Teaching Unions – Splits, Mergers, Alliances and Community Identity 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Policy Guide 2019

National Policy Guide 2019 Incorporating the decisions of Congress 2018 KEY symbol signifies where a CEC Statement or CEC Special Report has been agreed by Congress. Please refer to those documents for more detail. (2016: C1) where references are given, the first part represents the Congress year and the latter the motion or composite (so this refers to Composite 1 from GMB Congress 2016) All Congress documents from 2005 onwards can be found on the GMB website at www.gmb.org.uk/congress Background GMB Annual Congress is the supreme policy making authority of GMB. It deals with motions and rule amendments from GMB Branches, Regional Committees and the Central Executive Council (CEC). In addition, other issues such as CEC special reports, CEC Statements and Financial Reports are debated and voted on. Once these have been endorsed, they become GMB Policy for the union as a whole. Following the endorsement of the CEC Special Report ‘Framework for the Future of the GMB: Moving Forward’ at Congress 2007, it was agreed that Congress will not debate motions which are determined to be existing union policy. At its meetings prior to Congress, the CEC identifies those Congress motions which are in line with existing GMB policy. These recommendations are reported to Congress in SOC Report No 1 at the start of Congress. Delegates will be asked to endorse these motions and if agreed, the motions will not be debated. However following Congress progress on these motions will continue to be reported. The following guide is an indication of GMB policy but is not a definitive list. -

Beat the Credit Crunch with Alvin’S Stardust

learthe ni ng rep » Winter 2010 Viva the revolution! Festival promotes informal learning Welcome to No 10 … Apprentices meet their own minister Teaching the teachers Unions help combat bad behaviour Quick Reads exclusive Beat the credit crunch with Alvin’s stardust www.unionlearn.org.uk » Comment A celebration of 49 apprenticeships Last month unionlearn was at 10 Downing Street to celebrate apprenticeships. A packed event saw apprentices from a range of backgrounds and from a range of unions mixing with guests and ministers. The enjoyable and inspiring evening showed off the benefits of apprenticeships and brought together some exceptional young people. Three of the apprentices (Adam Matthews from the PFA and Cardiff City FC; Leanne Talent from UNISON and Merseytravel; Richard Sagar from Unite and Eden Electrics) addressed the audience and impressed everyone there. A big thank to them for their professionalism and eloquence when speaking on the day. 10 14 A thank you too to ministers Kevin Brennan, Pat McFadden and Iain Wright for joining us, as well as Children’s Secretary Ed Balls and 16 Business Secretary Lord Mandelson. A strong commitment to support and expand apprentices was given by Gordon Brown, which was warmly welcomed by all those there. In this issue of The Learning Rep , you will find a full report of the Downing Street event with some great photographs of the apprentices. 18 28 We’ve decided to make this issue an apprentices special and it includes interviews with Richard, Leanne and Adam who spoke at the Downing Contents: Street event as well as an interview with Kevin 3 24 Brennan, the apprentices minister. -

Download Issue 27 As

Policy & Practice A Development Education Review ISSN: 1748-135X Editor: Stephen McCloskey "The views expressed herein are those of individual authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of Irish Aid." © Centre for Global Education 2018 The Centre for Global Education is accepted as a charity by Inland Revenue under reference number XR73713 and is a Company Limited by Guarantee Number 25290 Contents Editorial Rethinking Critical Approaches to Global and Development Education Sharon Stein 1 Focus Critical History Matters: Understanding Development Education in Ireland Today through the Lens of the Past Eilish Dillon 14 Illuminating the Exploration of Conflict through the Lens of Global Citizenship Education Benjamin Mallon 37 Justice Dialogue for Grassroots Transition Eilish Rooney 70 Perspectives Supporting Schools to Teach about Refugees and Asylum-Seekers Liz Hibberd 94 Empowering more Proactive Citizens through Development Education: The Results of Three Learning Practices Developed in Higher Education Sandra Saúde, Ana Paula Zarcos & Albertina Raposo 109 Nailing our Development Education Flag to the Mast and Flying it High Gertrude Cotter 127 Global Education Can Foster the Vision and Ethos of Catholic Secondary Schools in Ireland Anne Payne 142 Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review i |P a g e Joining the Dots: Connecting Change, Post-Primary Development Education, Initial Teacher Education and an Inter-Disciplinary Cross-Curricular Context Nigel Quirke-Bolt and Gerry Jeffers 163 Viewpoint The Communist -

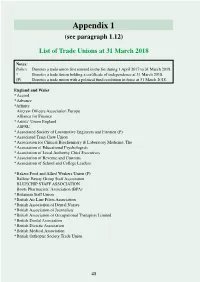

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

The Community Organizing Toolbox

COMMUNITY ORGANIZING A Funder’s Guide to Community Organizing TOOLBOXNeighborhood Funders Group COMMUNITY ORGANIZING TOOLBOX By Larry Parachini and Sally Covington April 2001 Neighborhood Funders Group One Dupont Circle Suite 700 Washington, DC 20036 202-833-4690 202-833-4694 fax E-mail [email protected] Web site: www.nfg.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . 2 Introduction . 3 Why a CO Toolbox? . 5 NFG’s Objectives for the Toolbox. 6 Organization of the Toolbox . 6 How to Use the Toolbox . 7 Community Organizing: The Basics . 9 What is CO? . 11 Case Study #1: Southern Echo . 14 A Brief History of CO . 16 Leadership and Participation: How CO Groups Work . 20 Case Study #2: Lyndale Neighborhood Association . 21 Community Organizers: Who are They? . 22 Types of CO Groups and the Work They Do . 25 Case Study #3: Pacific Institute for Community Organization (PICO) . 30 How National and Regional Networks Provide Training, Technical Assistance and Other Support for CO . 31 Case Study #4: Developing a Faith-Based CO Organization . 32 CO Accomplishments . 33 Case Study # 5: An Emerging Partnership Between Labor and CO . 36 The Promise of Community Organizing . 40 Grantmakers and Community Organizing . 43 Issues to Consider at the Start . 45 CO Grantmaking and NFG’s Mission . 46 Case Study #6: A Funder’s Advice on Dispelling the Myths of CO. 47 Why Grantmakers Prioritize CO . 49 Case Study #7: Rebuilding Communities Initiative . 53 Determining an Overall CO Grantmaking Strategy . 54 Case Study #8: The James Irvine Foundation . 55 Funding Opportunities in the CO Field . 57 Case Study #9: The Toledo/Needmor CO Project . -

'Sharing the Future' Report Here

SUMMARY REPORT SHARING THE FUTURE WORKERS AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE 2020S Summary of the final report of the Commission on Workers and Technology The Changing Work Centre was established by the Fabian Society and the trade union Community in February 2016 to explore progressive ideas for the modern world of work. Through in-house and commissioned research and events, the centre is looking at the changing world of work, attitudes towards it and how the left should respond. The centre is chaired by Yvette Cooper MP and supported by an advisory panel of experts and politicians. Community is a modern trade union with over a hundred years’ experience standing up for working people. With roots in traditional industries, Community now represents workers across the UK in various sectors. The Fabian Society is an independent left-leaning think tank and a democratic membership society with 8,000 members. A Community and Fabian Society report This report represents not the collective Community general views of Community and the Fabian secretary: Roy Rickhuss Society, but only the views of the individual Fabian Society general commissioners and authors. The responsibility secretary: Andrew Harrop of the publishers is limited to approving its publications as worthy of consideration within the labour movement. First published in December 2020 Cover image © Johavel vector/Shutterstock. 2 / Summary report The Commission on Workers and Technology CONTENTS was established in August 2018 by Community and the Fabian Society. It was chaired by Rt Hon 4 Introduction Yvette Cooper MP who led the commission’s work across its life. The other commissioners were Hasan 7 Chapter one: Bakhshi, Sue Ferns, Paul Nowak, Katie O’Donovan, The Covid-19 crisis Roy Rickhuss and Professor Margaret Stevens. -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland 2019-2020

2019-2020 Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland (Covering Period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020). 10-16 Gordon Street Process Colour C: 60 M: 100 Y: 0 Belfast BT1 2LG K: 40 Tel: 028 9023 7773 Pantone Colour 260 Process Colour C: 21 Email: [email protected] M: 26 Y: 61 K: 0 Web: www.nicertoffice.org.uk Pantone Colour 111 TYPEFACE : HELVETICA NEUE First published February 2021 CERTIFICATION OFFICER FOR NORTHERN IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Laid before the Northern Ireland Assembly under paragraph 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 by the Department for the Economy Mr Mike Brennan Permanent Secretary Department for the Economy Netherleigh House Massey Avenue BELFAST BT4 2JP I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 2 Mrs Marie Mallon Chair Labour Relations Agency 2-16 Gordon Street BELFAST BT1 2LG I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 3 CONTENTS Review of the year A summary from the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland . -

Give Us What We Deserve Taking to the Streets for SEND Funding

Willow’s Windrush nightmare Families at breaking point Windy City victories TA sacked due to hostile The impact of knife crime on Chicago teachers on the gains environment. See page 19. our communities. See page 26. of recent strikes. See page 37. July/ August 2019 Your magazine from the National Education Union Give us what we deserve Taking to the streets for SEND funding. See page 7 END OF TERM PREVIEWS FOR SCHOOLS TO ARRANGE A SPECIAL END OF TERM PREVIEW SCREENING* CONTACT [email protected] WITH AND EMILIA SEBASTIAN NICK CRAIG KATE RUPERT ALEX LEE WARWICK SANJEEV ALEXANDER CHRIS DEREK KIM JONES CROFT FROST ROBERTS NASH GRAVES MACQUEEN MACK DAVIS BHASKAR ARMSTRONG ADDISON JACOBI CATTRALL ARE YOUR STUDENTS #TEAMROMAN OR #TEAMCELT? REGISTER FOR A FUN & FREE LEARNING RESOURCE FROM INTO FILM AT WWW.INTOFILM.ORG/HORRIBLE-HISTORIES IN CINEMAS JULY 26 *PREVIEW SCREENING OFFER AVAILABLE FROM MONDAY JULY 8TH ONWARDS. HORRIBLEHISTORIES.MOVIE HORRIBLEHISTORIESTHEMOVIE Educate July/August 2019 Welcome Protestors at the SEND National Crisis demonstration. Photo: Rehan Jamil Willow’s Windrush nightmare Families at breaking point Windy City victories AS Educate goes to press, members of the Conservative Party are still deciding TA sacked due to hostile The impact of knife crime on Chicago teachers on the gains environment. See page 19. our communities. See page 26. of recent strikes. See page 37. who will become the country’s next Prime Minister. July/ August 2019 The fact that candidates in the Tory leadership election have raised the issue of school funding is testament to all the hard work of campaigners to get Your magazine from the National Education Union this issue on the political agenda. -

Our Hero Child Poverty and Marcus Rashford’S Fight for Free Holiday School Meals

Testing times Defend disabled members End period poverty Demanding school safety Ensuring protection for Free sanitary products during Covid-19. See page 6. at-risk educators. See page 22. in schools. See page 26. November/ December 2020 Your magazine from the National Education Union Our hero Child poverty and Marcus Rashford’s fight for free holiday school meals TUC best membership communication print journal 2019 Meeting your School’s Literacy Needs with Expert Training from CLPE Deepen your subject knowledge with CLPE’s professional courses The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) is an independent UK charity dedicated to raising the literacy achievement of children by putting quality literature at the heart of all learning. 100% 100% 99% Inspires the teacher. of people attending of people attending of people attending Inspires a class. The best our day courses our long courses our day courses would recommend rated the training rated their course course I’ve been on. it to someone else as eff ective as eff ective TEACHER ON CLPE TRAINING, 2019 NEW Online Learning from CLPE Our expert teaching team have developed a programme of online learning to provide extra support for your literacy curriculum. The programme will provide staff with evidence based professional development drawing on learning from CLPE’s research and face to face teaching programmes including: • The CLPE Approach to teaching literacy: Using high quality texts at the heart of the curriculum • CLPE Research and Subject Knowledge Series: Planning eff ective provision to ensure progress in reading and writing • Power of Reading Training Online: Developing a broad, rich book based English curriculum across your school This programme of learning will give primary teachers the opportunity to explore CLPE’s high-impact professional development online. -

Rule Book – Effective from Rules Conference 2015 (P.June.18)

UNITE RULE BOOK – EFFECTIVE FROM RULES CONFERENCE 2015 (P.JUNE.18) Rule Book Effective from Rules Conference 2015 Revised and re-printed June 2018 General Secretary: Len McCluskey Chair, Executive Council: Tony Woodhouse www.unitetheunion.org (JN8359) IDGB/06/18 14245 Unite Rule Book Cover GB 4th June 2018.indd 1 04/06/2018 13:55 UNITE RULE BOOK CONTENTS RULE 1 TITLE AND REGISTERED OFFICE 1 RULE 2 OBJECTS 2 RULE 3 MEMBERSHIP 3 RULE 4 MEMBERSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS and BENEFITS 7 RULE 5 OBLIGATIONS OF MEMBERS 10 RULE 6 LAY OFFICE 11 RULE 7 INDUSTRIAL/OCCUPATIONAL/PROFESSIONAL SECTORS 13 RULE 8 REGIONS 16 RULE 9 YOUNG MEMBERS 18 RULE 10 MEMBERS IN RETIREMENT 20 RULE 11 EQUALITIES 22 RULE 12 POLICY CONFERENCE 24 RULE 13 RULES AMENDMENT 27 RULE 14 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL 29 RULE 15 GENERAL SECRETARY 35 RULE 16 ELECTION OF EXECUTIVE COUNCIL MEMBERS AND THE GENERAL SECRETARY 36 RULE 17 BRANCHES 42 RULE 18 WORKPLACE REPRESENTATION 46 RULE 19 FUNDS 48 RULE 20 ASSETS AND TRUSTEE PROVISION 51 RULE 21 EXPENSES 53 RULE 22 POLITICAL ORGANISATION – THE LABOUR PARTY 54 RULE 23 POLITICAL FUND 56 RULE 24 IRELAND 68 RULE 25 REPUBLIC OF IRELAND – STRIKES AND OTHER INDUSTRIAL ACTION 71 RULE 26 ISLE OF MAN 73 RULE 27 MEMBERSHIP DISCIPLINE 74 RULE 28 COMMUNITY/STUDENT MEMBERS 78 RULE 29 SCOTLAND 79 RULE 30 GIBRALTAR 81 RULE 31 OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS 82 RULE 32 VOLUNTARY DISSOLUTION 83 RULE 33 EXERCISE OF UNION POWERS IN THE PENSION SCHEMES 84 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL GUIDANCE – NOTICE TO MEMBERS 85 APPENDIX TO RULE BOOK – LIST OF INDUSTRIAL SECTORS 86 UNITE RULE BOOK RULE 1 TITLE AND REGISTERED OFFICE 1.1 The Union formed under these rules (hereinafter called the Union) shall be known by the title of “Unite the Union”. -

2020/2021 the Trade Union (Facility Time Publication Requirements)

Trade Union Facility Time – 2020/2021 The Trade Union (Facility Time Publication Requirements) Regulations 2017 came into force on the 1st April 2017. These regulations place a legislative requirement on relevant public sector employers, including local authorities, to collate and publish, on an annual basis, a range of data on the amount and cost of facility time within their organisation. This note includes data required under these Regulations and data required under the Department for Communities and Local Government Transparency Code which took effect on 2nd February 2015. The Regulations require data to be published by function. This detail is set out below. Central Function employees are defined as employees other than those employed in the Education Function of the Council. Education Function employees are defined as persons employed by virtue of section 35(2) of the Education Act 2002 (staffing of community, voluntary controlled, community special and maintained nursery schools). The total cost of trade union facility time across both Central and Education functions for 2020/2021 was £64,903 which represents 0.04% of the authority’s total pay bill. Costs can vary on an annual basis as they are based on the actual salary of the individual representatives. Relevant union officials spent no paid time on trade union activities. 1. Central Function employees 2020/2021 In accordance with the national terms and conditions, the Council recognises the following trade unions for collective bargaining purposes in the Central Function: UNISON GMB UNITE Percentage of time spent No. of FTE on facility time 2018/19: representatives Less than 1% 8 7.43 1- 50% 3 2.28 51 - 99% 0 0.00 100% 2 1.81 Total 13* 11.52* * NB this is the total number and includes new representatives and any ceasing to be representatives during the year There were 13 (11.52 FTE) employees who were trade union representatives employed in the Central Function. -

Schools Told to 'Get Their Act Together'

the million-pound not-so-free schools: book review: bailouts for the true cost of interrogating failing schools gove’s project school training page 3 page 11 page 20 SCHOOLSWEEK.CO.UK FRIDAY, JANUARY 26, 2018 | EDITION 127 PORTER: WHY TEACHERS SHOULD SWAP THEIR CLASSROOMS FOR CELLS PROFILE P16-17 SCHOOLS TOLD TO ‘GET THEIR ACT TOGETHER’ Trusts failing to comply with new Baker Clause requirement PICKING APART Leaders argue there’s been little promotion of new law 2017 GCSE EXAM ALIX ROBERTSON DATA PAGES 3,6-7 @ALIXROBERTSON4 Investigates Page 5 HAVE YOU BOOKED YOUR TICKETS TO THE FESTIVAL OF EDUCATION YET? 21-22 JUNE 2018 BROUGHT TO YOU BY SAVE 20% ON TICKETS BY BOOKING BEFORE THE END OF JAN #EDUCATIONFEST | VISIT EDUCATIONFEST.CO.UK TO BOOK NOW 2 @SCHOOLSWEEK SCHOOLS WEEK FRIDAY, JAN 26, 2018 Edition 127 MEET THE NEWS TEAM schoolsweek.co.uk Shane Laura Experts Mann McInerney MANAGING EDITOR CONTRIBUTING EDITOR (INTERIM) @SHANERMANN @MISS_MCINERNEY TOM [email protected] [email protected] Please inform the Schools Week editor of any errors or issues of concern regarding this publication. RICHMOND Cath Freddie RSC’S OWN SCHOOL Murray Whittaker Page 18 FEATURES EDITOR CHIEF REPORTER GETS AN ‘INADEQUATE‘ @CATHMURRAY_ @FCDWHITTAKER Page 8 [email protected] [email protected] TOM PERRY Tom Alix Mendelsohn Robertson SUB EDITOR SENIOR REPORTER Page 18 @TOM_MENDELSOHN @ALIXROBERTSON4 [email protected] [email protected] THE DIGITAL DEGRADING OF PISA JAN Jess Pippa TESTS Staufenberg