decision which marked the conclusion of a remarkable turnaround in Canadian defence policy. -

Post-Somalia Reform in the Canadian Armed Forces: Leadership, Education, and Professional Development

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-12-10 Post-Somalia Reform in the Canadian Armed Forces: Leadership, Education, and Professional Development Domansky, Katie Domansky, K. (2018). Post-Somalia Reform in the Canadian Armed Forces: Leadership, Education, and Professional Development (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/34926 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109304 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Post-Somalia Reform in the Canadian Armed Forces: Leadership, Education, and Professional Development by Katie Domansky A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, 2018 © Katie Domansky 2018 ABSTRACT After the “Somalia Affair” of the early 1990s, a government investigation concluded that the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) had become dysfunctional as a professional military force and needed to be comprehensively reformed. It was perceived to -

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 72, Autumn 2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… The Kingston-class Maritime Coastal Defence Vessel (MCDV) HMCS Whitehorse conducts maneuverability exercises off the west coast. NAVAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA ASSOCIATION NAVALE DU CANADA (See: “One Navy and the Naval Reserve” beginning on page 9.) Royal Canadian Navy photo. Starshell ISSN-1191-1166 In this edition… National magazine of the Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada From the Editor 4 www.navalassoc.ca From the Front Desk 4 PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh NAC Regalia Sales 5 HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele From the Bridge 6 PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] Maritime Affairs: “Another Step Forward” 8 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] One Navy and Naval Reserve 9 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] NORPLOY ‘74 12 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] Mail Call 18 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. Alec Douglas, [email protected] The Briefing Room 18 HONORARY COUNSEL • Donald Grant, [email protected] Schober’s Quiz #69 20 ARCHIVIST • Fred Herrndorf, [email protected] This Will Have to Do – Part 9 – RAdm Welland’s Memoirs 20 AUSN LIAISON • Fred F.