Personal and Political

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Alias Walter Lam Or Lam San Ping). A-5366278, Yokoya, Yoshi Or Sei Cho Or Shiqu Ono Or Yoshi Mori Or Toshi Toyoshima

B44 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—MAY 23, 1951 [65 STAT. A-3726892, Yau, Lam Chai or Walter Lum or Lum Chai You (alias Walter Lam or Lam San Ping). A-5366278, Yokoya, Yoshi or Sei Cho or Shiqu Ono or Yoshi Mori or Toshi Toyoshima. A-7203890, Young, Choy Shie or Choy Sie Young or Choy Yong. A-96:87179, Yuen, Wong or Wong Yun. A-1344004, Yunger, Anna Steibel or Anna Kirch (inaiden name). A-2383005, Zainudin, Yousuf or Esouf Jainodin or Eusoof Jainoo. A-5819992, Zamparo, Frank or Francesco Zamparo. A-5292396, Zanicos, Kyriakos. A-2795128, Zolas, Astghik formerly Boyadjian (nee Hatabian). A-7011519, Zolas, Edward. A-7011518, Zolas, Astghik Fimi. A-4043587, Zorrilla, Jesus Aparicio or Jesus Ziorilla or Zorrilla. A-7598245, Mora y Gonzales, Isidoro Felipe de. Agreed to May 23, 1951. May 23, 1951 [S. Con. Res. 10] DEPORTATION SUSPENSIONS Resolved hy the Senate (the House of Representatives concurrmgr), That the Congress favors the suspension of deportation in the case of each alien hereinafter named, in which case the Attorney General has suspended deportation for more than six months: A-2045097, Abalo, Gelestino or George Abalo or Celestine Aballe. A-5706398, Ackerman, 2Jelda (nee Schneider). A-4158878, Agaccio, Edmondo Giuseppe or Edmondo Joseph Agaccio or Joe Agaccio or Edmondo Ogaccio. A-5310181, Akiyama, Sumiyuki or Stanley Akiyama. A-7112346, Allen, Arthur Albert (alias Albert Allen). A-6719955, Almaz, Paul Salin. A-3311107, Alves, Jose Lino. A-4736061, Anagnostidis, Constantin Emanuel or Gustav or Con- stantin Emannel or Constantin Emanuel Efstratiadis or Lorenz Melerand or Milerand. A-744135, Angelaras, Dimetrios. -

Rhodiapolis Antik Kentindeki Tarihsel Depremlerin Izleri (Kumluca, Antalya)

65.Türkiye Jeoloji Kurultayı 2-6 Nisan/April 2012 65th Geological Congress of Turkey RHODIAPOLIS ANTİK KENTİNDEKİ TARİHSEL DEPREMLERİN İZLERİ (KUMLUCA, ANTALYA) Gülşen Akan1, Erkan Karaman2 , Onur Köse3 1 Maden İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü, Ankara 2 Akdeniz Üniversitesi, Mühendislik Fakültesi, Antalya 3 Yüzüncüyıl Üniversitesi, Mühendislik ve Mimarlık Fakültesi, Van ([email protected]) ÖZ Rhodiapolis antik kenti, Doğu Likya’nın önemli yerleşkelerinden biri olup, MÖ 8. yy’da kurulmuştur. Rhodiapolis antik kentinin yerleşim alanı, geniş ve verimli bir ova olan Kumluca- Finike Ovası’nın kuzeyindeki Mesozoyik yaşlı Alakırçay Formasyonu birimleri üzerinde yer alır. Rhodiapolis antik kentinin yer aldığı Kumluca-Finike bölgesi, Türkiye’nin sismik etkinliğin en fazla olduğu 1. derece deprem bölgesinde bulunmaktadır. Bu nedenle bölge ve antik kent çok sayıda tarihsel depremin yıkıcı etkisi altında kalmıştır. Rhodiapolis’teki büyük işçilikler ve ustalıklarla yapılmış sağlam yapıların bir çoğu depremlerin etkisiyle yerlerinden oynayarak deforme olmuş; bazıları ise belli doğrultularda (çoğun GGB’ya doğru) yıkılarak harabe haline dönüşmüştür. Antik kent içindeki yapı duvarlarında yıkılmalar ve kırılarak bölünmeler, aynı yönde düşmüş sütunlar, duvarlardaki yamulma ve çökmeler, taş duvar parçalarındaki dönmeler ve itilmeler, yapılarda sistematik çatlaklar ile enkaz altında kalmış olduğu düşünülen insan iskeletleri tespit edilmiştir. Jeolojik, arkeolojik ve tarihsel deprem kanıtları, Rhodiapolis antik kentinin bir çok depremden etkilenmiş olduğunu göstermektedir. -

South Asian Art a Resource for Classroom Teachers

South Asian Art A Resource for Classroom Teachers South Asian Art A Resource for Classroom Teachers Contents 2 Introduction 3 Acknowledgments 4 Map of South Asia 6 Religions of South Asia 8 Connections to Educational Standards Works of Art Hinduism 10 The Sun God (Surya, Sun God) 12 Dancing Ganesha 14 The Gods Sing and Dance for Shiva and Parvati 16 The Monkeys and Bears Build a Bridge to Lanka 18 Krishna Lifts Mount Govardhana Jainism 20 Harinegameshin Transfers Mahavira’s Embryo 22 Jina (Jain Savior-Saint) Seated in Meditation Islam 24 Qasam al-Abbas Arrives from Mecca and Crushes Tahmasp with a Mace 26 Prince Manohar Receives a Magic Ring from a Hermit Buddhism 28 Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion 30 Vajradhara (the source of all teachings on how to achieve enlightenment) CONTENTS Introduction The Philadelphia Museum of Art is home to one of the most important collections of South Asian and Himalayan art in the Western Hemisphere. The collection includes sculptures, paintings, textiles, architecture, and decorative arts. It spans over two thousand years and encompasses an area of the world that today includes multiple nations and nearly a third of the planet’s population. This vast region has produced thousands of civilizations, birthed major religious traditions, and provided fundamental innovations in the arts and sciences. This teaching resource highlights eleven works of art that reflect the diverse cultures and religions of South Asia and the extraordinary beauty and variety of artworks produced in the region over the centuries. We hope that you enjoy exploring these works of art with your students, looking closely together, and talking about responses to what you see. -

PART TWO Critical Studies –

PART TWO Critical Studies – David T. Runia - 9789004216853 Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/2021 02:06:05PM via free access David T. Runia - 9789004216853 Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/2021 02:06:05PM via free access . Monique Alexandre, ‘Du grec au latin: Les titres des œuvres de Philon d’Alexandrie,’ in S. Deléani and J.-C. Fredouille (edd.), Titres et articulations du texte dans les œuvres antiques: actes du Colloque International de Chantilly, – décembre , Collection des Études Augustiniennes (Paris ) –. This impressive piece of historical research is divided into three main parts. In a preliminary section Alexandre first gives a brief survey of the study of the transmission of the corpus Philonicum in modern scholarship and announces the theme of her article, namely to present some reflections on the Latin titles now in general use in Philonic scholarship. In the first part of the article she shows how the replacement of Greek titles by Latin ones is part of the humanist tradition, and is illustrated by the history of Philonic editions from Turnebus to Arnaldez– Pouilloux–Mondésert. She then goes on in the second part to examine the Latin tradition of Philo’s reception in antiquity (Jerome, Rufinus, the Old Latin translation) in order to see whether the titles transmitted by it were influential in determining the Latin titles used in the editions. This appears to have hardly been the case. In the third part the titles now in use are analysed. Most of them were invented by the humanists of the Renaissance and the succeeding period; only a few are the work of philologists of the th century. -

Anti-Missionaries Love the Pagan "Parallel" Argument

B.R. Burton "The first to plead his case seems just, until another comes and examines him." Proverbs 18:17 Anti-missionaries love the pagan "parallel" argument. Despite rebuttals to the concept, the lingering idea never seems to die. What's more astounding is that "anti-missionaries" do not apply the same rules to themselves, as they do others, which, in most cases, is not surprising at all. One of the most famous "parallels" is in the virginal conception and birth of the Messiah. What the "anti-missionaries" do not take into account, nor mention, is the pagan parallels in the Tanakh, and even more specifically the birth of Moshe himself! As this pagan document states, Sargon, the great king of Akkad, am I. Of my father I know only his name.... Otherwise I know nothing of him. My father's brother lived in the mountains. My mother was a priestess whom no man should have known. She brought me into the world secretly.... She took a basket of reeds, placed me inside it, covered it with pitch and placed me in the River Euphrates. And the river, without which the land cannot live, carried me through part of my future kingdom. The river did not rise over me, but carried me high and bore me along to Akki who fetched water to irrigate the fields. Akki made a gardener of me. In the garden that I cultivated, Inanna (the great goddess) saw me. She took me to Kish to the court of King Urzabala. There I called myself Sargon, that is, the rightful king.1 Stephen Van Eck notes the similarities of, "Being placed in a basket sealed with pitch and set adrift on a river is the story of Sargon of Akkad, the first regional conqueror, who had lived more than a thousand years before Moses. -

Early Byzantine Pottery from Limyra's West and East

ISSN 1301-2746 ADALYA 23 2020 ADALYA ADALYA 23 2020 23 2020 ISSN 1301-2746 ADALYA The Annual of the Koç University Suna & İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations (OFFPRINT) AThe AnnualD of theA Koç UniversityLY Suna A& İnan Kıraç Research Center for Mediterranean Civilizations (AKMED) Adalya, a peer reviewed publication, is indexed in the A&HCI (Arts & Humanities Citation Index) and CC/A&H (Current Contents / Arts & Humanities) Adalya is also indexed in the Social Sciences and Humanities Database of TÜBİTAK/ULAKBİM TR index and EBSCO. Mode of publication Worldwide periodical Publisher certificate number 18318 ISSN 1301-2746 Publisher management Koç University Rumelifeneri Yolu, 34450 Sarıyer / İstanbul Publisher Umran Savaş İnan, President, on behalf of Koç University Editor-in-chief Oğuz Tekin Editors Tarkan Kahya and Arif Yacı English copyediting Mark Wilson Editorial Advisory Board (Members serve for a period of five years) Prof. Dr. Mustafa Adak, Akdeniz University (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Engin Akyürek, Koç University (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Nicholas D. Cahill, University of Wisconsin-Madison (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Edhem Eldem, Boğaziçi University / Collège de France (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Mehmet Özdoğan, Emeritus, Istanbul University (2016-2020) Prof. Dr. C. Brian Rose, University of Pennsylvania (2018-2022) Prof. Dr. Charlotte Roueché, Emerita, King’s College London (2019-2023) Prof. Dr. Christof Schuler, DAI München (2017-2021) Prof. Dr. R. R. R. Smith, University of Oxford (2016-2020) © Koç University AKMED, 2020 Production Zero Production Ltd. Abdullah Sok. No. 17 Taksim 34433 İstanbul Tel: +90 (212) 244 75 21 • Fax: +90 (212) 244 32 09 [email protected]; www.zerobooksonline.com Printing Fotokitap Fotoğraf Ürünleri Paz. -

Greenwood-Cemetery-By-Name.Pdf

Greenwood Cemetary Printed on: Tuesday, September 01, 2015 Last Name First Name M.I. Age Purchased Died Buried Block# Lot # Part of Lot Comments Abels Rev. L. 3/30/1893 F 02 E 1/2 Abels Ursula 39 3/29/1893 GS #7 Abing Allen W-1 04 W 1/2 Abing Craig A 25 4/5/1993 4/8/1993 W-1 04 W 1/2 Abrams Minnie, Mrs. 77 3/13/1952 3/17/1952 D 15 In Fred Mackey Block Ackerman Etta 46 2/27/1918 J 07 In Nickolas Wunn Block Ackerman Nelson 9/23/1937 J 07 In Nickolas Wunn Block Adams Douglas M 4/26/1951 0 Infant 4/27/?? Adickes Lloyd F 44 5/25/1958 GS #2 Adickes Margaret M 94 8/10/2013 8/15/2013 U 05 E 1/2 Adicks Floyd 44 6/28/1958 U 05 E 1/2 In Mrs. Frank VanNatta Block Adkinson O. E 8/19/1924 H 01 In Elk Lodge Block Adrian Mark & Lori 6/5/2014 W-1 29 SE 1/4 Aiken Cora, Mrs. M 73 1/8/1953 1/11/1953 G 08 In J.L. Mitchell Block Aiken Frances 19 10/24/1901 GS #7 Aiken Francis 73 4/23/1911 4/25/1911 G 15 Aiken Leslie 80 4/1/1960 4/1/1960 4/3/1960 U-1 03 E 1/2 Aiken Orrin W 79 5/25/1955 5/28/1955 G 08 In J.L. Mitchell Block Aiken Sarah A 83 11/29/1960 11/29/1960 U-1 03 E 1/2 Aiken William 87 6/26/1918 GS #7 Aiken Wm. -

Group Study Guide for Born Divine

Group Study Guide for Born Divine Robert J. Miller Introduction The purpose of this Study Guide is to facilitate the group discussion of Born Divine in adult education and book club settings. It can also be adapted for college and seminary courses. The Study Guide consists of questions and discussion topics that lead readers to the important points of the book, section by section through each chapter. Working with the Study Guide will help you to follow the book’s train of thought, to examine the evidence and reasoning for its conclusions, and, most important, to make up your mind in dialogue with both the book and your discussion partners. (The Study Guide can be used by individuals, in which case you will, in effect, be having discussions with yourself.) The best way to use the Study Guide is for each member of a group to work with it as they do their own reading, answering the questions and thinking through the discussion points for themselves prior to meeting as a group. Careful preparation by individuals makes for more thoughtful and productive group discussions. Most of the items in the Study Guide come in the form of questions or discussion topics. The discussion topics invite you to discuss a specific point, sometimes by considering that point in the light of other information. The purpose of these discussion points is to direct your attention to information of special interest or to elements in the reading that contribute to your understanding of the big picture. Many of the questions quote or restate a key sentence, ask you what exactly the sentence means and whether you agree with it. -

Astronomy and the "Star of Bethlehem"

Astronomy and the "Star of Bethlehem" Geraid Larue Each Decerr ber in planetaria and observatories across the halting in the heavens.' nation the pt.blic is invited to view simulations of"the heavens The pre-A.D. dating for the nativity is based upon an error at the time of Christ's birth." In most, if not all, presentations in calendaration that goes back to Dionysius Exiguus, a attempts are made to explain what the wise men (magoi) who Roman monk who in 533 attempted to determine the year of observed the star (aster) at its helical rising ("in the east") may Jesus' birth. He made at least two mistakes. He omitted the have seen. Explanations include that postulated by Johannes year 0, so that in our calendar we move from 1 B.C. to A.D. 1, Kepler, the German astronomer who, in 1603, witnessed a and he miscalculated when Jesus was born. According to the triple conjunction, or crossing, or massing, of the planets and Gospel of Matthew, Jesus was born during the reign of King thought that this may have been the aster of the magoi. Kepler Herod. In the first century A.D., the Jewish historian Josephus also suggested that they may have witnessed a supernova, recorded that Herod died shortly after a lunar eclipse. One of which is the collapse a star resulting in the expulsion of much lunar eclipse took place on March 13, 4 B.C., and hence some of its mass in an extremely bright but short-lived light. would place Jesus' birth before 4 B.C. -

Thesis for the Degree Of

Reconfiguring the Universe: The Contest for Time and Space in the Roman Imperial Cults and 1 Peter Submitted by Wei Hsien Wan to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology and Religion February 2016 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ……………………………………………………………………………… Abstract Evaluations of the stance of 1 Peter toward the Roman Empire have for the most part concluded that its author adopted a submissive or conformist posture toward imperial authority and influence. Recently, however, David Horrell and Travis Williams have argued that the letter engages in a subtle, calculated (“polite”) form of resistance to Rome that has often gone undetected. Nevertheless, discussion of the matter has remained largely focused on the letter’s stance toward specific Roman institutions, such as the emperor, household structures, and the imperial cults. Taking the conversation beyond these confines, the present work examines 1 Peter’s critique of the Empire from a wider angle, looking instead to the letter’s ideology or worldview. Using James Scott’s work to think about ideological resistance against domination, I consider how the imperial cults of Anatolia and 1 Peter offered distinct constructions of time and space—that is, how they envisioned reality differently. -

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

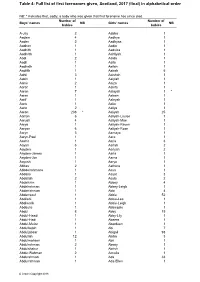

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) In

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2017 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A-Jay 2 Aabha 1 Aadam 4 Aadhya 1 Aaden 2 Aadhyaa 1 Aadhan 1 Aadia 1 Aadhith 1 Aadvika 1 Aadhrith 1 Aahliyah 1 Aadi 2 Aaida 1 Aadil 1 Aaila 1 Aadirath 1 Aailah 1 Aadrith 1 Aairah 5 Aahil 3 Aaishah 1 Aakin 1 Aaiylah 1 Aamir 2 Aaiza 1 Aaraf 1 Aakifa 1 Aaran 7 Aalayah 1 * Aarav 1 Aaleen 1 Aarif 1 Aaleyah 1 Aariv 1 Aalia 1 Aariz 2 Aaliya 1 Aaron 236 * Aaliyah 25 Aarron 6 Aaliyah-Louise 1 Aarush 4 Aaliyah-Mae 1 Aarya 1 Aaliyah-Raven 1 Aaryan 6 Aaliyah-Rose 1 Aaryn 3 Aamaya 1 Aaryn-Paul 1 Aara 1 Aashir 1 Aaria 3 Aayan 6 Aariah 2 Aayden 1 Aariyah 2 Aayden-James 1 Aarla 1 Aayden-Jon 1 Aarna 1 Aayush 1 Aarya 1 Abbas 2 Aathera 1 Abbdelrahmane 1 Aava 1 Abdalla 1 Aayat 3 Abdallah 2 Aayla 2 Abdelkrim 1 Abbey 4 Abdelrahman 1 Abbey-Leigh 1 Abderrahman 1 Abbi 4 Abderraouf 1 Abbie 52 Abdilahi 1 Abbie-Lee 1 Abdimalik 1 Abbie-Leigh 1 Abdoulie 1 Abbiegale 1 Abdul 8 Abby 19 Abdul-Haadi 1 Abby-Lily 1 Abdul-Hadi 1 Abeera 1 Abdul-Muizz 1 Aberdeen 1 Abdulfattah 1 Abi 7 Abduljabaar 1 Abigail 93 Abdullah 12 Abiha 3 Abdulmohsen 1 Abii 1 Abdulrahman 2 Abony 1 Abdulshakur 1 Abrish 1 Abdur-Rahman 2 Accalia 1 Abdurahman 1 Ada 33 Abdurrahman 1 Ada-Ellen 1 © Crown Copyright 2018 Table 4 (continued) NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB