Authorised Report of the Educational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

Download Issue 27 As

Policy & Practice A Development Education Review ISSN: 1748-135X Editor: Stephen McCloskey "The views expressed herein are those of individual authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of Irish Aid." © Centre for Global Education 2018 The Centre for Global Education is accepted as a charity by Inland Revenue under reference number XR73713 and is a Company Limited by Guarantee Number 25290 Contents Editorial Rethinking Critical Approaches to Global and Development Education Sharon Stein 1 Focus Critical History Matters: Understanding Development Education in Ireland Today through the Lens of the Past Eilish Dillon 14 Illuminating the Exploration of Conflict through the Lens of Global Citizenship Education Benjamin Mallon 37 Justice Dialogue for Grassroots Transition Eilish Rooney 70 Perspectives Supporting Schools to Teach about Refugees and Asylum-Seekers Liz Hibberd 94 Empowering more Proactive Citizens through Development Education: The Results of Three Learning Practices Developed in Higher Education Sandra Saúde, Ana Paula Zarcos & Albertina Raposo 109 Nailing our Development Education Flag to the Mast and Flying it High Gertrude Cotter 127 Global Education Can Foster the Vision and Ethos of Catholic Secondary Schools in Ireland Anne Payne 142 Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review i |P a g e Joining the Dots: Connecting Change, Post-Primary Development Education, Initial Teacher Education and an Inter-Disciplinary Cross-Curricular Context Nigel Quirke-Bolt and Gerry Jeffers 163 Viewpoint The Communist -

UCLA Historical Journal

Issue of British Recognition of the Confederate States of America 1 The Roebuck Motion and the Issue of British Recognition of the Confederate States of America Lindsay Frederick Braun ^^7 j^ \ ith the secession of the southern states from the Union and the i U I outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, British poHcymak- \^\^ ers and financiers had to contend with the novel diplomatic and economic difficulties of relations with two Americas locked in battle. Faced with an uncertain contest abroad and divided affinities at home, the govern- ment of Lord Palmerston chose to steer a middle course of neutrality. This did not, however, prevent advocates and detractors of both sides from orga- nizing opinion and advancing agendas across the country and even into Parliament. Debate on the situation within the warring states and sugges- tions that Britain might do weU to extend formal diplomatic recognition to the Confederate States of America as a sovereign nation, or to intervene in the conflict, appeared regularly in Parliament during the course of the war. The ill-fated Parliamentary motion towards recognition introduced in sum- mer of 1863 by John Arthur Roebuck, Member of Parliament for Sheffield, was the last of the serious attempts to secure recognition. It was, perhaps, the most telling effort of the entire war period in terms of the European diplo- matic landscape and Europe's relations to events in North America. Between the inception of Roebuck's motion in May 1863 and its with- drawal on 13 July 1863, its sponsor engaged in amateur diplomacy with the French, serious breaches of protocol, and eventually witnessed not only the obloquy of pro-Union and anti-interventionist speakers but also the desertion of other pro-Confederate members of Parliament. -

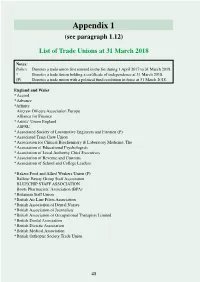

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

Network Preferences and the Growth of the British Cotton Textile Industry, C.1780-1914

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Network preferences and the growth of the British cotton textile industry, c.1780-1914 Steven Toms University of Leeds 6 July 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/80058/ MPRA Paper No. 80058, posted 8 July 2017 14:38 UTC Network preferences and the growth of the British cotton textile industry, c.1780-1914 By Steven Toms (University of Leeds) Preliminary draft, for presentation at Association of Business Historians Conference, Glasgow, June 2017. Keywords: Business networks, British cotton textile industry, innovation, finance, regions, entrepreneurship, mergers. JEL: L14, L26, O33, N24, N83 Correspondence details: Steven Toms Professor of Accounting, Leeds University Business School Room 2.09, Maurice Keyworth Building University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT Tel: 44(113)-3434456 Email: [email protected] Word count: c.11,000 Abstract The paper considers the dual aspect of social networks in terms of 1) product innovators and developers and 2) the providers of finance. The growth of networks can be explained as a function of incumbents and entrants’ preferences to link with specific nodes defined according to the underlying duality. Such preferences can be used to explain network evolution and growth dynamics in the cotton textile industry, from being the first sector to develop in the industrial revolution through to its maturity. The network preference approach potentially explains several features of the long run industry life cycle: 1. The early combination of innovators with access to extensive credit networks, protected by entry barriers determined by pre-existing network structures, leading to lower capital costs for incumbents and rapid productivity growth, c.1780-1830. -

The London Gazette, November 20, 1868. 5997

THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 20, 1868. 5997 Borough of Preston. Borough of Newcastk-under-Lyme. Edward Hermon, of Winchley-square, in the said Edmund Buckley, Esq. borough, Esq. William Shepherd Allen, Esq. Sir Thomas George . Jenner Hesketh, of Rufford Ci^y'of London. Hall, in Rufford, Lancashire, Bart. The Right Honourable George Joachim Goschen, Borough of Boston. ( Robert Wigram Crawford, John Wingfield Malcolm, of Great Stanhope- William. Lawrence, street, London, Esq. Charles Bell, Esqrs. Thomas Collins the younger, of Knaresbbrough, in the West Riding of York, Esq. City^qf Exeter. John Duke Coleridge, Esq., Q.C. Borough of Cambridge. Edgar Alfred Bowring, Esq., C.B. Robert Richard Torrens, William Fowler, Es>qrs. Borough of Bodmin. The Honourable Edward Frederick Leveson Borough'of Leicester. Gower, of Chiswick House, Middlesex, Esq. Peter Alfred Taylor, of Aubrey House, Netting Bupghs ofFortrose, Inverness, Nairn, and Forres. Hill, Middlesex,'Esq. John Dove Harris, of Katcliffe Hall, in the county Eneas William Mackintosh, of Raigmore, in the of Leicester, Esq. county of Inverness, Esq. Borough of Rochdale. Borough of Wednesbury. Thomas Bayley Potter, of Buile Hill, Pendleton, Alexander Brogden, Esq. Lancashire. City of Winchester. County of Westmorland. ^ William Barrow Simonds, Esq. The Right Honourable Thomas Taylour (com- John Bonham Carter, Esq. monly called Earl of Bective), of Virginia Lodge, Cavan, Ireland. Borough of Lymington. William Lowther, of Lowther Castle, in the.said county, Esq. - George Charles Gordon Lennox (commonly called Lord George Charles Gordon Lennox). Borough of JVestbury. Borough of Tynemouth. John Lewis Phipps, of Westbury, Esq. Thomas Eustace Smith, Esq. Borough of Chatham. Arthur John Otway, of Harley-street, London, Borough of Ludlow. -

The History of Parliament Trust Review of Activities, 2017-18

The History of Parliament Trust Oral History Project interviewees, clockwise from top: Baroness Helene Hayman, Baroness Ann Taylor, Jackie Ballard, Baroness Janet Fookes. All portraits by Barbara Luckhurst, www.barbaraluckhurstphotography.com © Barabara Luckhurst/History of Parliament Trust Review of Activities, 2017-18 Objectives and activities of the History of Parliament Trust The History of Parliament is a major academic project to create a scholarly reference work describing the members, constituencies and activities of the Parliament of England and the United Kingdom. The volumes either published or in preparation cover the House of Commons from 1386 to 1868 and the House of Lords from 1603 to 1832. They are widely regarded as an unparalleled source for British political, social and local history. The volumes consist of detailed studies of elections and electoral politics in each constituency, and of closely researched accounts of the lives of everyone who was elected to Parliament in the period, together with surveys drawing out the themes and discoveries of the research and adding information on the operation of Parliament as an institution. The History has published 22,136 biographies and 2,831 constituency surveys in twelve sets of volumes (46 volumes in all), containing over 25 million words. They deal with 1386-1421, 1509-1558, 1558-1603, 1604-29, 1660-1690, 1690-1715, 1715-1754, 1754- 1790, 1790-1820 and 1820-32. All of these articles, except those on the House of Lords 1660-1715, are now available on www.historyofparliamentonline.org . The History’s staff of professional historians is currently researching the House of Commons in the periods 1422-1504, 1640-1660, and 1832-1868, and the House of Lords in the periods 1603-60 and 1660-1832. -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland 2019-2020

2019-2020 Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland (Covering Period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020). 10-16 Gordon Street Process Colour C: 60 M: 100 Y: 0 Belfast BT1 2LG K: 40 Tel: 028 9023 7773 Pantone Colour 260 Process Colour C: 21 Email: [email protected] M: 26 Y: 61 K: 0 Web: www.nicertoffice.org.uk Pantone Colour 111 TYPEFACE : HELVETICA NEUE First published February 2021 CERTIFICATION OFFICER FOR NORTHERN IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Laid before the Northern Ireland Assembly under paragraph 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 by the Department for the Economy Mr Mike Brennan Permanent Secretary Department for the Economy Netherleigh House Massey Avenue BELFAST BT4 2JP I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 2 Mrs Marie Mallon Chair Labour Relations Agency 2-16 Gordon Street BELFAST BT1 2LG I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 3 CONTENTS Review of the year A summary from the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland . -

Directory. Manchester

DIRECTORY. PUBLIC BUILDINGS, &c. MANCHESTER.. Educational, &;e.,:Institations-conlill•ud. S"cretary, John DuOirld, E·se& chaq ben, 8 tir J<'X 1t Mllster, Jam~ .M'Cormick Ma•rou,Mrl!l ~·Connklr. lJWJ:NS COLLEGE-conlit~uec!. A •sistant 1\latroo, 1\1 i.s Swallo..- I!IUlOUl" l!lli:SSIOll'. [x.n. :r." ,!'I Music 1\l:rurtu, A rthur H •. gue PtUCTIC.lL PHYsiOLOGY AND HuToLOGT, Professor Arthnr G..~mgee, Schooln,as~r - K111rry OIIATKTincs, Pn.fessor John Thorburn, JI.D. J ' --- MATJ!:BI.I. MJtDIC.I. AND THEB.I.PEUTIC!!, Alexand.. r Somer•, II.B.c.s MANCHESTErt SCHOOLS FOF.. 'fH!. DEAF AND DUMB, UaoJrl J otm Leech, II,II. x.a.c.P. (London) OLD 'I IU. noan. Mt:DIUL J[rlli8PRVD&JICE .&ND PUBLIC H&.\LTD, Arthur Ran!om.,, Offic~!l 100 Kini•trrrt II.D. n . .&. (Cantllb.) . Patron, The Enrl of Derby ' PuCTIC4L 1\loRBID S:tsTOLOGY, Jnhus Dre•cbfeld, x.D. M.R.c.r. Patroness, The Counlesa of Derbyl 0 t'l'H .. LIJ(OLOG y. IJa nd Lutle, II.D. - l'resiclent, n. J. Le i•poc: P&&CTit'.l.~ CHI!IIIiTKY, P~?lesaor Henry E. Roscoe, P'. ···•· Tretuure•·, Oliver Hey wood llousr. I rnfeuor W. C. \\ilhawron,JI',ll.a. Hon.f>h)sieian, l\l. A. Eason Wilkioson DitllUliiSfii.\TOII. AND AssiSrAXT LKCTUKEH IN A:v.&.TOMY, Alfred H. Hon. Surgeon, Arlhur E. Sulr.litle Youn~, lLB . [P• ie•lley Hon. IJ.,ntisl, ltobert ll• oo"house DII:MO~•TilA.TOB AND '1\.~sr&T.A.l'OT LECTUKitK IN' PlfY!IIOLO~<Y, John Secretary, Jo,.,ph ::..unt, 100 Kini' atreet REGI&Til.&K, J. -

Give Us What We Deserve Taking to the Streets for SEND Funding

Willow’s Windrush nightmare Families at breaking point Windy City victories TA sacked due to hostile The impact of knife crime on Chicago teachers on the gains environment. See page 19. our communities. See page 26. of recent strikes. See page 37. July/ August 2019 Your magazine from the National Education Union Give us what we deserve Taking to the streets for SEND funding. See page 7 END OF TERM PREVIEWS FOR SCHOOLS TO ARRANGE A SPECIAL END OF TERM PREVIEW SCREENING* CONTACT [email protected] WITH AND EMILIA SEBASTIAN NICK CRAIG KATE RUPERT ALEX LEE WARWICK SANJEEV ALEXANDER CHRIS DEREK KIM JONES CROFT FROST ROBERTS NASH GRAVES MACQUEEN MACK DAVIS BHASKAR ARMSTRONG ADDISON JACOBI CATTRALL ARE YOUR STUDENTS #TEAMROMAN OR #TEAMCELT? REGISTER FOR A FUN & FREE LEARNING RESOURCE FROM INTO FILM AT WWW.INTOFILM.ORG/HORRIBLE-HISTORIES IN CINEMAS JULY 26 *PREVIEW SCREENING OFFER AVAILABLE FROM MONDAY JULY 8TH ONWARDS. HORRIBLEHISTORIES.MOVIE HORRIBLEHISTORIESTHEMOVIE Educate July/August 2019 Welcome Protestors at the SEND National Crisis demonstration. Photo: Rehan Jamil Willow’s Windrush nightmare Families at breaking point Windy City victories AS Educate goes to press, members of the Conservative Party are still deciding TA sacked due to hostile The impact of knife crime on Chicago teachers on the gains environment. See page 19. our communities. See page 26. of recent strikes. See page 37. who will become the country’s next Prime Minister. July/ August 2019 The fact that candidates in the Tory leadership election have raised the issue of school funding is testament to all the hard work of campaigners to get Your magazine from the National Education Union this issue on the political agenda. -

Our Hero Child Poverty and Marcus Rashford’S Fight for Free Holiday School Meals

Testing times Defend disabled members End period poverty Demanding school safety Ensuring protection for Free sanitary products during Covid-19. See page 6. at-risk educators. See page 22. in schools. See page 26. November/ December 2020 Your magazine from the National Education Union Our hero Child poverty and Marcus Rashford’s fight for free holiday school meals TUC best membership communication print journal 2019 Meeting your School’s Literacy Needs with Expert Training from CLPE Deepen your subject knowledge with CLPE’s professional courses The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) is an independent UK charity dedicated to raising the literacy achievement of children by putting quality literature at the heart of all learning. 100% 100% 99% Inspires the teacher. of people attending of people attending of people attending Inspires a class. The best our day courses our long courses our day courses would recommend rated the training rated their course course I’ve been on. it to someone else as eff ective as eff ective TEACHER ON CLPE TRAINING, 2019 NEW Online Learning from CLPE Our expert teaching team have developed a programme of online learning to provide extra support for your literacy curriculum. The programme will provide staff with evidence based professional development drawing on learning from CLPE’s research and face to face teaching programmes including: • The CLPE Approach to teaching literacy: Using high quality texts at the heart of the curriculum • CLPE Research and Subject Knowledge Series: Planning eff ective provision to ensure progress in reading and writing • Power of Reading Training Online: Developing a broad, rich book based English curriculum across your school This programme of learning will give primary teachers the opportunity to explore CLPE’s high-impact professional development online. -

The Anglican Assertion in Lancashire: the Role of the Commissioners' Churches in Three Lancashire Townships, 1818-1856 by Will

The Anglican Assertion in Lancashire: The Role of The Commissioners’ Churches in Three Lancashire Townships, 1818-1856 by William Walker A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire. July 2018 i STUDENT DECLARATION FORM Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards I declare that while registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. ________________________________________________________________ Material submitted for another award I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work. _________________________________________________________________ Signature of Candidate _______________________________________ Type of Award Doctor of Philosophy School Humanities and Social Sciences ii ABSTRACT The years between 1818 and 1856 encompass the life of the Church Building Commission, one agency of a determined assertion by the Anglican Church. Under the Commissioners’ aegis 82 of the 612 new places of worship were planted in Lancashire. The intention is to analyse the rationale and impact of a remarkable church building project and its role in the Anglican initiative in the county. The thesis is the first detailed local study of the churches’ distinctive role, beyond the assessment of their artistic worth. M.H. Port in Six Hundred New Churches (2006) produced the definitive work on the architecture and central administration of “Waterloo Churches”.1 He had less to say on their social and religious importance. In order to explore the rationale, impact and role of the churches, I adopted a case study approach selecting three churches in south central Lancashire, one from each deanery of Manchester Diocese which was created out of Chester Diocese in 1847.